Ursula Andress versus rotting crabs: how Dr. No was saved from disaster

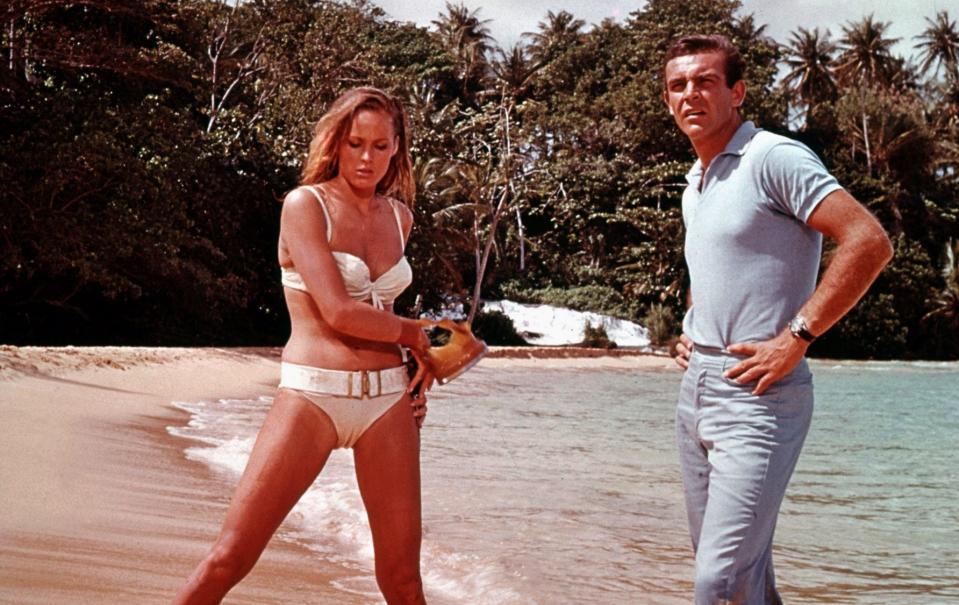

The king crabs lay dead and dying around Ursula Andress. Crustaceans the size of hubcaps had been employed to terrorise her, threaten to rip her skin to shreds and eat her alive.

Instead, they had arrived at the set of Dr. No packed in ice and partially frozen. Now most of them weren’t moving. Some gently decomposed. Editor Peter R Hunt looked on in despair as Andress attempted to look terrified of dozens of expiring crabs. “It was a disaster,” he said later.

The crabs’ welfare was the least of anyone’s worries. When filming started in early 1962, Ian Fleming had been trying for a decade to get his spy on screen, but as the October 5 release date neared, little about the first James Bond film suggested it would fare much better than Andress’s crustacean attackers.

Attempts to sell Bond to filmmakers had come and gone. Even American TV was cool on the idea of a British spy. When a live adaptation of Casino Royale did arrive on CBS in May 1954 – following an American James “Jimmy” Bond – it misfired.

Another attempt by Fleming led to a 28-page outline of a series called James Gunn – Secret Agent for CBS in 1958. Again, nothing happened, but Fleming sharpened what he wanted his spy to be on screen.

“There should, I think, be no monocles, moustaches, bowler hats, bobbies or other ‘Limey’ gimmicks,” Fleming wrote to CBS head of television Hubbell Robinson. “There should be no blatant English slang, a minimum of public school ties and accents, and subsidiary characters should generally speak with a Scots or Irish accent.”

Finally, after John F Kennedy had picked From Russia With Love as his one of his 10 favourite reads in 1961, Albert ‘Cubby’ Broccoli partnered with Canadian producer Harry Saltzman to get hold of the rights to Fleming’s works.

They wanted to start with Thunderball, about the criminal gang SPECTRE stealing two nuclear bombs and holding the West to ransom, but the rights were snarled up in a legal dispute. So, they turned to a story Fleming had started putting together for an American TV series called Commander Jamaica before making it a Bond novel: Dr. No.

Writers Wolf Mankowitz and Richard Maibaum worked together on the first script, and decided it needed a new villain – Dr. No, they felt, was too much like Fu Manchu. Instead they added a new villain called Buckfield. In Broccoli’s recollection, Dr. No was now Buckfield’s pet marmoset. The script was rejected.

Now they needed a Bond, and Broccoli knew the man for the job: Cary Grant. The two men were close – Grant was Broccoli’s best man – but at 57 Grant felt he was too old and would only commit to one film.

James Mason, Patrick McGoohan, Richard Johnson, Richard Todd and David Niven were all considered and discarded. Roger Moore was in Broccoli’s thoughts, but was “too young, perhaps a shade too pretty”.

To speed things along, in early 1961 Daily Express showbiz editor Patricia Lewis devised a competition to find a James Bond, judged by a panel including Saltzman, Broccoli and Fleming. Professional model Peter Anthony was a Londoner who had been a regular in Man About Town, a magazine which captured a proto-Bond lifestyle: cars, suits, fine food and drink.

An image from a spy-themed shoot got the producers’ attention, and in September 1961, he was announced the winner, beating other finalists including two salesmen from Warrington and Bolton, and an aerial ropeways engineer from Essex. Broccoli noted his “Greg Peck quality that’s instantly arresting”. Unfortunately, that quality Anthony had wasn’t Peck’s acting skill.

The only name the producers came back to was Sean Connery. When he met the producers, Connery had turned up looking unkempt and disinterested, and thrown his weight around to telegraph some machismo. As he left, Broccoli and Saltzman watched him walk to his car. “He moved,” Broccoli remembered, “like a jungle cat.”

Connery’s rough edges made an impression. “To be candid, all the British actors lacked the degree of masculinity Bond demanded,” Broccoli wrote in his autobiography. “I was convinced he was the closest we could get to Fleming’s superhero.”

United Artists were unimpressed by Connery but Broccoli dug his heels in. To check, he and his wife Dana settled into a theatre at the Samuel Goldwyn Studios. Broccoli watched his wife’s reaction to the only bit of Connery footage they had to hand: Walt Disney’s begorrah-and-blimey Irish fantasy Darby O’Gill and the Little People. Dana knew immediately that he was right.

Broccoli followed his other hunch too: that his and Saltzman’s sixth choice of director, Terence Young, would fit Bond. To show him how to be an English gent, Young took Connery under his wing. His influence on what Bond became was enormous.

“He was very much up on the latest shirts and blazers and was very elegant himself – whether he had money or not – and all the clubs and that kind of establishment,” Connery told Variety in 2002. “And also he understood what looked good – the right cut of suits and all that stuff, which I must say was not that particularly interesting for me. But he got me a rack of clothes and, as they say, could get me to look convincingly dangerous in the act of playing it.”

Filming started in Jamaica, where a reporter from the Daily Gleaner newspaper dropped by to watch proceedings. “If the first day’s shooting was any indication of the quality of the finished product, Dr No promises to be a slapdash and rather regrettable picture,” the reporter sniffed.

Script doctor Johanna Harwood and thriller author Berkely Mather had polished up a second draft script by Maibaum but the reporter was unimpressed: “What I have heard of the dialogue is appalling.”

When the production returned to the UK, things were equally tricky. “It was a disaster, to tell you the truth, because we had so little money,” set designer Ken Adam told the Guardian in 2005.

Dr. No’s lair called for an aquarium filled with sharks. “We decided to use a rear projection screen and get some stock footage of fish,” Adam recalled. The budget limited their options. “The only stock footage they could buy was of goldfish-sized fish, so we had to blow up the size and put a line in the dialogue with Bond talking about the magnification.”

The style and panache which Broccoli insisted Young could bring to Dr. No was there in the scene which introduced Bond himself, playing baccarat at the Les Ambassadeurs club. Like much of the rest of the filming, though, it proved awkward.

Eunice Gayson, who played Sylvia Trench, remembered the day as fraught. She’d already had to swap into a red dress – a size 20 hacked down to roughly her size eight and held together with clothes pegs – and now Connery was struggling.

“I’d known Sean for years and I’d never seen him so nervous as he was on that day because of all these delays,” Gayson said. “He had to say, ‘Bond, James Bond’, but he came out with other permutations like ‘Sean Bond’, ‘James Connery’.”

Young told Gayson to go and get Connery a drink and calm him down. The director took inspiration from William Dieterle’s 1939 film Juarez, which introduced the Mexican revolutionary Benito Juárez by shooting his back until he turned to introduce himself.

First, Bond’s hands nonchalantly flipped cards over, then Young drew back over his left shoulder. The hands took a cigarette from a silver case, and paused. Gayson fed Connery his line again. “Bond,” said Connery, cigarette dangling from the very edge of his lips. “James Bond.”

“It was so wonderful,” Gayson remembered. “The day took off from that moment – he was so relaxed.” Some were less enthused. After seeing early rushes, Mankowitz had his name taken off the credits because, he said, “I don’t want my name on a piece of crap”. But elements of the Bond iconography started to come together. Monty Norman was a singer and composer who’d knocked out hits for Cliff Richard and Tommy Steele, and had been tasked with writing a theme tune for Bond.

He looked at a score he had put together for an unproduced musical version of VS Naipaul’s A House for Mr Biswas. A winding, four-note tune for one song called Bad Sign, Good Sign seemed to fit, though its original lyrics didn’t: “I was born with this unlucky sneeze, and what is worse I came into the world the wrong way round.” John Barry took Norman’s theme and vamped it into something slinky and propulsive.

The London Pavilion on Leicester Square hosted the premiere on October 5 1962. America did not immediately swoon en masse. Time magazine called Bond “a great big hairy marshmallow” who “almost always manages to seem slightly silly”.

But slowly, the wave of adulation reached both seaboards and beyond. It took roughly $60 million across the world, somewhere around $540 million today. Though Connery would become weary of Bond, he knew why it worked. “They were exciting and funny and had good stories and pretty girls and intriguing locations,” he said in 2002. “And didn’t take anything for granted.”