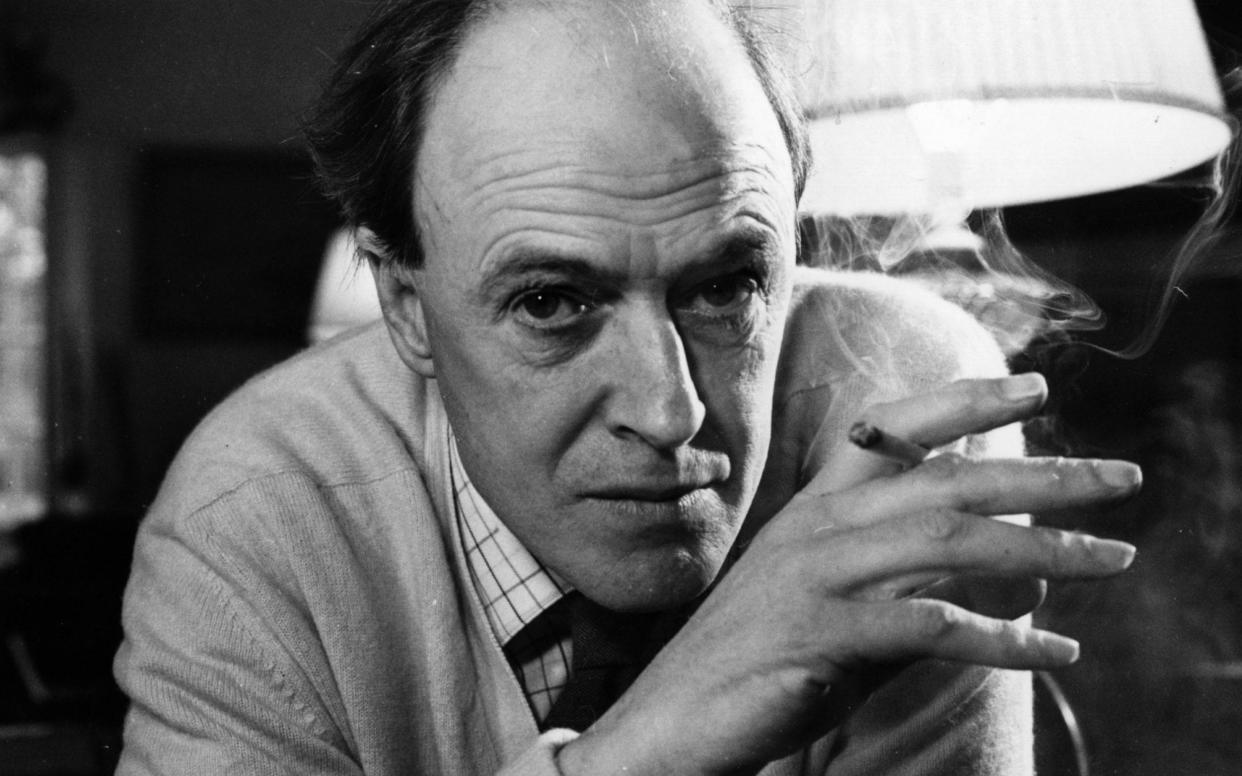

Roald Dahl's life was tainted by anti-Semitism – but his work isn't

Since Roald Dahl died 30 years ago, those who have wanted to celebrate his rich legacy have all tended to take the same approach to his anti-Semitism: ignore it. You won’t find any mention of the anti-Semitic public pronouncements of his final years in Fantastic Mr Dahl, Michael Rosen’s biography aimed at children; and until very recently the official Dahl website studiously omitted any mention of the controversy.

It now transpires, however, that at some unspecified point in the last few months Dahl’s family and literary estate have quietly snuck an “Apology for anti-Semitic comments made by Roald Dahl” on to an obscure corner of the website.

“The Dahl family and the Roald Dahl Story Company deeply apologise for the lasting and understandable hurt caused by some of Roald Dahl’s statements,” it reads. “Those prejudiced remarks are incomprehensible to us and stand in marked contrast to the man we knew and to the values at the heart of Roald Dahl's stories, which have positively impacted young people for generations. We hope that, just as he did at his best, at his absolute worst, Roald Dahl can help remind us of the lasting impact of words.”

Why make such an apology now? As a piece of reputational damage limitation, it doesn’t seem any more urgently required than it would have been 10 or 20 years ago. The Dahl brand continues to be phenomenally popular even in our cancel-happy times.

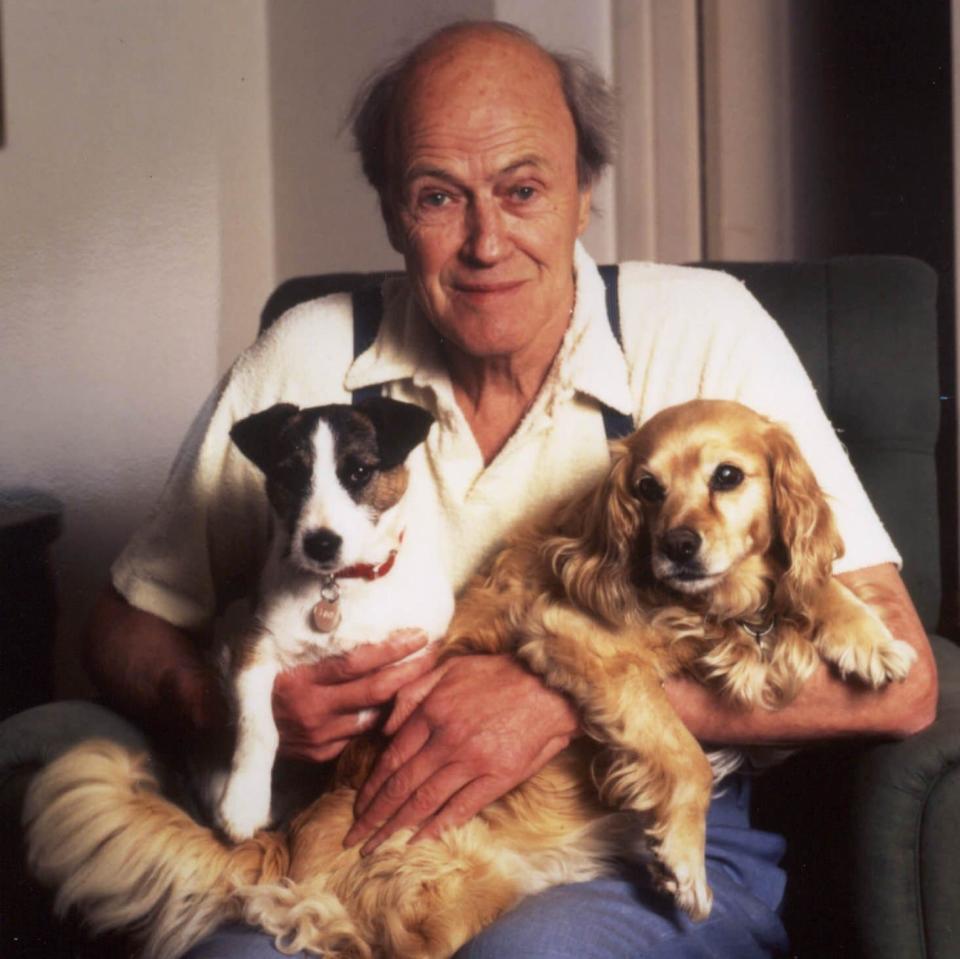

His books still sell - in greater numbers than they did while he was alive. Where once critics were sniffy about Dahl - many dismissing him as the literary equivalent of crisps and fizzy drinks rather than something more nutritious - he’s now accepted as part of the children’s literary canon, with johnny-come-latelys such as David Walliams measured against him.

Nor has his anti-Semitism put Netflix off embarking on a project in partnership with the Roald Dahl Story Company to make a slew of forthcoming adaptations, with the Jewish director Taika Waititi (Jojo Rabbit) set to helm two animated series based on Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

Most people are happy to separate the books from the author, it seems; it’s when efforts are made to celebrate Dahl as what the BFG would call a “human bean” that problems arise. This Christmas Sky One is broadcasting a drama called Roald and Beatrix: The Tail of the Curious Mouse, based on a real occasion on which Dahl, as a small boy, met Beatrix Potter, laying the foundations of his future work as a children’s author. The film has been described as a “Roald Dahl origin story”; one can see why a renewed focus on Dahl’s life as well as his work might lead his estate to think the time had come to address the anti-Semitic elephant in the room.

They may also have taken into consideration the fact that Dahl’s anti-Semitism pops up in the news cycle every few years - the last occasion was when the Royal Mint refused to honour him with commemorative coins during his centenary year in 2016, on the grounds that he was “associated with anti-Semitism” - and that each time it happens society has moved further away from tolerating and forgiving such transgressors. So the Dahl estate has probably been wise to take the initiative and emphasise that the brand is now in the hands of people who do not agree with Dahl’s more disgusting views or seek to defend them.

So how controversial were Dahl’s views and is he still in any danger of cancellation? When I first began to read about Dahl’s life, having devoured his books as a child, I was not surprised to discover that he was a difficult man who liked to shock people with his outrageous opinions.

If I try to think myself back into the mind of the small boy who read Dahl’s books over and over again until they fell to pieces, it is the nasty bits that come to mind most vividly: Aunt Sponge and Aunt Spiker being crushed to death by the eponymous fruit in James and the Giant Peach; Mr Twit, with malicious ingenuity, making his wife think she is shrinking by adding tiny pieces of wood to her walking stick and chair legs every day.

The message, totally different from any other book I had read, was that life is mostly cruel, so you might as well find the funny side of that cruelty and relish it. If Dahl had been a nice man, or a nice man all the time, I don’t suppose he would have been able to inflict such refreshingly transgressive views on his young readers.

Christopher Hitchens once wrote an essay examining the truth of the accusation that Dahl was an adulterer, bully and anti-Semite. “Of course it’s bloody well true,” he concluded. “How else could Dahl have kept children enthralled and agreeably disgusted and pleasurably afraid? By being Enid Blyton?”

And yet one starts to wonder how healthy Dahl’s fiction really is; not just how far did he draw on the dark places in his own soul, but how far did some of his more abhorrent views creep into his books.

He made several inflammatory statements in the 1980s, in articles and interviews, about Jews. Perhaps the most repellent of his assertions about Jewish people were that “even a stinker like Hitler didn’t pick on them for no reason” and they were easy to kill en masse because “they were always submissive”. He told one interviewer: “There is a trait in the Jewish character that does provoke animosity, maybe it’s a kind of lack of generosity towards non-Jews. I mean, there’s always a reason why anti-anything crops up anywhere.”

In a piece he wrote in 1983 about the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, he claimed that “Our hearts bled for the Lebanese and Palestinian men, women and children, and we all started hating the Israelis”, just as “our hearts bled for the Jewish men, women and children, and we hated the Germans” 40 years previously. In fact there is some evidence that he “started hating the Israelis” (in the original draft of that article he wrote “Jews” but the editor changed it) long before the 1980s.

Dahl sometimes peddled Jewish stereotypes in his fiction. His biographer Jeremy Treglown notes that in his first novel, Sometime Never (1948), “plentiful revelations about Nazi anti-Semitism and the Holocaust did not discourage him from satirising ‘a little pawnbroker in Hounsditch called Meatbein who, when the wailing started, would rush downstairs to the large safe in which he kept his money, open it and wriggle inside on to the lowest shelf where he lay like a hibernating hedgehog until the all-clear had gone.’” There is also the short story “Madame Rosette” in which the title character is described as “a filthy old Syrian Jewess”.

Perhaps the most insidious example of Dahl’s anti-Semitism was his screenplay for Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968). For this film Dahl invented a character who did not appear in Ian Fleming’s original novel - The Child Catcher.

The mannerisms of Robert Helpmann’s performance, combined with his black hat, long black coat and huge pointy nose, suggested a Jew who seemed to have taken on the role of a Nazi, exercising power over a town in which children are not permitted to live and dragging those whose hiding places are discovered off to be imprisoned. Nowadays the film’s inverse Holocaust parallels are seen as insensitive at best and at worst a deliberate stirring of the anti-Semitic pot.

Dahl’s own books for children are not notably anti-Semitic, although one has to wonder what they would have been like without the restraining hand of his editors. His publishers cut racist and misogynist content from Matilda (in which the title character was originally not a proto-feminist heroine but a “devilish little hussy”), The BFG, The Witches and the Charlie Bucket books. The delightfully naughty Dahl we all enjoy is a watered-down version, made palatable by publishers who knew that cask-strength Dahl would be beyond the pale.

Dahl still has high-profile defenders, even among the Jewish community. Steven Spielberg, who directed the recent film of Dahl’s The BFG, has said that “nothing in anything he's ever written has held up a mirror to some of the statements he made in 1983... I don't truly believe somebody with such a big heart, who has given so much joy and so much epiphany to audiences with his writing, was an anti-Semitic human being.”

So it could be argued that the occasional incidents of anti-Semitism in Dahl’s work were fairly mild, certainly by the standards of his generation, and that the foul things he said in later life were just a complicated old buffer’s misguided attempts to show off and stir up mischief. This may explain why his children’s books are happily free of the poison of racial prejudice; but of course the fact that he may not have really believed in some of his nastier remarks hardly excuses him, and did not prevent him from causing real pain to some of his young fans.

In April 1990 he received a letter from two San Francisco schoolchildren that read: “Dear Mr. Dahl, We love your books, but we have a problem... we are Jews!! We love your books but you don't like us because we are jews. That offends us! Can you please change your mind about what you said about jews.”

Dahl sent a message back saying it was injustice he hated, not Jews; but you can see why his estate might be eager to mitigate any similar pain felt by Jewish readers today. I hope that his children’s books will always be allowed to inspire delight in young readers; but it would certainly be wrong to pretend that he was not a malign figure in some ways, or that we shouldn’t think carefully about the ways in which we choose to honour him.