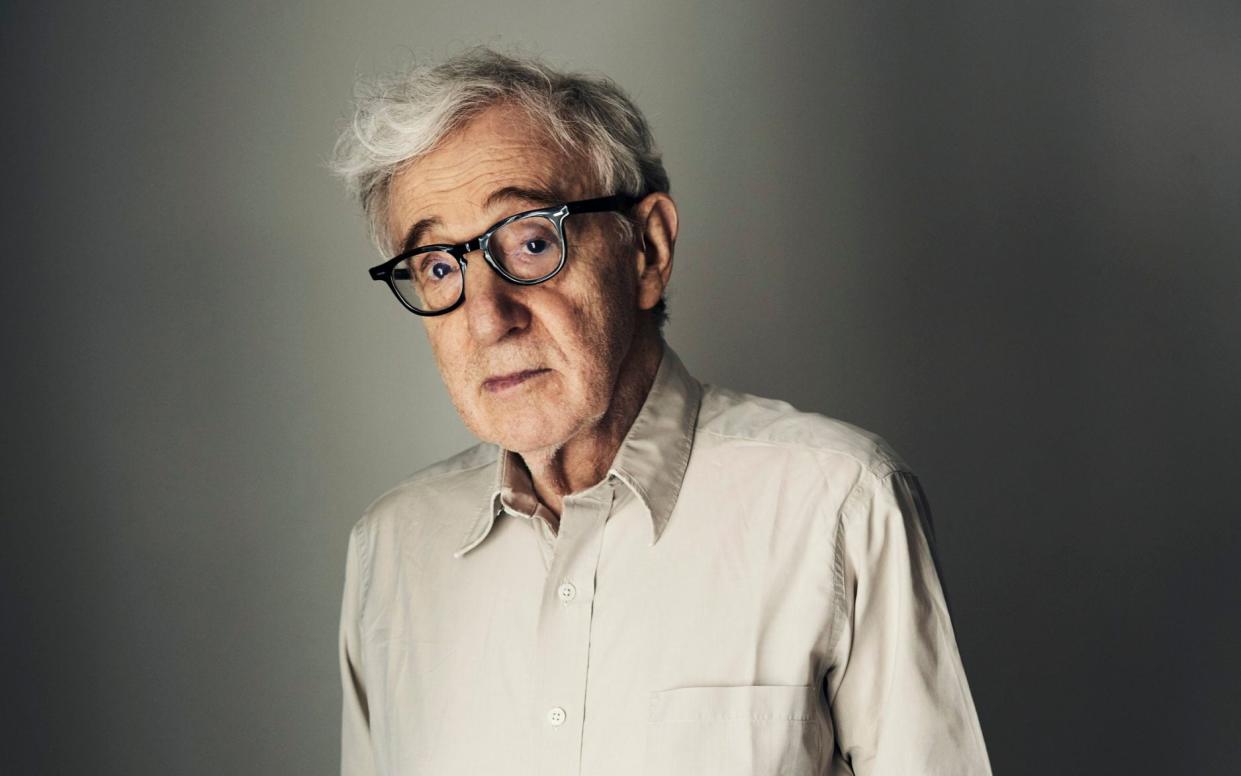

Woody Allen interview: ‘Ronan Farrow’s journalism is shoddy – I’m not sure his credibility will last’

“For my entire life my films have struggled commercially,” says Woody Allen. “And now we’ve finally found out that all it really required for one of them to do big business was, you know, a major catastrophe.”

The 84-year-old director is reflecting on the news that his rose-tinted romantic comedy A Rainy Day in New York has topped the global box-office chart during the coronavirus outbreak. The line is bad, but the voice at the end of it is unmistakable – the only one I’ve ever heard that can twinkle with despair. He says he’s hopeful this lucky streak will continue, and the release of his next coincides with nuclear war, or an asteroid hitting the Earth.

Allen’s productivity is legendary: these days, it may be the second best-known thing about him. (We’ll come to the first in a bit.) Since 1966, he’s averaged almost one film per year, and was supposed to be shooting his 50th this summer until the pandemic struck. His 49th, the Spain-set romance Rifkin’s Festival, was completed a few weeks before lockdown bit. He finished A Rainy Day in New York, his 48th, in 2018, but it’s only recently been taken down from the shelf. Why the delay? Again, we’ll get there.

Anyway, now the summer shoot’s off, and all there is for him to do is potter: watch the news in the mornings and a film in the evenings, practise the clarinet, and go for “brief, defensive walks” around the neighbourhood with Soon-Yi, his wife of 22 years. (The couple’s two adopted daughters, Bechet, 22, and Manzie, 20, are living with college friends.)

He’s also written a new play on the same Olympia portable typewriter he’s been using since he was 16 years old, crafting one-liners for Broadway columnists from his parents’ kitchen table in Brooklyn. But these days, his motivation is at an all-time-low ebb. “I’m used to finishing a script, carrying it out of the typewriter and going right into production,” he laments. “But now, all you can do is throw it in a drawer until life returns to the planet.”

The New York the world knows is in part an Allen creation. It’s the city of Annie Hall, Hannah and her Sisters and Radio Days; the natural habitat of the urbane, neurotic, sexually ambitious Jew in corduroy and tweed. But the toll the pandemic has taken on his home town has been “a complete curse out of science fiction; perhaps the worst thing I’ve ever witnessed”. He says the city feels even less like itself than in the grief-stricken aftermath of the 2001 terrorist attacks, and he couldn’t bring himself to make a movie about it in its current state. He lost a close friend to Covid last month, the banjo player Eddy Davis, who led the jazz band Allen has played with for some 35 years. Davis “succumbed very quickly” to complications from the virus in early April, “and we were naturally shocked and greatly saddened by it. By the human, personal loss and the musical loss too. It was a tragic thing.”

To the average onlooker, Allen does not appear to be a man with many longstanding allies left to lose. In 2014, while the director was being honoured (in absentia) at the Golden Globes, his estranged son Ronan Farrow, then embarking on a career as an investigative journalist, took to Twitter to call him a child molester. “Missed the Woody Allen tribute,” began Ronan’s tweet, which has since been deleted. “Did they put the part where a woman publicly confirmed he molested her at age seven before or after Annie Hall?”

The woman in question was Ronan’s sister Dylan, whom Allen was accused of sexually abusing in 1992 at the height of his bitter custody dispute with Mia Farrow, his partner of 12 years and the star of some of his best-regarded films. The claim was investigated at the time by the Child Sexual Abuse Clinic at Yale New Haven Hospital and the New York State Department of Social Services, who both independently concluded that Dylan had not been sexually abused. As such, no charges were ever brought against Allen.

But his subsequent loss of the custody trial left wisps of suspicion lingering over the case, and his relationship with the then-21-year-old Soon-Yi – Mia’s adopted daughter from her earlier marriage to André Previn – only thickened the fog. Allen has always maintained what the Yale investigators themselves hypothesised in 1992 and Dylan’s brother Moses, who was 14 at the time, described in a 2018 essay: that Mia had coached a vulnerable seven-year-old to recount a fictional incident which she eventually came to believe took place. Dylan’s response was unequivocal: “She has never coached me.”

But decades later, when the #MeToo movement had caught fire, a revised account of the assault from Dylan in an open letter seemed to many to fit all too well with the other bales of dirty show-business laundry that were being heaved into the light. The allegation is, of course, no more or less true today than it was in 1992. But Hollywood’s response to it has been drastically different.

In 2018, Amazon Studios terminated Allen’s four-film deal three films early, which led to a now-resolved £52 million lawsuit and the company’s offloading of A Rainy Day in New York to smaller distributors worldwide. (In the US, it still remains unclaimed.) And in March, Hachette dropped his forthcoming memoir Apropos of Nothing, following staff walkouts and a public dressing-down from Ronan, whose book about the Weinstein scandal had been published by another arm of the company. (Allen’s book was subsequently rushed into print by a smaller firm, Arcade.)

The intertwined downfall and rise of a father and son appeared to be the tale’s truly Freudian coup de grace. But now the rigour and accuracy of Farrow’s reporting has been called into question by the New York Times and others, what does Allen make of his offspring’s ascent?

“Up until a couple of days ago I would have said ‘Gee, this is great, he’s done some good investigative journalism and more power to him, I wish him all the success in the world,” he says. “But now it’s come out that his journalism has not been so ethical or honest. Now, I found him to not be an honest journalist in relation to me at all, but I write that off because, you know, I understand he’s loyal to his mother. But now people are beginning to realise that it isn’t just in relation to me that his journalism has been kind of shoddy, and I’m not so sure that his credibility is going to last.”

Dispassionate doesn’t quite capture Allen’s tone as he talks about this. Extreme nonchalance is more like it. The emotional drawbridge was clearly hoisted up years ago, and though he happily and fully answers any question you put to him, it still feels as if you’re standing on the far side of the moat, throwing stones at the portcullis. The same equanimity comes into play when he talks about the actors who have publicly disowned him since the revival of Dylan’s accusation, including Colin Firth, Greta Gerwig, Ellen Page, Kate Winslet (more opaquely), and now Timothée Chalamet, A Rainy Day in New York’s leading man.

Meanwhile, Scarlett Johansson, Javier Bardem, Diane Keaton and Jeff Goldblum are among those to have spoken out in his defence, while last year, Michael Caine walked back his earlier disavowal, describing the allegation as “hearsay”.

In A Rainy Day in New York, Chalamet plays the now-familiar figure of the Allen stand-in – here a bookish gadabout called Gatsby Welles, whose romantic trip to Manhattan with his girlfriend Ashleigh (Elle Fanning) goes whimsically awry. Like many of Allen’s late-late films – and this is a good one – much of it feels beamed in from 50 years ago. Though it’s set in the present, Chalamet croons a Chet Baker number at the piano, and cracks wise about Lerner and Loewe’s Gigi. That it works as well as it does comes down hugely to Allen’s three vivacious young leads: Chalamet, Fanning, and Selena Gomez, who plays a young actress on the rise.

Both Fanning and Gomez have artfully deflected attempts to extract apologies for appearing in the film. But in a January 2018 Instagram post, Chalamet said he’d come to realise “that a good role isn’t the only criteria for accepting a job” and he would donate his salary to charity, adding that he didn’t “want to profit from [his] work on the film”.

In his book, Allen explains away Chalamet’s mea culpa as pre-Oscar nerves. (In the end Chalamet was Oscar-nominated, but lost to Gary Oldman.) “He made a mistake,” Allen says. “He was nervous about wanting to win it, and it turned out to be a poor decision because he didn’t win it... Perhaps when he’s older he won’t feel that way. I can only say that I had a wonderful time working with him, and I liked him, and I was surprised when he denounced the project – well, not the project, but me. I found it hard to believe that he felt that way, having worked with him closely for a couple of months.”

Last year, it was widely speculated that A Rainy Day In New York might never see the light of day anywhere, and could even be the last film Allen would make, so decisively had the mood seemed to shift against him. In his memoir, he describes the subsequent struggle to cast Rifkin’s Festival, noting the “paucity of actors willing to throw their lot in with a toxic personality.” Yet in the end, he secured an international cast including Christoph Waltz, Gina Gershon and Wallace Shawn, while financial backing came from Spain’s Mediapro Group.

Did he ever worry that he was finished? Today he says not; he’s finding the allegation “hasn’t resonated in any real practical or detailed way” away from the media churn. “I still make my movies, I still get my plays produced. My following has never been huge but it’s always been loyal, and has remained for the most part intact. Every now and then there’s an annoying little glitch when an actor says they’re not going to work with you, but I just get a different actor. Not the end of the world.”

Again, the drawbridge holds firm. Yet in his recent films, you can hear the odd telltale creak, from the righteous murder of a corrupt family court judge in Irrational Man to the young son in Wonder Wheel who responds to a troubled home life by trying to burn everything down.

Allen’s emotional life is clearly tightly compartmentalised. His memoir describes Mia as a “wonderful” actress who “never got her due” one moment, then an “unhinged and dangerous woman” the next. “I have great criticisms and quarrels with Mia in my story, but certainly I can appreciate her acting very much,” he says. “I have no problem separating the art from the artist whatsoever. I can see Triumph of the Will and acknowledge that Leni Riefenstahl” – Hitler’s favourite filmmaker – “was a magnificent director, even though what she stood for was pretty awful.”

Given Allen has himself been the subject of endless art-versus-artist debates, this remark could come across as blatant trolling. Having read more about the case in the last few years than is probably healthy, I think it’s just a tone-deaf remark from a man now prone to them after having talked himself inside out on an extremely painful subject.

After the custody hearing, he says he found himself waiting for a reappraisal that never came: “the moment the public thought ‘It’s just so illogical that this guy would do this, he has no record of it, he’s been a solid citizen,’ and I’d be given the benefit of the doubt.” He’s stopped waiting now, though. “I think it will be this way for the rest of my life, and probably the rest of my death too,” he says. He speaks like a man who’s at peace with his sentence.

A Rainy Day in New York is available on Premium On Demand platforms from Friday June 5