The Road: 100 Days of Travel in Pandemic-Ravaged America

I lost my mind during the plague year. The fact that my country also lost its mind was of little comfort.

Maybe you lost your mind too. There were so many opportunities. Maybe you were hiding from an invisible virus in an oppressive New York apartment, listening to the sirens all night long. In the morning you went for a bike ride through vacant streets and came across a hospital where they were stacking bodies like cordwood. Or maybe you were sheltering-in-place in a small town, Zooming and doom-scrolling into the abyss, trying not to get called a communist by the no-mask mafia. And then you got a call: The one person who made the world make sense was gone.

More from Rolling Stone

My breakdowns were different. I have a Brooklyn friend who hasn’t been to Manhattan since March. That’s not me. No, my meltdowns were mobile. Hotels were closed, airports were cleared out, and the borders sealed, but I still spent 100 days on the road in 2020. Here’s the butcher’s bill: 16 states and five countries; 12,000 miles behind the wheel; another 30,000 in the air.

Memories were made: Passing out in a Qantas lounge shower at Heathrow. A Detroit woman describing the loss of her mother, aunt, and grandmother to Covid-19 as church bells rang. Shouting questions at Al Gore about the disappearing Earth outside a Davos restaurant ladies room. A dear friend disappearing before my eyes in a Chicago nursing home. Marching with Greta Thunberg in Stockholm with a 103-degree fever in February. Wondering if I gave her the virus. Not knowing if I had the virus. Tearing the fuel panel off my Hyundai SUV at the Beach, North Dakota, Flying-J Truck Stop, staring at the metal and saying, “That was stupid, my friend.” Drinking with 20 maskless Trumpers at a dive bar in downtown Tulsa, knowing this was more ill-advised than what happened in Beach, North Dakota.

I didn’t set out to experience the dystopian version of the American road trip resplendent with Rapid City, South Dakota, bed bugs and nine nights in Tulsa. It just happened.

Well, that’s not exactly true. As a reporter, I’ve chosen a profession where no one comes to you. Don’t get me wrong — as a politician might say, it is an honor and privilege to do this for a living. I have talked with great men and men on death row, sitcom stars and a shark-tagging woman. All of them have helped me understand better my own ridiculous trip on this big blue marble. An appreciation for my job has only grown stronger as the death of print, true-crime podcasts, and a pandemic have decimated my profession. I now feel like one of a half-dozen dodo birds whose survival has more to do with chance than skill. I’ve watched the greatest minds of my generation reduced to writing branded content. And, yes, I know I could be coming up with zingers for the Lands’ End catalog by Memorial Day. So I hit the road to report on a 2020 election disfigured beyond recognition by a pandemic. Uh, I also had the idea that no one would dare fire me when I’m in North Platte, Nebraska. Right?

Some of it is personal. My father was a Navy pilot. I went to school in six different towns before high school. He was deployed six months a year until he was deployed permanently, killed in a plane crash off the USS Kitty Hawk, not far from Diego Garcia. Whether by nature or nurture, I’ve inherited his happy feet, a quarterback rolling out of a perfectly fine pocket for a scramble that sometimes ends with a concussion.

I’ve leaned into it. My running bit on the Twitter Machine is about Hampton Inns, where I always request a top-floor corner room, which I almost always get because I have Platinum Silver Ultra Something-or-Other status. As a purported grown-up, I’ve lived in six different cities before moving to Vancouver two years ago. It hasn’t come without a price. I can land in Austin, London, Detroit, or Tampa, Florida, and have dinner with a pal that night. Somehow, I have confidants in Indianapolis and Glendale, California. Alas, in Vancouver I know no one outside of my wife, son, dog, a kind Israeli scientist, and the Jethro Tull fan who is papa to one of my kid’s classmates. It can get fucking lonely.

Still, 2020 was going to be different. (This was even before the plague hit). I was going to meet people in Vancouver. Maybe volunteer at a soup kitchen. Pass on my lack of soccer skills to six-year-olds as an assistant coach. I’d recently turned 50 — OK, not that recently — and the nonstop travel had shifted in my own narrative from swashbuckling storyteller to the old guy at the college kegger. In January, I drove aimlessly after interviewing a screen icon and pledged to myself that I would spend more time with my dear wife, perfect son, and Peanut the Wonder Dog. I felt old, and there were people who needed me.

“You do not want to die in a Hampton Inn,” I said aloud.

At that precise moment, I was running up the 101 to Malibu, 1,200 miles from home.

I’m a one-man enterprise, but there are satellite offices. I have a spare pair of Sambas and a ragged but presentable Barneys dress shirt in Anacortes, Washington, Los Angeles, and in a Chicago high-rise, just in case I drop in on a whim, which is likely to happen a half-dozen times in a year. Icy and cold in NYC? Use some air miles and head with just a backpack to JFK and on to Burbank Airport, where I can be down the stairs and in a rental car in 13 minutes. I have become America’s Guest, trading anecdotes about Lindsay Lohan and Johnny Depp in exchange for a spare bed and access to your Wi-Fi password and all the Trader Joe’s taquitos in your fridge.

But 2020 presented a challenge. Covid-19 was shutting down the world. I had to stay in one place. The choice wasn’t mine.

Turns out I underestimated myself. Any addict knows there’s a way to get a fix when you need it.

One of my favorite memories before the plague hit is a simple one. A boy in a red hoodie, with a giant smile, sits in a faux airplane with a slightly nervous woman in a leather jacket behind him. It is my son and my wife. It is February 7th and we are at Legoland in California.

We are 38 days into the year and I’ve already spun out a car chasing a Pete Buttigieg event in New Hampshire. Jane Fonda has clutched her dog closer to her chest in West Hollywood after I asked an impolitic question about her departed brother. Today, I’m back from covering Davos and the annual conference where rich people try to fix the world without it impacting their richness. It was all a jet-lagged daze: Graffiti in the railway station proclaiming “Eat the Rich.” Crowded restaurants where pretty young things talked about Trump’s speech moving the markets. Waiting an hour to get into Anthony Scaramucci’s wine party and questioning all my life choices. Scaramucci! Not ordering the horse meat served on a slab of heated rocks. The endless line of black sedans belching filth into the air at an alleged climate conference. The horse pasture turned into a helo lot. Wondering what the fuck the point of it all was.

But that was all over. I am back in American reality, featuring cotton candy and a bric-a-bloc representation of a New Orleans funeral march. A bunk bed in a pirate room awaits. There are kids. So many fucking kids. There’s an evening disco, where the kid dances with his favorite Ninjago character- —Lloyd, Kai, Dareth? — while parents drink rotgut wine out of plastic glasses. The boy is happy, so I am happy.

Then it hits me. I start feeling achy as I drive them back to LAX. I have a spare two days in L.A. before flying to Stockholm via London. I’ve scheduled an interview with Greta Thunberg, the hardest “get” this side of Jungkook. The trip is on, it is off, and then back on. I’m starting to feel terrible, but I dare not cancel, it’s the cover story for Rolling Stone’s climate issue. Besides, it is probably just bronchitis, a chronic illness for me. I try to sleep after takeoff, but a bone-rattling cough hits me over Greenland. Covid-19 is just a whisper, but there’s still the flu or whatever bug has cried havoc in my lungs, so I spend most of my time in the bathroom trying to keep my germs in a confined space.

We land in London. My clothes are soaked through with sweat. I have four hours before my connection and I stumble through the international terminal until I find an airline lounge. I pay the grievous fee and within minutes I’m in a private shower sitting on a stool. I grip the safety rails. I turn on the cold water. It feels good.

That’s the last thing I remember until I hear a sharp rapping on the door. An old woman tells me my 30 minutes is up. I crack open the door, and I can’t tell if she is worried for my welfare or convinced I’m shooting heroin into my toes. I put back on my clammy clothes and stagger to my connection. I land in Stockholm and the night is winter black. I flag the first car I see and climb in the back. It turns out to be a bandit taxi, but even the chiseler driver is concerned. He asks me if I want to go to a hospital. I say no, just take me to the Hilton. I nod in and out until we pull into the hotel driveway. He charges me an amount in kroner that in the morning I realize is the cost of three nights at my hotel.

I get to the room, fall on the bed with my shoes on, and everything fades. I awake in my clothes to the phone blaring. There is that familiar heart-attack feeling of not knowing what country you are in, much less which city. An elf is on my chest pounding me with his brass-knuckled hands.

I thought I had 24 hours of grace, but it turns out that Greta is only available today. In two hours. There is little I can’t endure professionally with the aid of Coca-Cola, Imodium, and some legitimately prescribed amphetamines. I take a tablet and pour some Cokes from the executive lounge into a coffee pot and guzzle it like a Norseman drinking blood out of a skull. (If that is a thing).

It’s Valentines Day and couples hold hands in Stockholm’s old town. I find Greta in the town square. She’s 17, but still seems like a tween in a purple winter coat. The one thing we have in common is exhaustion, but she is young and wears it better. It turns out she isn’t just physically tired; she is exhausted with my country. A winter hat pulled down over her matted hair, she patiently outlines why even the Green New Deal, an ambitious plan with no chance of passing a GOP-controlled Senate, doesn’t go far enough. I ask her about her now-famous stare-down with Trump at the 2019 Davos conference. “I can’t think about him too much,” she told me. “I would have no energy for anything else.”

Soon it was time to march, but what she says stuck with me throughout the whole year. It’s important to note this was still pre-pandemic and Trump’s America had already exhausted the rest of the world. The march ended in a square on the other side of the city, next to a Burger King. Feeling better, I craved onion rings, but found myself stuck next to a talkative middle-age Swedish dad who had brought his kids to this children’s crusade. We struck up a conversation and I told him that I was American. He chuckled a bit.

“I wonder if you get tired of always having to explain your country to everyone you meet.”

The winter sun had already dropped below the Baltic when I made it back to my room. The Ritalin, caffeine, and adrenaline wore off and I crashed, whipping myself with self-recrimination: Why was I here? Why had I flown when I knew I was sick? Wasn’t there a better way to make a living? How the fuck was I going to turn a 56-minute conversation into 4,000 words?

I listened to my interview with Greta through headphones. I’d asked a classic People magazine question: What did we need to do to save the planet for her and her children? She didn’t answer in jargon about zero carbon emission and banning fossil fuels. Maybe it was her Aspergers, maybe it was my exhaustion, but I hadn’t digested her answer in real time.

“We don’t need to have the biggest car, and we don’t need to get the most attention. We just need … ” She paused for a moment. “We just need to care about each other more.”

I cried for a while and then slept for two days.

A couple of weeks later, as Covid-19 was moving from the international page to the evening news, I found myself in one of my safe houses. Hunter and Beth Ware’s home in Anacortes, Washington, is about two hours from mine in Vancouver. It has everything my crowded town house does not have: space, a view, an endless assortment of Costco’s hermetically sealed hard-boiled eggs, and no toddler day care, with a dozen tykes screaming in French and English.

Hunter was a Navy pilot like my father, and he was a main character in a book I wrote in 2013 about pilots. His family had become treasured friends. The Wares now lived about 20 miles from where I spent the last of my childhood before my dad was killed in a plane crash. For years, the area around Whidbey Island, the last place I’d lived with my father, had been a dead zone for me, but the Wares helped me reclaim it for my own. Their daughters were in college and their home had a room named “Stephen’s Guest Room” that included a placard with my name on it next to the bed, accompanied by a glass of vodka and cranberry, my favorite libation. I came here to write, eat, and- — when everyone was at work -— do my Risky Business dance as Pavement blasted on their sound system.

I’d known Hunter for a decade, and the first half of our friendship had been spent talking about life and other shit from Bahrain to NAS Jacksonville to the command center of the USS Lincoln in the Persian Gulf, as he monitored Iranian fishing boats through binoculars. But that was all over for Tupper, his call sign in the Navy. He was now retired, had a good job that he could ride his Harley to in 20 minutes, and a perfect home where I was always welcome. All the transience of his deployments and multiple duty stations were at an end, he now had a solid home base, and something I still didn’t have even though we were contemporaries. Now in Vancouver, I saw myself driving down and siphoning off a flake of his permanence for decades to come; with dozens of cookouts ahead of us mixed with good natured cursing as he tried to turn my boy into a Dungeon & Dragons enthusiast.

And then he and his wife told me they were moving. Their girls were grown and their parents were getting older on the East Coast, so they had taken a transfer to Newburyport, Massachusetts, a town not unlike Anacortes, but a five-hour flight away. I tried to be happy for them, but made several hundred bitter comments on our last weekend together. The morning I was to leave, I looked at a copy of The Seattle Times and saw a headline about the first American death from Covid-19. A virus I had first heard about a month ago in a European airport, on the way to Davos, was now here.

The Wares knew it too. Their moving truck was coming tomorrow and they were driving east, trying to stay ahead of the epidemic. I don’t do denial very well, but I did that day. I gave them hugs, got into my car, and pretended like I would see that house again. I never did.

Then it hit. Deaths across Washington state. Then New York and New Jersey fell. Rolling Stone closed its offices. I live 3,000 miles away but it was still a stomach punch. I came up with the idea that the magazine could do a series of interviews on something called Zoom with actors, politicians, and musicians about how they were spending their time in lockdown. This made me feel useful for about six days.

The border was sealed, a not-so-discrete message that Canada understood that the United States didn’t know fuck all what it was doing. My son’s school closed, as did the lap pool, the rare place where I could quiet my yammering brain. Every day, we would take my boy into the Vancouver gloaming to kick a soccer ball or play Red Light, Green Light. One day, my wife filmed him doing a rap and dance, his coordination sadly inherited from his father:

It’s all about teamwork

We must come together

Work together

It’s all about teamwork

Shut up, he’s six. And he was right. It was about teamwork and my country did not have it. Instead, there was a man with Bozo’s hair telling us to shoot bleach into our bones and that masks were for the beta people. There are only a few things I remember about those first few months besides Trump spewing nonsense every afternoon. I watched every episode of 30 Rock. I listened as my best friend told me his catering business was disappearing in L.A. I heard fear in the voices of my friends in New York. Still, I didn’t know anyone who had Covid-19; the pandemic seemed unreal, something happening on the other side of a two-way mirror.

That didn’t last. I read that Covid-19 had probably started in America much earlier, perhaps in Southern California back in January. I thought of my California-borne illness and it checked off many of the boxes — the chest pain, hacking cough, the gasping for air, etc. … At first, I was horrified. Had I been a superspreader on my Stockholm trip? Then Greta tested positive. Had I almost killed off the world’s best climate hope? (I did the math and she likely caught the virus weeks after I left. I hope.)

But that thought passed and my brain did a proud kick turn into rationalization. If I’d already had Covid, I could get back out on the road! (This was back before anyone thought you could get Covid twice.) It was now May, too late for a test, so there was no way to tell for sure, but I didn’t care. And as an American with a Canadian wife, I could cross the border with impunity. Well, not impunity — I would have to quarantine from my family for two weeks in our basement when I returned, but that was down the road.

Maybe I was just another white guy believing in my personal American exceptionalism, but it seemed important and not just for my travel itch. I tell other people’s stories for a living just like a dentist pulls teeth.

Or so I told myself. I wouldn’t fly. Instead I rented a Hyundai SUV and crossed the border at Blaine, Washington. I headed east. There were just 2,000 miles to go. The next morning, I got my hair cut at a Supercuts in an Idaho strip mall. The world was on fire, but I felt better.

On my way out east I stopped in Emigrant, Montana, a town not too far from Yellowstone National Park. Like every middle-age white guy, I’d fallen in love with Montana, except I didn’t fish or hunt; just listened to Jason Isbell a lot. I sat at a desk in an Airbnb with a view of the Madison Range and tried to finish a piece on America’s fascination with UFOs. This story seemed important before Americans started dying by the thousands. I had to make a call for the piece. The old man on the other line was kind and exchanged all kinds of alien information. But he was ill and housebound, and really wanted to know what was going on out in his country.

“What are you seeing? How is it out there?” asked Harry Reid, formerly U.S. Senate majority leader. I didn’t know what to say except mumble.

“I sure as hell wished you were still in charge of the Senate instead of the toxic reptile from Kentucky.”

Reid laughed softly.

So, how was it out there? The thing about spring Covid was that it was everywhere and nowhere. Montana hotels were open, but you had to get your fried chicken from a takeout window. I gave a worried man 10 bucks so he could drive his truck from Livingston back home to Butte. He had been waiting a month for his unemployment benefits to kick in. A few hundred miles away, a friend sold his Jackson Hole apartment in record time for an obscene profit. The gash between the affluent and desperate in America had never been deeper.

The road was no different. On a Saturday in May, I took the Beartooth Highway through Yellowstone’s mountains. Yellowstone’s west entrance had just opened up after a pandemic close and I drove on an empty road past ghost lodges, where road signs compelled you not to stop or get out of your car. (I did once, to say hello to a herd of buffalo. It was the right thing to do.)

Beartooth is often described as the most beautiful road in America, but as I hit 11,000 feet I had renamed it the “scariest as fuck” road in America. My head ached from the altitude and the seemingly endless twists and turns.

Then I came around a bend to a clearing and saw a remarkable sight: There were cars parked on both sides of the narrow road. Kids slalomed the road on skateboards while skiers in shorts and anoraks hiked up a glacier for a last run. I got out of my car and promptly sank up to my groin in wet snow. Thankfully, I was wearing linen shorts. A bearded dude did doughnuts on his snowmobile. Up the road some old bastards were fishing through the ice. I beamed even though my testicles were frozen. After 90 days of darkness I’d found a glimpse of magic America in all its joy and idiocy.

It should be said there was not a mask in the whole bunch. It was a time when the Mountain West remained untouched by the virus. It was a time that would end soon enough.

About an hour later, I hit the town of Red Lodge, Wyoming, still bobbing up and down in my seat, rocking out to a Conan O’Brien podcast. The sun was out and a grandfather and grandson in matching overalls were hard at work in a front yard. It was straight out of Norman Fucking Rockwell. I looked again. They were hammering in a Trump 2020 sign. I pulled into a gas station where I got some reception. I checked a Covid-19 tracking site for the latest statistics. There were another 1,171 Americans dead. I drove on.

I was headed for Michigan to report on the Covid tragedy there. Gov. Gretchen Whitmer had issued stay-at-home edicts to save lives, particularly in minority communities where the plague effortlessly skipped from house to house and church to church. Whitmer’s opponents reacted by storming the capitol in $40,000 SUVs, brandishing rifles, and demanding their right to haircuts and Buffalo wings. This was 2020 America.

There was a side benefit: I could check in with my mom, who lived all alone just outside of scenic Flint, Michigan, the city we moved to after my father died. I tried my best to stay safe on my drive or as much as a middle-age man with a weakness for curly fries could. A trucker friend warned me that rest areas were Covid hot spots and should be avoided. A buddy drove from Iowa to L.A. in a van, living on Imodium and excreting into a slop bucket. Like many things Covid, there was no evidence at the time whether you could die from using a Kalamazoo urinal, but I avoided them. Sort of. I pissed behind dumpsters in rest areas if I could get away with it. That is, if the rest areas were open. My stomach is weak and so is my resistance to Arby’s. I once emptied my bowels on a deserted farm road, my only companions being hand sanitizer and a Hilton hand towel.

The farther I got away from the coast, the more I hit seemingly sensible white people offended by my mask, even though it was quite stylish and had been made from leftover scraps of Liberty of London fabric. I stopped for gas somewhere in Big Ten Country and a lady at the next pump noticed my Canadian license plates. “Oh, honey, you don’t have to wear a mask here.” When I left it on, she stared with dead eyes and slammed her gas tank shut. Then I hit the industrial Midwest around Minneapolis and Chicago, and the masks came back into style.

Around the same time, George Floyd was murdered. I tuned into AM radio from Minneapolis and debated detouring, but wasn’t sure what another reporter could add to that tragedy. Instead, I watched a half-dozen kids in Ashland, Wisconsin, hold up Black Lives Matter signs in a town that consists of 0.5 percent African Americans. But for every positive reaction there was a negative one. The next day, I slowed for a deer in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, only for the buck to seemingly dive for the back quarter of my SUV. He popped up and then reeled into the bushes like a drunk at last call. Traumatized, I pulled into a nearby rest area and told a woman smoking while walking a dog what had happened. She dismissed me with a wave of her cigarette. “You have to speed up or those dumb fuckers will kill your car.” I could not help but look at the back bumper of her truck: Trump sticker.

I finally reached Detroit and checked into an Embassy Suites, Hampton Inn’s slightly more upscale uncle, which was now affordable, since who wanted to stay in a Michigan hotel in May? The manager told me occupancy was running at about 15 percent. I looked down from the top floor into the atrium, and out the window at the idled Chrysler corporate headquarters across the road, and I could see a state dying.

Not that the state had a choice. By the time I’d arrived, Michigan had already lost 7,000 citizens, largely black and urban. It was here that I found a country on the brink of some sort of civil war consumed with county-by-county fighting. One day, I drove over to Hamtramck in Wayne County to visit with Biba Adams, a black Detroit writer who had lost her mother, aunt, and grandmother to Covid-19. On the radio, a WJR morning jock bleated about the dangers of George Soros and the authoritarian regime that Michigan Gov. Whitmer was creating in the state. Biba and I sat outside and she told me about her family; loyal Chrysler employees, gospel singers, and beloved movie partners. Now they were all gone. It was her birthday.

Rachel Elise Thomas

That afternoon, I left Biba and drove 33 miles to New Hudson, a predominantly white suburb. I stopped at the New Hudson Inn, a bar populated by Harleys and a stand selling corn dogs and cotton candy. Nearby, a telephone pole holds a stapled poster with a picture of Whitmer, hands in shackles, with the words “Lockdown for All, But Not for Me.” I met with Brian Cash, a long-bearded ardent right-wing protester who kept saying ‘Fuck Whitmer’ when he wasn’t asking me if I had rolling papers so we could share a saliva-laden joint.

Back in Hamtramck, Biba and I marveled at how white Michigan was approaching the plague.

“It’s a privilege not to have anyone affected,” Adams told me. “Because if they did, they would be in a panic. They certainly wouldn’t be worrying about their hair.” African Americans make up only 14 percent of Michigan’s population but accounted for 40 percent of the state’s Covid-related deaths. To Adams, that meant the rest of Michigan could check out: “If it’s a black problem, it’s no problem at all.”

Naturally, other Michiganders disagreed. Spoiler alert: They were all white dudes. In Milan, Michigan, I met with a man with a giant Ron Paul poster on a wall and a semi-automatic mounted nearby. He told me of a friend’s restaurant that had been closed down just before St. Patrick’s Day, his buddy’s biggest revenue day. He then told me the restaurant had recently reopened now that the virus had temporarily faded. I asked him how his friend was doing. He snorted and sneered. “He asked me to wear a mask and I left.”

It took all of my limited professionalism to not call him an asshole and leave. But as I drove away, I wondered what had happened to my country, where men saw death all around and their conclusion was it was a power grab by the governor, who had a perverse desire to see her state’s unemployment hit 20 percent. None of it made sense. I headed back to Detroit for a peaceful walk near Wayne State featuring black clergy and Gov. Whitmer. The chants and songs were uplifting, but my first thought was they all were about to be roasted by the right for not social distancing, even though they were all masked and outdoors, where the virus spreads much slower. I was depressingly correct: The memes were up before I got back to my car.

I felt low, so I stopped in to see my mom, who lived about an hour way in the somewhat embarrassingly named Grand Blanc. Maybe she could help me make sense of the madness. This was somewhat ironic because I’ve built a large part of my design for living on the premise that my mom never made sense.

We sat on the deck of her house, where she had remained isolated for three months. Her little rat dog provided her immeasurable solace, even if he made me contemplate canine homicide. But she seemed of sounder mind than almost anyone else I’d met on my drive. She told me of her neighbors who helped her with snow plowing and leaves. They seemed supernice, but one night the lady let slip a Michelle Obama joke involving an ape and my mother stopped her. “You make another joke like that and we can’t be friends,” she told her. If you knew my mother, a confrontation-resistant child of the South, you would know how remarkable this was to me.

I never wanted to hug her more. But I couldn’t.

“The world has gone crazy,” Mom said. “Just completely crazy.”

Courtesy of Stephen Rodrick

A few days later, I found myself in Tulsa for the now-infamous Trump rally. A day after I arrived, a civil-rights group was carrying an empty casket to City Hall as a protest against the historic loss of land rights for black Americans. The procession found itself on the other side of a chain-linked fence separating them from Trump supporters who were already in line for the Donald’s Saturday rally.

Two men in Trump T-shirts smiled wickedly and held their fire until the pallbearers were out of earshot.

“Hey, is Al Sharpton in that coffin? Is that why it takes six of you to carry it?”

Now, I’m no Sharpton fan. In fact, I once wrote 6,000 words on how he is a scam artist who ruined lives with his lies about the Tawana Brawley case. Still, I moved toward the fence line with fists clenched. A stranger grabbed me.

“It’s not worth it.”

He was right, of course, and the two dudes melted into the crowd. I’ve rarely felt such rage in my life. Maybe it was the right-wing radio I listened to on the 15-hour drive, first as a joke and then as an obsession, counting how many times a white guy could say, “We all know this epidemic will end the day after the election.” Or maybe it was getting booted out of the downtown Hampton Inn because the Secret Service had requisitioned the whole place, including the breakfast bar. The hotel was nearly adjacent to the BOK Center, where Trump would speak on Saturday, so I was sent over to the Tulsa Club, a stately hotel where the staff had big smiles; the rally had doubled their hours.

Why was I here? A large part of it was my chronic case of FOMO disease. This was Trump’s first major rally of the pandemic and general-election campaign. Hundreds of thousands were expected. Could be the gateway to a second term or a second wave of death. Or maybe both! Who knew?

Expecting passion, I found the emptiness of American ideology that had moved from the quiet corners and empty spaces online to the mainstream. One morning, I found myself in front of two sixty-ish women in Q T-shirts at Jerry’s Deli in downtown Tulsa. I asked them what it all meant. They smiled like door-to-door evangelicals and asked me if I’d heard the good news about the return of JFK Jr. and an America that would be united by Donald Trump. The funny thing is when I asked for details — why JFK Jr., for instance — they just kept smiling and telling me it was all out there on the web.

I didn’t find the American spark of revolution, just sedated Americans high on their own fantasies. I was heading back to my hotel the night before the rally when I stumbled upon a large man in an American-flag polo shirt and matching floppy hat chatting up a summer-solstice wizard.

“I’m here for the history,” said the man. “This is the first time in American history where a president has just said ‘Fuck you’ to the doctors and scientists.” Tim Lilly was the gentleman’s name and he had driven up from Dallas to sell flashing American-flag pins for five bucks.

The markup was only 40 percent, so he had to sell a lot of them to break even. I’ll admit, I was a bit drunk, having dipped into a dive bar for two shots of vodka to help me forget I’d prioritized another America-in-Decline shitshow over my family. By now, my logic was in the toilet because if I really wanted to be there for my boy I would not be drinking in a bar filled with unmasked Trumpers who had been sleeping on the street for 48 hours. Lilly was persistent in closing the deal.

“You buy one and I’ll sing ‘The Battle Hymn of the Republic.’ ”

I bought and he sang. Not bad.

I then asked him about his history theory.

“Trump is putting it all out there. He’s going to be right or wrong,” Lilly told me. His cherubic face lit up like one of his flashing flag pins. “We’ll know in three weeks!”

He anticipated my last question. “I know, I should be concerned because I’m heavyset.” He shrugs. “But I’m not.”

The last I saw of him, he was walking past a woman in a “Make the Democrats Shit Their Pants” T-shirt.

The next morning, I walked over to the press check-in to pick up my credentials with the idea of not going into the actual pit of Covid, but the line was so long I headed back toward the outdoor festivities adjacent to the arena. I was just going to hang for an hour. Before I knew it, my temperature had been taken; I was given a bracelet and pushed toward a stage, where a band was murdering “Hallelujah.” (Poor Lenny Cohen!)

An hour later, the doors to the arena opened, and I joined the mild crush of humanity. I still wasn’t planning on going in, and when I reached the entrance I told security that I didn’t have a ticket.

“Oh, you don’t need a ticket. C’mon in.”

I sprinted to the upper deck for some social distancing, promising myself I’d skedaddle once it started to fill up. I had an hour or two to kill. I FaceTimed with my wife. I did a lap around the arena and saw Herman Cain walking to his VIP seats. (Cain would die of complications from Covid-19 just six weeks later.) I ate two hot dogs. And just before Donald Trump spoke, I tweeted a 12-second video of the empty blue seats in the upper deck, and it got 8 million views.

Courtesy of of Stephen Rodrick

After the rally, I waited at a downtown Domino’s for a pineapple and ham pizza. It took a while. When I walked out, pizza box under my arm, sirens were wailing. On the corner, Black Lives Matters protesters blocked a bus full of National Guard soldiers leaving the area. I saw a young couple in Trump caps looking scared, the tiny teenage girl squeezing her boyfriend’s hand. A young black woman saw the two and approached them slowly. “You guys will be OK.” She pointed up toward a less-congested street. “Go that way and you can avoid all the mess.”

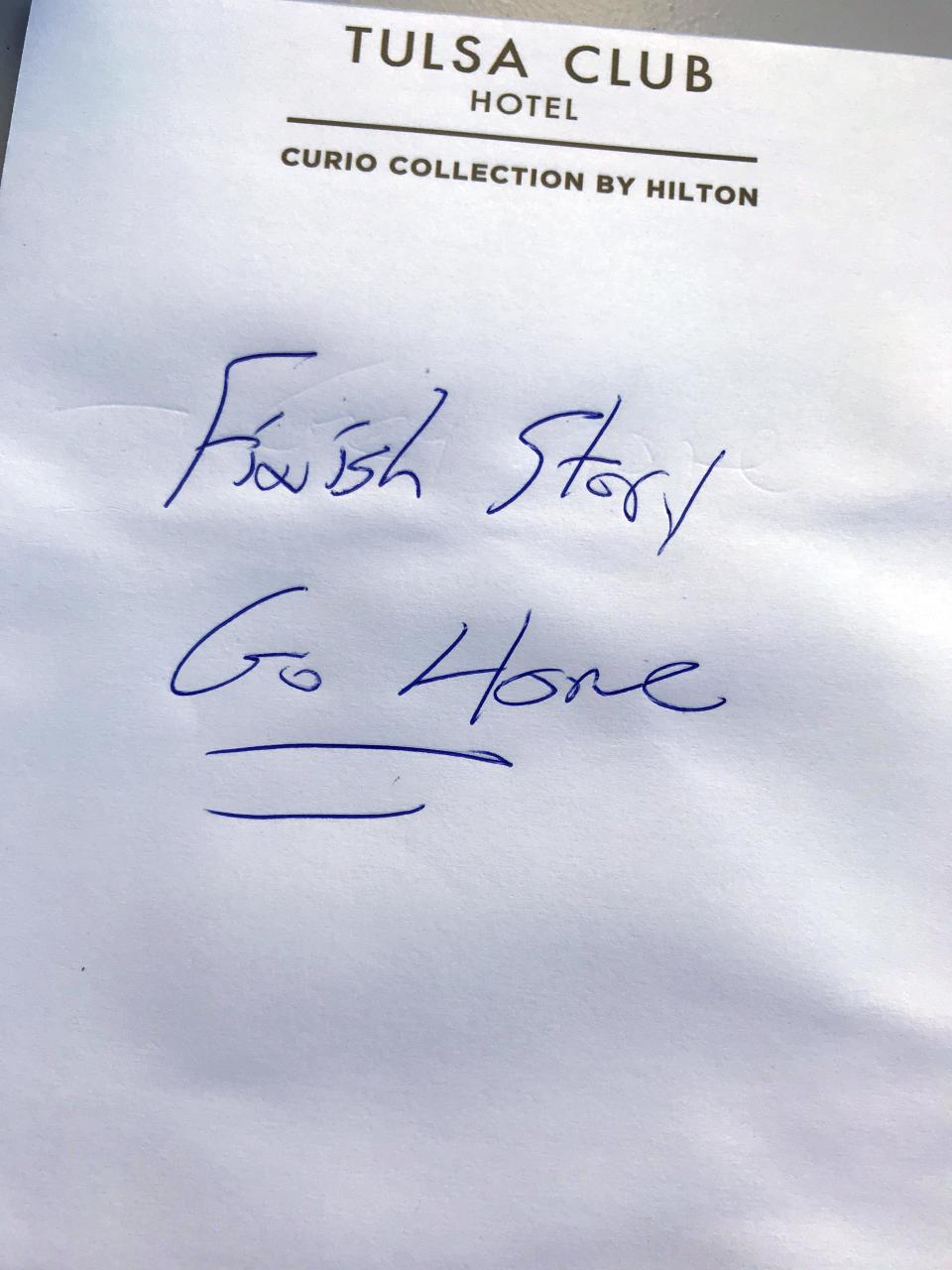

I stayed in Tulsa for another week writing up a dispatch from the front and finishing my Michigan story, the hotel clerk saying hello every morning with a combination of kindness and pity. I wrote on a scrap of stationery “Finish Story and Go Home.” But I write slowly. Downtown was deserted with the exception of the occasional teenager on a scooter screaming down 4th Street. I felt ancient.

Repeatedly, I thought of the black woman’s moment of humanity. I wondered why, until it struck me: I’d seen like-minded people being kind to their own communities and hateful with men and women who looked different and didn’t share their view that Covid-19 was a George Soros-inspired hoax. The black woman saving the scared couple was the only time I witnessed anything that resembled actual grace.

She got me through the week.

I drove home on a combination of highways and back roads. One day, I wasn’t sure what state I was in until I emerged off a dirt road near Edgemont, South Dakota. I took a turn and found myself before a small YMCA with an outdoor pool. I couldn’t believe my luck. I got out of my car with my trunks in hand. Through the fence, I was met by the glare of two mothers paddling with their young children. Rarely, have I felt more unwelcome in my own country. I got back in my car and drove away.

The next morning, I reached Wyoming and pulled off the highway and into Little Bighorn Battlefield Monument. The night before, I’d done a little research on Gen. George Armstrong Custer, the architect of one of the great military disasters in our history. Custer was a skillful media manipulator who was losing his famous long locks and took elaborate steps to hide it from the public. I stepped out of my car and as far as I could see there were grave markers of Americans, their only fault was swearing allegiance to an egotistical man convinced of his own greatness.

Some things never change.

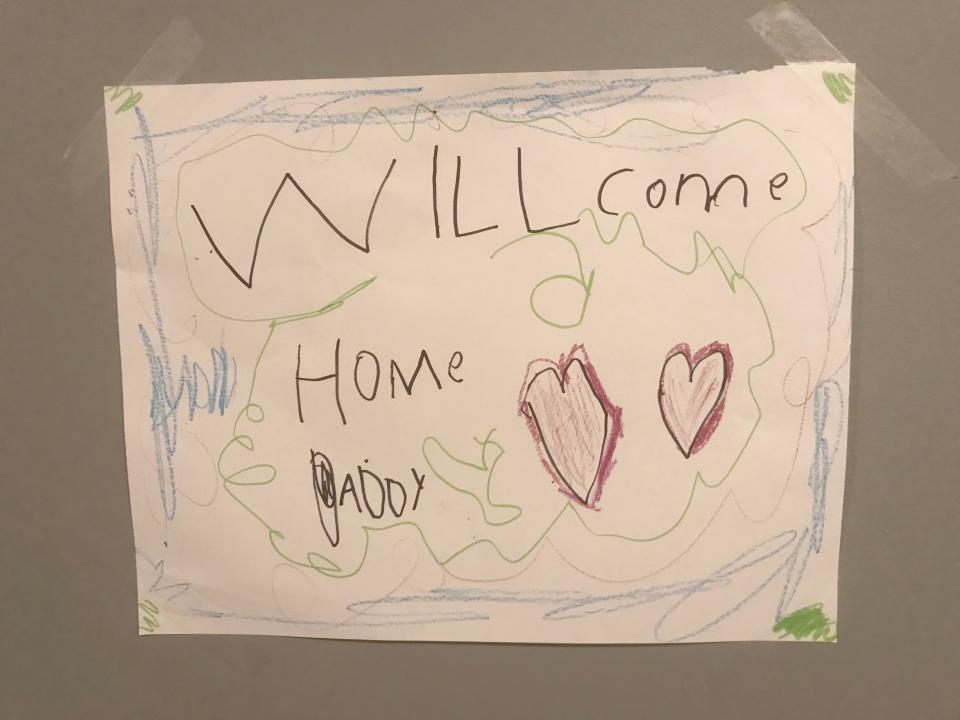

My re-entry back home wasn’t easy. The Canadian government mandated I isolate myself from my family in a separate room for 14 days. I bought a mini fridge and a two-burner and became the weird guy on his porch grilling up steaks for breakfast in his boxer shorts. I talked to my son and wife from a responsible distance and mostly slept and rewatched Justified. The only book I could muddle my way through was Timothy Snyder’s Bloodlands, an account of the millions slaughtered by Hitler and Stalin in Eastern Europe during World War II. This was my mood.

Eventually, I finished the 14 days and I went to the beach and the Okanagan Valley with my family. But I couldn’t stop thinking of what was happening without me. I did a video interview with Michael Cohen, Trump’s personal lawyer. I felt dirty talking to him, giving a Trump facilitator, who was released from prison because of Covid-19, publicity for his book. Many of his answers seemed rote — he was doing a lot of press — but he told me one thing that stuck with me: His old boss would not exit the stage gracefully.

“He will say that the polls were rigged or the ballots were tampered with,” said Cohen. “He will file lawsuits and call for a recount. He won’t stop.”

The man knew what he was talking about.

Courtesy of Stephen Rodrick

I ended up back out on the road in September. This time the destination was Youngstown, Ohio, where Trump had abandoned autoworkers whose jobs he had promised to protect. The pandemic was in a temporary repose and the highways were busy with families on the road. I drove around Youngstown and listened to the terminally ill Rush Limbaugh decide to spend his last days spitting invective about the Biden family. I met with Ohio Sen. Sherrod Brown, who tried to convince me Ohio was sick of Trump’s hatred and was going to go blue. I wanted to believe him, but Halloween was approaching and I drove past a Republican’s house that had a dozen or so skeletons holding Trump flags. There was no nod to the pandemic. These folks are too far gone, I thought to myself.

I wasn’t completely without blame. I wore my mask in all the right places, but ripped it off in frustration while interviewing a destitute former GM worker. His years on the factory floor had left him partially deaf and my mask muffled my voice.

Other letdowns were just selfish. I watched Trump and Biden debate on a TV in a Youngstown country club’s cigar lounge, chomping down an ahi tuna salad and multiple vodka tonics. I finished eating and slid down into my leather lounge chair, thoroughly enjoying Trump’s meltdown, my friend and I too giddy to put our masks back on.

Eating food out of a Styrofoam container was getting me down. One of the tragic-comic aspects of being a constant traveler is having a favorite haunt in almost every town. Youngstown was no different, and between conversations with workers left with little hope, I could be found dining most nights at Station Square, just off of Interstate 80 and adjacent to my hotel. Maybe I’d given up or was emotionally exhausted, but I started to dine inside, ordering prime rib, throwing my arteries into the game of slow Russian roulette that I was playing with my life. My meal was served to me at the bar in a Plexiglas construct that resembled a hockey penalty box. There was even entertainment, an old man singing “Slow dancing, swaying to the music,” accompanied by a Casio keyboard while no one swayed and no one danced.

The scene reminded me of the French phrase fin de siècle, roughly meaning “end of times.” Or so I thought. I ordered another drink and Googled the phrase. It actually means “end of the century.” I decided to cut myself a break and ordered one last drink.

It was my birthday.

I finished the story and drove west a couple of weeks later, stopping in Chicago to see my second parents. Steve and Kathy had informally adopted me more than 30 years ago when I was dating one of their daughters. I split up with the daughter, but kept her parents, the dad an ophthalmologist, the mom the kindest woman I’ve ever met. They had an art-filled house in Barrington, a horsey Chicago suburb and a pied-à-terre on Lake Shore Drive. They taught me about Jim Dine and French toast made with challah bread. They were secular Jews who decided I was their favorite gentile after I entertained them by doing a Jesus-on-a-raft routine, where I would float in their pool and say, “I say to you this day, we will be together in paradise.” (As I got older and thicker, I’d do “Jesus, the Vegas Years.”)

They nicknamed me ‘the Nice Boy,’ of which another daughter tartly observed, “The thing about the nice boy is, he’s not always nice.” That was true.

The best thing I can tell you about how them is that they love me unconditionally and forgave me all of my sins. I once flushed a half-dozen paper towels down their toilet rather than go downstairs and throw them out. Not long after, a pipe burst and water gushed onto their Norwegian-wood floors. There was $30,000 worth of damage done that they initially were going to pin on their house cleaner before I came clean in a river of tears, telling them how much their family had done for me, and I paid them back by acting like a child.

They laughed and forgave me. I was 35.

I visited them three or four times a year, sometimes staying for weeks, watching football on the weekends as Kathy boiled lobsters or roasted a duck. But that world was going away. Steve had a stroke and Kathy was forced to sell the big house. I stopped by before the sale was final. I watched the algae float on the surface of the untended pool where we once laughed so much.

Steve wasn’t doing well, he had been moved into a rehabilitation center in the city, where he refused to do his exercises, constantly asked where he was, and wondered why his wife had not visited in months. The facility had been shut down to visitors for months because of Covid-19, and I thought of Steve trapped in a body that had betrayed him and a mind that taunted his loneliness.

Finally, conditions improved enough that Kathy could visit. Three times a week, a nurse wheeled Steve out onto an outdoor patio where he could have visitors as long as everyone wore masks. No touching was allowed. One day, Kathy brought me along. I hid behind a pillar for a moment as Steve was wheeled out, and then Kathy shouted, “It’s the nice boy!”

Steve seemed confused, and then a look of recognition came into his cloudy eyes and he began to cry.

“I can’t believe you’re here.”

I gave him a T-shirt I liked; he always stole my T-shirts. I said I’d left all the lights on at their house, a long-standing joke, but his eyes faded out and he lingered between awake and sleep. We left after a half-hour and Kathy settled behind the wheel of her car, with me in tears on the passenger side. She spoke quietly: “Everything goes real quick. You should go home and see your family.”

So I did.

Courtesy of Stephen Rodrick

I got home and had to quarantine again. I spent a lot of time wondering why I always had to be on the move. I hated when my dad was gone, but now I had a six-year-old and I was doing the same thing to him, although he seemed not to care as long as his iPad battery was charged and Minecraft was open for business. Was I repeating the sins of my father on my own son? Can we learn nothing from the mistakes of the past?

I watched the election returns and talked to my mom semiregularly. She had a series of ailments that neither my sisters nor I could ascertain as either serious or just the aches of age. We were loathe for her to go see her doctor for a nonemergency reason, as Covid-19 was again raging across Michigan. Then, she called me one afternoon and her speech was slow and slurred. I panicked and called the sister who lives near our mom, and she drove over. A few days later, my mom had a CAT scan and it turned out that she probably had a mini stroke, serious but treatable.

I wanted to drive out to see her, but my passport was in the process of being renewed. I couldn’t go. For the first time, I understood how the rest of America felt as the world remained frozen.

Another month passed and the familiar squirrely feeling set in. In British Columbia, Covid-19 didn’t seem real. And I don’t mean unreal in the sense of, say, 20,000 motorcyclists pretending it didn’t exist as they made their way to Sturgis, South Dakota. No, schools were open here and a modicum of normalcy existed because Canada had taken the whole nightmare seriously: Citizens were paid to stay home and there wasn’t an ideological debate over wearing a mask unless you were from Alberta, the Oklahoma of Canada. The downside to this was it made me feel like I was wasting my time: There was a pandemic just a few hours away and I needed to get out there, to prove I mattered to myself and, perhaps just as much, mattered to my employer.

I came up with another story: a Plains state was exploding with Covid cases. Meanwhile, that state’s governor was shouting “We’re open for business” in a very Trumpian way, even as the state’s Covid-per-capita rate jumped to one not matched anywhere else in the world.

I had it all figured out in my head. I’d hit some casinos, the center of mask deniers, before finding a nurse or doctor overwhelmed in some forgotten town.

My editor stopped me. He pointed out that, as I’d scheduled it, I’d be in a Covid hot zone spending Thanksgiving alone and missing my son’s seventh birthday. The editor wouldn’t have it on his conscience.

He was right. If I learned anything in 2020, it was the importance of work-life balance. I desperately needed some downtime. So I canceled my trip.

Actually, I rescheduled it. I leave on New Year’s Day.

Best of Rolling Stone