Steph & Ayesha Curry Are Playing the Long Game

Something is missing—a few things, actually—when the Eat Learn Play Foundation hosts its third annual summer fun day for the children of Oakland, California. As the event begins, on a late July morning in the Fruitvale section of the city, the organization’s founders, Stephen and Ayesha Curry, alternately wield paintbrushes and drills as they labor in the heat alongside volunteers to finish building a playground. The place was designed by the kids who will use it, and it includes slides, jungle gyms, monkey bars, and brightly patterned walls—but there’s not a single step-and-repeat carpet, self-congratulatory commemorative plaque, or statue in sight.

When the daylong festivities continue, a few miles south at the Oakland–Alameda County Coliseum, Steph and Ayesha sit in the outfield with 1,200 kids, high-fiving and passing popcorn, as the hometown A’s play the Houston Astros. After the game Stephen mingles with the kids on the field, joining them in race after race around the basepaths. There are selfies with the kids and autographs signed, but no speeches, no awards, no silent auctions or capital campaigns—just a backpack full of books for each kid, which the NBA superstar helps hand out. There are a couple of pitches, but they are aimed not at donors but at home plate—Ayesha’s ceremonial first pitch floats to the batter’s box, while Steph’s sails wide and nearly hits the photographers. The wild pitch is a mistake; the omission of fanfare is not. As the Silicon Valley saying goes, it’s not a bug—it’s a feature.

“Impact, not legacy.” The greatest three-point shooter in -history needs just three words to explain the principle that governs his work off the court. “We always talk about making it about the work,” Stephen says. “It’s bigger than just us, bigger than our names.”

Although he is an increasingly vocal advocate for voting rights and racial equality, he is specifically referring to Eat Learn Play. Since its founding in 2019, ELP has helped thousands of children in Oakland, building playgrounds and schoolyards across the city, giving away more than 500,000 books, and helping to distribute more than 25 million meals and 2 million pounds of produce. It has brought in partners like World Central Kitchen, No Kid Hungry, and Kaboom! and gotten corporate support from such companies as Workday, Rakuten, Kaiser Permanente, and Under Armour (the last of which is reportedly negotiating a lifetime contract with Curry worth more than $1 billion). When it comes to fundraising, Stephen and Ayesha don’t put on the hard sell. “I’ll never twist an arm,” Ayesha says. Instead they build a coalition of willing partners by showcasing facts and statistics. Some are startling: Nationwide, only one in three third graders is reading at grade level, while only 15.4 percent of Black and 12.5 percent of Latino elementary schoolers in Oakland read at grade level. “When you have passion about something, there’s a natural gravitational pull,” Steph says. “The mission does sell itself.”

“Unlike a lot of prominent folks lending their voices, -Stephen and Ayesha really see and appreciate the interconnection between hunger, education, and kids’ health,” says Billy Shore, the founder of Share Our Strength, which oversees the No Kid Hungry campaign. “And that’s a huge, huge leap. I say this having done this work for a long time. Until you see that connection, you’re pushing a rock up a hill that will keep sliding back down on you.”

It’s two days before the summer fun day, and Steph is sitting on a sofa, a sticker-covered MacBook Pro open on his knees. Dressed in a navy polo buttoned to the top, designer track pants, and a black pair of shoes from his Under Armour line, the 34-year-old Golden State Warrior is sending emails and reading updates, catching up on administrative work ahead of the foundation’s anniversary event. Last spring he graduated from Davidson College with a degree in sociology (his thesis was on gender equality in sports), fulfilling a promise he made in 2009, when he declared for the NBA draft following his junior season. Now, barely a month after winning his fourth title and first NBA Finals MVP, thrusting his name into the GOAT conversation, this is how Stephen Curry spends his time.

After a few minutes Ayesha joins him on the sofa. A TV personality, cookbook author, restaurateur, actress, and influencer, the 33-year-old is a celebrity in her own right. The couple, who first met in church as teenagers, set out to create a foundation that harnessed their passions. “We knew our heart lay within the community,” Ayesha says. “When it came to what we wanted to advocate for, for him, that was always education and being active. For me it was always food and childhood hunger.”

Hence the name Eat Learn Play. It was short, descriptive, and memorable—and they didn’t want something like the Stephen and Ayesha Curry Foundation. (Though that’s exactly what their business managers initially registered when applying for nonprofit status. The mistaken assumption was “discussed.”) Ayesha has always been wary of programs that exalt donors as saviors. “That kind of help is very self-validating for a lot of people,” she says. “We don’t want to encourage that. It wasn’t goal one or even one thousand.”

Although they didn’t create a foundation in their name, the Currys have made ELP in their image. “The two words most often associated with Ayesha and Stephen are joy and authenticity,” says Chris Helfrich, CEO and the first hire the Currys made at ELP. “It’s critical for us to keep those things in everything that Eat Learn Play strives to do.”

ELP’s name, too, contains a reminder to stay grounded. “The fact that play is in the title of the foundation,” Steph says. “We don’t want to be pretentious or unapproachable. We want to meet people where they are. Those are the soundbites, but you have to live that, bear it out in everything you do. Bring joy, respect everybody’s dignity. We have to be very intentional in that.” Part of their goal is to remove the negative connotations of assistance programs. “There’s such a stigma attached to it,” Ayesha says. “Nobody wants to say they’re getting a handout, whether you’re a child or an adult. So, for us, we want to make it feel fun. We wanted to make it feel like it was just a part of the community, just something that’s there. If you need it, you need it. If you don’t, still come say hi. Reducing the stigma really helps with our efforts.”

“Like the bus,” Steph adds, “being able to turn it into the educational ice cream truck.” The vehicle he is describing is a retrofitted school bus wrapped in a colorful street art mural that functions as a food bank and lending library on wheels. It’s also outfitted with a roof deck, sound system, and, of course, a backboard and hoop.

Ayesha smiles and says, “We’re like the Montessori of nonprofits.”

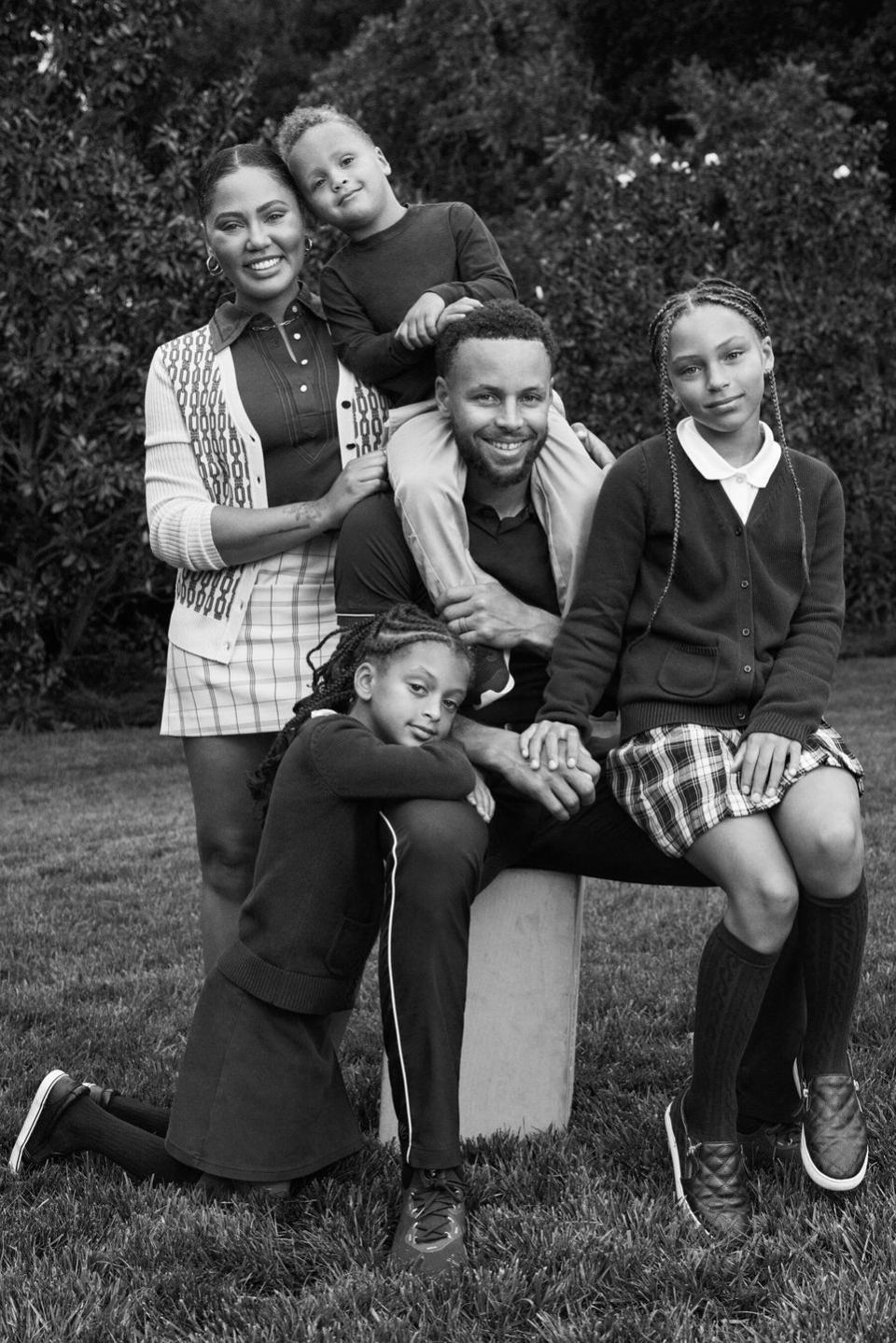

Stephen and Ayesha have no shortage of influential friends and informal advisers. They count Vice President Kamala Harris and Barack and Michelle Obama as friends. The first phone call Steph took after hoisting the championship trophy in June, his jersey still soaked with champagne, was a congratulatory call from his buddy the former president. As a superstar with global reach, Stephen could have attempted global impact, too. He chose instead to go deep where he and Ayesha had roots, in Oakland. It’s not coincidental that they launched ELP in 2019, when, after 47 seasons in Oakland, the Warriors decamped across the bay to far more affluent and less diverse San Francisco. Stephen and Ayesha wanted to affirm their connection to Oakland, their hometown of 13 years and the place where they started their family, becoming parents to daughters Riley and Ryan and son Canon. “This is a community that supports us,” Steph says. “This was where we wanted to plant our flag and where we want our goals to be realized.”

That community focus was crucial in attracting a member of Obama’s cabinet, Arne Duncan, the former secretary of education, to join the ELP board. “They could have done something nationally to start. They could have done something internationally, but they started locally,” Duncan says. “If they can accomplish the kind of things they want to do—really raising reading levels in the community, giving kids a chance at life, helping them build healthy lifestyles—if they can do those things, is that a model that’s replicable in other cities? Absolutely. Is that a model that’s replicable nationally and internationally? Absolutely. It’s not there yet. But the laser focus on one community rather than spreading themselves thin is hugely important. It’s really about the work. It’s not the Steph and Ayesha show.”

Stephen’s commitment to service started close to home. Growing up, he volunteered at the computer literacy program for disadvantaged youth in Charlotte, North Carolina, started by his father, NBA player Dell Curry. (Dell played 10 of his 16 NBA seasons in Charlotte.) Early in his pro career, -Stephen toured refugee camps in northern Tanzania that were home to displaced people from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, a trip organized by Helfrich. That mission for the UN Nothing But Nets program was important for him, so much so that he missed his wedding anniversary and left Ayesha with three-week-old Riley to see the living conditions and the health clinics, where he witnessed the scourge of malaria up close. “It moved me,” Steph says, getting choked up at the memory, “and made me see that even small changes can have this outsize impact.” Distributing $5 mosquito nets has saved 7 million lives in Africa since 2000. “We want to cure malaria, but we can also do these simple things to stop its spread,” he continues. “You can spend billions chasing a cure, great, but for so little you can save lives now.” The emphasis on making an immediate difference helped shape his approach to philanthropy.

Ayesha grew up in Toronto, where she would join her parents in preparing hot meals on holidays and bringing them, along with blankets and clothing, to the homeless. When the pandemic struck, she leveraged her International Smoke restaurants to distribute meals to the disadvantaged. Later she found herself on the phone lobbying Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi about the need to extend school lunch programs even as schools were locked down. A funding bill was passed with $8 billion in federal nutrition assistance. Then in April of last year she testified virtually before the House Committee on Rules and the Congressional Hunger Caucus to help close the childhood food gap, exhorting representatives, “We all need to be kid-partisan.”

The couple have already managed to pass on their ethos. Riley, 10, spent most of her summer break creating a cookbook with her best friend, with the goal of donating the proceeds to ELP. “I love the direction that her heart is flowing,” Ayesha says. “It’s been really great to witness as her parents.”

Stephen and Ayesha have heard the skepticism about them trying to save the world. “I saw this quote that said, basically, beware anybody who says they’re trying to save the world,” Ayesha says. “We’re definitely not trying to do that. We’re trying to help push our community forward. Then we can talk about other places.”

“That’s true. First you crawl,” Stephen says. The work in Oakland is far from done. “We want to make sure that we’re sticking to our word and making the most impact where we vowed to make the impact first,” Ayesha adds. But Steph points out that while their work is innovative, it’s also non-proprietary, a tranche of open-source solutions that other communities could adopt and adapt.

The inquiries have flowed in, according to Helfrich, and they are seeing their model crop up elsewhere. As much as the Currys and ELP are invested in Oakland, they refuse to remain static. They’re building brand partnerships and investment opportunities, and storytelling opportunities through Unanimous Media, their production company, which signed a partnership agreement with NBC Universal last year.

“There’s momentum, even if we were not front and center, and that’s the beauty and the high ceiling of all this,” Steph says. “All these things are starting to become much more cohesive. That will then set up a very, very long runway even when basketball stops.”

Showing no sign of decline, and with four years remaining on his contract, Stephen’s retirement from the NBA isn’t imminent, but as he and Ayesha work with Helfrich on a three-to-five-year expansion plan, they are already preparing for it. Duncan and others believe that is when we’ll witness the -Currys’ greatest impact and see them change the social sphere much as Stephen has transformed the game of basketball.

Stephen rubs his chin and smiles at the prospect. “When the ball stops bouncing, the work won’t stop,” he says. “It’s just getting started, right?”

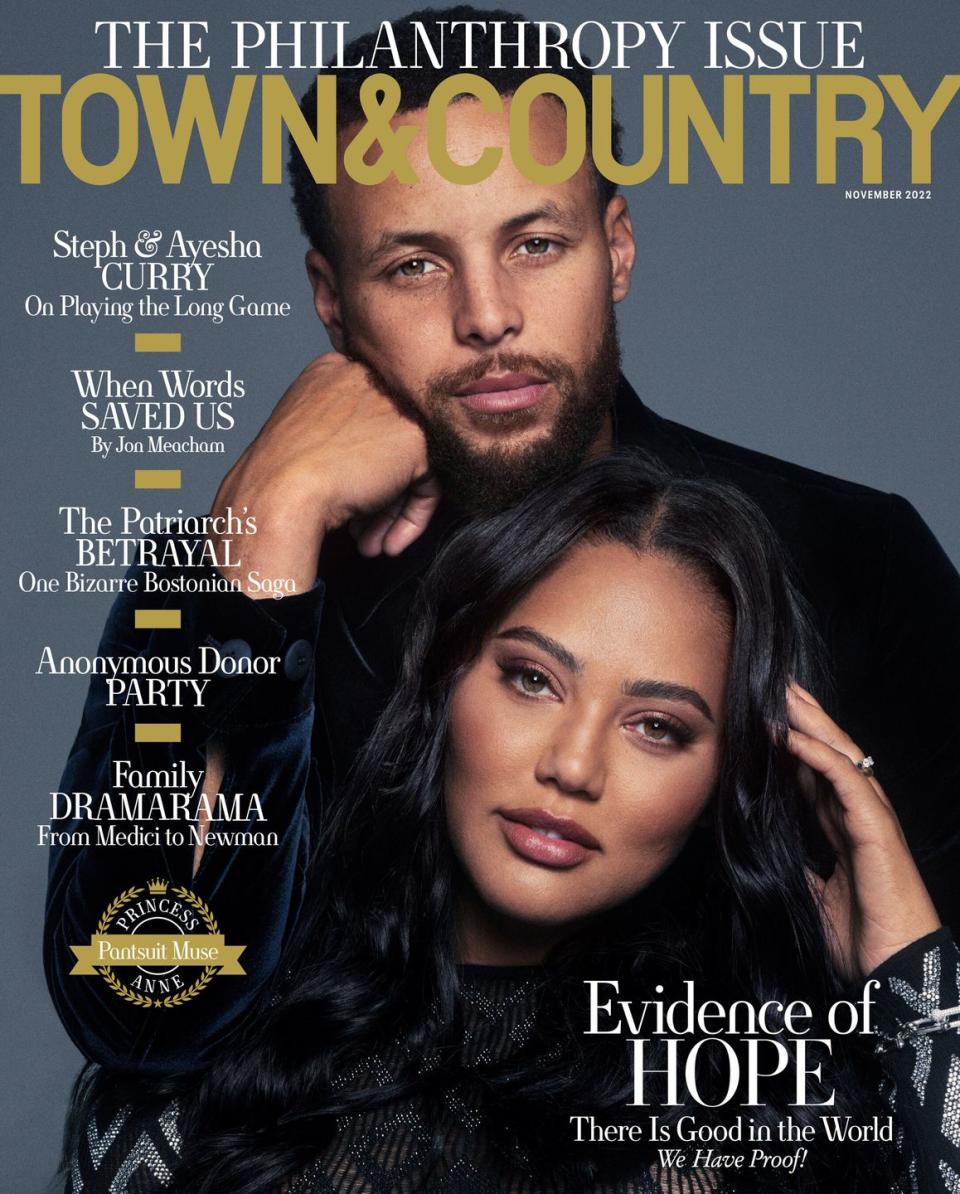

On Ayesha: Giorgio Armani sweater ($7,400). On Stephen: Giorgio Armani jacket ($3,595).

Photographs by Michael Schwartz

Styled By Jason Bolden

Hair by Sonia Cosey. Makeup by Ashley Bias (Ayesha). Grooming by Yusef (Stephen). Production by ViewfindersLA.

This story appears in the November 2022 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE NOW

You Might Also Like