Scientists discover new way humans feel touch

Humans have an attuned sense of touch that connects us to our surroundings, and now, scientists think they've discovered a previously unknown way that we use this sense.

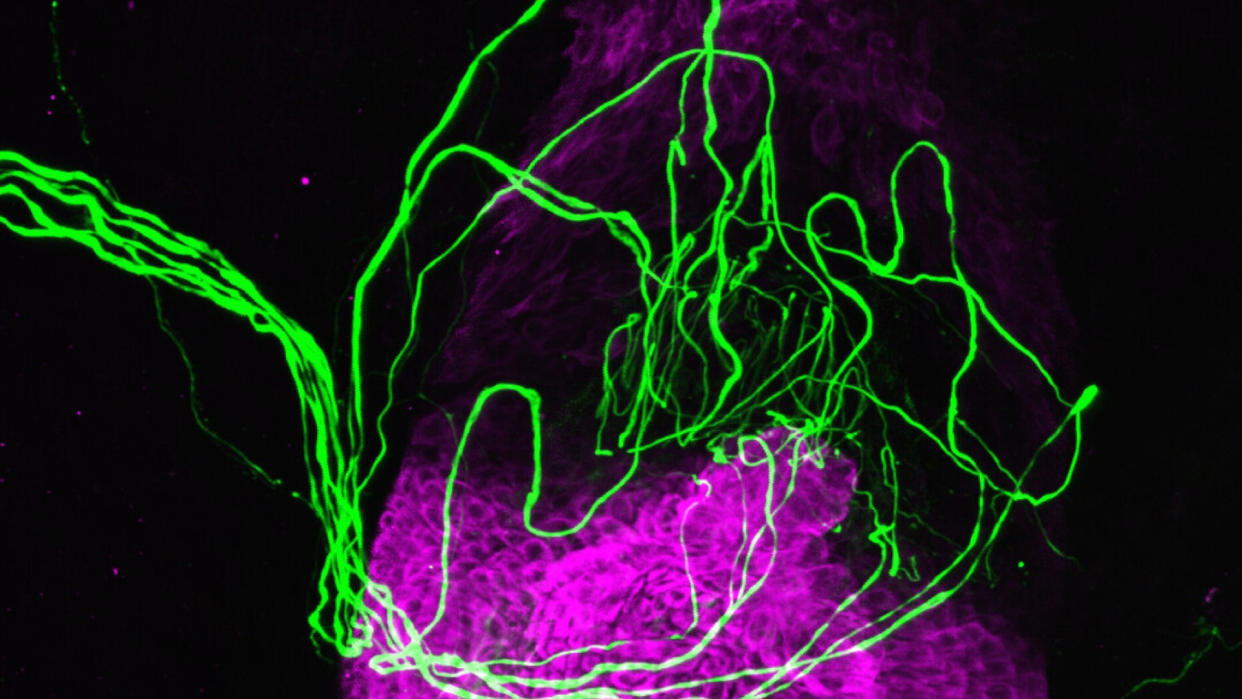

A new study has revealed that cells within the outer layer of our hair follicles, the tiny tubes in our skin that surround hair fibers, can detect touch. In response, these cells release chemicals called neurotransmitters that activate nearby sensory neurons, which relay information about our surroundings to the brain. It was previously thought that touch detectors were found only in nerve endings in the skin and near hair follicles — not actually within the follicles themselves.

The findings, published Oct. 27 in the journal Science Advances, were drawn from isolated cells and have yet to be proven in living organisms. However, if confirmed, they may expand the repertoire of known ways that humans sense touch, including via the activation of sensory neurons in the skin that detect both touch and the movement of hair.

"The mechanism we have presented is not better, or more sensitive than direct activation of sensory neurons, which is how we usually process touch," co-senior study author Claire Higgins, a tissue regeneration researcher at Imperial College London, told Live Science in an email.

"So, we are intrigued to discover what the hair follicle adds to the process of touch sensation and why it has this role," she said.

Related: The five (and more) human senses

In the new study, the researchers analyzed the gene activity of more than 40,000 cells isolated from human hair follicles and skin. They did this by looking at RNA molecules, which relay instructions for building proteins from the cell's DNA to its protein construction sites. They found that the hair follicle cells contained three times as many touch-sensitive receptors as the skin cells.

In a separate test, applying tension to human hair follicle cells that had been grown in the lab alongside sensory neurons led to the activation of the latter.

In another experiment, the authors discovered that hair follicle cells activated the nearby neurons by releasing the neurotransmitters serotonin and histamine, which also triggers inflammation. The skin cells also released histamine in response to touch, but not serotonin, and the authors are curious whether both the skin cells' and hair follicles' activation could be linked to skin diseases such as eczema. The skin condition is thought to be exacerbated by histamine-producing immune cells called mast cells, but perhaps these two types of touch detectors also play a role.

"Our work is the first to show that skin cells can also release histamine," Higgins said. "While the levels released are much lower than that released by mast cells, it still suggests a mechanism for skin cells in this disorder," she said.

This research is still in its early days, but as serotonin and histamine can influence each other's production and release in many parts of the body, this could represent a new therapeutic avenue.

RELATED STORIES

—How many cells are in the human body? New study provides an answer.

—New virtual reality suit lets you reach out & touch 'environment'

—Being extra-itchy may mean you're missing some cells

"We don't know if this relationship is mirrored in the skin, but if it is, we can explore ways of modulating serotonin as a way to regulate histamine release," she said.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to [email protected] with the subject line "Health Desk Q," and you may see your question answered on the website!