The Secret History of Journalism's Biggest Scoop

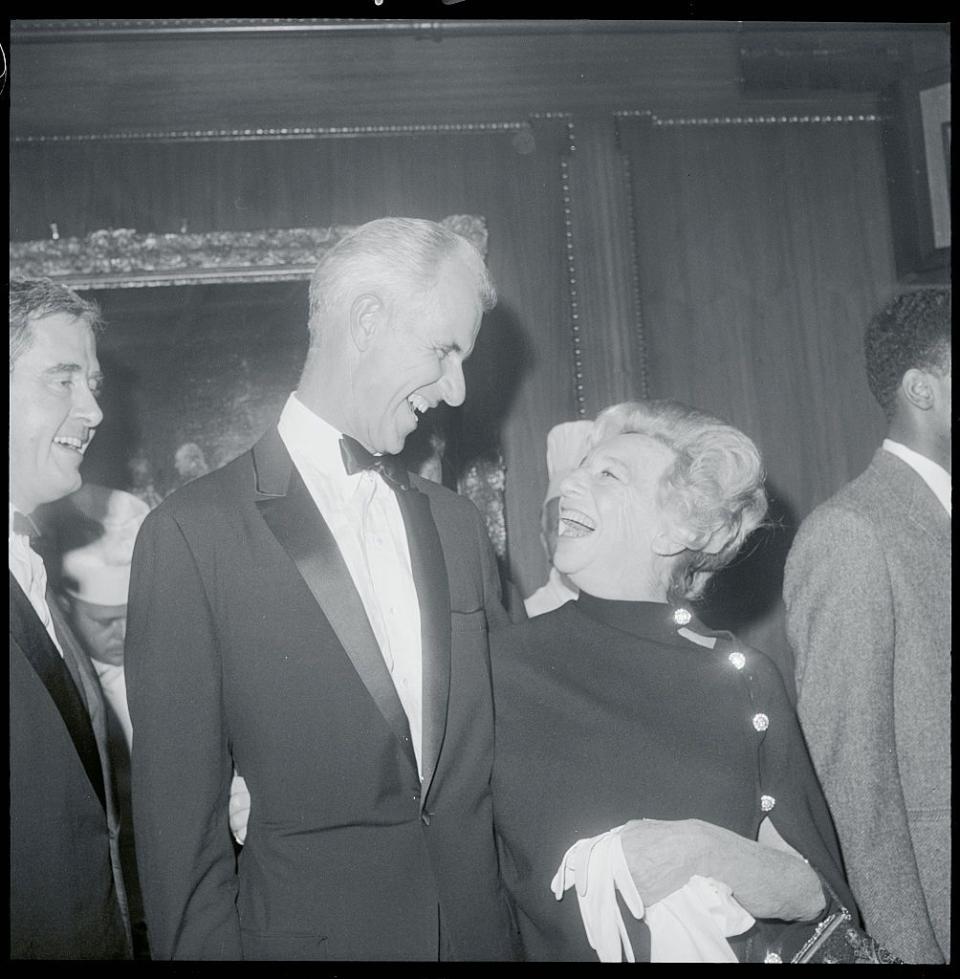

In late fall 1945, war correspondent John Hersey and the New Yorker magazine’s deputy editor, William Shawn, had lunch. It likely wasn’t a glamorous affair; “[Shawn’s] idea of a power lunch was orange juice and cereal in the Rose Room at the Algonquin Hotel,” long the regular gathering place for some of the New Yorker’s most vicious and brilliant contributors.

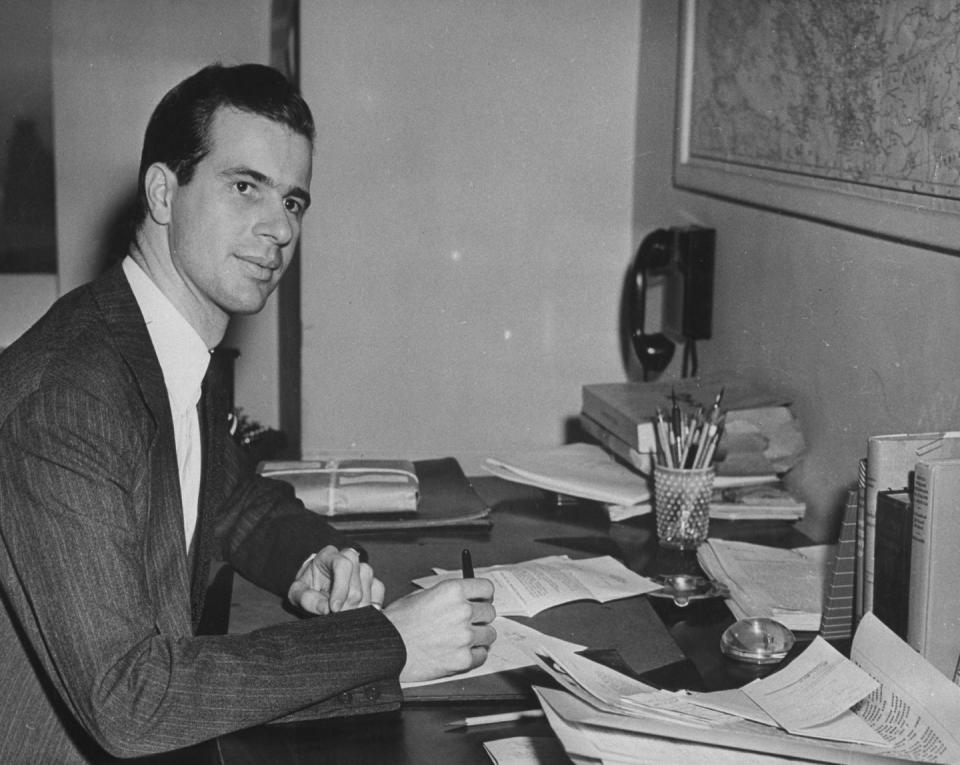

Hersey had written a couple of military-friendly pieces for Shawn and his boss Harold Ross, co-founder and editor of the New Yorker, including a profile on a young naval lieutenant named John F. Kennedy and his recent ordeal in the Solomon Islands, in which a Japanese destroyer had charged his PT boat and cut it in half, killing of his men. Only thirty-one years old, Hersey was a respected international reporter, a Pulitzer Prize–winning author, and a commended war hero. Now that the war was over, he had decided it was time for him to begin overseas reporting again and was planning a major, months-long trip to Asia.

At lunch, as Hersey and Shawn went through possible story ideas, they discussed Hiroshima. The New York Times, the only news outlet to have an eyewitness reporter on the Nagasaki bombing run, would boast to advertisers that it had scooped the world on the story of the atomic bomb and the dawn of the atomic age; it remained, as one New Yorker writer put, “the biggest news story in the history of the world.” But for Hersey and Shawn, something essential was missing from the reporting that had initially surrounded the August 6 and August 9 atomic bombings of Japan. They identified what had seemed so disturbing and incomplete about the coverage so far.

“Most of the reporting up to that time had to do with the power of the bomb and how much damage it had done in the city,” Hersey later recalled. While it seemed like the coverage had been comprehensive, most of the information had actually dealt with landscape and building destruction. Months had now passed since the nuclear bombing of Hiroshima, and still very little had been published on how the atomic bomb had affected its human victims.

A few early-arriving Allied reporters had managed to get out some distressing dispatches about the fate of Hiroshima, and there were dozens seasoned, ambitious foreign correspondents now based in Tokyo. Yet no one had yet followed up with a major, comprehensive story on the true fallout there, and what Hiroshima had looked like under the “impenetrable cloud of dust and smoke [that once] masked the target area,” as the New York Times put it.

Furthermore, what initial coverage there had been was now tapering off. Other stories had since edged out front-page Hiroshima and Nagasaki headlines. When Americans opened their newspapers each morning, they instead saw news of the homecomings of American troops, the reconstruction of Europe, the Nuremberg trials of war criminals in Germany, and, of course, the escalating antagonism between the United States and the Soviet Union, among other international developments.

It is unclear whether Hersey and Shawn knew the extent of the restrictions that had been imposed on Tokyo-based reporters, but they likely had some idea. The American journalism world was very close-knit then, and many of Hersey’s correspondent friends had been posted to Japan to cover the occupation. In any case, it was clear that the U.S. government had been put on the defensive after the initial Hiroshima press reports came out, during the chaotic first days of the occupation. Both in Washington, D.C., and in General MacArthur’s Tokyo, U.S. officials had immediately gone into overdrive to contain and spin the story of the A-bomb aftermath.

In September, a report had appeared in London’s Daily Express, alarmingly titled “Atomic Plague,” and described a mysterious and horrible disease ravaging Hiroshima’s blast survivors. (A similar report about a dreadful “Disease X” plaguing Nagasaki’s survivors, filed by Chicago Daily News reporter George Weller, was intercepted and “lost” before it could go into publication.) Shortly after Burchett’s Daily Express report sent ripples of horror around the world, editors of major American publications—Ross and Shawn likely among them—had received a confidential September 14 letter from the War Department, on behalf of President Truman, asking them to restrict information in their publications about the atom bomb. The War Department was quick to state that this was not an extension of wartime censorship, which was officially slated to end that fall. Rather, the War Department directive said, it was simply a request that newspaper and magazine editors submit any material relating to nuclear matters to the War Department for review. It was an issue of “the highest national security” lest proprietary information about the bomb fall into foreign hands.

Starting around that time, there had also been a hastily assembled offense of government press conferences meant to put the press straight and set the American conscience at ease. Even before the occupation had officially begun, Charles Ross, press secretary to President Truman, had sent the War Department a memo suggesting a media event at the site of the July 16 atomic bomb test in New Mexico to show the public that there was no long-term radiation damage there, and absolutely nothing to worry about when it came to post-bomb aftermath. “This might be a good thing to do in view of continuing propaganda from Japan,” he wrote.

On September 9, Manhattan Project leaders General Leslie Groves and J. Robert Oppenheimer personally gave a tour of the New Mexico bomb testing site to a group of around thirty journalists. Even though the reporters were assured that there was barely any residual surface radiation, they all wore special white protective shoe covers, just to “make certain that some of the radioactive material still present in the ground might not stick to our soles,” one reported.

“The Japanese claim that people died from radiations,” General Groves told the reporters. “If this is true, the number was very small.”

The attending journalists toed the line. One New York Times correspondent, William Laurence—who also happened to be on the War Department payroll and had been “on loan from the Times to the atomic bomb project” since the previous April, as the Times put it in personnel records—reported that “the Japanese are still continuing their propaganda aimed at creating the impression that we won the war unfairly, and thus attempting to create sympathy for themselves and milder terms.” In the meantime, he went on, the New Mexico ground on which he had personally stood “gave mute testimony” that the “Tokyo Tales” of death by radiation were indeed fiction. Their Geiger counters had revealed that “radiations on the surface had dwindled to a minute quantity,” he added.

The U.S. government and the Manhattan Project principals actually had not known in advance what the full effects of their experimental weapons would be, and they now hustled to make private investigations in the “death laboratories” of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as one Allied correspondent later called them. They urgently needed to find out whether radioactivity was indeed lingering in the atomic cities and how it was affecting humans—not because the United States intended to help treat Japanese bombing victims, but rather because those cities were about to be occupied by American troops.

Just before giving his nothing-to-see-here New Mexico press event that September, General Groves had hurriedly dispatched Brigadier General Thomas F. Farrell, his Manhattan Project deputy, to Japan to survey the aftermath in Hiroshima. On September 8, General Farrell and a team of Manhattan Project scientists arrived in the city to make what one reporter later described as a “spot check” inspection. (Upon seeing the damage in Hiroshima, one attending American physicist thought that, to the average beholder, it looked like the handiwork of a thousand B-29s, but that the United States had instead “simply used a labor-saving device.”) From Washington, the pressure on General Farrell was intense, recalled a member of his team; General Groves continuously bombarded Farrell with indignant cables from afar, demanding updates. The team hurriedly concluded that “there had been a minimum of radioactivity in the city,” as most of it had been absorbed back into the atmosphere. Based on the Farrell team’s brief investigation, General Groves announced to the press that very few Japanese had actually died from exposure to radiation and that Hiroshima was essentially radiation-free.

“You could live there forever,” he said.

Once back in Tokyo, General Farrell held his own press conference at the Imperial Hotel to present his atomic city findings. He did concede that a few Japanese were now dying due to gamma ray exposure received from the blast on August 6, but that the reporting on Hiroshima had been exaggerated.

The conference was going well until the Daily Express’s Wilfred Burchett materialized, having just arrived from his “Atomic Plague” reporting trip to Hiroshima. He was dirty, exhausted, and sick. When he confronted the briefing officer, in front of a full room of reporters, about what he had seen in Hiroshima, he was told that “those I had seen in the hospital were victims of blast and burn, normal after any big explosion.” Burchett pushed him further on the strange illnesses now befalling blast survivors.

“I’m afraid you’ve fallen victim to Japanese propaganda,” he was told.

In the months that followed these early-autumn press conferences, General Groves continued his own PR campaign, an all-out effort to rebrand his nuclear creation as a merciful weapon. Summoned by Congress that November to testify about use of the bombs on Japan and their aftereffects, the general eventually conceded that radiation had been responsible for some of the deaths in the atomic cities, but informed the Senate Special Committee on Atomic Energy that doctors had assured him that radiation poisoning “is a very pleasant way to die.” During fall visits to Manhattan Project labs and industrial contractors, General Groves gave speeches in which he told his audiences that there was no need for guilty consciences over the atomic bombings. He personally had no qualms, he told audiences.

“It is not an inhuman weapon,” he told one audience. “I have no apologies for its use.”

For John Hersey and William Shawn, it was time to get behind the scenes. The government junkets, conferences, speeches, and suppressed reporting were having the desired effect: across the United States, protests and alarm had been subdued to a manageable murmur. The idea of the bomb as a reasonable mainstay weapon in the national arsenal—and a nuclear future in general—was becoming acceptable to the increasingly apathetic public. Many if not most Americans had moved on from Hiroshima and Nagasaki before the stories about what had happened in these cities had ever been told in full. To the New Yorker team, the true meaning of what had happened in Hiroshima and what the bombings portended for humanity had clearly not sunken in.

“[Too] few of us have yet comprehended the all but incredible destructive power of this weapon,” they concluded, and it was time for everyone to “consider the terrible implications of its use.”

Hersey and Shawn decided that Hersey would try to get into Japan and write about “what happened not to buildings but to human beings.” They didn’t know the exact angle yet, but they knew it had to be done. If the press corps in Tokyo either would not or could not undertake the story, the New Yorker would try. Shawn and his boss Harold Ross had already been prepared to run another such story earlier that year, when New Yorker reporter Joel Sayre crossed into Germany with Allied troops and planned to do a story on the decimation of Cologne from the point of view of the civilians living there during the bombing campaign. That story did not come to fruition—but its approach could and should be used for a Hiroshima investigation.

It was time to learn and reveal the reality of the bombs that had been detonated in the name of the country, democracy, and decency itself. It was also time to put individual faces and fates to the Hiroshima and Nagasaki casualties at last. Sterile statistics and interchangeable photographs of rubble had become the enemy of such truth telling; dehumanization of the Japanese victims was allowing Americans to be lulled into complacency about the weapon.

Throughout World War II, Hersey had seen how dehumanization had enabled the worst acts of the war. He had personally witnessed the “wanton savagery” of air attacks on civilians in Rome and evidence of Nazi atrocities at concentration camps. During the war, like many Americans, he too had seen the Japanese as an animalistic enemy, but even while under Japanese fire while covering a battle on Guadalcanal he had tried to remember that it was a man shooting at him—a son, possibly a husband, maybe a father.

“I had long hated the idea [of the Japanese],” he wrote shortly after the experience. The idea of the enemy was infinitely hateable, he stated. “But I did not hate this individual. Was he from Hakone, perhaps Hokkaido? What food was in his knapsack? What private hopes had his conscription snatched from him?”

The war—culminating in the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki—had revealed to Hersey the “depravity of man” and his ability to completely degrade fellow human beings. He had come to realize that “[if] civilization was to mean anything, we had to acknowledge the humanity of even our misled and murderous enemies.”

He began to plan his trip.

From FALLOUT: The Hiroshima Cover-up and the Reporter Who Revealed It to the World by Lesley Blume. Copyright ? 2020 by Lesley M.M. Blume. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

You Might Also Like