Sex, stilts and Shakespeare: how Peter Brook's A Midsummer Night's Dream changed theatre for ever

Fifty years ago this week, something remarkable happened at the RSC in Stratford-upon-Avon. The penultimate production of the 1970 season was a staging of A Midsummer Night’s Dream so bold, lucid and revelatory that it blew the cobwebs off a cosily familiar comedy and marked a watershed moment for the company and for Shakespearean practice in the UK generally.

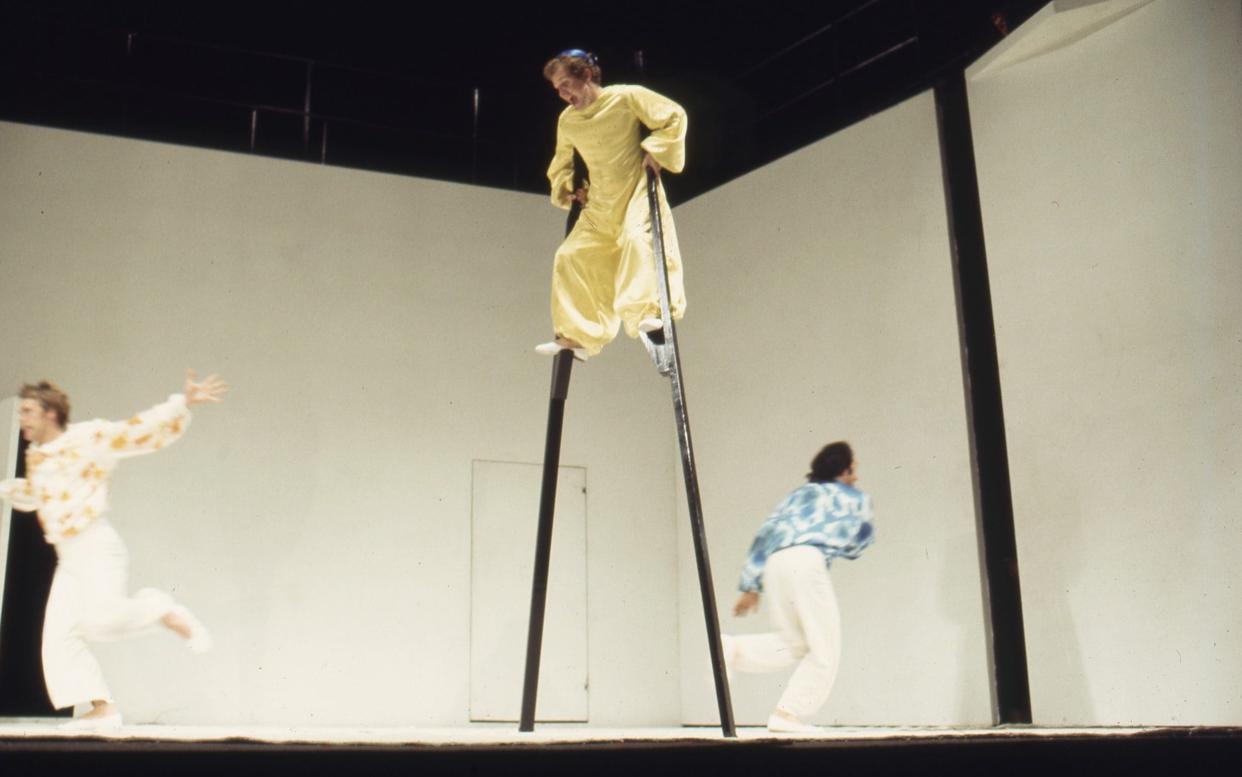

The opening night on August 27 was greeted with a standing ovation at the end, and at the interval too. “I’ve never seen anything like it before or since,” marvels the RSC’s then artistic director Trevor Nunn – “It felt revolutionary.” Instead of being confronted by leafy woodland scenery, the audience beheld three sides of a bright white cube from which all trace of the bucolic had been banished. The actors – with colourful satin robes for the principals – had become akin to lithe-limbed acrobats, dangling off trapezes, stilt-walking, plate-spinning. The fairies weren’t elfin and gauze-winged but were free-spirited, anarchic, and mainly male, one of them rudely thrusting a forearm between Bottom’s legs to suggest his perturbing transformation into a priapic donkey. The forest was suggested by dangling wires.

“That performance just soared and then overnight it seemed there was an incredible excitement about the production,” remembers Sara Kestelman, who played Titania. “Immediately it became this famous piece of work.” It went to New York, the West End, and then round the world, taking in Paris, Berlin, Venice. According to Sally Beauman, in an official history of the RSC published in 1982: “It became the most discussed, most written about, most analysed, and most imitated Shakespearean production of the century.”

The critics that evening foresaw and contributed to its towering status. “Once in a while, once in a very rare while,” began the New York Times review by Clive Barnes, “a theatrical production arrives that is going to be talked about as long as there is a theatre.” The sentiment was echoed by the Telegraph’s John Barber, declaring it “a production that will surely make theatre history”.

Director Peter Brook – the genius in question – was no stranger to acclaim. He had announced his prodigious talent at Stratford in 1946, aged 21, ravishing audiences with a picturesque Love’s Labour’s Lost. Soon moving away from the realm of the decorous, the industrious wunderkind made further waves with visually stark and commandingly acted accounts of the gorier side of the canon: Titus Andronicus (with Laurence Olivier), King Lear (with Paul Scofield).

All the same, his reboot of a customarily inoffensive school set-text was, even by his standards, a leap in the dark. Indeed, as Brook, now 95, recalls on the phone from Paris (his home and primary place of work since that production), it took a while for the idea of staging it to grab his imagination.

“The last thing I ever thought of doing was A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” he says. “There was a famous production by [Austrian director] Max Reinhardt that had real trees, live rabbits. I wanted nothing like that. I wanted to get as far away as possible from the idea of the fairy as a pretty young thing fresh out of school.

“Shakespeare in those days could still involve dozens of people on stage – I didn’t want that, or need a ballet choreographer. I said: ‘F--- that!’ ”. Abhorring then, as now, the directorial “concept” (“It’s a word that really makes me howl with despair”), his guiding principle was, he says, “Elimination. It was an act of spring cleaning – a sweeping out of all the dust and dirt, discovering what was there.”

The production came on the heels of the publication of his slim but influential theoretical tome The Empty Space (1968). “I had seen that an act of theatre only requires an actor in a space and someone watching them – and that above all the first thing was the space.”

It sounds like a simple recipe for artistic innovation, but Brook’s Dream resulted from a painstaking eight-week process. A source of inspiration was seeing the first visit to Europe of the Peking Circus, but he explains that he wasn’t wedded to the use of circus skills as an approach.

“It was trial and error. You never discover anything if you know what the result will be.” Given neither to self-congratulation (“Taking pride in something is alien to my nature – I don’t sit there thinking: ‘What a wonderful thing I’ve done!’ ”) nor to sentimental reminiscences (“The past is the past”) he does pay due tribute to the designer, the late Sally Jacobs. “I couldn’t think of the things we’d done together as hers or mine – we worked as a couple,” he says and rhapsodises too about the cast, which included a young Ben Kingsley and Frances de la Tour. They rose – “joyfully” – to the challenges thrown their way. “They found to their delight they could speak the verse while tossing a spinning plate to land on a stick with one hand while with another hand holding onto a cord and being lifted up.”

Kestelman still remembers the tingle-factor of mastering the art of plate-spinning/tossing: “Alan Howard [Oberon] and myself were both myopic, and for ages we would throw these plates to each other and miss. Then suddenly one of us caught one, and we kept catching them. And it was like a miracle.”

Not all was sweetness and light. Author David Selbourne was a fly-on-the-wall observer at rehearsals, recording the highs and lows in a book 12 years later. He noted such darker moments as Mary Rutherford (“Hermia”) wilting at an outburst from Brook, who scolded her delivery: “This is a descent into suburbia… A TV play of mumbled intimacy, a Stratford bus-stop meeting.”

“Brook was a guru figure, a lot of us were in awe of him,” Kestelman says, confirming that “there were times when he could be quite cruel”. But she offers a balancing view. “There was pushback from the actors and I think he welcomed that interaction.” The cast’s biggest victory was refusing nudity – “He wanted us to take our clothes off at the end and so have everything stripped. We said: No!”

Professor John Wyver, author, producer and scholar of the RSC’s performance history, saw Brook’s Dream as a schoolboy in 1971 and was bowled over by its “thrilling visceral beauty and power”. He identifies a striking contextual significance in the production’s emergence at the start of the Seventies. “I think it’s attuned to that moment. In a simplistic way, you can describe it as a hippy production. It has a sense of freedom, youth and challenge but it also has a sense of the darkness and complexity of the time.

“This was a production that didn’t hide the fact that at the centre of the story is a mature woman having sex with a donkey. The disturbing bestiality wasn’t hidden. Here was something that was pushing the sexuality of Shakespeare’s play up front in a way that very few productions up to that point had done.”

For Brook, the production belongs to its time, as all theatre does. He has rejected offers to revive it, and he turned away too from the idea of recording it for posterity (though a Japanese TV bootleg version exists, as does an RSC in-house audio recording and single-camera archival copy, the latter lodged with the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, while a few tantalising clips can be viewed on YouTube).

Brook’s Dream had a catalytic effect on Shakespeare performance. According to the late Jonathan Miller: “It liberated us all from literal representation.” Nunn argues that it helped make the RSC the world’s most famous theatre company, and immediately influenced a raft of directors – among them Michael Bogdanov, John Caird and Howard Davies. Brook emboldened radical approaches to rehearsal, and you can detect his legacy in the fleetness of foot of (Théatre de) Complicité and the “thinking outside the box” approach of younger directors such as Robert Icke and Rupert Goold. Such was Brook’s achievement that “No one wanted to touch A Midsummer Night’s Dream for years,” Nunn notes, although in the 1990s and 2000s Robert Lepage and Tim Supple memorably did do.

“When critics say ‘This is the Dream that lays Brook’s vision to rest’, that doesn’t seem to happen,” says Wyver. “There’s no other Shakespeare play – or play period – where one production has that centrality in the discourse. There’s no ‘defining’ production of Hamlet or Lear – they don’t occupy the same place Brook’s Dream does.”

For in-depth RSC discussions about Shakespeare visit rsc.org.uk

Further listening: Radio 4 The Reunion