Examining the racist roots of fat phobia and diet culture

When it comes to diet culture, not all bodies — and races — are treated equally.

When it comes to diet culture, not all bodies — and races — are treated equally.

In fact, because of the racist origins of fat phobia, Black men and women have been at a disadvantage for centuries, Sabrina Strings, an associate professor of sociology at the University of California at Irvine and the author of “Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia,” explains to In The Know.

“By the middle of the 18th century, because of the fact that the main mechanism for separating ‘free’ from ‘slave’ — which had been skin color — was no longer an effective sorting mechanism, they started to identify new ‘traits’ of inferior and superior people,” says Strings. Their conclusion, she explains, was that “inferior races have no self-control … because of how interested they are in sex and food. This was really the beginning of linking what was considered an unruly type of fatness to Blackness.”

In society and in science, this racist revulsion toward Black bodies has persisted. More frequently than not, when researchers are asked to explain any sort of disparity between white people and Black people, they seemingly ignore the facts and data, and blame it all on what they see as cultural shortcomings.

When scientists in the late 1900s tried to come up with a reason for the health disparities between white people, Black people and Latinx people, Strings explains they concluded that it was “the result of cultural deficits [like unhealthy diets and a lack of self-control] within those racial ethnic minority groups.”

That conclusion was wrong. Science has proven that Black people, on average, tend to be heavier than white people not due to anything related to culture, but rather body composition and bone density. In fact, research presented at The Endocrine Society’s 91st Annual Meeting in 2009 concluded that body fat is likely to be lower in Black individuals compared to white individuals of the same height and weight. (Another 2012 study published in the journal Obesity concluded the same thing.)

However, instead of using this information to inform medical practices and treatments, many researchers have used it to justify the racist beliefs they’ve held all along: that Black people will always be fat and unhealthy, no matter what.

“When it was discovered that, in reality, Black people often tend to be heavier than white people, it was an easy [way for doctors to wash] their hands of any type of culpability or responsibility for the negative health outcomes of Black people,” Strings explains. Once researchers realized that Black people were typically heavier, she says, they started to blame a myriad of health issues within the Black community on weight instead of ordering tests, doing thorough examinations and looking deeper into the root causes of things.

Online, people will also pick at Black people’s weight and automatically assume that they are unhealthy if they are “fat.” Plus-size influencers and celebrities — particularly ones like Lizzo and Jessamyn Stanley who move their bodies every day and engage in rigorous workouts — fight back against these ignorant presuppositions, but trolls are adamant that they know more about the health and well-being of the Black community than Black people do.

Rather than coming up with less biased measurements or even recognizing the bias within the research being conducted, most doctors and health experts continue to subscribe to the notion that Black peoples’ health problems are caused by obesity — something they could easily fix with the right diet and exercise regime.

“There is this sort of interiority to the logic where any time a person is not doing well, it’s their own fault,” says Strings.

This “solution” not only ignores the bias of measurements like BMI, but also fails to consider the fact that many Black men and women simply cannot afford to spend hundreds of dollars on organic groceries and hit the gym every day.

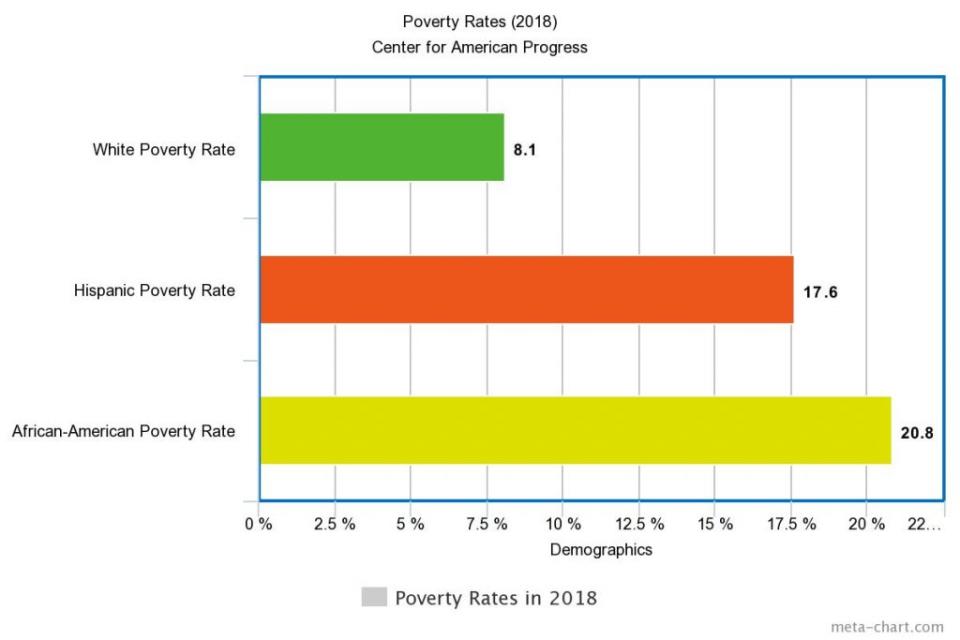

According to data from the Center for American Progress, 20.8 percent of African Americans fell below the poverty line in 2018, compared to just 8.1 percent of non-Hispanic whites.

An analysis of food accessibility from PolicyLink and The Food Trust also found that food stores in lower-income neighborhoods are less likely to stock healthy foods and have higher prices compared to stores in higher-income or predominantly white areas. These geographic areas with limited access to affordable and healthy food options are called food deserts, and according to the Food Empowerment Project, they are most often found in predominantly Black and low-income communities.

This tendency to dismiss Black patients’ concerns and health issues has led to silent suffering, particularly within the eating disorder community.

In a 2019 study published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings, researchers analyzed hundreds of patients with eating disorders and found that minorities “were statistically significantly less likely to ever seek help for [binge-eating disorder] than were women or non-Hispanic whites.”

“A familiar paradigm has encouraged clinicians and the public to imagine that eating disorders are exclusive to frail, affluent girls of white race,” psychologist Leslie Sim, Ph.D., wrote in response to the findings. “The conventional patient demographic profile as represented in popular culture has failed to resonate with a sizable portion of those with the illness, and this has considerable implications for treatment outcomes and illness burden.”

“If you have unexamined bias, it absolutely affects the way that you do your work in the world.”

According to Chrissy King, an anti-racist fitness and strength coach and creator of the #BodyLiberationProject, unchecked implicit bias — which occurs when someone has a preconceived notion about a group of people without realizing it — plays a major role in how Black people are treated.

“Even if you’re the most well-meaning individual in the world, if you have unexamined bias, it absolutely affects the way that you do your work in the world,” she tells In The Know. “If you have a bias around someone in a larger body, if you have a bias around a particular race or ethnicity or a particular group of people, even if you don’t understand that you’re subconsciously holding these biases, it’s absolutely having a negative impact on the care that you’re providing.”

As a fitness coach, King has witnessed firsthand the impact of implicit bias not just from individual providers, but from the industry as a whole, which she says “really centers and caters to whiteness.”

“If you go to any prominent wellness conventions, the majority of speakers are overwhelmingly white, overwhelmingly thin [and] overwhelmingly male,” King explains. Although companies and wellness leaders claim to be promoting inclusivity and representation, she notes that “none of those things are actually happening.”

Though medicine and diet culture have a ways to go before they’re inclusive and accepting of all bodies and races, there are things people can do in the meantime to contribute to the conversation and keep their unexamined biases in check.

“If you’re not actively doing the work to see how white supremacy is ingrained in every single thing that happens in this country, you can’t be doing the work of anti-racism,” King says.

Strings adds that women in particular need to be more cognizant of the comments they make toward other women. Even a seemingly harmless glance can completely alter the course of a woman’s day: In one British study of 44 young women, the majority of subjects said that the looks they received from women on a daily basis were “judgmental” and that they often felt like they were being judged on their appearance.

Though men were “largely involved in the construction of [the] hierarchies” that rule our patriarchal society, historically, “it’s been women who have been policing other women’s bodies,” Strings says.

“Day-to-day, on the ground, a lot of the body policing that takes place, takes place between women,” she explains. “There’s a way in which thinking through how to stop this kind of oppressive behavior really requires a lot of us who are not cisgender men to rethink our orientation to ourselves and to other marginalized people.”

Our team is dedicated to finding and telling you more about the products and deals we love. If you love them too and decide to purchase through the links below, we may receive a commission. Pricing and availability are subject to change.

Check out these 14 Black-led LGBTQ+ organizations to donate to right now.

More from In The Know:

This all-female Mariachi band is challenging gender norms

Shop our favorite beauty products from In The Know Beauty on TikTok

Shop Black and excellently with these 10 Black-owned brands

Subscribe to our daily newsletter to stay In The Know

The post Unpacking the racist roots of fat phobia and diet culture appeared first on In The Know.