The Secret History of Slim Aarons's Life as a U.S. Army War Photographer

Slim Aarons’s career-summarizing mantra is well known by now: For decades he photographed “attractive people who were doing attractive things in attractive places,” as he often said.

“I traveled all over the world to photograph them,” he once added. “I found them in London and New York, Gstaad and Newport, Palm Beach and St.-Tropez, and Lake Forest and Rome.”

His subjects included kings (past, current, and future), aristocrats, Hollywood’s megastars, indolent heirs, business icons and scions—many shot for Town & Country, to which he contributed for decades. Unique and revolutionary in its heyday, Aarons's body of work and aesthetic remains relentlessly influential today.

Aarons, who died on May 30, 2006, is better known for donning a cravat and linen jacket than military fatigues. However, he actually got his start as a combat photographer in World War II, covering some of the war’s deadliest battles, spanning North Africa, the Middle East, and Europe. He counted among his friends some of the most famous journalists of the war, including Robert Capa, Carl Mydans, and Ernie Pyle. And yet Aarons’s own wartime work and story are surprisingly little known.

Capa, Mydans, and Pyle were civilian journalists covering the war, but Aarons was an enlisted man—Staff Sergeant George Aarons, to be precise—and he photographed the war for the military magazine Yank. His pictures captured spy executions, bullet-and-bomb-pocked ruins, American GIs both in fierce battle and in repose, and traumatized orphans. Although he would later become renowned for documenting the realms of glamour and celebrity, his wartime experience paved the way for his later career in many ways.

“He saw the pain and ravages of war,” says his daughter Mary Aarons. “But he also saw Paris and Rome and London. The war gave him opportunities that weren’t otherwise available.”

The New York Times once characterized his wartime experience as a “stint as an Army photographer”—an assessment that likely displeased Aarons. For him, his six years in the armed forces were deeply formative. The war chapter “was a huge part of his life,” says Mary, who now wants to help make his wartime experience and works better known.

“It’s been one of my quests,” she says, “that more people learn about the full scope of his work.”

Much of Aarons’s postwar photography was mythmaking in its own right, creating visual fairy tales depicting aristocrats and film legends posing poolside or on manicured lawns, far removed from ruins decimated by artillery, torn bodies of soldiers, and the struggles of refugees. Yet Aarons may have been his own best mythmaking product.

For his entire life, George Allen “Slim” Aarons (b. 1916) claimed that he had been raised by grandparents in New Hampshire; his childhood as he described it resembled an E.B. White childhood full of farms and fresh air. For decades this WASPy narrative allowed him to operate freely among the bluebloods he documented.

Yet in 2016 a posthumous documentary, Slim Aarons: The High Life, revealed that Aarons had actually been born to a Yiddish-speaking immigrant Jewish family that lived on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. His family life was plagued with tragedy: an absentee father, a mother committed to a psychiatric hospital, a brother who killed himself.

For years the New England farm boy story fooled journalists, his friends, his colleagues, and his photographic subjects—even his wife and daughter, who learned the truth about his background along with the rest of the world. Aarons’s fabricated origin story seems part of a fraught tradition of American self-reinvention, as embodied in Jay Gatsby or Don Draper, fictional characters who erased humble or traumatic childhoods and came to embody high living.

“He created himself,” says photographer Jonathan Becker, who was a friend of Aarons’s. “It was all theater, but it was brilliant theater. It was the most amazing script, and most amazing life.”

It’s unclear when Aarons first came into contact with a camera, but it was likely in his teens, according to his friends and family. “He wanted to be a photographer,” Mary Aarons says. “We know that much.”

The camera proved to be his ticket out of poverty—along with the U.S. Army. With a second global war brewing, Slim joined the army on June 3, 1939, at the age of 23. Soon after enlisting, Aarons became a “technical staff sergeant,” and was made the official photographer of the United States Military Academy at West Point.

Even in those early days, against that military backdrop, Aarons charmed his colleagues and superiors. He was, as one fellow war correspondent recalled with affection, “an eminently self-confident string bean, six feet four inches tall.” Fairly irreverent about military life and decorum, Aarons often consorted with West Point’s top brass socially, as he would mingle with his elite photography subjects after the war. “At the Point, Slim got to know, on a first name basis, the colonels who became the multistar generals of World War II,” recalled Barrett McGurn, who, like Aarons, would cover the war for the army.

“I was a big hero there,” Aarons told Vanity Fair in 2003. And, he added, he “became very looked after by the sergeants’ daughters.”

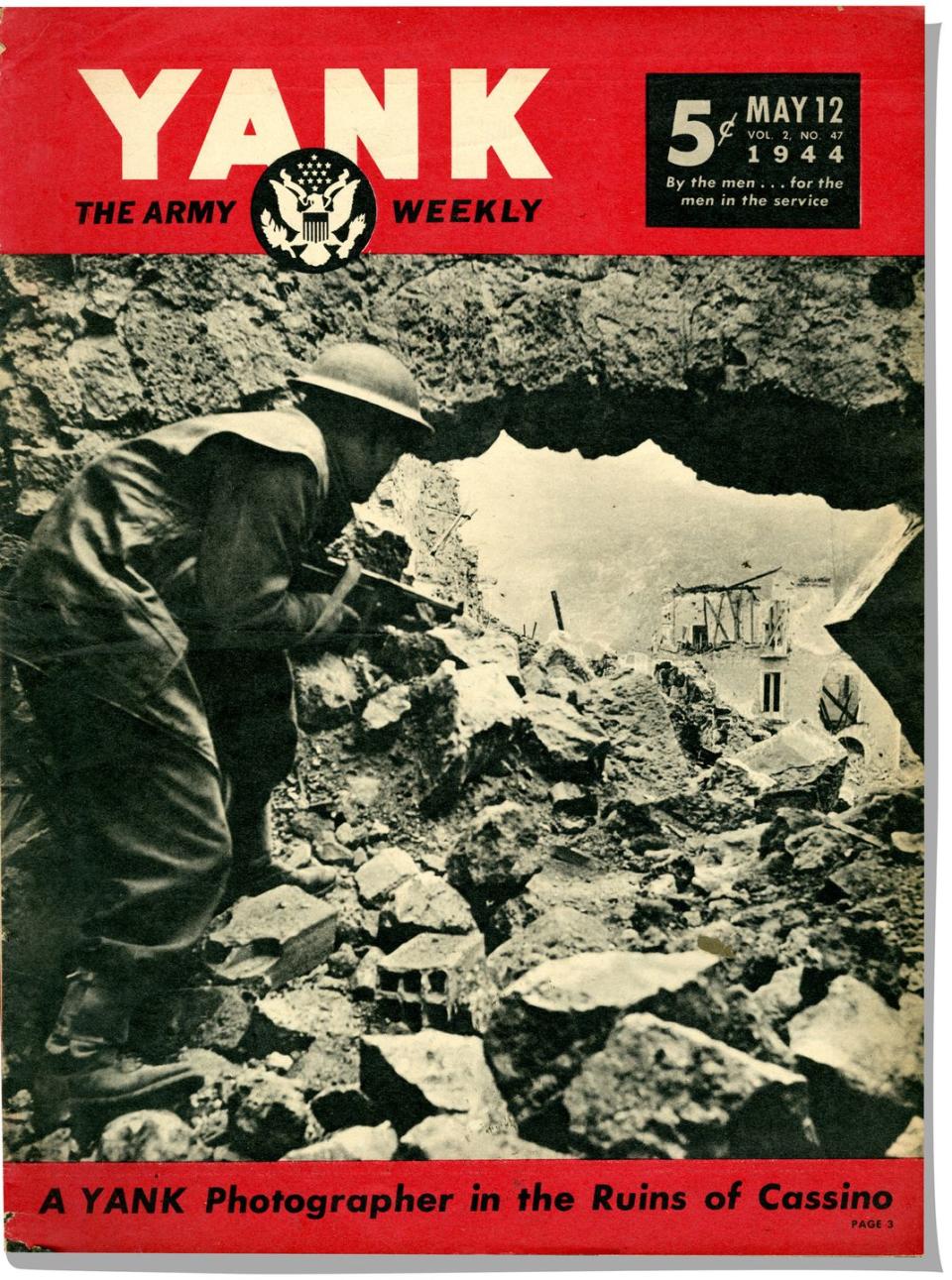

In 1942, while still at West Point, Aarons met Hollywood director Frank Capra, who had received a commission as a U.S. Army major and was working on movies for the military. Capra was also recruiting talent for a new weekly military magazine called Yank, an offshoot of the publication Stars and Stripes. Like Stars and Stripes, Yank would “be entirely for and by the soldiers.” Aarons eagerly volunteered and was soon dispatched to London to begin his new assignment. “Capra got me out,” he later said, adding that his new magazine placement was “quite a thing for a kid like me.”

For other enlisted men, heading to war-torn Europe might have seemed like a death sentence, but for Aarons, here was another career opportunity—provided, of course, that he survived. Yank became one of the world’s first truly global publications, with 21 editions in 17 countries and a circulation of 2.25 million. For Aarons, shooting for Yank offered not only trial-by-fire training as a photographer but a way to make a name for himself.

Combat photography was relatively new then; World War II has been called the first media war. For Aarons and his war correspondent colleagues, the job of documenting the deadliest conflict in human history would be daunting and often terrifying—but it was undeniably righteous. Allied photographers were charged with preserving a graphic historical record of the war, and in doing so were also providing an example of democracy in action. Some of the army’s top generals adopted the cause of press freedom as they fought the Nazis.

“A soldier’s newspaper…is a symbol of the thing we are fighting to preserve and spread in this free world,” wrote General George C. Marshall in Stars and Stripes. “It represents the free thought and free expressions of a free people.”

Whereas civilian reporters were bound by the Geneva Conventions to act as non-combatants, Aarons and the other new Yank correspondents went fully armed into combat and were expected to pull their weight in military operations. In addition to mess kits, typewriters, and cameras, their field equipment often also included carbine rifles, .45 pistols, and even hand grenades. Yank journalists were instructed to get as close to front line action as possible, and make sure to live “long enough to record it.”

“[We were told], ‘Now fellas, when you are lying in that foxhole and all the firing is going on, I want you to remember: Get that story!’” Aarons later recalled. Even if he was lying on the ground, wounded and bleeding, he was instructed to remember one thing: “Send back the story.”

In London, Aarons’s height immediately set him apart, along with the affable charisma that had earned him favor at West Point. Several years earlier, he had been desperate to escape his troubled childhood; now he was drinking in England with famed Life photographer Robert Capa and taking pictures of Winston Churchill at Downing Street. (Never mind that Churchill had reportedly been drunk during the session, and that the photos were ruined in a development lab.)

“He was so charming and boyish and was always such an Archie character, that everyone took him under their wing,” says David Friend, former photo editor at Life, current Vanity Fair editor, and a friend of Aarons’s. “He just seemed to be this charmed character whom fate would look kindly upon.”

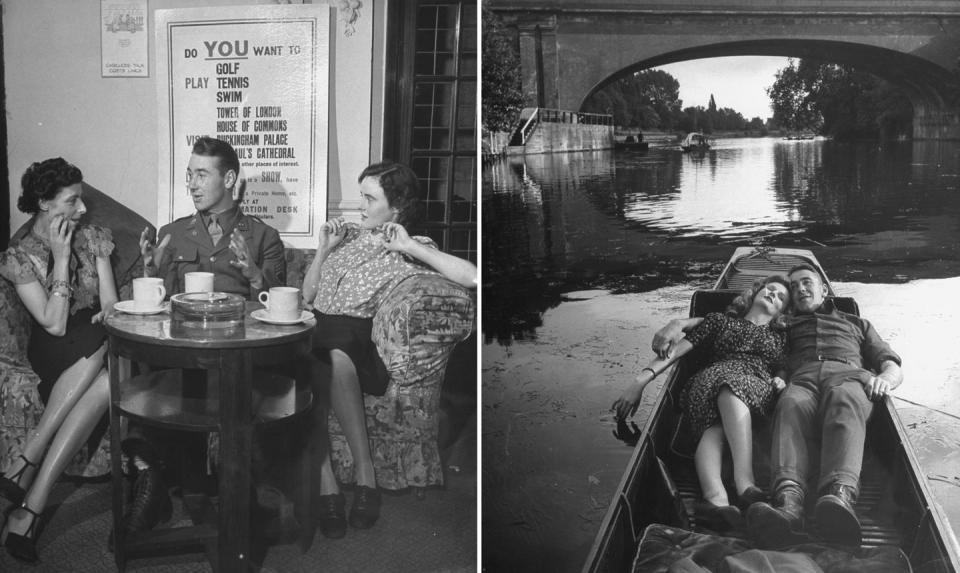

Shortly after his arrival in England, his new friends at Life spotlighted Aarons in an amusing spoof feature. The U.S. War Department had issued to U.K.-based American soldiers a pamphlet titled “A Short Guide to Great Britain,” which aimed to familiarize enlisted men with British etiquette and customs. The Life spoof, “How to Behave in England,” depicted Aarons making one American blunder after another. In one photo he is shown canoodling with a British soldier’s girlfriend in a punt; another image depicts him cluelessly butting in on locals at a pub.

“Here [is] Slim as gauche as anybody could be,” reads one caption.

The fun quickly ended when Aarons was dispatched to Cairo, one of the first Yank journalists to enter a theater of war. His equipment: an army-issued, burdensome Speed Graphic camera, which he hastily swapped for a small Leica. His assignment: to cover the British counterattack on German forces in North Africa. Along with Yank writer Sgt. Burgess Scott, Aarons traveled with the British Eighth Army under Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, from El Alamein to Tunis. The team was often under fire.

“There was an incredible bombardment,” Aarons later recalled. “We [were] living in foxholes.” Some correspondents thrive during combat coverage, but Aarons was terrified. “War in the desert is not like war anywhere else in the world,” he added. “You can see nothing. [The Germans were] using ambulances to bring weapons, and so were we. In war there are no rules. I was getting bombed. I was a kid in the slit trenches, and the Germans were coming over at night. It was not like today, where you have radar and all that. We had nothing.”

There were a few small, unlikely rewards as they traveled across the desert with the troops. Upon entering the devastated city of Tobruk after it fell into British control, Aarons and another reporter found a stash of Mussolini’s Italian mineral water intact in a damaged building. They bathed in it.

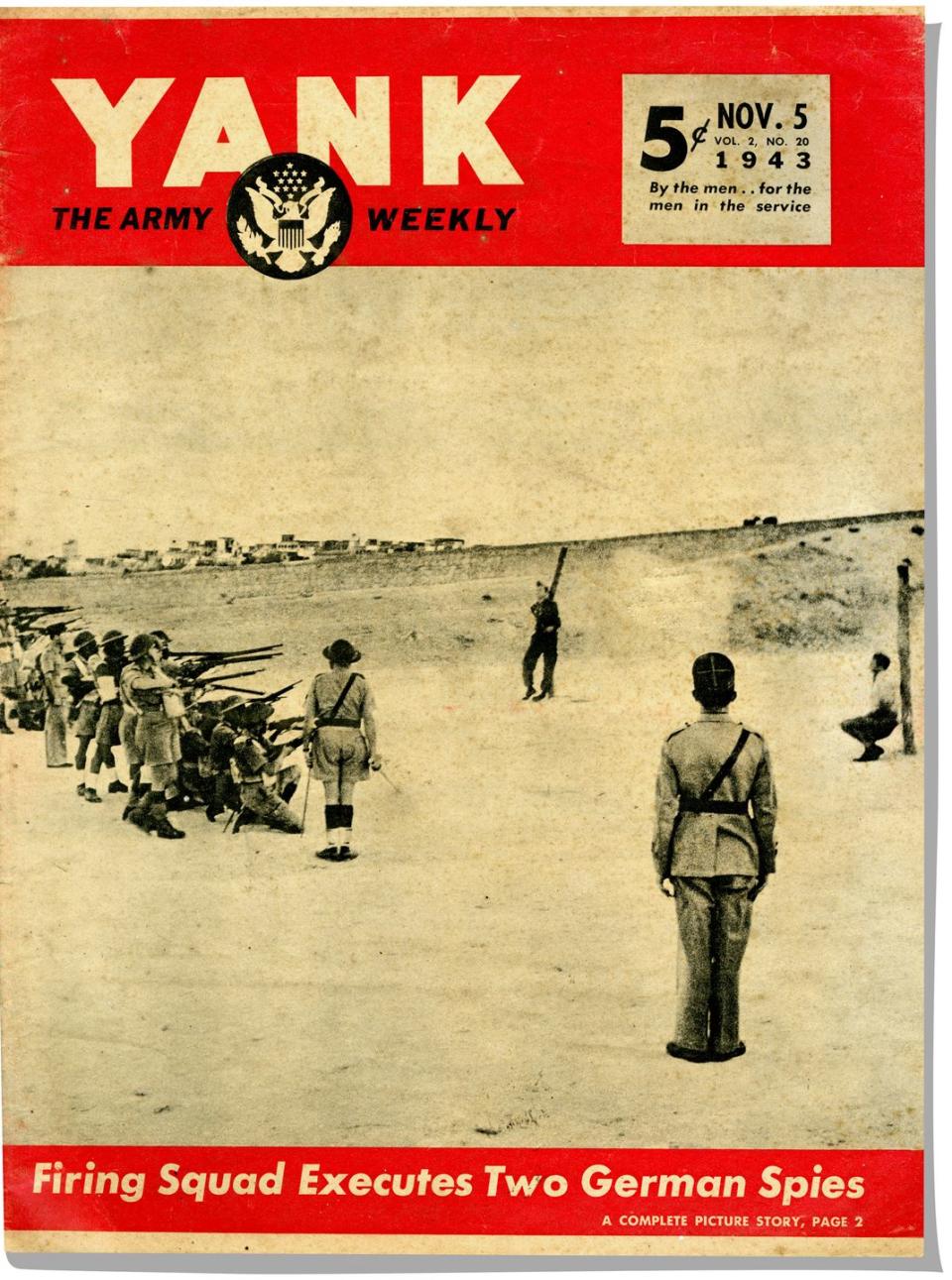

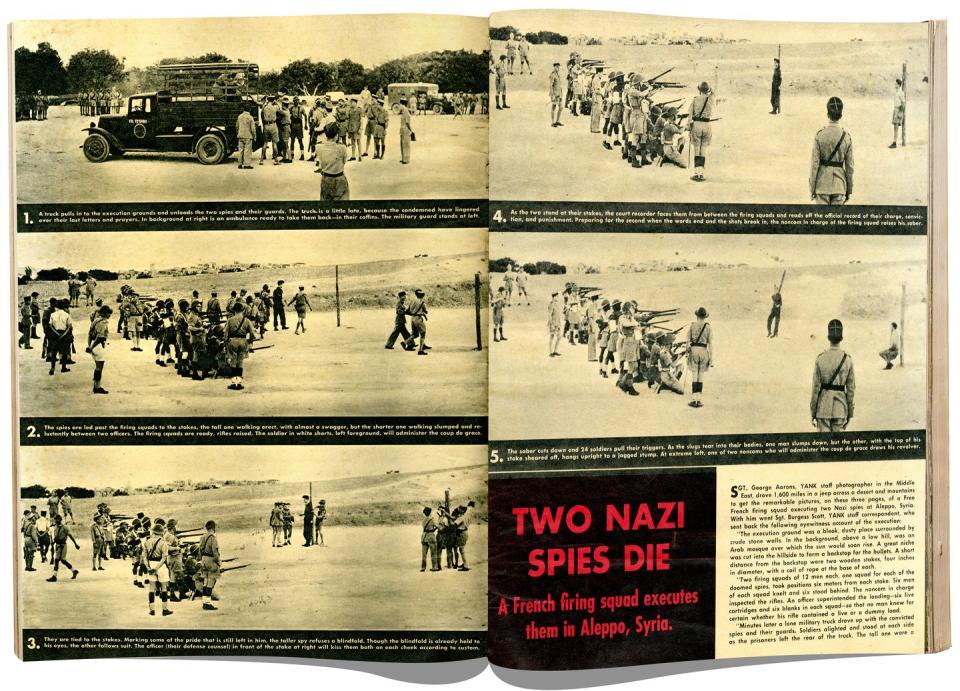

There is evidence that Aarons did occasionally relish the adrenaline—and getting scoops. When he and Scott heard that Free French forces were preparing to execute several Nazi spies in Syria, they got into a jeep and drove across 1,500 miles of desert and mountain terrain to Aleppo, arriving in time to witness and document the firing squad in action. Aarons sent the film to his Yank editors with a penciled note on the envelope that said, “Hiya, Joe and Leo. How do you like this for a story?”

The editors liked it just fine. One of the Aarons photographs captured the moment that the firing squad had aimed at one of its prisoners. The moment-of-death image spread across two full pages of the magazine.

Because Aarons was Aarons, he got away with things few other enlisted men could. Other GIs wore uniforms. Aarons, on the other hand, “dressed as he pleased,” according to Barrett McGurn, former Yank war correspondent and historian of the magazine.

“Everything was loose,” Aarons later recalled. “I went where I wanted. I did my job.”

For Aarons, wearing civvies instead of military uniform was not just a matter of personal preference; doing so gave him the sort of entrée denied to most enlisted men.

“Changed dress, he found, opened the way into ‘officer country,’ where liquor flowed and life was easier,” McGurn recalled.

Aarons clearly grasped that, even in combat zones, sartorial presentation affected impressions and created access. He would later use this lesson to move among the upper classes he documented in postwar life, when he was, as David Friend put it, perpetually “ascot prone.”

When Aarons left Africa to cover the war in Italy, he was also somehow able to get his precious jeep—now in his permanent command, giving him more freedom than other correspondents had—loaded onto a transport plane. The vehicle would allow him to traverse the country and eventually much of Europe.

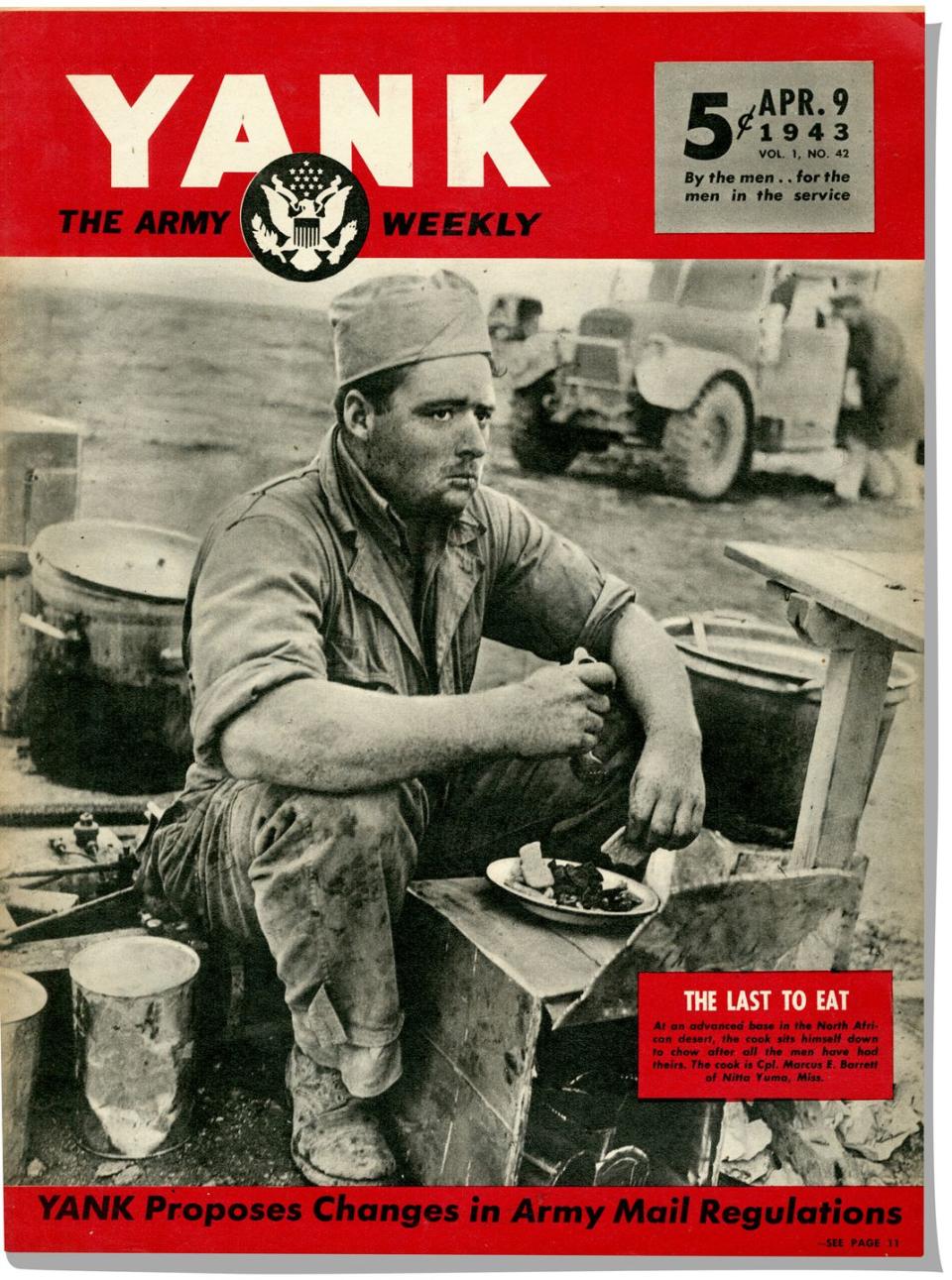

Not everyone succumbed to Aarons’s charm, however. In its April 9, 1943, issue, Yank ran his photo of an exhausted and unkempt U.S. Army cook based in North Africa. The image of the disheveled GI caught the attention of General George S. Patton, who immediately “went berserk,” according to McGurn, and cabled the War Department, alleging that Yank and Aarons were “encouraging dirt and disorder among the troops” and demanding strict censorship of the magazine.

Patton’s ire was not something to take lightly. Nicknamed “blood and guts,” the general was feared and reviled by many GIs and war correspondents. Time journalist John Hersey considered Patton an unhinged megalomaniac who had “lost his marbles in Sicily” and had become a “cruel and despotic officer…just the thing we were fighting our war against.” Andy Rooney, then at Stars and Stripes, called him “a loudmouthed boor who got too many American soldiers killed for the sake of enhancing his own reputation as a swashbuckling leader in the Napoleonic style.”

Yank’s editors decided that only another general would be powerful enough to fend off Patton’s rage and defend Aarons. They found a defender in General Marshall, who duly provided the necessary shield. The magazine should remain uncensored, he asserted, and Aarons avoided official reprimand. (“Don’t pay any attention to that crazy George Patton,” Marshall wrote. “Tell those boys on Yank to keep putting out the magazine just the way they’ve been doing it.”)

It was ironic, though, that Aarons, later famous for documenting some of the world’s best-dressed people, had caused an incident that pitted two of the U.S. military’s top commanders against each other—over a photograph of one of the Army’s worst-dressed servicemen.

After the war Aarons would set up a Rome bureau for Life and document the post-conflict dolce vita in that city and beyond. But in 1944 he was nearly killed in Italy. That year Allied forces began an invasion at the Italian beach resorts of Anzio and Nettuno. The attack was supposed to be enough of a surprise that it would create an easy toehold for Allied forces to make a push for fascist-controlled Rome, but it took 10 days just to secure the beachhead, and the battle that ensued turned into a protracted operation with heavy casualties.

Aarons and his accompanying Yank writer Sgt. Burgess Scott were appalled by the scenes they witnessed when they accompanied the forces invading Anzio. The little Yank team made it onto the beach and found that the reality of the deadlocked invasion was worse than they had anticipated. Pinned down on the coast by German forces, Allied troops had honeycombed the beaches with thousands of foxholes, in which GIs sometimes drowned during bad weather high tides.

“On the beachhead every inch of our territory was under German artillery fire,” reported Scripps-Howard newspapers correspondent Ernie Pyle, who covered Anzio at the same time as Aarons and Scott. The town had been devastated and emptied of civilians. “Everywhere there was rubble and mud and broken wire,” Pyle said.

Aarons and Scott—along with Pyle, Capa, and around eight other correspondents—moved into the basement of a waterfront villa that was miraculously intact. Enemy long-range artillery had been firing on the immediate area for weeks, “yet the villa had seemed to be charmed,” Pyle said.

The run of luck was bound to end, and all the reporters at the villa seemed to sense it. Pyle later recalled that he and Aarons had been talking one night about how close the latest German barrages were to their position, and the very next morning the house came under fire. One explosion threw Pyle across the room and pelted him with shards of glass.

“One gigantic explosion came after another,” he recalled. “I sat cowering in the corner.”

Neither he nor Aarons was seriously hurt in the attack, but Aarons did receive a Purple Heart for a forehead wound. (The injury had no long-lasting repercussions, says his daughter Mary. Nor did Aarons hold the Purple Heart sacred; he later claimed that he gave it to a pretty blonde.) That said, Aarons had been correct when he later recalled that he had “nearly been blown up in Anzio.” German aircraft had dropped numerous 500-pound bombs in the area, some of which hit within 30 feet of the villa.

Aarons toyed with the idea of telling his superiors that his equipment had been wrecked in the attack, but he stopped out of fear that Yank’s accountant “might go out and shoot himself.” Yet somehow not a roll of film or his camera was damaged. Pyle mentioned Aarons and the attack in a subsequent column, bringing the sergeant immediate fame back in the United States.

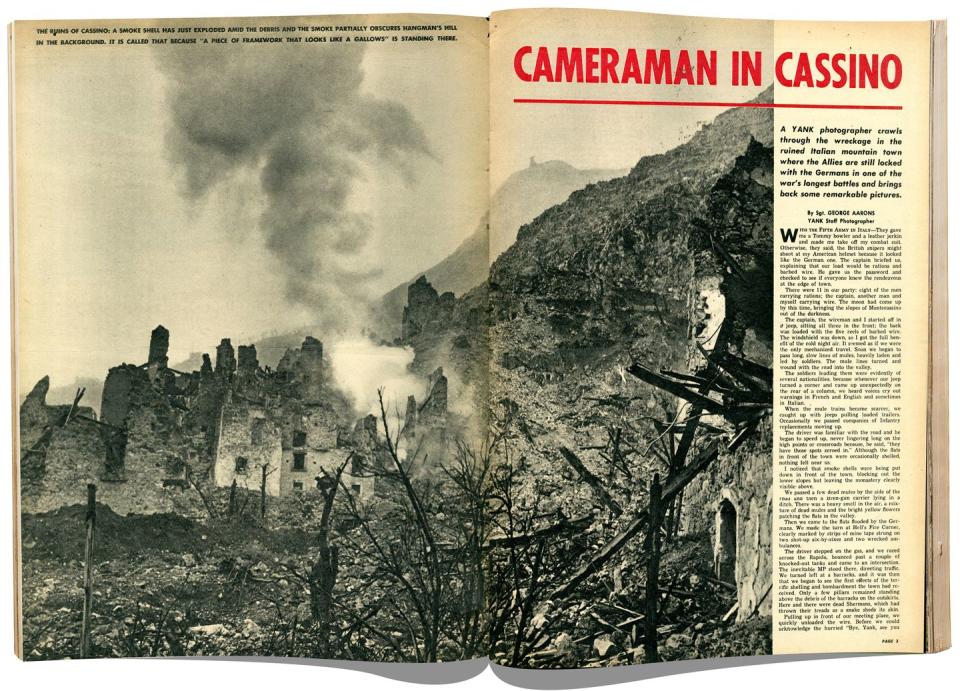

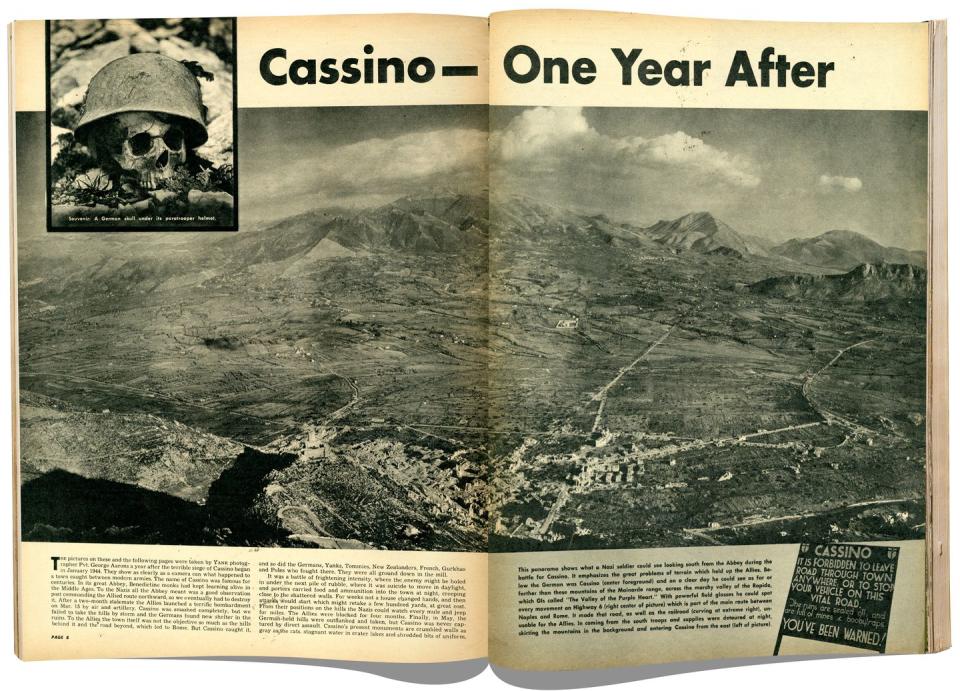

There were other close scrapes with death in Italy. Aarons made several visits to the front at Monte Cassino, including one mission in which he assisted a unit bringing rations and barbed wire to the front. The valley they would be crossing had been grimly nicknamed “the valley of the Purple Heart.”

“The big guns were splashing the sky with angry dabs of flame,” Aarons recalled in a Yank article about the mission. The town was in flames; mortar shells exploded all around his company; the sound of machine guns was constant.

Suddenly, a shell fell within a few yards of Aarons and his company: “There was another crash and a burst of flames, and the ground shook under us.” He later admitted to another reporter that “I was so scared I shit in my pants.”

The company eventually made it to a safe house—or, rather, a thick-walled home that had thus far withstood the relentless shelling. Aarons thought about trying to photograph the scene but was too afraid to leave the building.

“You can’t even think about going outside,” he later recalled. “The Germans are screaming, there are star shells, you think, ‘Jesus, what am I doing here?’ You can’t do a goddamn thing.”

“War is not,” he added dryly, “like it is in the movies.”

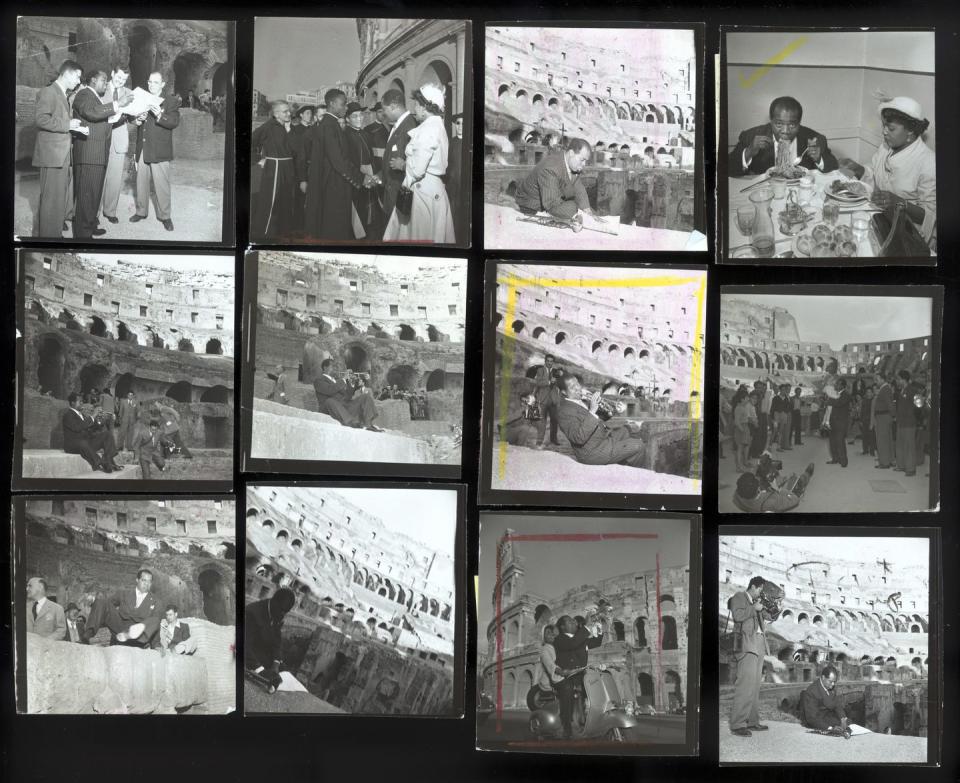

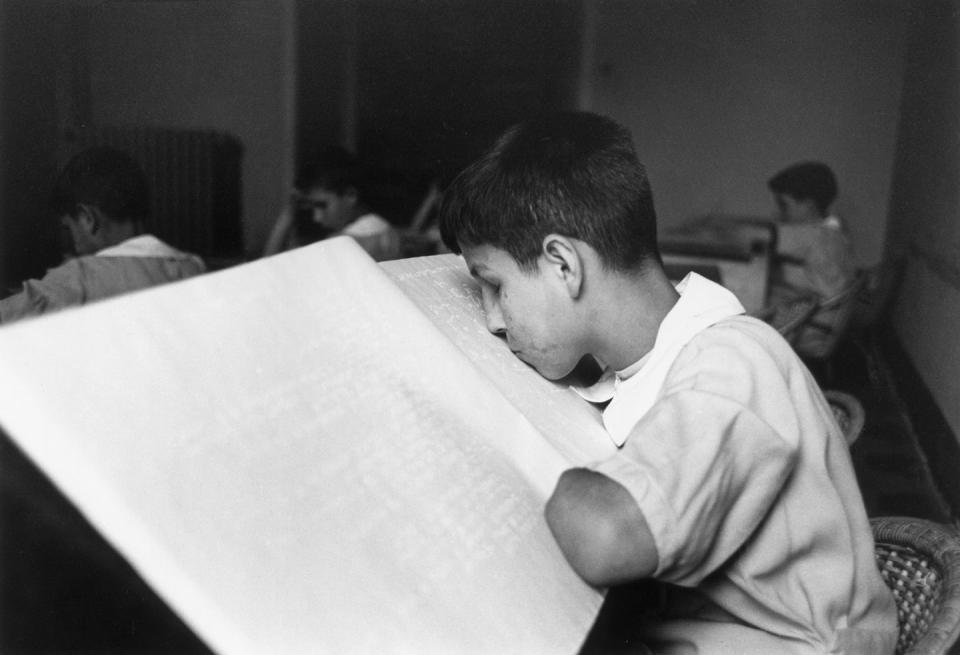

As the Allied forces battled their way across Europe, Aarons drove his jeep into one liberated city after another. In the summer of 1944 he accompanied advance tanks of the U.S. First Armored Division into Rome, reportedly “liberating” a brewery with some of his fellow war correspondents along the way. In the aftermath of Rome’s liberation, Aarons took some of his saddest wartime photos—young orphans taking refuge in a convent, a blind amputee trying to teach himself to read Braille with his tongue—but he also managed to stage a fairly fashionable shoot in the city, using a lovely 16-year-old red-headed Italian girl named Jean Govoni as his subject.

“Mr. Aarons took me to Mussolini’s balcony in Piazza Venezia,” Govoni later recalled. “He had me pose on it, tossing biscuits to the crowds. Mussolini’s balcony!”

The joyous image arguably foreshadowed the work he would do in that city after the war.

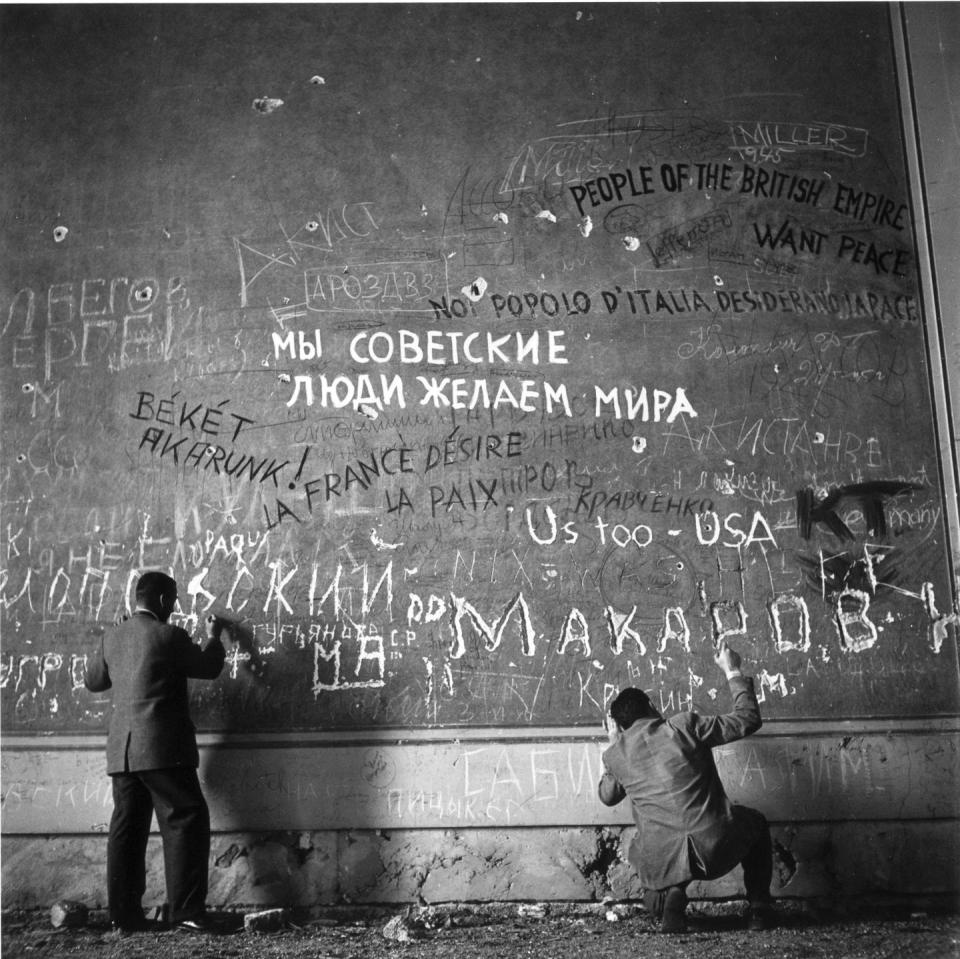

After Paris was liberated in August 1944, Aarons celebrated in that city with Robert Capa, author William Saroyan, Time and Life correspondent (and future wife of Ernest Hemingway) Mary Welsh, and other reporters. Yet Aarons would not be satisfied, he told his editors, until he drove his jeep right up to the front door of Yank’s Berlin bureau. In 1945 he got his wish. Once he got to devastated, post-surrender Berlin, Aarons took a photograph of Hitler’s chancellery, not long after the dictator’s suicide. The walls were covered with graffiti left by triumphant British, French, Russian, and American soldiers.

After the Allied victory in Europe in June, Aarons did not, like some other war correspondents, head off to cover the war still raging in the Pacific. Pyle, who had emerged relatively unscathed from the Anzio bombing, had been killed by a Japanese machine gun bullet on the island of Ie Shima in April. The Japanese surrendered on August 15, 1945. Aarons would soon return to the United States and walk in a victory parade down Fifth Avenue, in his native New York City. He had survived the deadliest conflict in human history. Some 45 million civilians and 15 million combatants around the world had not.

Many of his colleagues went on to cover new wars in other parts of the world. Aarons, on the other hand, immediately said goodbye to all that, and quickly moved on from devastated Europe to Hollywood, where he began to photograph the stars and starlets of the day. When given the opportunity to cover the war in Korea several years later, Aarons informed the inquiring editor that he was not interested in partaking in another invasion from the sea—and that the only beaches that interested him had beautiful girls sunbathing on them.

Aarons’s whiplash switch from documenting death and decay to photographing the sparkling artifice of high society and celebrity may strike some as startling. But to others the transition seems “very, very logical,” as Jonathan Becker puts it.

“He’d been wounded and seen horrors and deprivations and blood,” Becker says. “The intensity of the war experience—the adrenaline, the life and death of it—can’t help but give one a greater appreciation of taste and one’s senses…and intensify one’s appreciation of finer things.”

“I was eager to put all that misery behind me,” Aarons later recalled. “Having survived, a little battered but all in one piece, I felt I owed myself some easy, luxurious living to make up for the years I had spent sleeping on the ground in the mud, being shot at and bombed.”

“I had had my fill,” he added, “of photographing human suffering and despair.”

You Might Also Like