Steve McQueen and the ‘repellent, horrific’ truth about The Great Escape

In the opening minutes of The Great Escape, “the Kommandant” (Hannes Messemer) of the Stalag Luft III prisoner-of-war camp warns Captain Ramsey (James Donald) against trying to escape. Ramsey’s rabble of captured Allied airmen are prolific, well-known escapers – but the Kommandant wants a quiet life. Ramsey, however, is having none of it. As the senior British POW, he tells the Kommandant straight: “It is the sworn duty of all officers to try to escape.”

It’s those words that set the tally-ho, sticking-it-to-Jerry tone of The Great Escape – the indomitable spirit that bobs along to the sound of its much-whistled theme tune.

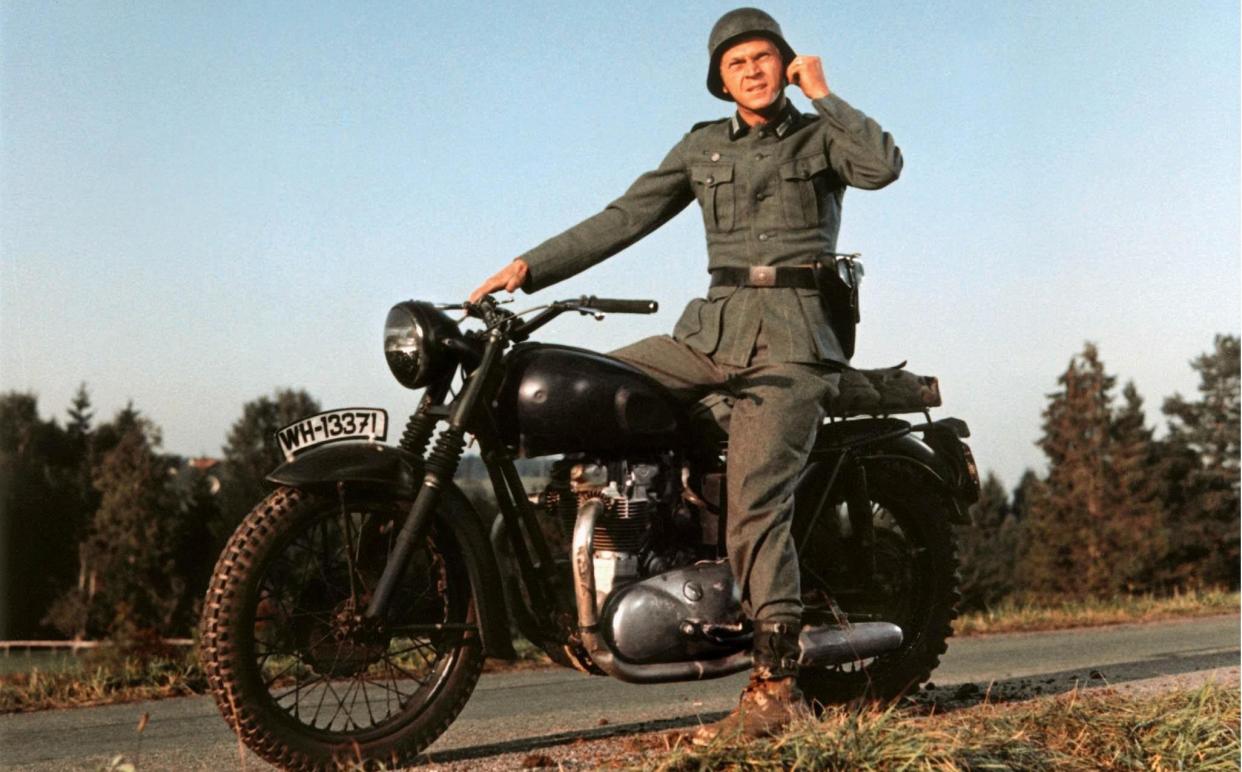

The film, now celebrating its 60th anniversary, is a tremendous, undisputed classic. It’s the stuff that bank holiday afternoons were made for – all machismo, schoolboy pluck, and belly-firing derring-do. The Great Escape is also well known for its flagrant, Hollywood-friendly fabrications, best personified by Steve McQueen’s Captain Virgil Hilts – a wholly invented motorcycle rebel. Starring alongside McQueen is in a line-up of based-loosely-on-fact or fictional POWs: Richard Attenborough’s mastermind; Donald Pleasence’s almost-blind forger; James Garner’s fast-talking scrounger; and Charles Bronson’s claustrophobic digger. The Great Escape plays as much like a heist as a prison break.

For the most part, however, it’s a broadly accurate retelling of how, in March 1944, 76 POWs tunnelled their way out of Stalag Luft III. According to historian Guy Walters, author of The Real Great Escape, it’s the tone that’s wrong.

In truth, there was no duty to escape. There was an expectation, perhaps, that POWs would attempt it – and the God-given right to have a jolly good go – but no actual duty. Also, senior POWs were warned repeatedly to not attempt a mass escape. And not just because German guards wanted a quiet life – because the repercussions would be severe. And indeed they were.

Only three of the 76 escapees made a “home run”. The others were recaptured. Fifty of them – under direct orders from Hitler – were killed by the Gestapo. In the film, even this tragic end has an air of glory. “What people need to realise is that the story of the Great Escape is far darker than the film makes out,” says Guy Walters. “At its heart, it’s a story of recklessness and murder.”

The Great Escape is based on the book of the same name by Paul Brickhill, an Australian pilot, POW, and author. Brickhill, who also wrote The Dam Busters, was shot down over Tunisia and sent to Stalag Luft III in April 1943.

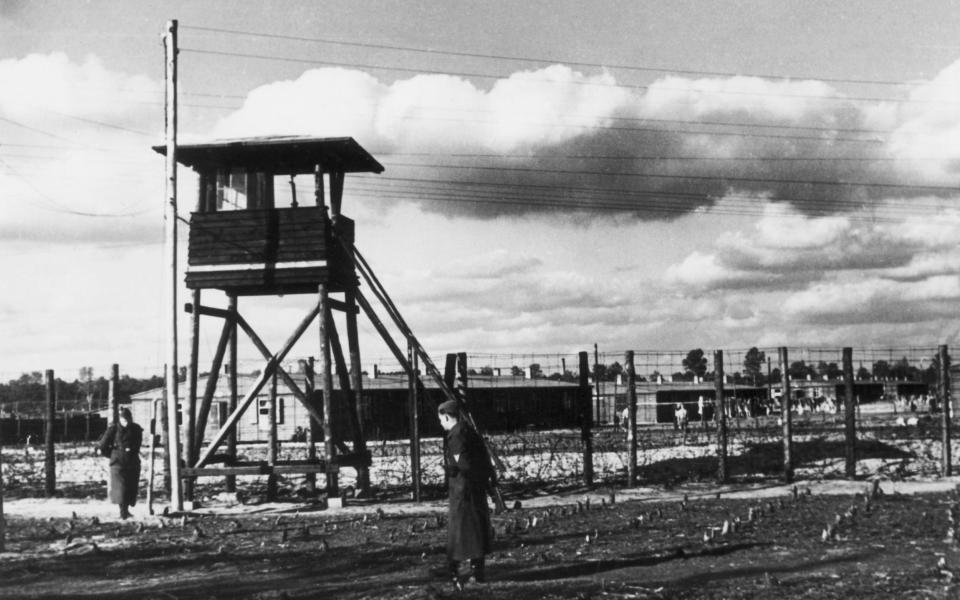

Accounts often describe the camp as escape-proof. It’s true, as claimed in the film, that Stalag Luft III was built specially to hold Allied airmen. Located near Sagan, Lower Silesia (then Nazi Germany, now Poland), it was run by Luftwaffe officers and employed significant measures to prevent escape. Undeterred, some of the Allied airmen – calling themselves “X Organisation” – persevered with a plan to dig three tunnels, codenamed “Tom”, “Dick”, and “Harry” from under their barrack huts.

The operation was led by South African-born pilot Roger Bushell – aka “Big X” – the basis for Richard Attenborough’s character, Bartlett. Paul Brickhill was involved in the operation but didn’t participate in the escape. Bushell debarred Brickhill from escaping because he suffered from attacks of claustrophobia.

Brickhill’s book was published in 1950. Director John Sturges read the story the following year and immediately saw the cinematic potential. “It was the perfect embodiment of why our side won!” he later said. Sturges was a veteran himself – he made documentary films for the US Air Corps during WW2.

He was also the foremost action director of his day and spent more than a decade trying to get The Great Escape made. As described in Glenn Lovell’s biography of Sturges, Escape Artist, the director initially pitched the film to Sam Goldwyn at MGM. “What the hell kind of escape is this?” said Goldwyn. “Nobody gets away!” Sturges’ assistant director, Robert E. Relyea, said similar: “It’s about a bunch of guys in a prison camp who eventually get executed. That’s a tough sell.”

It would also be expensive, and had no female characters. “We have nary a woman,” Sturges said. “They have no place in this story.”

Following the success of The Magnificent Seven – another manly, Sturges-directed ensemble starring Charles Bronson, James Coburn, and Steve McQueen – the Mirisch Company greenlit The Great Escape. But Sturges had to convince another key person: Paul Brickhill. The author had resisted offers to sell the rights. Brickhill didn’t want the story to become a Hollywood romp full of stars-and-stripes glory.

Sturges met with Brickhill and persuaded him, using Hollywood schmooze, a gift of mink gloves, and promises of staying faithful to the real events. Brickhill also sought permission from the escapees’ families. But the script was still two years in the making, with 11 drafts and more than half a dozen writers (Harry – the tunnel through which the airmen escaped – took around a year, including a break during the winter months).

Despite assurances of sticking to the real events, both Sturges and the film’s producers wanted to include American stars. And Steve McQueen’s character, Hilts – with his baseball mitt and don’t-give-a-monkey’s charm – couldn’t be more American. Nicknamed the “Cooler King” (for how much time he spends in solitary confinement), Hilts is certainly cool. It’s true that Americans were involved in the early stages of the tunnelling operation, but they were moved to another compound within the camp by the time of the escape in March 1944.

If anything, the film should have more nationalities. “It was very much a multinational effort,” says Guy Walters. “Only 50 per cent of the escapees were British or Commonwealth. There were Lithuanians, Poles, Czechs… you name it.”

Among the more faithful characters is Richard Attenborough’s Bartlett, based on Bushell. (Richard Harris was originally cast but dropped out.) “Attenborough captures that steeliness,” says Walters. “He’s a cold and austere figure to begin with. What I don’t think it captures is that Bushell was quite arrogant. He alienated a lot of people. He was pretty bombastic and reckless.”

Indeed, Walters’ book is critical of Bushell for pushing forward with an operation that was “unsound, doomed, dangerous and superfluous to the war effort”.

In the film, the point of the escape isn’t just to, well, escape, but “to confound and confuse the enemy” – i.e., to force the Nazis to waste valuable resources hunting them down, draw manpower from the frontlines, and hurt the Nazis overall. This was part of Bushell’s reasoning from plotting the escape, and it’s often repeated as fact.

Walters calls this “bunkum”. A mass escape would simply cause the Nazis to increase security, find the escapers, and find people escaping from elsewhere in the Third Reich in the process. “And at no cost to their war effort,” says Walters.

Warnings from the German guards were born out of genuine concern for the POWs’ wellbeing. “The German guards repeatedly warned Bushell and the senior officers,” says Walters. “A mass escape would piss off the Nazis so much that the retribution would be horrific – so don’t do it. They were told, if you’re going to escape, escape in twos and threes. The German guards told them this out of friendliness.”

The film captures the relationship between the POWs, known as Kriegies, and the guards – a sort of cordial understanding that escape is a bit of gamesmanship.

“The German captors were in their forties and fifties, and the prisoners of war were all young men,” says Walters. “There was a schoolmasterly, avuncular, father-son type relationship. A lot of the German guards and officers had fought in the previous war and had children the same age. This wasn’t Auschwitz. By and large, prisoners of war were treated reasonably well by the Germans.”

John Sturges planned to film The Great Escape in California, but problems with the Screen Extras Guild forced them to look elsewhere. Instead, the film was shot at the Bavaria Film Studios in Geiselgasteig, outside Munich. “Guess what Germany looks like?” Robert Relyea told Sturges after finding the location. “It looks like Germany!”

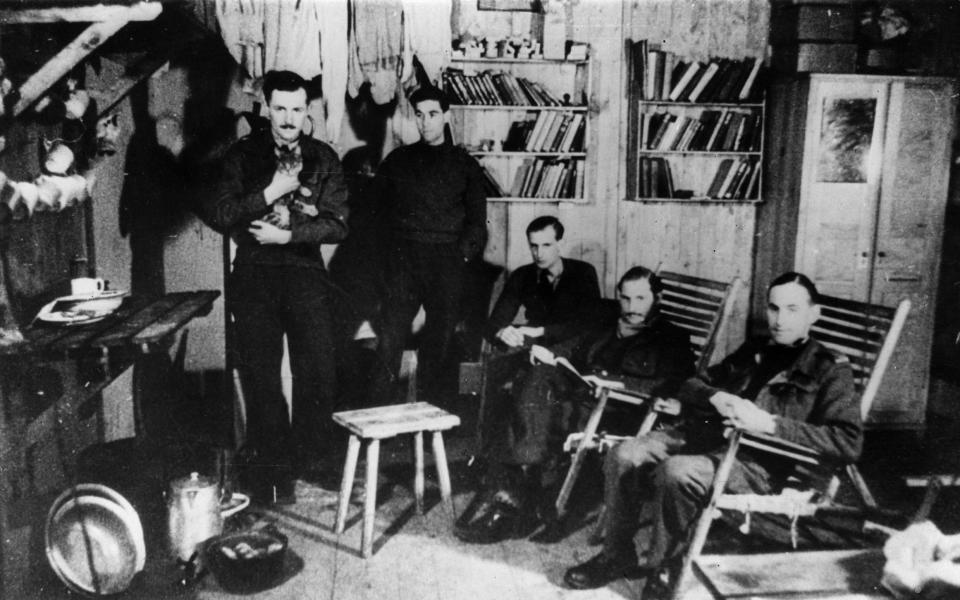

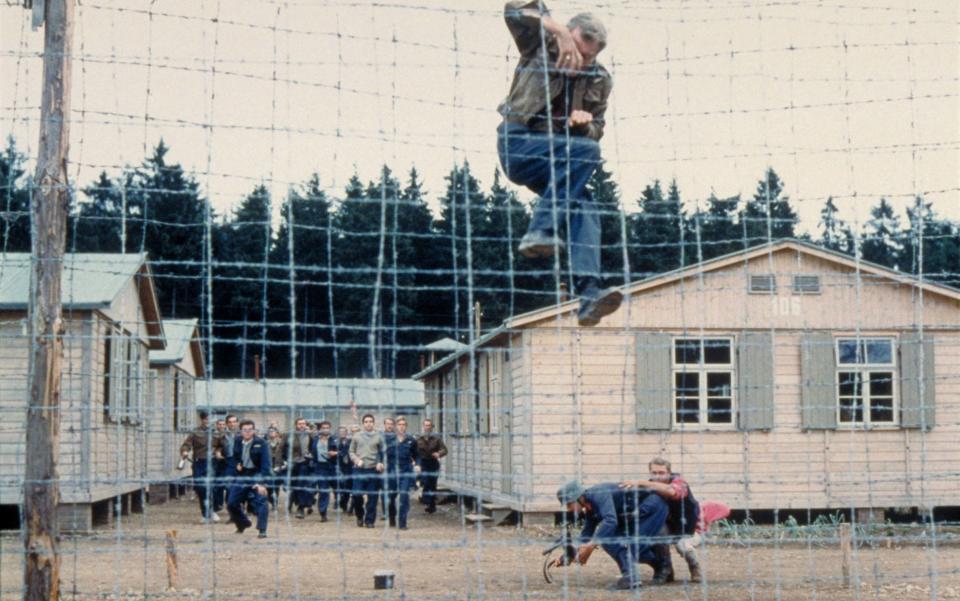

A replica of Stalag Luft III was constructed just outside of the studio. Donald Pleasence called it “an exact reproduction of a prisoner-of-war camp, and just as frightening.” Pleasence certainly knew what he was talking about – he was an RAF wireless operator/air gunner during WW2. Brought down over France in August 1944, Pleasence saw out the war in Stalag Luft I on the Baltic Sea. With the help of technical advisor Wally Floody, a Canadian pilot who had dug the tunnels in the real Great Escape, cross sections of Harry were built on the studio soundstages.

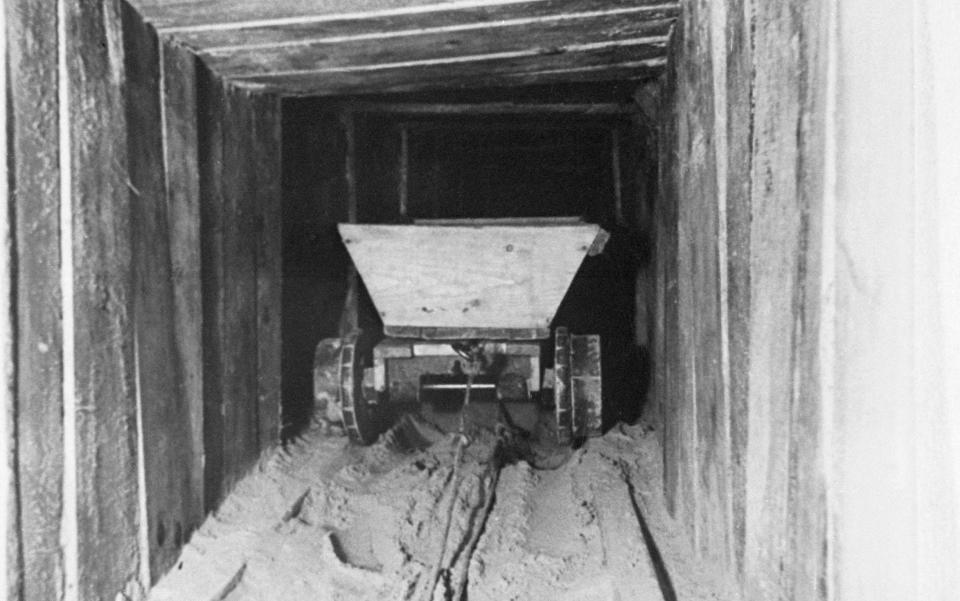

The actual digging itself is accurately portrayed. As described by Bartlett, Harry was dug 30ft down and more than 300ft in length (actually 344ft) from the hut in the north compound and into the surrounding forest (Harry went from hut 104, not 105 as seen in the film). In reality, the “trap” (or entrance) for Harry was set under the stove; in the film, it’s under the washroom drain. This was actually the trap for Dick. The drain, however, was an inventive idea and worth showing in the movie: it could be resealed and filled with water, so diggers could stay underground and avoid detection while the drain worked as normal.

The engineering of Harry is close to the real thing, too, with slats from the POWs’ beds used to support the tunnel (indeed, the Kriegies slept uncomfortably), makeshift air pumps, and wheeled trollies. There were also “halfway house” spaces – resting points along the tunnel – nicknamed “Piccadilly” and “Leicester Square”. The techniques were borrowed from other POW escapes.

What isn’t portrayed – understandably for a 1963 war picture – is that due to the sweat and muck, the diggers worked naked. With poor diets and dodgy constitutions, they had to dig through each other’s excrement. “It was no joke when someone had a dicky tum down there in the tunnel,” explained Ken Rees, a Welsh wing commander.

In the film, members of X Organisation disperse the tunnel dirt by wearing little bags hidden under their trousers, which release the dirt out of the bottom of the leg and onto the ground. This was one of several methods used. Other POWS devised a system of wearing two trousers, with dirt packed into the inner trousers and released onto the ground, or stuffed it in rolled-up towels then thrown out when they unfurled the towels for a spot of sunbathing. As Walters details, they made an estimated 18,000 dispersal trips. In fact, there was so much sand in the Kriegies’ gardens that the German guards began searching for possible tunnels.

Also seen in the film is X Organisation’s system of deceiving the guards – almost a production line of distractions, secret signals, and cover stories. “If a German appeared at one part in the camp,” says Walters, “within ten seconds the guys in the tunnel would know about it through a system of re-laid messages.” Even some of the escapers didn’t know the exact location of Harry until the actual night.

Something omitted from the film is the fact that only about a third of prisoners at Stalag Luft III wanted to escape. “Two thirds had the attitude of ‘I’ve done my bit, I’m safe behind this barbed wire, I don’t want to get in a plane again,’” says Walters. “You have to remember – nearly every man in that camp had been in a plane crash. Getting in a plane again was a terrifying prospect. They’d seen their friends plummet to their death. They’d seen people burn alive in cockpits.”

It’s not quite in the do-or-die spirit of the film, which plays out like a jolly old caper as they amass forged papers, disguises, maps, and other items. The real X Organisation modified uniforms, towels, sheets, and clothes sent via the Red Cross. They also forged documents, and made a printing press with jelly. But not all of it was up to scratch. The passes didn’t stand up to inspection, which led to some of the Great Escapers being recaptured while on the run.

The film also underplays the German assistance. Walters calls the real escape “the greatest Anglo-German cooperation since the marriage of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert”. In the film, James Garner’s charismatic scrounger bribes a gullible guard, Werner (Robert Graf), to procure key items. Certainly, members of X Organisation – who were well stocked with Red Cross-sent goodies – used bribery and blackmail. “Some Germans had two cigarettes a day, the POWs had 10,” says Walters. “If you’re five times richer than your guards, that’s going to happen.”

Other German guards, some of whom were anti-Nazi, helped willingly by supplying the Kriegies with goods and intelligence. “There were Germans who got their wives to type up false documents,” says Walters.

Production of the film – like the real Great Escape – was blighted by bad weather, one of several reasons that its budget escalated from just over $2 million to $4 million. There was another problem: Steve McQueen.

Six weeks into production, Sturges screened dailies footage for the cast. According to Donald Pleasence (who thought the film looked like a turkey) McQueen stormed out. He was unhappy with his role and demanded rewrites. McQueen was especially irked by co-star James Garner for nabbing the best material and coming across as a bigger star. McQueen went AWOL and refused to return to production.

Garner and James Coburn (playing an Aussie POW) met with McQueen to discuss how they could beef up the Hilts character. But McQueen turned down every idea. “Steve wanted to be the hero but he didn’t want to do anything heroic,” recalled Garner. Sturges threatened to write McQueen out of the film entirely and McQueen called in his agents. They brought in a writer to work on McQueen’s scenes. The character was a loner, that was the point – sat in solitary, throwing a ball against the wall, and saying “I wouldn’t do that for my own mother” when the Brits ask him to help. But script rewrites made him an integral part of the operation.

McQueen also caused trouble on the Munich roads. Reports on McQueen’s high-speed hi-jinks vary. McQueen biographer Marc Eliot details how the actor received 37 tickets and wrapped a car around a tree. Actor Tom Adams went further and claimed McQueen “wrote off six or seven cars out there”. Other actors were reported to be speeding along the Munich roads too – but McQueen was the fastest. “We have stopped a lot of your friends this morning, Herr McQueen,” said a policeman in one amusing story. “But I must tell you, you have won the prize.”

According to Eliot’s biography, the film studio lawyers had to work overtime to keep McQueen out of jail. They resorted to telling German officials that if McQueen was locked up, production would stop – which meant no money for the local economy.

McQueen wasn’t the only actor causing behind-the-scenes drama. As detailed in Glenn Lovell’s Escape Artist, Charles Bronson began an affair with Jill Ireland, the wife of co-star David McCallum. Ireland had suffered a miscarriage while McCallum was back in London. Assistant director John Flynn described how Bronson sat by her bedside and “was on her like an animal” as soon as she recuperated.

The real Great Escape took place on the night of March 24 and 25 1944. In the film’s recreation, it’s a balmy evening. In reality, the conditions were “bloody freezing”, says Walters. “The prisoners escaped wearing hopelessly ill-suited clothes for tramping around in snow, ice, freezing mud, slush, muck, you name it.”

In the film, McQueen pops his head out of the tunnel and discovers they’re 20ft short of the forest, leaving them exposed to the nearby watchtowers as they clamber out. That really did happen – a detail given some dramatic spin in Brickhill’s book and embellished in subsequent retellings. “It doesn’t seem to have been an enormous problem at the time,” says Walters. “They were still a significant distance from the guard tower and there was snow on the ground.”

In the movie’s retelling, there’s a stroke of luck when an air raid forces all the lights out, allowing a number of POWs to escape out of the tunnel under the cover of darkness. There was indeed an air raid, but the blackout caused problems for the escapees trying to find their way through the trees – some of them got lost. It created problems inside the tunnel too, which was plunged into darkness.

There were also collapses, caused by too many escapees trying to squeeze through. Others panicked and forgot to send the cart back and pull the next man through, creating more delays and chaos. Two-hundred men had been selected to escape, but only 76 made it out. “Within 24 hours, most of them had given up or been recaptured,” says Walters. “They were understandably but hopelessly ill-prepared.”

The film’s post-escape scenes are the most fantastical. In their efforts to flee the country, the disguised POWs are seen jumping from a train, stealing a plane, and – of course – trying to leap over the German-Swiss border on a stolen motorcycle.

The motorcycle chase, entirely fictional, was added at McQueen’s suggestion – a way to show off his skills and, most likely, a means of placating his fragile star ego. But McQueen wasn’t allowed to perform the iconic leap himself. Instead, McQueen’s pal (and stuntman) Bud Ekins performed both the jump and slide into barbed wire, a manoeuvre that sees Hilts recaptured.

Robert Relyea, however, recalled that McQueen and Tim Gibbes, a motocross rider brought in for some of the bike stunts, also performed the jump on camera. Though Ekins performs the jump in the film, Relyea claimed it could have been any of them. McQueen – who was a better motorcyclist than the German stuntmen – also played a Nazi soldier in the sequence, so he’s effectively chasing himself on motorcycle.

Incredibly, Relyea performed the film’s most dangerous stunt himself, which comes when Garner and Pleasence crash a stolen plane (another fictional detail) into a field, cutting one of its wings clean off. Relyea, who had a pilot’s licence, got in the cockpit for the crash. The impact knocked him out cold and left him with injuries.

One of the film’s best-known moments comes shortly after, when Bartlett and Mac (Gordon Jackson) are recaptured after a slip of the English tongue. They try to board a bus while posing as Frenchmen, but a Gestapo officer tricks Mac into speaking English. “Good luck,” says the Nazi, to which Mac replies “thank you”. The scene is based on something that may have happened. According to a report by a Gestapo officer, Roger Bushell and his travelling partner, a Frenchman named Scheidhauer, were arrested when one of them answered “yes” instead of “oui”. If it did happen, says Walters, it seems plausible that Bushell made the mistake. “Of those two men, who’s more likely to answer in English?” asks Walters.

In the film, the three men who escape to freedom are an Australian, Brit, and Pole – the characters played by James Coburn, John Leyton, and Charles Bronson. In reality, the three successful escapees were Norwegian, Jens Müller and Per Bergsland, and Dutch, Bram Vanderstok.

If it’s the tone of The Great Escape that’s wrong, it’s best encapsulated in the climax as Bartlett and other recaptured POWs are rounded up and driven (supposedly) back to camp. Given a moment to stretch their legs, Bartlett declares that the tunnel digging “kept me alive” and “I’ve never been happier”. At that point, they’re gunned down. But it’s still triumphant. It’s their defiance in the face of evil that really matters.

The real killings were even more chilling. After Hitler gave the order to have most of the escapers killed, the head of the Kripo went through the names of the recaptured men and decided which of them would be killed. Gestapo officers then drove the recaptured men away in pairs or small groups – under the pretence that they were being transported back to the camp. They were offered a pee break along the way, or led into a field, at which point the Gestapo shot them from behind. False statements were then made and the bodies were cremated. “Bushell was shot in that way,” says Walters. “And he was shot badly. He was writhing on the ground and had to be shot again. It’s incredibly undignified – it’s repellent, it’s horrific. Had the film had ended like that, people would have left the cinema feeling different.”

The Great Escape – which premiered in London on June 20 1963 – has mythologised the events. The film – even just the tear-in-the-eye theme – is imbued with a stirring, rousing magnificence.

For Guy Walters, the events stick in the memory because of the grisly end. Indeed, there were other escapes that are less well remembered. He points to a breakout of 65 POWs from Oflag VIIB in Eichst?tt in June 1943. “There were other great escapes from other camps,” Walters says. “There were greater escapes than the Great Escape. Why are we interested in this one? Ultimately, The Great Escape is a murder story. The escape is not unique. The murder is unique.”

Guy Walters is leading tours at the sites of Stalag Luft III and Colditz in October. See here for more information