Do Yolk and Grease Really Ruin Egg Whites for Beating?

Cooks are often told that even the tiniest bit of yolk or fat in egg whites will prevent them from whipping properly. Is it true?

When we published an article and recipe for a light and tender honey-almond cake in which we discussed techniques for beating egg whites we included tips like adding a touch of acid and beating the whites slowly. We also stressed the importance of keeping the whites free of yolk and any other fats.

It's a common piece of kitchen advice, one that we've given before. And, like us, many publications have made it sound very extreme: Get even a trace of yolk in those whites, and your ability to beat them into a foam is pretty much gone. Some people go so far as to have a separate mixing bowl and whisk just for egg whites, to prevent any contamination from fats.

But then, in the comments on our article, SE user Ananonnie said that the no-yolk rule is greatly exaggerated, posting a link to this article.

I don't do much baking, but I was interested in putting this to the test—it's such a common rule, striking fear into the hearts of beginner bakers. Wouldn't it be great if the risks weren't as significant as so often claimed?

Beating Basics

Let's look at what happens, in a nutshell (or should that be eggshell?), when we beat egg whites into foams. Egg whites themselves are about 90% water and 10% protein. If we try to beat pure water into a foam, it won't work: No matter how much force and agitation we apply, and no matter how many tiny little air bubbles we can create, the water will quickly settle back into a fully liquid state, and the air bubbles will float out.

But the proteins in egg whites change things. They start out as curled-up little balls, but as we beat the whites, the force we exert causes the proteins to stretch out. Once that happens, they begin to bond with each other. Meanwhile, all of the beating action is creating little air bubbles in the liquid. While bonding with each other, those stretched-out proteins begin to form a somewhat stable network around each tiny air bubble, and as that network becomes stronger and stronger, the whites get stiffer and stiffer. It's no longer easy for those air bubbles to escape, and the foam is born.

In theory, yolk and other fats can interfere with this process by bonding with the proteins (therefore preventing the proteins from bonding with each other), and by stealing spots around those air bubbles. This interference by fat can make it difficult for a stable enough protein network to form.

The question, though, is just how much fat it takes to mess things up. Even a trace amount, as cooking wisdom so often claims?

The Tests

To test it out, I started by carefully separating whites and yolks. I cracked each egg into a small bowl, and only after confirming that no visible yolk had leaked did I transfer it to the larger bowl of whites. Yolks, meanwhile, went in a separate bowl.

I carefully washed and dried both the stainless steel bowl and the whisk of a stand mixer. Then I decided on a timed sequence that I would use for every batch I was going to test: I would start the mixer out at low speed (#2 on the KitchenAid stand mixer I was using) for one minute, then increase the speed to medium-low (#4 on the mixer) for three minutes, and then finally increase the speed to just above medium (#6 on the mixer), at which point I would let it run as long as necessary to get very stiff whites.

There's no hard science for judging the stages of beaten whites: "Soft peaks" are generally defined as foamy whites capable of forming soft mounds that flop over; "stiff peaks" are whites that can stand up straight without flopping over; beyond that, you're usually getting into over-beaten territory, with the whites becoming grainy and weeping liquid. The reality is that these phases are not discrete points, but rather zones on a gradual continuum from unbeaten to over-beaten. In my tests, I stopped the machine from time to time (stopping my timer as well) to gauge the approximate stage of the whites during this process.

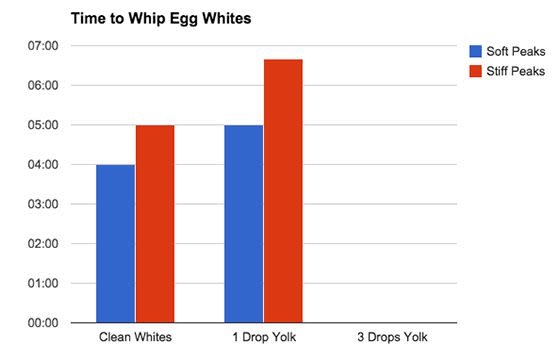

For my first batch, I wanted to establish a baseline of beating times for clean whites, so I measured out 100 grams of yolk-free egg white, which is roughly equal to the whites from three large eggs, and found that it took about four minutes to reach soft peaks and about five minutes to reach stiff peaks.

In my next batch, I added one drop of yolk to the same quantity of whites.

Without a pipette or some other more precise tool for measuring very small quantities of liquid, I had to settle for freeform drops of yolk. I therefore don't have an exact measurement for how much yolk I added. Still, extreme precision isn't necessarily so important here: Since no one adds yolk to their whites on purpose, and since there's no way beyond a visual assessment to measure yolk that's accidentally gotten into whites, knowing exact quantities doesn't really help in real-life situations. My main goal was to get a rough idea of whether whites can tolerate the presence of any yolk or not, and, if so, approximately how much.

In any case, with that single drop of yolk, the whites still managed to form both soft and stiff peaks, but it took longer: about five minutes for soft peaks, and six minutes 45 seconds for stiff peaks.

I let both the batch of very stiff clean egg whites and the batch with one drop of yolk sit for at least one hour, and, aside from both of them weeping liquid—the result of being whipped to the point of being over-beaten—both batches retained their shape the entire time without deflating.

It's possible that there was a subtle difference in the structure of the two foams due to the presence of the drop of yolk in one of them, but to the naked eye, it was invisible.

For my third batch, I added three drops of yolk to 100 grams of white, a fairly significant amount, and here things broke down: The whites were unable to whip up to even the soft-peak stage, even after seven minutes and 30 seconds of beating time.

I ran the test one more time, doubling the amount of whites to 200 grams (about six large eggs' worth), and saw the same trend: The presence of a single drop of yolk slowed the formation of foam, with the clean whites hitting soft peaks at four minutes 30 seconds and the ones with one drop of yolk reaching soft peaks at five minutes.

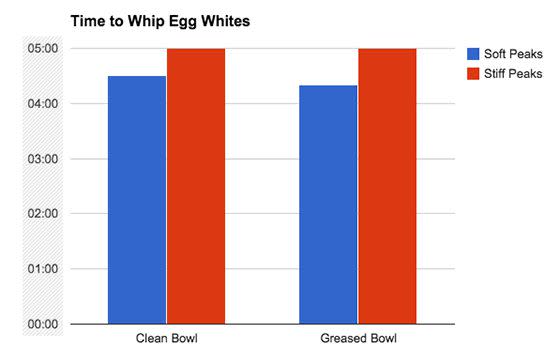

For a final test, I took a paper towel and soaked it with some vegetable oil, then rubbed a very thin sheen of that oil in the mixing bowl itself, to simulate a bowl that wasn't washed properly and still had traces of fat on it.

In this case, I saw no change in the whipping time compared to my batches in which everything was clean: The greased-bowl whites hit soft peaks at about four minutes 20 seconds and stiff peaks at about five minutes, compared to four minutes 30 seconds and five minutes, respectively, for the clean whites.

Conclusion

The advice to keep your whites clean and free of yolk or other fat is based on a truth: Fat can interfere with the beating of egg whites into a stable foam, and it does have the potential to completely ruin the batch. But it is not true that a trace or speck of fat is guaranteed to prevent whites from foaming up properly.

Based on these tests, a speck of yolk in a batch of egg whites is no reason to send them down the drain, as they will likely whip up just fine, albeit a little more slowly than totally clean ones. And trace amounts of fat, such as in a not-perfectly-clean bowl or on the whisk itself, do not present much of a risk at all. Given how quickly egg whites can be beaten into soft or stiff peaks, it seems worth at least trying out the tainted whites before giving up on them.

Do you want yolk or fat in your whites? No. But if you do get a tiny bit in? There's a good chance they'll turn out okay.

October 2014