Sophie Marceau: ‘I know it was wrong... but I wanted the good parts’

“I’m not scared to bring dark, difficult subjects into the light,” says Sophie Marceau. Whether it’s the abuse of women in the film industry (which makes her “angry sometimes, angry often”) or assisted dying – the subject of her affecting new film, Everything Went Fine – Marceau believes we should “always be wondering and asking big questions out loud. It is in my nature to do this. I am not one to obey orders – c’est pas moi!”

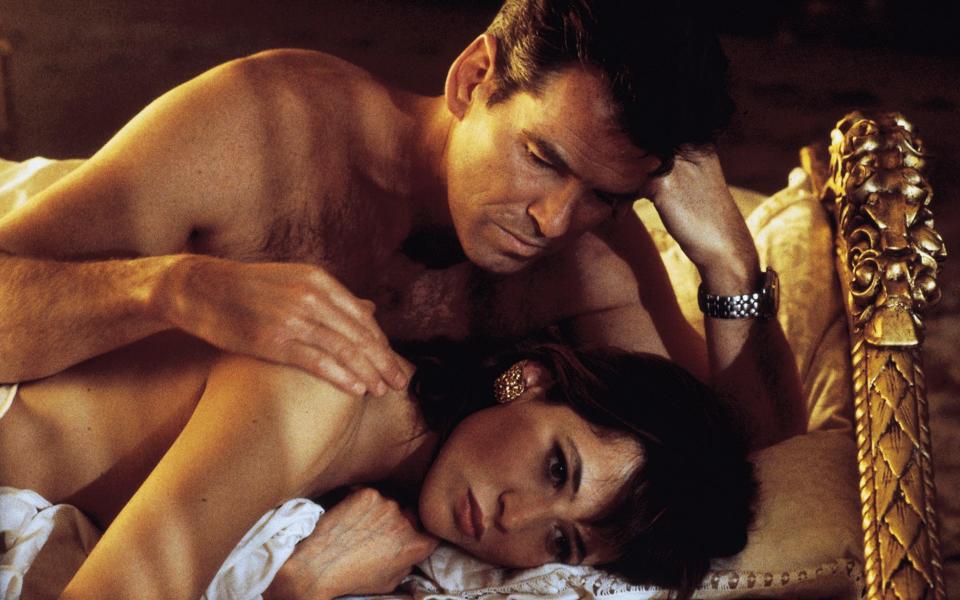

On the phone from her apartment in Paris, the 55-year-old French actress – who found international fame in the 1990s opposite Mel Gibson in Braveheart and as Bond villain Elektra King in The World Is Not Enough – sounds purposeful. She’s just back from Cannes, where she strode the red carpet in a spectacular scarlet cape and felt energised by the festival’s “ambience of youth and creativity”.

Marceau – who made her debut in 1980 aged just 13, as a fun-loving schoolgirl in La Boum (The Party) – has also been buoyed by the critical reception for her superbly understated performance in Everything Went Fine, in a role written specifically for her by French art house darling Fran?ois Ozon.

She plays Emmanuele, a writer whose 85-year-old father, André (André Dussollier), suffers a debilitating stroke – then asks her to help him die. In a series of flashbacks we are shown how the powerful businessman once bullied and belittled his young daughter so severely that she fantasised about killing him. But when he asks her to end his life, she finds things aren’t so easy – on either an emotional or practical level.

It’s a defiantly unglamorous film, featuring fountains of phlegm and hands shaking with Parkinson’s, and viewers might be surprised to find such a celebrated beauty as Marceau in it. Looking back through her old interviews, I’m struck by journalists’ tendency to objectify her, swooning over her “eyes that you might write poetry about” and “thick glossed hair that tempts the fingers”. One writer called Marceau “the most distractingly sexy woman I have ever met”.

“Better than a knock in the face, huh?” Marceau laughs, when I ask if such comments ever bothered her. “I’m not going to complain about being told I’m beautiful. It’s always pleasant to hear. But I’ve always been aware that beauty is temporary and I don’t want to get trapped by it.” She compares beauty to wealth. “You see those super-rich people, how horrible they feel when they lose a little money. All they can think is: I was rich-er! It’s ridiculous to be like that. If you can only focus on what you lose you do not see how much you have.”

She softens. “I’m getting older. I can never be more beautiful than I was and it would be sick to chase that. I need to be free in my work and that means feeling the emotions – not thinking about my wrinkles.”

Everything Went Fine is Marceau’s second film in as many months – though it could hardly be more different from I Love America, a frothy Amazon Prime rom-com in which she plays a divorced French film director looking for love in Los Angeles. “In French we don’t have this word ‘date’ – doesn’t exist,” her character. “Either we f--- or we don’t.” Today Marceau, who spent a few “very unhappy” years living in America early in her career before returning to France, tells me she relishes her Gallic identity whenever work takes her back to the US.

“We should not force ourselves to adapt to other cultures,” she says. “I feel so French in America. So French! I smoke. I don’t always wait for the green light to cross the road. I need to be seated to eat my meals. I speak out over there about religion, sex, politics… I love that. It makes salt in my life!”

Marceau sounds happy – but when I suggest that she has found contentment, she bridles. The daughter of a lorry driver and a shop assistant, she tells me she struggled with her early fame and blames it for her enduring loneliness. “When you get famous so young, you protect yourself by creating a bubble around your vulnerability,” she says. “The price you pay for safety is isolation. I see it now in the eyes of so many celebrities. The more famous they get the more lonely they become.”

She looks back with “sadness” on her teenage years, during which La Boum and its sequel, released two years later, made her a household name in France. Fame was such “a violent shock. I was overwhelmed. My family was overwhelmed. My face was on the cover of magazines but people were confusing me with the character I played. I don’t really know how I got through it. My parents kept my feet on earth, just enough, and they tried to make sure I was treated fairly but I remember the humiliation of some casting sessions.”

She recalls the distress she felt “as a 16-year-old girl, when those 50- to 60-year-old guys asked me: ‘Take off your shirt because it’s a sexy scene.’ They would order me as though I were nothing. You can’t use your age or authority to ask a young girl to undress. No way! I know it was wrong. But also, I was many times unsure what to do. I was an actress and I wanted the good parts. I understand why girls are taken advantage of.”

When pushed on the effect of the MeToo movement, Marceau says she’s aware that “the changes have been a little radical, a little violent. But it was necessary and I’m glad that women have louder voices and more authority now.”

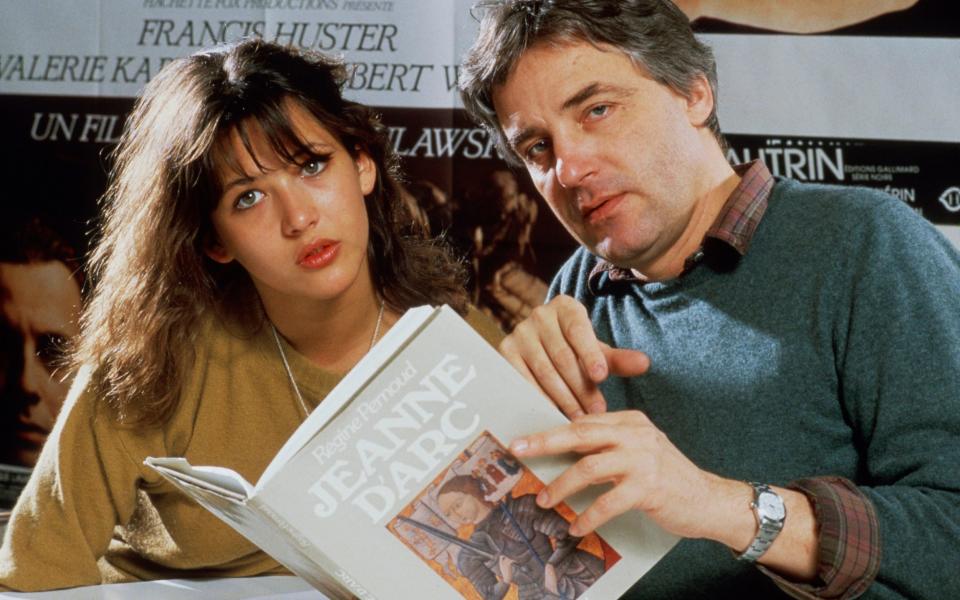

Marceau was still a teenager when she began a 16-year relationship with Andrzej Zulawski, a Polish film director 26 years her senior. (Their son, Vincent, was born in 1995.) I wonder if Marceau ever felt exploited by Zulawski, but she tells me she saw him as a “shield” who offered “protection” from the public scrutiny which she still feels left “some parts of me forever stuck at 13. I feel very old and very young at the same time. I’ve been working for 43 years, but I haven’t matured like other people.”

In 2001, Marceau left Zulawski for Jim Lemley, an American producer; their daughter, Juliette, was born the following year. She later spent seven years with the American actor Christopher Lambert.

Zulawski died of cancer in 2016, Marceau’s mother died in 2017 and her father in 2020. “Everything changes when someone close to you is between life and death,” she tells me. “You are turned upside down. I accompanied my parents to the hospital and I think that makes ideas of death easier. In France the [health] services are very good and the doctors and nurses came to care for them at home. And I was with them.” She takes a breath. “I think the most terrible thing that happened in the pandemic was that people died alone.”

Marceau says that the loss of her parents exacerbated the loneliness she first felt when she became famous – and it has intensified further since her children have left home, even though that’s “what you want, as a parent. You want them to fly on their own wings. It means you have done your job.”

Working on Everything Went Fine spurred her to talk to both her children about what she’d want them to do in the event of her death.

“It’s a disturbing subject,” she admits. “We all like to think we’re immortal. But it’s good to have a consciousness of those issues, or your death could be stolen from you. You need to discuss your wishes and your beliefs. You need to be honest about what you want for your body, your soul.”

Marceau stops short of telling me if she could ever imagine choosing to end her own life, like André in the film, but she will say that it seems “bizarre” to her “that people are shocked if you ask for that control. Isn’t it a good thing when a person knows exactly how and when he wants to die? You might agree or disagree but it’s not your life or your body. You have to respect their choice. It’s one less problem for the family.

“I haven’t figured it out yet, how I want to die,” she adds. “But I’m thinking about it…”

‘Everything Went Fine’ is in cinemas from Friday June 17