How do you survive 28 years on death row for a crime you didn't commit? Start a book club

Books, like the radio, take you somewhere else. Even if it’s somewhere you’ve never been before, and have always wanted to visit. Even if it’s somewhere you hope never to go, not in your worst nightmares.

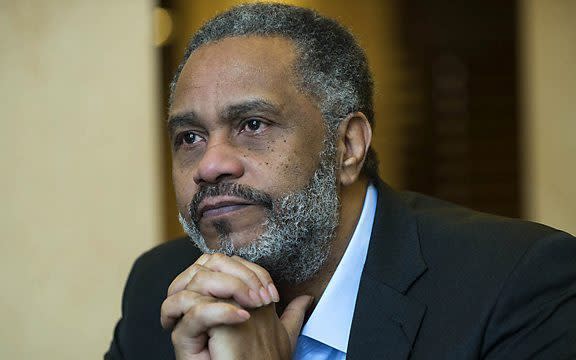

Death Row Book Club (Radio 4, Monday) was an extraordinary documentary originally made for the World Service, and a transformative feat of storytelling. The presenter was Anthony Ray Hinton, who had been sentenced to death in Alabama in 1985 after being convicted of first degree murder, a crime he didn’t commit, in a trial process skewed by incompetence and systematic racism. His conviction was overturned, and in 2015 he was exonerated and freed after 28 years on death row.

But this programme wasn’t an in-depth analysis of the justice system that failed Hinton and the story of the crimes against him, or how his life was stolen from him. It was a story of how, while watching inmates walk past his cell to their deaths in the electric chair, and while angry and trapped, with the stench of electrocuted flesh in his nostrils, he decided to ask the warden if he could start a book club.

“What, are you trying to get one over on me?”, the warden said. But he couldn’t really think of a good reason why not. And so Hinton started his book club, which consisted of six death row inmates. The idea was that the books they read could take them somewhere – anywhere – else. The first book they read was Go Tell it on the Mountain by James Baldwin.

All the books the inmates read together were about race, a subject which had profoundly affected all of their lives. Hinton’s favourite book was To Kill a Mockingbird, finding heartbreaking, overwhelming similarities between its story of a wrongfully convicted black man and his own real-life experience.

All of the other original book club members have since died on death row. Hinton is the only survivor. He told his story with the skill of a man who has read a lot of stories, and seen a lot of terrible things. We heard him holding the paper and turning the pages as he went over the story of his own life. The mood of the documentary was dark and intense, scored by an ominous low hum, reminiscent of a strong current of electricity, as Hinton recalled how, just before an execution, the lights on death row flickered on and off as the generator charged up.

How could an innocent man survive such a place? How could anyone? “A book can give you faith, when you have doubt,” said Hinton, his voice gravelled with sincerity, truth and understatement. “A book is like a nice warm blanket on a cool day.”

There are some sounds, like that low electric hum, that seem to sink under the skin and stay there. Another was to be found in the haunting, melancholy moan of sea foghorns — one or two low notes, long and slow, followed by silence — in Life, Death and the Foghorn (Radio 4, Tuesday), writer and broadcaster Jennifer Lucy Allan’s “eulogy for foghorns”. Foghorns are disappearing; ever less important for ships’ navigation in the age of ever more complex technical instruments on board, they are not being maintained and gradually being allowed to fall into disrepair.

The sound of foghorns, at once both mournful and consoling, seeps into the consciousness of people at sea and those who’ve swallowed the anchor. “It just sounds like somebody trying to wake the dead… or rather keep you out of the grave, maybe,” said Mike Nicholson, former sea captain and now Port of Tyne harbourmaster. “If I close my eyes I can still hear it.”

Jennifer Lucy Allan and producer Jack Howson structured the programme around a funeral service, which was a good idea, but occasionally clunked a little heavily. The many fascinating contributions would have benefitted from more space to breathe. Still, the passion of all the foghorn enthusiasts, musicians and poets compelled, while the moody soundscape became a ghostly, entrancing response to the call of the foghorn’.

The most poignant moment was photographer John Moir’s recollection of a foggy December night in Vancouver, near the care home where his mother was suffering from dementia. On the night she died, he heard the foghorn being sounded. And he hoped that, in his mother’s final moments, the familiar sound of the coastline she knew might have called to her, too, through the fog of dementia, and reminded her, right at the end, of who she really was, and that she was loved.