Thatcher aprons and Starmer flip-flops: Why is political merch so embarrassing?

After a week of tedium, it’s become near-official: the election will not happen in May. But it will happen this year, and so we need to be prepared. I don’t mean that in the political sense, but – in a more important way – a sartorial one. We have to gird ourselves for the return of political merch, political memes, and the slow march towards the end of the political slogan tee.

Its death knell came in the form of “Sparkle with Starmer”, a limited edition and unisex £20 tee meant to encourage us to “unleash [our] inner shimmer and shine”, and released in the wake of Keir Starmer being glitter bombed by a protester during the Labour conference in October. The stage invader was a member of People Demand Democracy, a campaign group advocating for changes in the UK’s voting system, and the establishment of a “permanent citizens assembly” to replace the House of Lords. As political attacks go, I don’t think it’s exactly the sexiest one. Judging by the fact that Labour’s website is still selling the supposedly limited edition tee three months after its release, I’m not alone.

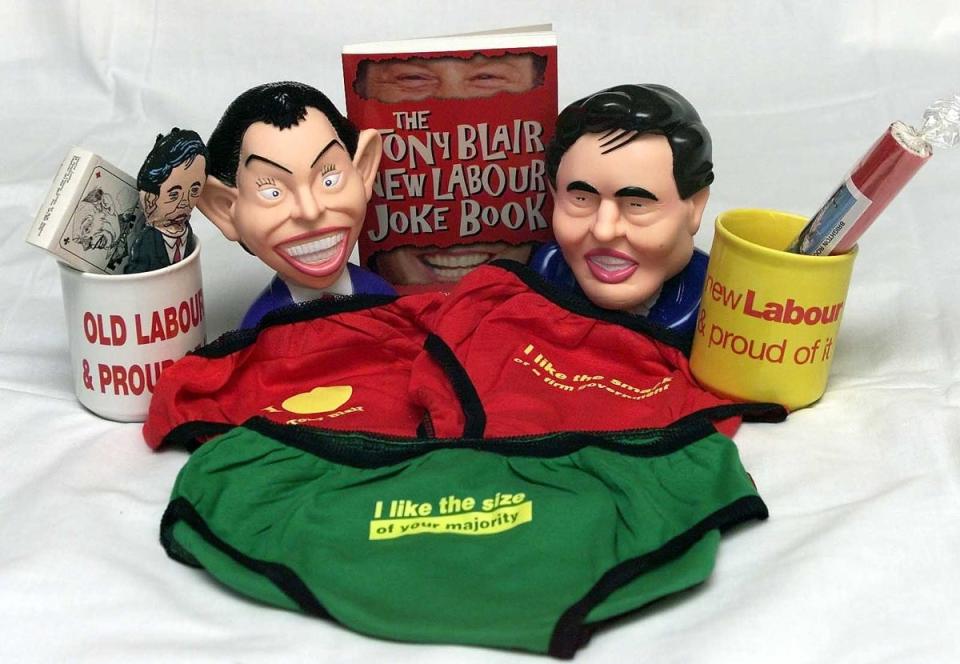

What happened? It wasn’t always like this for the detritus and tat that make up political merch. It’s not a problem specific to the left either: the Conservative Party’s online shop has some truly painful offerings too, from Starmer-themed flip-flops (get it?), to Margaret Thatcher Christmas jumpers (no no no instead of ho ho ho, get it?) and Thatcher aprons (“the lady’s not for burning” written on the front – you get it?). There’s even a selection of Tory leader Toby jugs (bafflingly these are not branded “Tory jugs”), featuring Thatcher again, as well as David Cameron, Winston Churchill, Boris Johnson, Theresa May and John Major. Presumably they decided not to bother to manufacture one for Rishi Sunak, despite the fact he is the current prime minister. It goes without saying that if you were a person with even an iota of good taste, you would not want to wear or display any of these things in your home.

And yet there is a potted industry on eBay for political merch from as far back as the Reagan and Kennedy eras – tees to sweaters to posters to enamel pins reading “I TOLD YOU SO”, selling for absurdly high prices. It can’t just be attributed to nostalgia or a vintage collecting impulse either, modern politicians can make good merch too.

In 2016, Bernie Sanders’s presidential run typography was so popular it inspired Balenciaga – the fashion house’s entire FW17 campaign was inspired by “Bernciaga”, in fact. “One of the things we wanted to create was a logotype that gave a corporate vision very vividly,” creative director Demna Gvasalia said in 2017. “In my research, Bernie Sanders’s was most present at that time; that’s why it resembles it so directly and obviously I was very aware of it. I wanted it to be [similar] – that was my message with this collection.” Bernie became, for a time, if not a presidential candidate then an unlikely fashion sensation. Political merch can have cultural cache, then. It just… doesn’t anymore.

When Sanders was inspiring Balenciaga, though, the political slogan tee was at its apex of chicness in the fashion world. For her SS17 show, Maria Grazia Chiuri was sending models down the runway at Dior wearing T-shirts reading “We should all be feminists”. In the same year Frank Ocean performed at Panorama Festival wearing a t-shirt inspired by a tweet – which inevitably went viral on Twitter afterwards in a full ouroboros moment – reading “WHY BE RACIST, SEXIST, HOMOPHOBIC OR TRANSPHOBIC WHEN YOU COULD JUST BE QUIET”. And in the UK, too, during the 2019 election and later into the pandemic, slogan tees in support of Corbyn and the NHS from artists like Sportsbanger were fairly ubiquitous. This was peak 2010s.

And peak 2010s is anathema to everything currently considered cool. Political swag, maybe, has become lumped in with “twee” and “millennial cringe”, a relic of a bygone era for zoomers who would never dream of pausing before they begin to record a video about voting for Hillary Clinton. The slogan tee itself, in the time between the last UK election and the next, has become the archetype of all that is basic. Slogan tees make us think of Clintonmania, “girlbossing”, 2016 feminism, spin-class tank tops that read “rise and grind”.

These slogans became a certain kind of uniform for a certain kind of woman, or a certain kind of feminine ideal at least. They are or were, Katie Rosseinsky argued last year, the bastardised end point of the protest tee, the ancestor to pre-teen boys wearing Che Guevara T-shirts to school, the antithesis of the DIY fashion Vivienne Westwood created in her early days at SEX. It’s unfortunate too, that in the same period the idea of political “protest fashion” has become more strongly associated with the right. You couldn’t foresee anyone 10 years ago anyone having a problem with baseball caps made in Labour red, but after Maga (Make America Great Again) it would be political suicide to suggest manufacturing one (perhaps sensibly, the only red hat available on the Labour website is a bucket hat).

That distinctly millennial Banksyification of political thought, the girlbossification of feminism, the melding of art and fashion with politics, became so prolific and oversaturated by the time of Jeremy Corbyn and Joe Biden that even without the cast of unloveable rogues we’re set to meet in 2024’s upcoming election season, we would perhaps inevitably have got sick and tired of the spectacle of political merchandise. It became so memeified that, like all memes at saturation point, it simply stopped being funny. It’s also true that politics probably shouldn’t be funny. Nor, if we want to stop electing populists, should it be easily communicable on a crop top.

Because aside from their inherent cheuginess, the obvious answer to the decline in political merch is that slogan tees, by their nature, advertise platitudes rather than communicate the kind of complicated, grudging support the 2024 election season asks of us, on both sides of the Atlantic. You can’t really embrace the ethos of “protest fashion”, nor can you use fashion to make a political statement, if the political statement you’re making is “yeah, fine, whatever, whichever one is the least bad”.

In the UK in particular, the slogan tee became during the last election, among other things, a way of communicating support for the underdog, which is depressing if only because it means we’ve become accustomed to the reality that in Britain, Labour historically lose more often than they win. But, as every new voting intention poll tells us, this time that might not be the case. Starmer’s neoliberal nightmare of a Labour Party is no longer the party of the underdog, but it’s that sentiment his sparkle T-shirt clearly tried – and failed – to mimic.

The most recent figures predict that most young people in the UK will “never vote for the Tories”, a party millennials and zoomers associate with higher tuition fees, a rental crisis akin to feudalism and the increasing certainty that many of us will never own property. But a hatred of one party doesn’t automatically translate to enthusiastic support of the other. In 2019, 60 per cent of 18- to 24-year-olds voted for Corbyn. Five years on, much of that same demographic is more begrudging of his successor than sparkly Starmerites might hope for. In the US, where young people supported the Democrats, they voted for Biden with the same attitude. His successor will most likely enjoy a continued reluctant, grudging support. And if you can barely convince people to turn out and vote for you in a depressing local church hall, on a rainy winter morning (a May election would at least have made this process slightly less miserable), then it’s inevitable that you’re really not going to convince them to pay 20 quid to wear a cheugy t-shirt while they do it.