Review: The Boy And The Heron Is A Gorgeous Movie Made For Someone Else

The Boy and the Heron hugging scene

I saw Studio Ghibli’s latest film, The Boy and the Heron, today. It was said to potentially be Hayao Miyazaki’s last film, created as a goodbye to his grandson before the 82-year-old passed. That shows in the final product. It’s a deeply personal film, from one person to another, and because I’m not one of those people, it’s left me feeling a little bit conflicted.

The Boy and the Heron starts with one of the most striking scenes ever committed to film. Mahito Maki, a young boy, is living in World War 2 Tokyo with his family, when a bombing hits the nearby hospital where his mother works. He sprints through a crowd of people, desperate to save his mother, only to watch her go up in flames.

Mahito sprinting through the streets, with very little sound, very little dialogue, just a boy running towards a raging fire, desperate to save his mother — it’s a heartbreaking, brilliantly directed scene. It only lasts for a few minutes, but if those few minutes were the entire film, I’d give it full marks in an instant.

GKIDS

What follows is a tale of grief, suffering, war, acceptance, and lots of birds. Like, so many birds. There’s the eponymous heron, of course, but also a bunch of hungry evil pelicans, a militaristic army of parakeets, and more that I’m probably forgetting. I don’t want to get into too much detail, I’m trying to avoid major spoilers as much as I can, but I can say with certainty that there are a lot of birds.

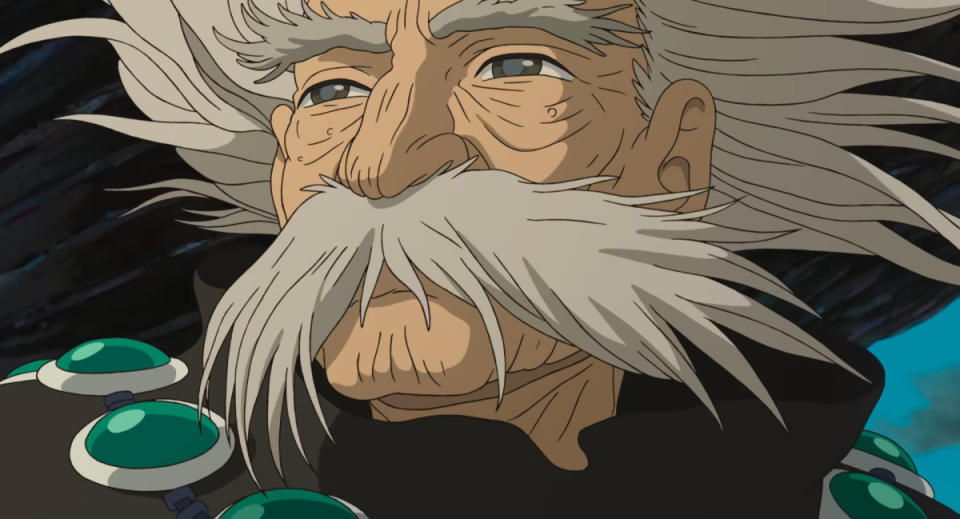

Outside of the birds, the film is absolutely drenched in metaphor. Some of it is quite subtle and obtuse, but there are some moments that are so incredibly on-the-nose that it’s honestly quite incredible to see. One scene towards the end of the film has Mahito’s great uncle asking the boy to take over his profession, saying that only somebody of his bloodline who’s free of malice can do the job. It’s a scene very clearly written by Miyazaki to his grandson that I almost felt uncomfortable watching it.

You know how, when somebody you know is upset or having a very serious, very sad conversation with another person, you sometimes just feel like an awkward bystander? You’re just kind of standing there, watching the saddest moments of people’s lives unfold, unable to offer comfort because it’s not your place, not your story. You want to help, somehow, but you can’t, really. It would be imposing.

That’s what watching The Boy and the Heron is like. It’s a touching, heartfelt goodbye from one incredible man to a grandson he loves so very much. And we, in the audience, are just the bystanders, watching it unfold.

I think that discomfort is somewhat intentional. I was acutely aware of this film’s purpose from the moment I went in, and who it was for. I knew it wasn’t for me, or for you reading this, or for anyone except that one person Miyazaki holds so dear. Miyazaki must have known that it wouldn’t resonate with everybody, or even with most people, but he made it anyway, for one person in the whole world.

Studio Ghibli

It’s hard to recommend The Boy and the Heron because of this. It’s not a bad film, not in the slightest, but I’m not the target audience, and neither are you. It’s filled with gorgeous animation, a subtle, simple soundtrack, and some of the most incredible visuals you’ll see in any animated film. If any of that appeals to you, then you should absolutely watch it. But you should know going in that this film isn’t for you, and treat it gently because of that.

I can’t, then, speak much to the story. I wouldn’t want to spoil anything, but I also can’t really fairly judge it either. It’s a story, from start to finish, that tells a very specific and very personal tale. It’s Miyazaki at his most self-indulgent, it’s deeply strange, and it’s probably steeped in cultural understanding and heritage that I as a white person who lives and was born in Australia cannot possibly fathom.

One thing that stood out to me, though, is the powerful use of silence. Dialogue is minimal at best, with characters speaking what they absolutely need to and not a single word more. We’re left with long stretches, up to 10 minutes at some points, where nobody says a word. It’s just beautiful visuals, a single piano, and imagery that will be burned into your brain forever. Silence is surprisingly hard to get right in film and TV, but The Boy and the Heron makes it feel effortless.

One final note is that I watched it with the English dub. I would have preferred to watch the Japanese dub – my local cinema was showing both, but did not indicate which was which – but I was pleased with the result nonetheless. Robert Pattinson put in a remarkable performance as the heron, and Luca Padovan brings a powerful, restrained performance as Mahito, but the real standout performance is from Florence Pugh as Kiriko. Watch the film in Japanese, if you can, but these performances are excellent and deserve to be heard too.

Studio Ghibli

I truly wish I had more to say about The Boy and the Heron. It’s a movie that will be running through my head over and over again for quite some time. In a few days, weeks, months, or even years, my opinion of it might change. I might rewatch it and it’ll suddenly click, or maybe more coherent thoughts will build themselves up in my brain over time. Right now, all I can say is that this strange, beautiful, and awkward movie is unlike any piece of art I’ve experienced in my life.