"This Time Is Different Because Iranian Women Are Willing to Sacrifice Everything"

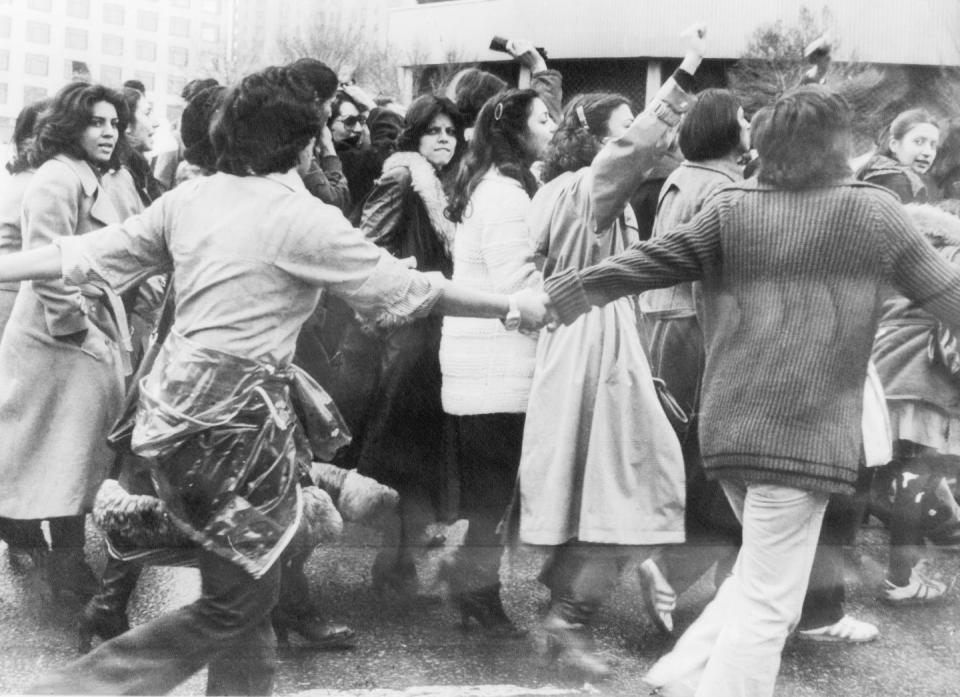

On September 16, Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Kurdish Iranian woman, died after being detained by Iran’s so-called morality police. Her death ignited a long-simmering anger in the people of Iran and sparked a revolution, largely led by young women, demanding an end to the Islamic regime. For the past six weeks, they’ve faced brutal government crackdowns, but they remain undaunted, adopting the Kurdish rallying cry: "Woman. Life. Freedom."

Harper’s BAZAAR has asked celebrated Iranian writers, artists, journalists, and more to help make sense of this moment when so much is at stake. Their stories are collected here, with more to come.

In 2014, journalist Yeganeh Rezaian and her husband, fellow reporter Jason Rezaian, were arrested and imprisoned in Iran on false charges of espionage. Rezaian was jailed for 72 days, with 69 spent in solitary confinement, while her husband was detailed for 544 days in the country's notorious Evin Prison.

As a women born in Iran, Rezaian grew up understanding the suppressive power of the country's Islamic regime firsthand. She was raised under its mandatory hijab laws and other rules controlling the bodies and actions of women, and experienced harassment at the hands of the country's morality police. In 2009, in the wake of an election widely seen as rigged by the government of then-president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, Rezaian was among the many who took to the streets as part of large-scale pro-democracy protests. They were ultimately met with a violent crack-down by security forces. As a reporter who's worked within Iran and is now a researcher for the Committee to Protect Journalists based in Washington, DC, she's an expert (backed by her own lived experience) in the social and political factors that have shaped the modern-day Islamic Republic.

As protests currently unfold in the country following the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini while in the custody of morality police, we asked Rezaian to give us a primer on the long fuse—from the Revolution of 1979 to the Green Movement of 2009 to now—that has ignited a potentially transformative new chapter for the Iranian people.

The people of Iran have a history of fighting for freedom. The Islamic Republic began after the regime co-opted the Iranian Revolution in 1979. In 2009, Iranians protested against the regime in a way that gained national attention, but were brutally suppressed by the government. Within that context, would it be an accurate statement to say that this time is different?

I think it is an accurate statement. In all of my conversations, everyone feels the difference. Young Iranian women and other groups in the country have come to the conclusion that they don't have anything else to lose, and that small reform in the current system is not possible. Women particularly are tired of being second-class citizens in their homeland.

When Mahsa Amini she died in custody, the protests started with women—and very young women—going into the streets to support her and what she went through and to protest that dark fate that was brought upon her by the system. Then the young women stayed out.

Let's be honest, this is a gender apartheid that the regime has imposed on women for over 40 years. And it's not just about the compulsory hijab, it's about every other aspect of being a woman. Iranian women's value is half of men. If they get hit by a car, the value that the driver has to pay is half that of what they pay if the victim was a man. If they get divorced, no matter what the relationship between the husband and children is, regardless of if he is a drug addict or alcoholic or abusive, the father automatically gets the custody. And if the father is not in a reliable condition to take the children, custody doesn't necessarily transfer to the mother. It goes to the next male guardian, like a grandfather or an uncle.

I experienced that gender apartheid when my husband was in jail in Iran. As his wife, as a woman, I had very little rights when it came to seeing him, being able to visit him, being able to go to different offices like the judiciary or foreign ministry and submit my requests. And my husband did not have his father—my father-in-law passed away many years ago. So who would go and advocate on his behalf if not me?

Women have very little rights in Iran under this regime. So it feels different because women are willing to sacrifice everything they have, which is their life folded in their hands.

What led to the 1979 revolution, what has life in Iran been like in the aftermath, and how did it bring us to today's protests 43 years later?

The 1979 revolution was a long simmering uprising against the exercise of a monarchy that was out of touch with the populous. People felt at the time that Mohammed Reza Shah was a tyrant. He couldn't tolerate dissenting voices and used his security forces, known as SAVAK, to imprison and execute many Iranians. The Revolution was compromised of groups from many different political camps back then. But the Islamic faction, led by Ayatollah Khomeini, co-opted the broad-based movement and quickly rooted out all other parties as soon as the revolution happened. When the Islamic Republic was founded in 1979, the impacts on women were immediate. The most obvious was the mandatory hijab. Beyond that, there were many ways in which it was enshrined in the new system that women were considered lesser than men.

But since the beginning of the Islamic Republic, women have pushed back against those limitations. And they have had varying degrees of successes here and there. For example, they pushed back against a decision to limit women's access to several university courses. At one point the Islamic Republic announced that women cannot study several types of engineering courses. As if we don't need female electrician! Can you believe that? The idea was that women should not work in an environment that is mostly occupied with men. So we don't need woman construction workers, we don’t need woman civil engineers, we don't need woman architects. Iranian women pushed back and they had some successes in those areas. But where they’ve advanced significantly has been in terms of their levels of education overall. It was reported a few years ago that more than 70% of university students were women. So that is another difference in these protests this time around. The young Iranian women who have taken to the streets are much more educated than my generation and our mothers' generation.

They're also much more connected to the outside world, which Iranian women traditionally were not. I’ll give you just one example: Sarina Esmailzadeh, who was killed in the city of Karaj, was 16 years old. She spoke fluent English. She had three different YouTube channels. She made beautiful content on her phone that she published on those channels. Those channels were of course removed by the regime, so they are no longer accessible. But in the videos that have been saved by her supporters after she was killed, you see a 16-year-old from the city of Karaj—not even the more metropolitan Tehran—who speaks fluent English and sings American songs perfectly.

So you can see how this generational shift has brought women out of their traditional roles. Our mothers controlled the kitchen. But as much as those traditional values and lifestyles are still considered beautiful and celebrated, young Iranian women are demanding more. They want to be astronauts, they want to be YouTube stars, they want to be actors. They want to be seen, first and foremost.

How are today's protests in Iran different from those that happened in 2009?

The 2009 protests were about a rigged election, but today’s protests are about the entire system. In 2009, we were chanting, "Where is my vote?" This time around they're chanting, "Death to the dictator!"

Back in 2009, we thought that if there was just a little bit of economic prosperity, if our Iranian passport worked a little bit better, if we could travel abroad and go to Dubai to have a drink let our scarves down and let the wind in our hair for a few days, that would be good enough. But none of that is good enough.

So what are the lessons? One lesson is that demanding small changes in the system is not going to work. That's why today's protesters are demanding fundamental change. These protesters are not asking for financial reform, although that is one of their demands. They are not asking for an end to the government corruption, although that too is one of their demands. The system is not designed for compromise. What people are chanting is: “Woman, life, freedom.” Women want to take their lives and their freedom back from this regime.

The other lesson is that they know their demands are going to come with high costs—and we have seen that they are willing to risk that. Amnesty International recently reported that least 23 kids, ages 11 to 17 have been killed. At least. So the protesters are not there to negotiate anymore. They are taking a huge risk and I hope that there will be a day where we can honor their lives. They should not die for nothing.

In 2009, the Iranian government cracked down on social media to suppress protests by preventing information sharing and on-the-ground organizing? What's the role of social media in today's protests?

Social media plays a major role in connecting people on the ground together and connecting them to the outside world. Even though the regime can easily shut off internet or social media—and they have shut down Instagram and WhatsApp—social media still helps the protesters be seen and heard, and lets the world witness the brutality that the government’s forces are using against civilian and peaceful protesters. If it wasn't for social media, we wouldn't be able to see and understand the scope. But it can also be difficult to verify some of these photos and videos. That's where responsible and independent journalism comes into the equation in a critical way.

Social media has also played a major role in the past decade or so by educating and empowering this generation of Iranians. They are connected to American friends, to people of their age all over the world. They see the lifestyle, the education system, and the opportunities those friends have in their countries.

If you want to support a movement in an authoritarian society, you have to help the people online.

What's been the role of journalists during these protests as they operate in a country without the freedom of press?

At the Committee to Protect Journalists, we have documented the arrest of at least 40 journalists since the beginning of these protests—and half of them are women. That is very telling. Not only there are more female journalists in Iran in recent years, but they're willing to go out and risk their safety to report on their sisters and their demands. These were not the things you would naturally see back in 2009 when my generation was out in the streets protesting, and it is not what you would have seen back in the days during the 1979 revolution.

Iran has never respected freedom of the press. There's nothing like freedom of expression enshrined in their constitutions in the way that you see in the western world. All media is state-run media. The government heavily monitors everything that gets published in newspapers or airs on television or radio.

Journalists have traditionally had a very difficult time reporting things as they are because they are accredited by the regime. There are instance I know of personally when the regime issued a message to journalists saying, "If we see you in the street, we will know who you are and we will arrest you."

So there are topics that are known as off limits. For example, any negotiations with the US is off limits. Iran's dealings with China or Russia or North Korea are off limits, human rights topics are off limits. Yet they have done a brilliant job of informing the world using social media as much as it has been available to them, through the use VPNs, which is all very risky.

And I must give a huge shout out to citizen journalists. In the absence of traditional journalists being allowed to go out in the streets, citizen journalists have carried their torch beautifully, reporting what’s happening on the ground.

The Iranian government has taken brutal suppression tactics against peaceful protesters and the people posting and reporting on their violent tactics. What have been the effects of that on the ground?

The government suppression has been very swift. In multiple cases that we’ve documented at the CPJ, journalists would report on the protests on their Twitter account in the afternoon, and they would be arrested overnight. But the swiftness in trying to eradicate protesters and reporters was obviously intended to make the protests die out. But people have been able to sustain themselves and still organize and still post pictures and videos for over five weeks at this point.

There have been widely publicized cases of public figures in Iran speaking out and being suppressed in the past month. After rock climber Elnaz Rekabi competed in a championship abroad without her hijab, there was international concern for her safety. When she landed back in Iran, she was greeted with a hero's welcome by crowds of Iranians. Is this a sign that the government's tactics are backfiring?

I do think their tactics have backfired. People have seen forced false confessions on TV for over four decades. They don't believe them anymore. They have seen how celebrities have been silenced over the years. So they know if a celebrity disappears, it's the regime. People know all the regime’s old tactics.

What have been your personal experiences with the mandatory hijab and its enforcement by the so-called morality police?

My parents were already young adults when the revolution happened and I was raised in a secular, middle class family living under a theocratic regime. My mom was a housewife, and my dad had a master's degree and was much more open minded than many men of his class.

I remember when I was five years old, my mom took me to a photography studio because I had to get a headshot as part of the process for being enrolled in kindergarten. I had to wear a headscarf for the photo, otherwise, the education system wouldn’t accept it. Oh my God, you should have seen me. I was a very little girl, smaller than other girls my age, extremely thin and short. The scarf came down to my knees and I felt terrible about myself despite growing up seeing my mom wearing it. I barely ever heard my mom complain about it, but I complained about it from the age of five years old.

My dad always told us, "Don't do anything to get yourself in trouble with these thugs. I don't want to come and beg for my daughter back.” I have had experiences with the morality police, and I could always hear my dad’s words in my head. While we call them the “morality police,” they are not real police forces. They are a militia trained for this job. They are extremely violent. They don't shy away from badmouthing you, beating you up, scaring you by any means. It's a terrible experience that no one should go through, let alone a young girl.

I was arrested multiple times and taken into custody for long hours. Imagine that you are a teenager full of life and happiness and excitement—and all of a sudden you’re a criminal. They take you away from your family and loved ones to an unknown location and keep you there for extended hours—in some cases days. There is no due process. It takes hours for your family to even locate you because nobody tells them where they took you. All because you showed a few strands of hair.

Do you think Mahsa Amini's death sparked such an explosive reaction because the events leading up to it were so familiar to so many women in and from Iran?

Exactly, yes. Everyone has such an experience. But back in the day, my dad always said, “I don’t want beg for my daughter back." He never thought, "I don't want my daughter to be killed." He had no idea that he should be worried for my life. Of course, through the years there have been so many stories of sexual assault in custody, which became a major worry for families. And in recent years, they became worried about their lives too.

What do you want readers following the events in Iran to understand? In what ways can they support the protesters and the Iranian people?

I want my fellow Americans to support us by talking about these new rounds of protests. I live in Washington, DC and since the beginning of these protests back in Iran, there have been weekly rallies every Saturday organized by groups of Iranians where everyone is welcome to join, regardless of their background or politics. Yet I don't see many Americans joining us. I want my El Salvadorian American neighbor to join me, I want my Lebanese American neighbor to join me, I want my Italian American neighbor to join me. It can sometimes feel as if we are very alone. The Islamic Republic is a dictatorship that needs to go. And one less dictatorship on our earth will make it a better place for all of us, not just for Iranian people.

And I want readers to understand that the Iranian people, like the people of any country, are not the same as the government and system ruling over them. And in Iran's case, the difference is stark. You will find that Iranian women are be among the most passionate, feminine, fashionable, beautiful smelling women around the world. We care about all these things! And I can't wait for the day when we can freely express those parts of our identity in our own homeland.

I was born in 1984, I was born and raised in Iran. I am an outcome of this regime. I was supposed to be a defender and supporter of this regime—but as you can see, instead they did a great job raising many of us to fight against them.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

You Might Also Like