Stephen Street on falling out with Morrissey, the Britpop wars and getting Pete Doherty to behave

Stephen Street must have the patience of a saint. Over the last 35 years, he has become the go-to producer for some of music’s most demanding, damaged and downright difficult stars, coaxing career-defining albums from The Smiths, Blur, The Cranberries and Pete Doherty. He has never headlined Wembley or been stopped in the street by fans, but you almost certainly own one of his records.

“I don’t take any nonsense,” he says, speaking (via Zoom) from a home office piled high with CDs and cassettes. “We’re in the studio to do a job. It’s the artist’s money we’re spending and we have to deliver as good a record as possible.”

Straight-talking and considered, the 60-year old Londoner owes his career to this same sensible streak. He turned to music production in the early 1980s after realising that his band, the ska-pop act BIM, were going nowhere despite signing a record deal. Faced with the prospect of years touring the country in a Transit, Stephen decided there had to be a better way.

“I wrote to all the studios, and finally got a job as an assistant engineer at Fallout Shelter Studio at Island Records. It was there [that] I had my first big break, when The Smiths came in to record Heaven Knows I’m Miserable Now. By then, they’d already been on Top of the Pops and I thought they were incredible. I went out of my way to try impress them and at the end of that session, they took my name and number.”

He went on to engineer The Smiths’ next two albums, Meat is Murder and The Queen is Dead, before taking over as producer on the band’s fourth and final record, Strangeways, Here We Come. By this time, ardent Smiths fans knew him as the band’s unofficial fifth member, capable of teasing magic from their formidable frontman Morrissey and exacting guitarist Johnny Marr.

“I learned a lot about man-management,” he says. “Morrissey is quite a demanding character, but I realised quite quickly that you don’t just focus on the lead singer. They were all incredibly hard-working, and the best bands are strong all the way through. The singer can have a hissy fit if he wants, but I make sure every single person is involved.”

The strategy paid off, and the sessions for Strangeways were fun, Street says. Everyone got on well and the band made their bravest and most ambitious album so far. Yet by the time Strangeways was released in September 1987, The Smiths had already announced their split.

“I never in my wildest dreams thought it was all over,” Street says. “I really thought it was just a little tiff and they’d be back together in a couple of months. [But] it was hard for Morrissey to stick with a manager, and bands need a good manager. Johnny wanted one, and he didn’t want to get rid of the manager they’d just found. The tension was there because the business in the background wasn’t getting sorted.”

Any chance of a reunion was finally destroyed two years later, when The Smiths’ drummer Mike Joyce and bassist Andy Rourke started legal action against Morrissey and Marr for an equal share of the band’s profits. Though Rourke settled out of court, the High Court eventually ruled in Joyce’s favour, asserting he was entitled to a 25 per cent share of the band’s earnings, rather than the 10 per cent he had been paid.

“That killed it,” Street says. “I think Johnny and Morrissey got that wrong because Mike and Andy were very important. They were certainly more than pieces of a lawnmower, as they were referred to in court. If they hadn’t gone through that, they probably would have reformed at some point. Too much had been said and too much damage had been done by then.”

Still, Street’s own relationship with Morrissey endured, and he co-wrote and produced the singer’s acclaimed debut album Viva Hate, released just five months after Strangeways. The pressure almost gave him a stomach ulcer.

“Towards the end, I couldn’t get out of bed. I had terrible stomach cramps caused by stress. Morrissey could do no wrong at that time, so if the record flopped, I would have been blamed,” he says. “I was producing, engineering, playing on it and trying to keep one step ahead of Morrissey’s whims and desires.

“I mean, people think he’s miserable and he’s not. He’s got an incredibly wicked sense of humour. But sometimes the darkness can descend and everything closes down, so you have to read the signals.”

It was the last album the pair would make together. Street argued that he should be due a greater share of profits if they continued working together and both parties called in the lawyers. Morrissey eventually returned the torn pieces of one solicitor’s letter to Street with a note declaring simply: “Enough is too much.” Since then, there has been the odd e-mail, a friendly meeting at Claridge’s a decade ago, then another falling out about the remastering of Viva Hate in 2012.

“I dared to criticise so I was incommunicado again,” Street says like a man who has seen it all before. “Occasionally there’ll be an e-mail. I’ll reply, then six months later, that e-mail address is gone.”

Stephen’s musical Midas touch ensures that other bands always return his call. Since Viva Hate, he has worked his magic on The Pretenders, Catatonia, The Psychedelic Furs, Kaiser Chiefs, New Order and The Cranberries. Following singer Dolores O’Riordan’s tragic death, he returned to work with the latter band one final time to produce last year’s release In The End, using O’Riordan’s posthumous vocals.

“God bless her, she had her demons, but she had the voice of an angel. She was only 19 when I first met her and she wouldn’t work unless her boyfriend came to the studio. That’s something I stamped out straight away.

“She didn’t mix too well with drink unfortunately, but I really enjoyed working with her. Most of the time I was in the studio with her, she was as good as gold.”

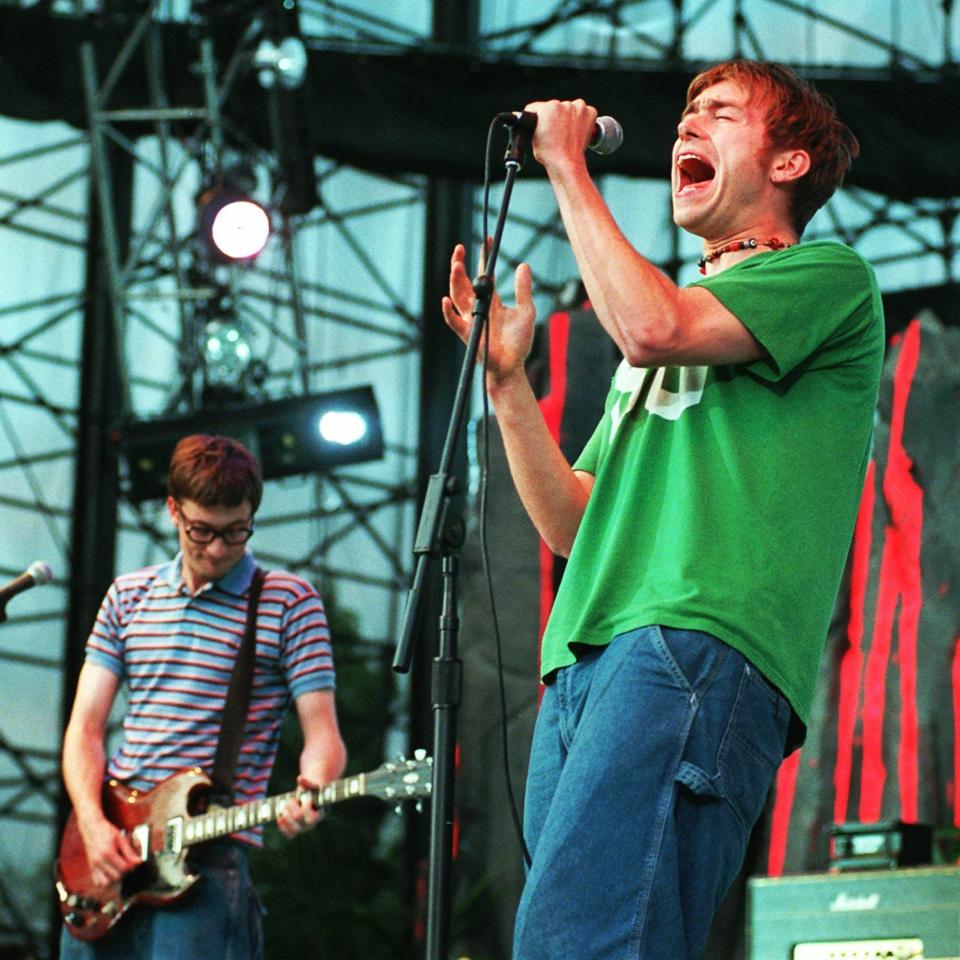

But it’s Street’s work with Blur that remains his best known. He produced the band’s first five albums, including Parklife, which became the defining record of the Britpop era. “I’m very proud of it,” Street says. “It was a really exciting time. Later on, the Blur and Oasis thing got a bit nasty, especially some of the things coming from their [Oasis’s] side. I thought they were a little below-the-belt.”

The biggest challenge through it all, however, was keeping the party out of the studio.

“I would tell band members, ‘I want you in the studio at 10am, because I want to be done by 9pm.’ A lot of bands think the studio is their time to party, but it’s not. It’s time to work.

“Damon [Albarn, Blur frontman] has said he learnt his work ethic from me, and he’s one of the hardest working people in the business. The guy is a machine. A lot of people find him too much or overbearing, but he’s a lovely bloke. I think of him like a brother.”

Inevitably, Britpop mania eventually took its toll on Blur. By the time they came to record their fifth self-titled album, the band needed Street more than ever.

“They were not in a good state,” he says. “Graham [Coxon] wasn’t talking to the rest of them. One of the first things Damon asked me to do was go to Graham’s place in Camden and convince him we could make a record. That’s now my favourite album [of those] I’ve done. And it was enough to save Blur.”

Yet Stephen’s greatest challenge was still to come. In 2007, he produced Babyshambles’ second album Shotter’s Nation, followed by their controversial frontman Pete Doherty’s debut solo record, Grace/Wastelands, two years later.

“I didn’t fully appreciate what a challenge it would be,” Street admits. “I can say this because it’s well-documented, but Pete really is the only junkie I’ve ever worked with. Everyone thinks all musicians are junkies but they’re not. I felt I had to try and get through to this guy.

“He had the Kate Moss circle around him, and I didn’t want anything to do with that. When those people turned up, I’d call it a night. I did not want to sit there while they did God knows what. I had to read him the riot act a few times – but I’m very proud of what I’ve done with him. I love him and I worry about him, and I know he’d hate to hear me say that. But he’s up there with Morrissey as one of the greatest poets I’ve worked with.”

He pauses, choosing his words with the same thoughtful precision so many bands have needed to rely on when it really mattered.

“The thing about truly great artists is they inspire you to do really good work too. Damon, Pete and Morrissey are very different people, and very demanding in their own different ways to work with – but they’re geniuses. I don’t use that word often, but they really are.”

Bradford’s new album, Bright Hours, produced by Stephen Street, will be released in February and is available to pre-order here