How the Smell of a Barnyard Is Roiling the Wine World

This story is from an installment of The Oeno Files, our weekly insider newsletter to the world of fine wine. Sign up here.

When is a wine flaw not a flaw? Some defects that can afflict wine, like TCA (aka cork taint), are always considered a fatal imperfection by experts across the board. But when we talk about Brettanomyces, it becomes much less clear. The aromas of bacon, BO, and barnyard in a wine have people retreating to camps, with one side welcoming these sometimes-pungent notes and others dismissing them right out of hand as defective. So we went out across the wine world to understand where people stood on Brettanomyces today and if we should consider it a fatal flaw.

More from Robb Report

Young Vintners Are Making Serious Wine. Now They Have to Convince Their Generation to Drink It.

How Acidity Affects Your Wine-and How Winemakers Try to Control It

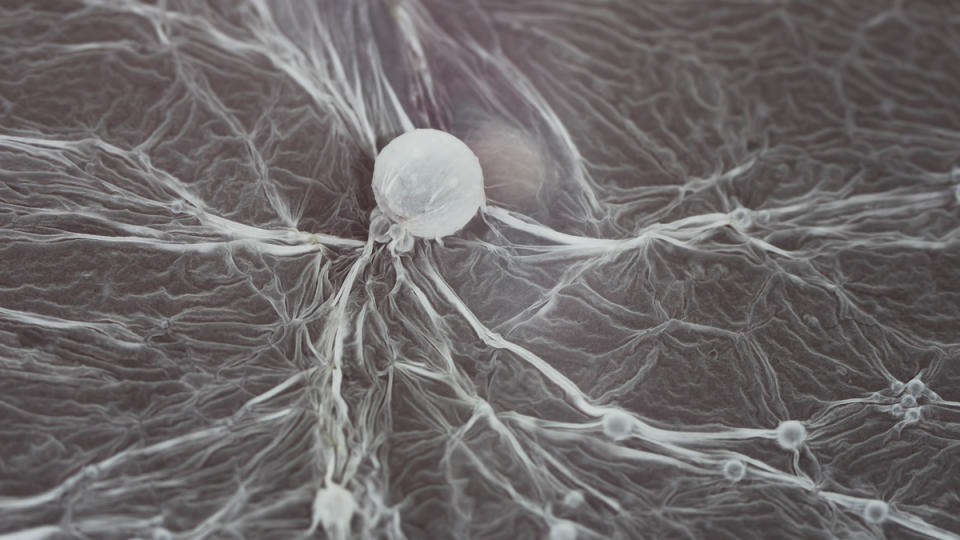

Referred to as “brett,” this strain of yeast thrives on grapes as well as barrels, walls, and in the air itself. And while you need yeast to trigger the fermentation necessary to make wine, not all of them are created equal. We don’t want to nerd out on the science too much here, but compared to the yeasts used in making wine, brett can throw off strong compounds that some love and others can’t stand. “If present in large amounts, it can overpower the wine and make it taste unpleasant,” says Heather Hyung Chang, a consumer and sensory scientist who is the CEO of Advintage Wine. She expects brett-y wine to have notes barnyard, spice, sweat, dirty socks, and smoke.

And yet, Chang doesn’t believe brett to necessarily be a flaw. “In small amounts, it can add a unique and interesting layer of complexity to the wine’s flavor profile, setting it apart from the rest,” she says. “While winemakers do not intentionally use brett in their wines, its presence in small amounts can create a pleasing final product.” In fact, descriptors like barnyard and dirty socks aren’t a dealbreaker to her at all. “The chemical composition of dirty socks and sweaty flavors is the same as that found in aged cheese,” she says. “Thus, some people might perceive these flavors as cheese-like in nature.”

Chang’s business partner Anthony Clark also thinks this yeast shouldn’t be avoided outright. “The brett-like characteristics found in red wines are already a part of their flavor profiles,” he says. “In fact, the subtle features that brett can induce in some aged wines are highly sought after by enthusiasts and connoisseurs.” Clark points to classics such as Bordeaux, Chateauneuf-du-Pape, Southern Rhone, Sangiovese, and old-school California Cabernet as being known for their “funk and soul, which offer positive qualities from brett.”

Mary Ewing-Mulligan, the president of the International Wine Center, believes brett shows its best self in Syrah from the Northern Rhone, some Grenache-based wines, and any red wines with earthy or stewed fruit tones. The flavors she attributes to brett—leather, barnyard, earthiness, and funkiness—are often ascribed to some of the finest wines in the world, especially from legacy regions. We would definitely add Rioja to that list; in fact, when we talk about traditional and modern styles of Rioja, the dividing line is often the presence or absence of brett.

Throughout our conversations we continually heard (and agree with) the idea that a little bit of brett is a good thing, but that when it is overpowering and makes wine taste bad, it becomes a negative quality.

However, not everyone concurs with this assessment, especially winemakers in Australia, who you may recall champion the screwcap over cork closures to reduce the incidence of TCA. Peter Gago, Penfolds’s chief winemaker, is clear in his convictions. “I think that any recognizable or detectable presence of brett in wine is a flaw,” he says. Gwyn Olsen, senior winemaker at Henschke Cellars (home of Hill of Grace) is on the same page. “Yes, Brettanomyces is always a flaw in wine,” she says. “While some amounts might add sweetness and complexity to one person, the amount could be detracting, hard, and metallic to another. Why a winemaker would work hard to make beautiful wines that speak of time and place and then intentionally allow a spoilage yeast to detract from this expression makes no sense to me.”

Liz Thach, president of the Wine Market Council, falls on the other side of the debate from these winemakers. She believes in moderation for brett, citing notes such as umami, mushroom, earthy, and forest floor—along with a mention of the barnyard—as the qualities she appreciates in a brett-y wine. For her, the wines from France and Italy can show the better side of brett, and she would recommend pairing them with red-sauce Italian dishes or seared steak with blue cheese, especially with an older Bordeaux.

When it comes to pairing brett-infused wine with food, we add grilled meat, stews, and any earthy dishes containing mushrooms, black olives, or Mediterranean herbs onto Thach’s suggestions. Chang and Clark recommend serving brett-style wines alongside dishes that have a “distinctive smokiness and funkiness,” such as charcuterie, which combines pungent cheese and a variety of meats that has been air-dried or smoked, each offering up their own complex, savory notes.

While we’re talking about food, we think it’s best to think of Brettanomyces like salt on a steak: a light sprinkle enhances the flavor and your dining experience, while a heavy-handed shake could render your prize cut of meat inedible. In other words: In the right hands, a little bit of brett can be a good thing.

Want more exclusive wine stories delivered to your inbox every Wednesday? Subscribe to our wine newsletter The Oeno Files today!

Best of Robb Report

Why a Heritage Turkey Is the Best Thanksgiving Bird—and How to Get One

The 10 Best Wines to Pair With Steak, From Cabernet to Malbec

Sign up for Robb Report's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.