The Stan effect: did Eminem’s song about a crazed fan just make fans crazier?

“Summertime sadness” has just taken on an entirely new meaning for Lana Del Rey. The Video Games singer put out a lengthy Instagram post this week in which she lashed out at her detractors (“lengthy” in that it reads like a Gettysburg Address for influencers). That was the intention, at least. In reality, she opened the gates of social-media hell by appearing to hit out at a panoply of fellow pop stars.

“Now that Doja Cat, Ariana [Grande], Camila [Cabello], Cardi B, Kehlani and Nicki Minaj and Beyoncé have had number ones with songs about being sexy, wearing no clothes, f---ing, cheating, etc – can I please go back to singing about being embodied, feeling beautiful by being in love even if the relationship is not perfect?”

Del Rey was protesting her portrayal in the media as a submissive songwriter – a tag that has flowed from lyrics such as “He hit me and it felt like a kiss” and “He hurt me but it felt like true love”. She intended her Instagram message to read as a strong statement from a woman who wasn’t taking it any more. Instead, it was received as a broadside against some of pop’s most prominent black and ethnic minority stars.

And because this is the internet, the land that nuance forget, hardcore fans of the aforementioned artists were quick to disapprove. Suddenly it was as if the entire world wide web were piling onto Del Rey. (She later amended her post to explain she had singled out Beyonce and the gang because they were her “favourites”.) And in much of the coverage, diehard devotees of these stars have been described as “stans”.

“Stan”, as defined by the Oxford English Dictionary, is “an overzealous or obsessive fan of a particular celebrity”. For instance, “he has millions of stans who are obsessed with him”. You can also use it as a verb: you might “stan” Lana Del Rey or, over the past several days, you might not.

“Stanning” has become a full time crusade for many, and is one of the higher-profile manifestations of the toxic side of online discourse. Weirdly, the lighter the music the more unrelenting the stans. Metallica, for instance, don’t have many fans in this category. But featherweight South Korean pop sensations BTS unquestionably do: last year the Capital FM DJ and former I’m A Celebrity contestant Roman Kemp was reported to Ofcom by BTS fans for supposed race discrimination after calling their music “noise”.

Then there's comedian Pete Davidson, who felt the wrath of Ariana Grande "stans" when their relationship ended. “I feel I need to remind my fans to please be gentler with others,” Grande stated on Instagram. “I really don’t endorse anything but forgiveness and positivity. I care deeply about Pete and his health. I’m asking you to please be gentler with others, even on the internet.”

Stan love can sometimes feel like tribal warfare. You’ll find Lady Gaga fans charging into virtual battle with Cardi B lovers, or Taylor Swift’s legion of “Swifties” defending her honour against whoever has incurred her wrath (not that Swift approves of, or instigates, these onslaughts). The world is complicated, but when you’re stanning your favourite star, it can feel very comfortingly simple.

Del Rey’s timing is certainly on the money. Her Instagram post arrived in the very week that the song which originally catalysed the idea of a “stan” turns 20. The track changed how we speak – and it also changed the genre of rap music. Ironically, modern stans often don’t know where the term originated – or the fact that it was intended as a critique for overzealous fandom.

Twenty-first-century hip-hop’s first moment of true greatness had begun with Gwyneth Paltrow missing her train. In the 1998 rom-com Sliding Doors, Paltrow plays a London PR executive whose future takes a turn for the unexpected when she sees her carriage taking off as she’s sprinting down the steps at Embankment tube station.

Life likewise veered off at an unexpected trajectory for Bronx producer Mark Howard James. He was watching Sliding Doors at home when he heard a snippet of music that changed everything for him. “My tea’s gone cold, I’m wondering why I / got out of bed at all,” cooed Dido Florian Cloud de Bounevialle O’Malley Armstrong on the soundtrack. “The morning rain clouds up my window / and I can’t see at all.”

Dido was an obscure artist singing an even more obscure song, Thank You. But when James, a creator of block- rocking beats under the alias The 45 King heard it, his world stopped in its tracks. He switched off the film and ran downstairs to his studio.

“I looped it,” he recalled. “Added a bassline.” And then he sent it to his contacts at Interscope Records in Los Angeles. From there it made its way to Detroit, where a one-time burger stall cook and rapper previously known as MC Double M was toiling over his new record – a project that finally saw daylight 20 years ago this week.

He slapped on the 45 King’s loop of Thank You. And when Dido got to the line “put your picture on my wall… It reminds me that it's not so bad, it's not so bad” he had an epiphany.

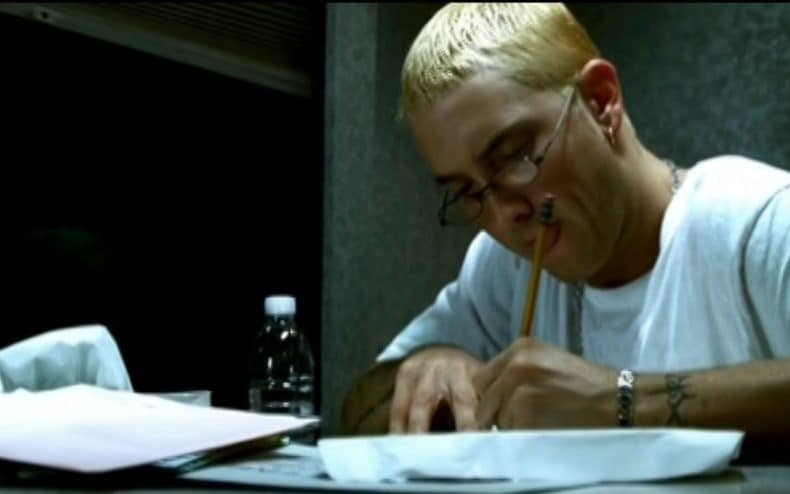

“Seeing the vision in what Dido was saying – ‘picture on my wall’… this is about an obsessed fan,” said the former MC Double M, who was having slightly more success under his new alias of Eminem

Eminem was an anomaly in the hip-hop scene at the time. On the Detroit rap circuit, the artist (born Marshall Mathers in 1972) was perceived as an outsider because he was white. And even after the success of his 1999 major label debut, The Slim Shady LP, question marks lingered.

Eminem could clearly raise a ruckus. Sweary smashes such as My Name Is and ’97 Bonnie & Clyde – in which Eminem fantasises about dumping the body of his future wife in a lake – attested to his skill at poking a finger in the eye of the moral majority.

And yet as he set to work on a follow-up album it was not entirely clear if he was a rhymer for all seasons or merely a potty-mouthed novelty. Once the shock value eroded – would he still have a career?

Stan was the song into which Mathers poured all his rage and insecurity, while wrestling with fame and its many downsides. It’s an account of a crazed fan who writes increasingly deranged letters to Mathers and then kills himself and his own pregnant wife. It’s dark, but at its centre is the deeply moral argument that we shouldn’t put famous people on a pedestal and certainly ought not build our lives around them.

This was a subject about which Mathers had come to have strong feelings. Eminem grew up poor and on the margins of society, and from early adolescence dreamed only of being a rapper. But he had never craved wealth and fame. When it came, he was baffled by it.

Stan was a standout on the Marshall Mathers LP, released on May 23 2000. But its impact has transcended music. Today you can “stan” the Kardashians, Jürgen Klopp and Charli XCX. (Though if you’re no longer a teenager, you really shouldn’t.) Three years ago, the Oxford English Dictionary bowed to the inevitable and accepted that “stan” is now officially a word. In 2019 Merriam-Webster followed suit. To “stan”, it said, was “to exhibit fandom to an extreme or excessive degree”.

Eminem wasn’t talking about fame in the abstract. Celebrity was something he could feel pressing in from all around, clammy and asphyxiating. “I wish I could come off-stage and turn off the lights that flash over my head saying Slim Shady and Eminem,” the rapper had told Muzik magazine in 2000. “I wanna turn that s--- off and just be Marshall Mathers again.”

However, as he began to toil on 2000’s Marshall Mathers LP, he was agonisingly aware that he could fall as quickly as he had risen. One minute you’re the world’s favourite rapper, mentored by Dr Dre and with influential record executive Jimmy Iovine in your corner. The next, you might be back in Detroit, plunging towards obscurity.

He was reminded of this when he went finally went home after the megabucks Slim Shady tour. Affixed to the door of the Detroit mobile home that was still his principal residence was an eviction notice. He’d forgotten to pay his rent, and now there was a danger he might end up homeless.

“It worries me,” he confessed to Melody Maker. “To be honest, I think about it a lot, and I’m being really, really careful with my money. I think about the future more than anything.”

He was particularly struck at how differently people treated him once he became successful. He had genuinely come from nothing. Doors were slammed in his face his entire life. Not any more. “Some girl will be telling me how fine I am and trying to sit on my lap and I’ll be thinking, ‘If I was just me and I didn’t have all this fame, you wouldn’t look at me twice. You wouldn’t look at me once.’”

Mathers’s personal woes had, if anything, been accentuated by overnight success. His difficult relationship with his mother had grown ever more strained. She was not amused at his line in the single My Name Is that went “Ninety-nine per cent of my life I was lied to / I just found out my mom does more dope than I do.” Deborah Mathers would eventually sue her son for defamation of character.

Mathers was also continuously feuding with his once-and-future spouse Kim Scott. They had been together since he was 15 and married in 1999 – daughter Hailie was born on Christmas Day of that year – before divorcing in 2001. They remarried in January 2006 only to divorce a second time that April.

All of that was bubbling in the background as he heard Dido singing Thank You. “Stan was one of the few songs that I actually sat down and had everything mapped out for,” he later said. “I knew what it was going to be about”. Working with his regular producers, Larry and Jeff Bass, his starting point was the Dido lyric about a picture on the wall. This he spun into a wrenching tale of paranoia, unrequited devotion and murderous frustration.

Eminem plays two parts in the song. The first rapping voice we hear is his alter-ego of Stanley “Stan” Mitchell, who writes to Eminem claiming to be his biggest fan. Not receiving a reply he grows increasingly vitriolic and deranged.

“I drank a fifth of vodka, you dare me to drive?” Stan exclaims in the third verse, referencing a lyric from My Name Is. Stan is inconsolable that Eminem hasn’t taken the trouble to respond. And now, he explains, he has his pregnant girlfriend bound and gagged in the boot and is about to drive off a bridge.

Eminem rhymes as himself in the final verse. He apologises for his tardiness and says Stan needs help, sharing with him a story about a drunken man who drove off a bridge with his girlfriend tied up. And then the penny drops. “Come to think about, his name was – it was you…”

Stan is grand-guignol pop of the first order. Much of the disturbing imagery – especially the references to a bound and gagged woman – were expunged for the radio single. Even watered down, however, Stan is pedal-to-the-floor gruesome.

The song would become a milestone for Mathers. It went to number one across Europe (though stalling at 51 in the US) And it changed how we speak. “Stan” was embraced by the internet as a noun for uber-fans and as a verb for what they do.

But for all its perceptiveness about the blinding quality of fame in the 21st century, Stan was overshadowed by the many controversies attending the accompanying Marshall Mathers LP.

On the track Kim, a prequel of sorts to Bonnie and Clyde ’97, he screams at his ex-wife and imitates her voice – and then kills her and puts her body in his car. As Red Hot Chili Peppers were to performing with socks on their genitals so Eminem was to stashing bodies in the boot.

He played it to Scott, and suggested she should take it as a compliment. “I know this is a f--ked-up song, but it shows how much I care about you. To even think about you this much. To even put you on a song like this.”

Equally outrageous was I’m Back, with references to the 1999 school shooting that had rocked America. “I take seven kids from Columbine, stand ’em all in line / Add an AK-47, a revolver, a nine/ A MAC-11 and it oughta solve the problem of mine.”

There was an all-too-predictable outcry. In Canada, there were calls to ban Eminem for breaching hate speech laws. At a US Senate hearing Lynne Cheney, wife of Vice-President Dick, characterised Mathers as a misogynist and danger to society.

“He talks about murdering and raping his mother. He talks about choking women slowly so he can hear their screams for a long time. He talks about using OJ’s machete on women, and this is a man who is honoured by the recording industry.”

In the UK, Eminem’s music was banned by the University of Sheffield student union; the university radio station was fined £7,000 for playing one of his songs. And ahead of a three-date British tour in 2001, there were demands that he be barred from entering the country.

There was even a backlash from the Swedish manufacturers of the chainsaw used in the Kill You video (sample lyric: “B---h, I’ma kill you! Like a murder weapon, I’ma conceal you / In a closet with mildew, sheets, pillows and film you”). “We make chainsaws for mature people,” Husqvarna insisted in response. “[Those] with genuine forestry work to do.”

He was ultimately allowed into the UK. Still, the controversy refused to died down. Kicking off the latest leg of the Anger Management Tour in Manchester on February 8, Mathers had the tabloids in a tizzy by appearing to take two ecstasy tablets on stage. However, Eminem took the wind out of their sails of outrage when later revealing the “tablets” were actually chewing gum.

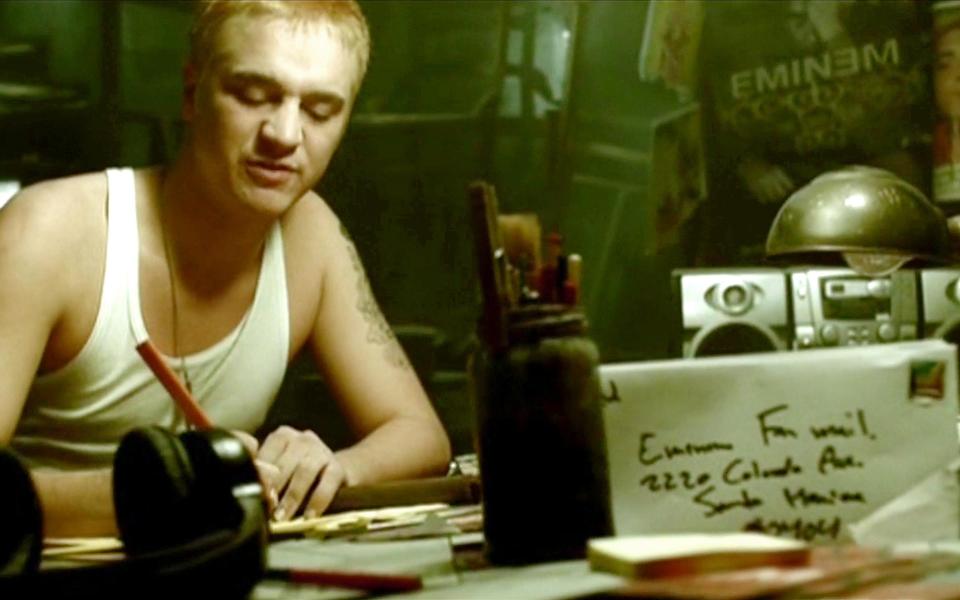

In the case of Stan itself, the contentiousness at the time had less to do with the song than the eight-minute video which took a literal approach in transposing the story to the screen. Many stations banned it outright. MTV, one of Eminem’s bigger supporters, cut all images of Stan’s wife tied in back of the car. And it removed one scene showing him guzzling vodka while driving.

The Stan video was directed by Dr Dre and Philip G Atwell, who had previously overseen the promo for My Name Is. Stan is portrayed by Devon Sawa of the Final Destination movies. The part of the bound and gagged girlfriend is played by Dido, who seemed surprised, but pleasantly so, to have been caught up in the Eminem whirlwind.

“I got this letter out of the blue one day," she recalled. “It said, ‘We like your album, we’ve used this track. Hope you don’t mind, and hope you like it.’ When they sent [‘Stan’] to me and I played it in my hotel room, I was like, ‘Wow! This track’s amazing.”

Ironically, where Stan had been exhaustively mapped out by Eminem, the tune that inspired it had come together relatively quickly.

“It’s one of those songs that took me only a few minutes to write,” Dido said of Thank You. “I was just sitting there thinking, I’m going to write a song about having a s--- day, and then one person, or anything – it doesn’t matter – makes it all okay.”

Life would imitate art. Eminem began to attract real-life stalkers. In 2007 a fan copied his number from Kim’s phone and then called up Eminem and asked that he listen to his demos. Mathers wasn’t impressed – even less so when his words were remixed into a song, Slim Sellout, posted to MySpace (his lawyers had it taken down). And just this year a second flesh and blood “Stan” broke into a Detroit property previously belonging to the rapper. According to TMZ, the man had been stalking him for months.

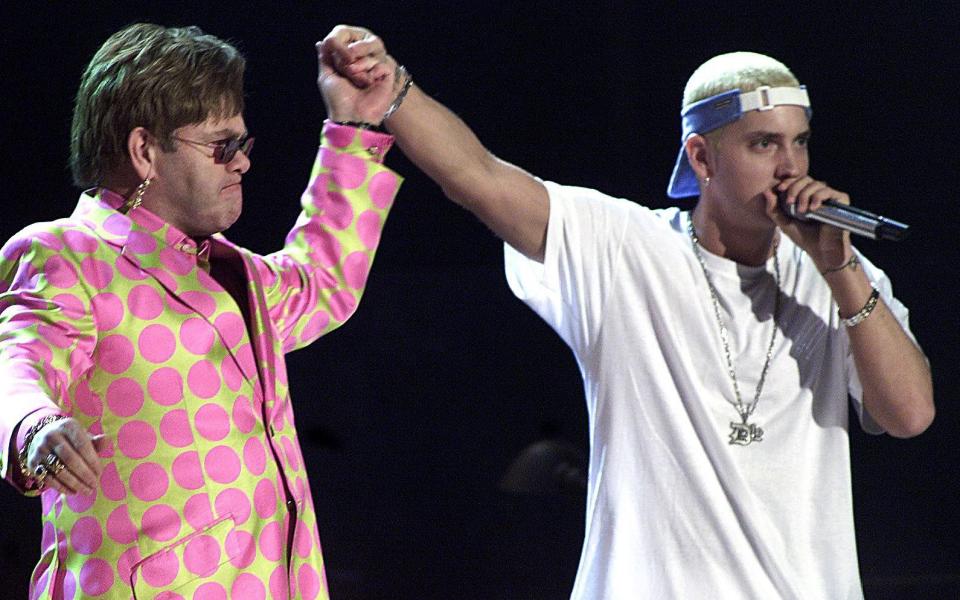

Not everyone joined the witch hunt against Eminem in 2000. In their generally approving reviews of the Marshall Mathers LP, critics singled out Stan for unflinchingly highlighting the dark side of fan culture. And Mathers found an unlikely defender in, of all people, Seventies piano crooner Elton John, who made a point of duetting Stan with Eminem at the 2001 Grammys, singing Dido’s lines.

“I don’t know why everyone is getting so crazy about this – it’s just pop music,” said Elton. “As a gay artist, I’m asked by a lot of people, “but what about the content of Eminem’s music?” It appeals to an English, black sense of humour. When I put the album on for the first time, I was in hysterics. If I thought for one minute that he was hateful, I wouldn’t do it.”

The criticisms would over time melt away (though they would surface again as Mathers taunted bisexual rapper Tyler, the Creator on 2018’s Kamikaze).

Stan, meanwhile, has carved itself into the culture – just ask Lana Del Rey. Fame, of course, has become considerably more complex in the 20 years since the Marshall Mathers LP. Now we stalk celebrities not just in the flesh but via Twitter and Instagram. Were he to pen Stan today, Eminem would have the narrator sending his idol direct messages on Twitter rather than trying to get in contact by letter. And yet its central message – that fame is weird, but hardcore fandom is weirder – endure.

“Everyone who lives and breathes someone else is probably taking it too far,” Eminem said in 2000. “And probably has something mentally wrong and needs to talk to someone about it.”