Why Church Attendance Is More Important Than Ever

We live in an increasingly anxious, fractured, distracted, disembodied, and anti-institutional age. And as we wrote in The Great Dechurching, we also live in an age experiencing the largest and fastest religious shift in U.S. history: 40 million adult Americans have left churches over the last 25 years. That shift is larger—and running in the opposite direction—than what happened during the First Great Awakening, Second Great Awakening, and the Billy Graham Crusades combined. And it is happening 25 percent faster than any other 25-year period in U.S. history.

In an excellent recent article for The Atlantic, Derek Thompson highlights many features of these unfolding cultural and sociological dynamics:

And America didn’t simply lose its religion without finding a communal replacement. Just as America’s churches were depopulated, Americans developed a new relationship with a technology that, in many ways, is the diabolical opposite of a religious ritual: the smartphone. As the social psychologist Jonathan Haidt writes in his new book, The Anxious Generation, to stare into a piece of glass in our hands is to be removed from our bodies, to float placelessly in a content cosmos, to skim our attention from one piece of ephemera to the next. The internet is timeless in the best and worst of ways—an everything store with no opening or closing times. “In the virtual world, there is no daily, weekly, or annual calendar that structures when people can and cannot do things,” Haidt writes. In other words, digital life is disembodied, asynchronous, shallow, and solitary.

But Thompson, a self-described agnostic, goes on to point out that, “religious ritual is typically embodied, synchronous, deep, and collective.” Given our backgrounds, it’s no surprise that we believe church attendance can and should push against the anxious, fractured, distracted, disembodied, and anti-institutional age the West finds itself in. Data shows that church attendance matters now more than ever both for those who believe and for those who don’t believe the basic tenets of Christianity.

Why church attendance matters even for non-believers.

There’s a strong empirical argument that people who don’t believe in the basic tenets of any faith group should still make it a habit to attend services at a house of worship. In a recent study published in the Sociology of Religion, scholars examined whether church attendance was associated with improved mental or physical health during the COVID-19 pandemic. The data points to a clear conclusion: The people in the sample who reported better overall health outcomes were those who attended religious services in person at least once a week. Attending religious services online, meanwhile, brought no measurable health benefit.

That study isn’t the only one to find a positive relationship between religious attendance and mental health. Using data Pew collected during the earliest days of the COVID lockdowns, Ryan found that 28 percent of political liberals who never attended religious services had been diagnosed with a mental health condition. Among weekly attending liberals, that share was just 15 percent. Additionally, weekly attenders were much less likely to say they were feeling depressed, lonely, or anxious compared to those who attended church less than once a year.

Other work concludes that religious attendance may actually be the most positive aspect of the religious experience when it comes to the health of democracy as well. In the first paper he published in a scholarly journal, Ryan looked at religion’s effect on the concept of tolerance. Tolerance, simply put, is “putting up with those with whom we disagree.” It doesn’t mean one accepts or agrees with the other’s position, just that they should have the right to express their opinion. Ryan’s data indicated that those who believe in biblical literalism or those who identify as evangelicals are less politically tolerant. But those who attended religious services weekly expressed a higher level of tolerance. That’s likely because attending a house of worship regularly puts one in contact with a diversity of opinions and teaches individuals to still maintain friendships with people they disagree with. Recent work in economics found that while schools, neighborhoods, and workplaces have lots of economic homogeneity, being a member of a house of worship exposed individuals to people from different rungs of the economic ladder.

There’s also ample evidence that going to church on a regular basis provides the tools for individuals to more effectively engage in the political process. For instance, political scientists Paul Djupe and Chris Gilbert found that those who were more involved in religious life were more likely to develop certain civic skills, such as how to run a meeting or organize a fundraiser—tools that can come in handy when engaging with the democratic process. That development was more pronounced among people at the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum—which means churches are actually helping those with less education and income become more engaged and effective in the political process. Other empirical work has concluded that individuals who are more involved in their house of worship are also more inclined to engage in things like school board meetings, political protests, and working for a candidate or campaign. In essence, involvement with one part of civic life spills over into other parts of one’s community.

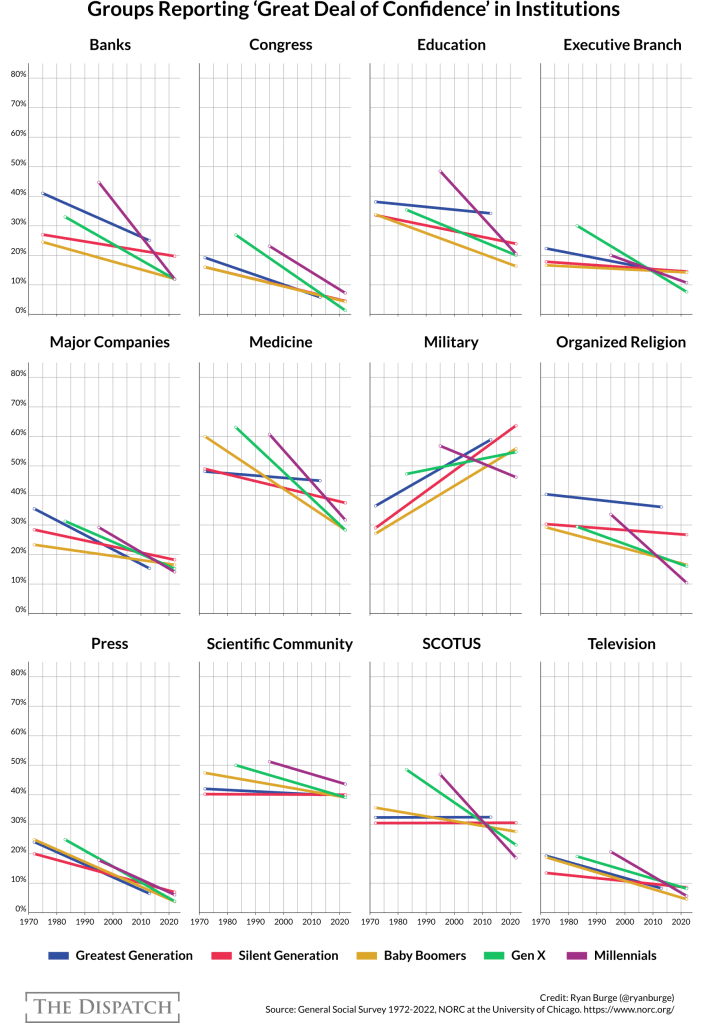

One aspect of the fractured nature of our current age that Thompson and others have written about is the current crisis of confidence in institutions:

In some ways, it is because of this crisis of confidence that institutions have never mattered more. This is doubly true for institutions that convene broad groups of people in real life. Of the 12 institutions in the graphic above, only education and organized religion match that description. It is important for houses of worship to be cognizant of these dynamics and work to create more vibrant communities.

Social scientists have long understood religion to be a multifaceted concept encompassing behavior (regular worship attendance), belonging (an individual identifying as a Protestant Christian or a Muslim, for instance), and belief (the theological aspect of the religious experience). The trends in the survey data reveal that those three aspects of religion are not declining at the same rate. While just 12 percent of people hold to an atheist or agnostic view of God, about 30 percent report that they have no religious affiliation. Yet, the remaining dimension—religious behavior—has fallen the fastest. Now, a majority of Americans report that they have not attended a religious service in the prior year.

Thus, the best parts of religion (regular attendance at a house of worship) have been left to decay, leaving us only with the most caustic and divisive dimension of the religious experience. This may be one of the primary reasons for the increasing distrust in American religion: The average American understands that it’s just one more way to divide people into subgroups. Social science provides us with ample evidence that going to church on a regular basis can bring with it a whole host of benefits—social, mental, physical, and relational. Unfortunately, it’s becoming harder and harder to make that argument as religion is reduced to another way to demonize and exclude the “other.” The end result is an unhealthy society and a weakened democracy.

Why church attendance matters for those who believe.

There is no shortage of valid critique of churches in America—both for their internal problems and how they address external challenges in wider society. If your media diet leans one direction, stories of racism, misogyny, clergy abuse, and political syncretism are ubiquitous. If your media diet leans the other direction, stories of secularism, progressivism, and the sexual revolution are ubiquitous. All of these issues are problems, and they have all resulted in a few million people leaving. Of course, churches would do well to avoid error in all sorts of directions and pursue truth, goodness, and beauty.

However, perhaps the most shocking revelation from our comprehensive quantitative study of dechurching was this: Roughly 30 million people (three quarters of people who have “dechurched” in the last 25 years) did so for primarily highly pragmatic reasons such as, “I moved,” “attendance was inconvenient,” or “divorce, marriage, or another family change.”

How is this working out for Americans? We have all read the stories—such as Thompson’s—looking at the rise in anxiety, depression, addiction, despair, and division. It seems obvious that many people today are pursuing unlivable and unsustainable habits and rhythms.

Even though Jonathan Haidt is an atheist and Derek Thompson is agnostic, they can both clearly see why the institution of the local church has never been more important. If they can see the extrinsic institutional, cultural, societal value, how much more ought religious adherents see the importance of their religious attendance and participation?

Ross Douthat was right when he quipped on X that, “People who 30 percent believe in God should 100 percent go to church, this should not even be a question.”

In an age when the swift court of public opinion shows no mercy, we find grace in Jesus’ atonement. In an age of performative self-righteousness, we find humility in our need for Jesus’ righteousness. In an age of internally manufactured identities, we find the importance of externally given identities. In an age of radical individualism, we find joy in serving others in community. In an age of anxiety, we relinquish control and cast our burdens on Jesus.