How Roald Dahl’s family tragedy inspired Willy Wonka

Long before Willy Wonka locked himself away behind the huge iron gates of the biggest chocolate factory in the world, becoming a reclusive figure of rumour and magic, he was a dashing and penniless ingénue with dreams of establishing a chocolate shop in Paris. At least, that’s the story according to the new prequel, Wonka, in cinemas now, in which Timothée Chalamet plays Roald Dahl’s maverick inventor in his youth with such wide-eyed, guileless sweetness, one wonders if he has sugar running through his veins.

Those with a strong attachment to the playful streak of sadism that characterises Willy Wonka in Dahl’s beloved 1964 novel might wonder whether they have wandered into the wrong film. Yet the big-hearted character of Chalamet’s Wonka, whose Parisian capers are entirely co-writer and director Paul King’s invention, is perhaps not so far removed from the Willy Wonka Dahl first conceived when writing, in the summer of 1960, what would later become Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

Five drafts of the original novel are known to exist, and four of them (the first is lost) are housed with the rest of the Dahl archive at the Roald Dahl Museum, in Great Missenden, close to the house that Dahl and his first wife, the actress Patricia Neal, moved into in 1954.

What’s clear from the first surviving draft is that Dahl initially regarded Charlie and the Chocolate Factory not as Charlie’s story but as Wonka’s. “From the outset, Wonka the inventor was very much at the forefront in Dahl’s mind,” says Steve Gardam, director of the Roald Dahl Museum. “You get only the bare bones of his character in this first draft. Yet what’s immediately apparent is his brilliance and his kindness.”

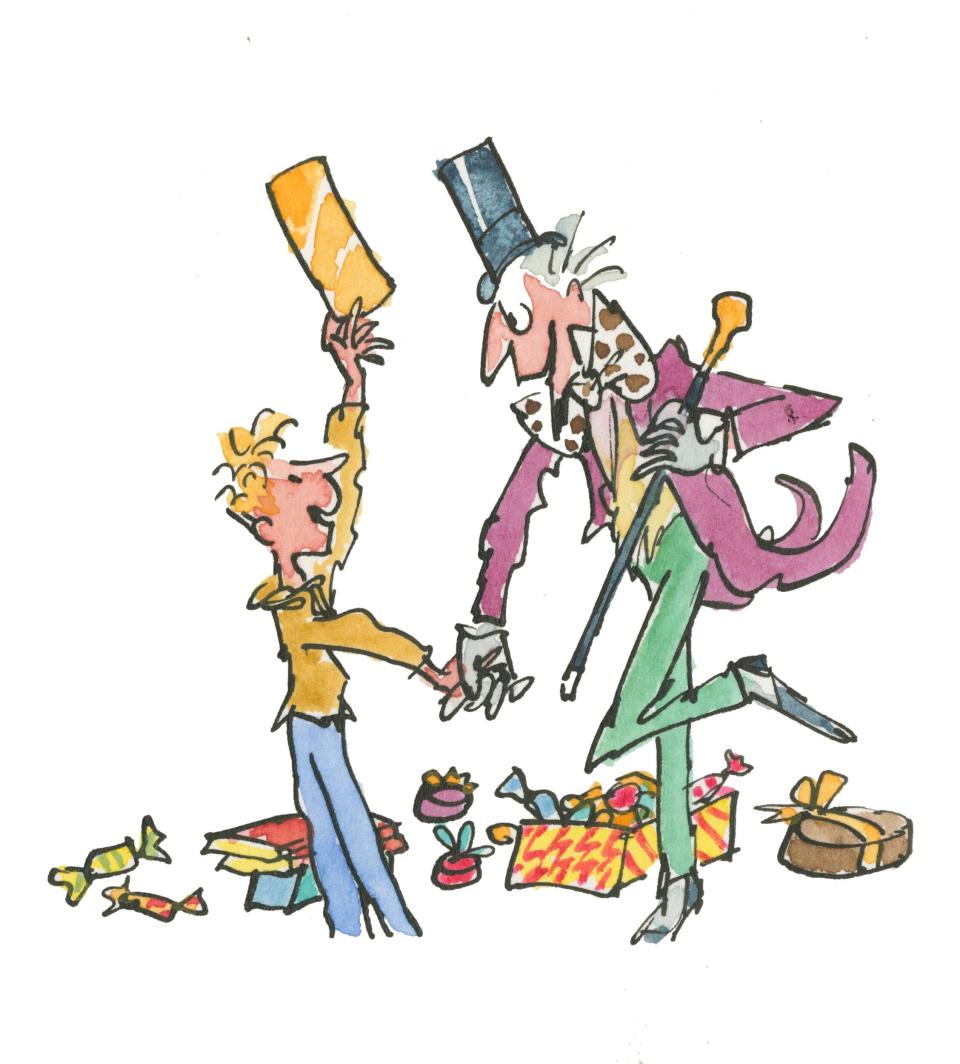

That first draft, which has never been published, presents Wonka on the very first page, flaunting his silk hat and cane, and accompanied by a list of his astonishing achievements: the chewing gum that never loses its taste; the lovely blue birds’ eggs that leave a tiny pink sugary baby bird sitting on the tip of your tongue. He’s a family man, married with a son. He is not remotely secretive, throwing open the factory doors to whoever wants to visit.

And he is a man of ostentatious generosity, gifting to a very rich man an Easter egg containing a model village made of chocolate, where tiny marzipan people can be seen behind the windows. He then makes a life-sized 10-bedroom house for an even richer man, featuring hot chocolate pouring from the bathroom taps (a story that reappears almost word for word with the palace Wonka builds for Prince Pondicherry in the published version), although his warnings to eat it before it melts fall on deaf ears. When the man finds himself swimming in a “huge brown sticky lake of chocolate”, Wonka, we are told, goes into his inventing room and invents for him a chocolate that won’t melt. Later, he produces a wood where the “leaves were made of mint crisp and green sugar” for a lady who whenever she was hungry would chop off a branch with an axe.

Dahl came of age during the great boom in chocolate-production techniques. In the 1930s, Cadbury’s would send prototype chocolate bars to Repton School, in Derbyshire, where Dahl boarded between 1930 to 1934, to test before they were manufactured. (Dahl apparently rated one as “too refined for the common palate”.)

As a boy and a self-confessed chocolate obsessive, Dahl was, argues Gardam, confronted with evidence of the surely miraculous: bubbles pushed into chocolate to produce Aeros; chocolate manipulated into folds to produce Flakes. “It led Dahl to imagine there must be a room in the chocolate factory where someone would be inventing extraordinary new forms of chocolate,” Gardam says. “In this first draft, you can see him introducing the idea of an inventing room in the very first paragraphs.”

Yet, in a semi-tragic twist, Dahl would soon become an inventor himself. In 1960, his four-month-old son, Theo, was hit by a cab while in his pram during the Dahls’ trip to New York. He was sent 40ft in the air and suffered a shattered skull, which resulted in hydrocephalus – when fluid accumulates in the brain. With the help of a neurosurgeon and, staggeringly, a toymaker, Dahl developed the Wade-Dahl-Till drain in 1962, which was so effective at draining the fluid, the trio sold it, not-for-profit, all over the world. “We produced this splendid little valve,” said Dahl. “Most precise. It had to be non-return, open at a certain pressure, not clog up.”

It’s hard to separate the creation of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, which is dedicated to Theo, from the tragedies that befell Dahl during the writing of it. The first surviving draft was preceded by a now-lost version Dahl had written just before Theo was born, which told the story of a little boy who, on visiting a chocolate factory, falls into a vat of chocolate. He turns into a chocolate figure, is sold to a shop, and eaten by a little girl. It apparently failed to charm Dahl’s young nephew and Dahl presumably threw it away. (Dahl was an inveterate user of the wastepaper bin, often writing in pencil and then screwing into a ball the first page of each new story up to 150 times.)

He produced the first draft that survives after Theo had recovered from his accident. Called Charlie’s Chocolate Boy, it contains the same beginning and a similar outline to its lost predecessor, with Charlie intriguingly described as a “little negro boy”, a detail removed in later drafts at the request of Dahl’s agent. This time, Charlie, still encased in chocolate, is taken to Mr Wonka’s house as a present for Wonka’s son, Freddie, where he foils a robbery and is given a chocolate shop by Wonka in gratitude. Yet, not long after he finished the story, Dahl and Neal’s seven-year-old daughter, Olivia, died from measles. It took Dahl a long time to embark on a third.

Later versions reveal what we now know as Charlie and the Chocolate Factory slowly emerging into glittering focus, like Wonka himself emerging from the depths of his factory after 10 years in isolation. The golden-ticket scheme is introduced, with first 10 children shown round the factory, then seven, then the five we have today. In the first surviving draft, Dahl describes a factory peopled not by Oompa Loompas but by “7,384 [ordinary] men and women”.Wonka gradually transforms, too, losing his unambiguous, benevolent charisma to become a tricksier, sinister, morally ambivalent figure.

In his 1994 biography of Roald Dahl, Jeremy Treglown argues that an early version of Willy Wonka appears in Dahl’s 1943 children’s story The Gremlins, inspired by Dahl’s experiences in the RAF and in which gremlins – impish creatures who are part of RAF folklore – join forces with RAF pilots to defeat the Nazis.

“The Leader of the Gremlins is a prototype of Mr Willy Wonka … [ruling] whimsically over an underground kingdom, alternately bullying his subjects and appeasing them with sweet fruits called snozzberries,” Treglown writes. He also suggests that it’s tempting to regard Wonka as an avatar of Dahl himself, saying that, in person, Dahl often behaved like “an actor, a ringmaster, a spell-binder: Mr Willy Wonka”.

None of this is remotely the concern of Paul King’s Wonka, of course. For, having gripped the public imagination for more than 60 years, and been immortalised on screen by Gene Wilder in 1971, Wonka lives most vividly in the eye of the beholder. “If you look now, you can see Mr Wonka quite easily,” reads the opening paragraph of Charlie’s Chocolate Boy. If ever a sentence captured the seductive power of Dahl’s most mercurial creation, surely this is it.

The Roald Dahl Museum is open Thursdays to Sundays; roalddahlmuseum.org