‘They’re quite like us’: Scientists reveal groundbreaking finding on Stone Age piercings — and who wore them

Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

Archaeologists in Turkey have discovered groundbreaking evidence connecting prehistoric facial piercings to the bodies of the people who wore them.

Personal adornment — including earring-like objects thought to be worn as piercings — has been documented among Neolithic or late Stone Age peoples in multiple locations across southwest Asia, with evidence from as far back as 12,000 years ago. But none of the objects interpreted as piercings had previously been directly associated with body parts where they may have been worn.

Now, analysis of excavations at the archeological site Boncuklu Tarla in southeastern Turkey has revealed burials in which adornments for piercings were found placed near grave occupants’ ears and mouths. Dental wear on the lower incisors of these remains, dating to around 11,000 years ago, resembled known wear patterns caused by abrasion from a type of ornament called a labret, often worn below the lower lip.

This is the first time that facial piercings in Neolithic people from southwestern Asia have been directly linked to the body parts that they perforated, researchers reported Monday in the journal Antiquity. Their findings further confirm that the practice was already common during the early Neolithic.

People of all ages were buried at Boncuklu Tarla, but the newly described ornaments were found only near the remains of adults. This suggests that such adornments were not worn by children, and acquiring these piercings may have marked coming-of-age rituals within social groups, according to the study.

There are some other types of evidence for coming-of-age rituals in the Neolithic, such as burials that arrange the body with certain artifacts “or the placement of the deceased in particular locations prescribed for a particular age group,” said anthropological archaeologist Dusan Boric, an associate professor at Sapienza Università di Roma in Italy, in an email.

“But I cannot think of many other examples as convincing as this one,” said Boric, who was not involved in the study.

‘Unbelievable’ quantity

Hunter-gatherers occupied Boncuklu Tarla from around 10,300 BC to 7100 BC, as people began to shift away from a nomadic lifestyle and form settlements. The site was first excavated in 2012 and has since yielded a bounty of ornamental objects from the Neolithic period, with approximately 100,000 decorative artifacts found to date — a staggering number, said study coauthor Dr. Emma L. Baysal, an associate professor of archaeology at Ankara University in Turkey.

“The sheer quantity is unbelievable. This is a site of people who just adore adornment, more than at any other site,” Baysal told CNN. “They had masses and masses of beads and they made complicated things out of beads,” including necklaces, bracelets, animal-shaped pendants and decorations that could be sewn onto clothing, Baysal said.

They also crafted ornaments for ear and lip piercings. Labrets, which are still worn in some cultures in Amazonia and Africa, come in a variety of forms: rounded, oblong and disc-shaped. Some are long and thin, but most have one end that is wider and flattened, and they vary in diameter and width.

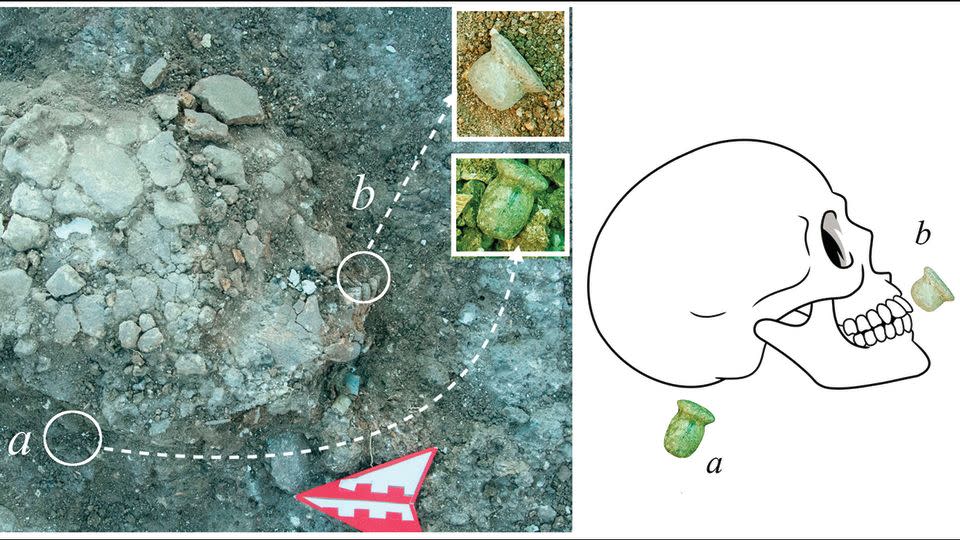

Scientists identified 85 objects from Boncuklu Tarla burials as ornaments worn in piercings, made of materials such as flint, limestone, copper and obsidian. The researchers classified the labrets into seven types, based on shape — all measured at least 0.3 inches (7 millimeters) in diameter, and the longest was just over 2 inches (50 millimeters) in length.

Ornaments described as Type 1 had long shafts and a “nail-like appearance” and were probably worn “inserted into the flesh or cartilage of the ear,” according to the study. Elongated Types 2, 4 and 6 were also thought to be ear ornaments. By comparison, Types 3 and 5 labrets had shorter, more bulbous shafts — better-suited for lip wear. Type 7, a flattened disc, was also thought to be a kind of labret.

Some of the labrets had been dislodged from their original positions in the graves, possibly by rodents, though they were still near the head and neck area of the human remains. Other pieces were still “lodged in position on the upper or lower surface of the skull or under the lower jaw,” the study authors reported.

Scientists have long thought that Neolithic objects called labrets were used as piercings, “especially in relation to the mouth or ear,” Dusan said.

“However, now we have inconvertible and robust contextual evidence from the site of Boncuklu Tarla that here and very likely at other broadly contemporaneous sites such objects were indeed associated with these parts of the body as they were found in burials and were likely worn in the same way in life.”

‘A kind of social status’

Though children were buried with pendants and beads, none had ear ornaments or labrets near their heads, necks or chests, indicating that facial piercings were reserved for adults, the researchers concluded.

“It’s probably something associated with being grown-up,” Baysal said. “Maybe a kind of social status associated with age, or a particular role in society.”

For archaeologists who are working to piece together how prehistoric peoples presented themselves to each other and to outside groups, piercings and other types of body decoration “are the absolute best source of information that we have about people of these periods, until writing is invented and people are directly expressing themselves,” Baysal said.

This form of personal expression may be rooted in the mythologies of traditional societies, Dusan added, in which “a specific genre of myths relates to the origin of ornaments and body decoration, suggesting a fundamental importance of decorating the body as an act that goes beyond purely aesthetic concerns,” he said. “Wearing bodily adornment might rather have been an act of personhood construction and protection.”

More than tools or other artifacts of daily life, these adornments also share a highly relatable view of Neolithic people, as the human motivation to express identity or community through piercings and other personal ornamentation continues to this day.

“When you put earrings on, you can’t see the earrings that you’re wearing. You’re not doing it for yourself, because you can’t see them. You’re doing it for how you project yourself to other people. And I don’t think that has changed for all these thousands of years,” Baysal said. “It’s a way that we can identify with people in the past and think, ‘Well, actually, they’re quite like us.’”

Mindy Weisberger is a science writer and media producer whose work has appeared in Live Science, Scientific American and How It Works magazine.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com