Remarkable things you probably didn't know about Georgian London

Having already revisited medieval and Tudor London, we’re stepping back in time to explore the 18th-century capital – and highlighting what remains today from the era.

Vauxhall was synonymous with pleasure

Today it’s a fairly drab part of the wider metropolis, but during the Georgian period this spot across the river from Westminster was known for its pleasure gardens, an expanse of trees, shrubs, footpaths, fountains and follies. Thousands, from all walks of life (so long as they could afford the one shilling entrance fee), came each evening to gossip, stroll, buy food and drink, watch concerts and firework displays, and even ride in a hot-air balloon. It displayed paintings by Hogarth in its supper booths, making it effectively the country’s first public art gallery.

Things got a little less respectable at night, when prostitutes, criminals and pickpockets entered the fray. “Despite efforts to keep ‘the riff-raff’ of the city outside its elegant gates, Vauxhall had a slightly louche, dubious reputation,” explains Danielle Thom, a Museum of London curator. “Its wooded groves and shady alleyways were the perfect place for a discreet assignation, and the well-dressed prostitute was associated with the garden to the extent that London print-shops sold images with titles like ‘The Vauxhall Demi-Rep’, showing beguiling ladies in expensive but revealing clothing.

“One of the most scandalous events at Vauxhall occurred at a fancy dress masquerade in 1749, when the courtier Elizabeth Chudleigh arrived ‘dressed’ as the classical figure Iphigenia – her costume consisting of nothing more than a thin scarf draped over her body, showing off more than it hid. Again, the press and printsellers had a field day.”

Equally impressive was Ranelagh Gardens. It boasted a pavilion in the fashionable Chinese style and a spectacular rococo rotunda, where a nine-year-old Mozart would perform in 1765, as well as a more refined clientele. “It has totally beat Vauxhall,” gushed Horace Walpole soon after its opening. “You can’t set your foot without treading on a Prince, or Duke of Cumberland.”

But there were no public toilets

So how did the revellers at Vauxhall, with a bladder full of sherry, spend a penny? Alas, there were no public loos as we know them today – so most people simply found a quiet corner. Venetian Giacomo Casanova even remarked at the frequency that he spied “the hinder parts of persons relieving nature in the bushes” in London’s parks and gardens.

Danielle Thom adds: “The very wealthiest patrons, who arrived by carriage and were accompanied by servants, would have been able to retreat discreetly to their carriages or a private nook and make use of a chamberpot, but for most visitors to the pleasure gardens, there was no pleasure at all in answering the call of nature. As was the case with so many aspects of London... the glittering surface hid a rather nastier reality.”

Debauchery was rife

With the Puritans forgotten and the dour and pious Victorian age a long way off, Georgian Londoners had a penchant for promiscuity – little wonder that the country’s first venereal disease clinic, London Lock Hospital, opened at Grosvenor Place in 1747.

Covent Garden, dubbed the “Square of Venus”, was one of the city’s seediest corners. “It was the very sink of vice,” writes Dr Matthew Green in his fantastic book London: A Travel Guide Through Time. “Blind fiddlers were in high demand as they’re perfect for orgies, unable to name and shame clients. In 1776 one man would hire out a room at the Bedford Arms for a scored orgy with four prostitutes. When it was finished, he promptly shot himself in the head.”

There was even a Yellow Pages for sex workers, Harris’s List of Covent Garden Ladies, published from 1757 to 1795, which described the physical appearance and sexual specialities of more than 120 women.

“Low-born errant drabs” were included alongside famous courtesans. The entry for a certain Miss Davenport concludes: “Her teeth are remarkably fine; she is tall, and so well proportioned (when you examine her whole naked figure, which she will permit you to do, if you perform the Cytherean Rites like an able priest) that she might be taken for a fourth Grace, or a breathing animated Venus de Medicis.”

It was the age of the coffeehouse

London in the 18th century was a city of coffee addicts. The capital’s first coffeehouse was opened by an eccentric Greek named Pasqua Roseé in 1652 and at the peak of the boom, during the Georgian period, contemporaries counted over 3,000. And they weren’t packed with silent hipsters armed with MacBooks – these were rowdy establishments where Londoners came to meet, greet, joke, debate and gossip.

Dr Matthew Green, writing for Telegraph Travel, explains: “On entering, patrons would be engulfed in smoke, steam, and sweat and assailed by cries of ‘What news have you?’ or, more formally, ‘Your servant, sir, what news from Tripoli?’ Rows of well-dressed men in periwigs would sit around rectangular wooden tables strewn with every type of media imaginable - newspapers, pamphlets, prints, manuscript newsletters, ballads, even party-political playing cards.

“Conversation was the lifeblood of coffeehouses. Listening and talking to strangers - sometimes for hours on end - was a founding principle [and] debates culminated in verdicts. In Covent Garden, the Bedford Coffeehouse had a ‘theatrical thermometer’ with temperatures ranging from ‘excellent’ to ‘execrable’. Playwrights dreaded walking into the Bedford after the opening night of their latest play to receive judgement as did politicians walking into the Westminster coffeehouses after delivering speeches to Parliament. The Hoxton Square Coffeehouse was renowned for its inquisitions of insanity, where a suspected madman would be tied up and wheeled into the coffee room. A jury of coffee drinkers would view, prod and talk to the alleged lunatic and then vote on whether to incarcerate the accused in one of the local madhouses.”

The city was exploding

For centuries London was largely contained within the old Roman walls. But in the Tudor period it expanded west, along The Strand, and east, along the road to Whitechapel. The catastrophic Great Fire of 1666 briefly halted the spread, but in the 18th century London’s urban sprawl really took off.

The wealthy went west, away from Covent Garden and towards the newly-built district of Mayfair. To the east, the port of London swelled as riches from the Empire - like rum, sugar and spices - poured in.

The Thames finally got a second bridge, in 1729, a rickety wooden one at Putney. Others followed at Westminster (1750), Blackfriars (1769) and Richmond (1777), encouraging growth to the south of the river.

Demographic statistics illustrate the changes. In 1700 around two-thirds of London’s 500,000-strong population lived outside the City. In 1800 the population was around one million, of which 85 per cent lived in the outlying areas. By 1767 the seven gates to the City and most of the old walls, which once marked London’s boundaries but now simply stood in the way, had been demolished. For details of the surviving fragments of the London Wall, follow this link.

There were heads on spikes – but not where you think

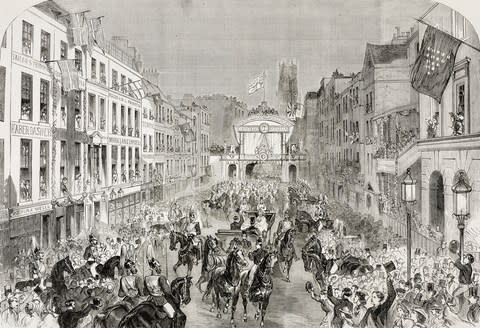

The southern gatehouse of London Bridge was notorious for displaying the severed heads of traitors, parboiled, coated in pitch and impaled on spikes. During the 18th century, however, Temple Bar, the old ceremonial entrance to the City, became the favoured location for this macabre spectacle and many a Jacobite rebel had their noggin left there as a warning to others. Enterprising Londoners even charged passing gawkers half a penny to borrow “spy glasses” for a closer look.

The spikes were finally removed in 1802 and in 1880 the Temple Bar gatehouse itself was dismantled and sent to Theobalds Park in Cheshunt. After years of neglect it returned to London in 2004 and can now be seen in Paternoster Square (minus the heads).

Gangs terrorised the streets

Hard evidence is admittedly sparse, but 18th-century London appears to have had its fair share of shady bands of ne’er-do-wells. There were the Mohocks, an alleged gang of well-born thugs who attacked men and sexually assaulted women, prompting authorities to put up a £100 bounty for information leading to their capture. According to the correspondence of Lady Wentworth, “They put an old woman into a hogshead, and rolled her down a hill; they cut off some noses, others’ hands, and several barbarous tricks, without any provocation. They are said to be young gentlemen; they never take any money from any.”

Then there were the Hawkubites, street bullies who supposedly beat up women, children and old men after dark. Other bandits from the period included the Hectors, the Scowrers, the Nickers and the Muns. Who needs Gangs of New York?

So did a monster

There were lone miscreants too, of course. Among the most curious was the so-called London Monster, active between 1788 and 1790. His alleged victims said they were followed by a man who shouted lewd obscenities and then stabbed them (never fatally) in the buttocks. As many as 50 claimed to be casualties and the incidents sparked city-wide hysteria, with band of vigilantes roaming the streets and women forced to wear homemade armour – some even stuffed copper cooking pots down their undergarments. A florist, Rhynwick Williams, was eventually convicted – despite having an alibi for some of the attacks and even though much of the evidence was contradictory (the attacker’s height varied wildly leading some to suggest there was in fact a cabal of different monsters). Williams was actually tried for damage to clothes, which - due to an old weavers’ dispute - carried a greater penalty than damage to backsides. He got six years.

It was a city of signs

With no organised system of street numbering, Londoners were encouraged to hang signs from their homes or shops to help pedestrians find their way around. Subsequently, 18th century streets were festooned with them, many several feet wide, displaying all manner of curious and hard-to-decipher symbols. A unicorn referred to an apothecary, Adam and Eve a fruit seller, and a bag of nails an ironmonger. A bugle meant a post office, a spotted cat a perfumer, and innkeepers sought to grab people’s attention with their mermaids, dragons and exotic lions. Another sign, which lives on today, was the classic red and white barber’s pole – red for blood and white for bandages. It is a legacy of the fact that, right up until the 1700s, barbers offered not just a “short back and sides” but also grisly procedures such as tooth extraction and blood-letting.

But the high street was starting to look familiar

Some of London’s oldest shops had already established themselves in Georgian London. Just like today, 18th-century Londoners could buy cheese from Paxton & Whitfield (founded in 1797), books from Hatchard’s (1797), scents from D.R. Harris & Co (1790) and Floris (1730), cigars from James J. Fox (1787), toys from Hamleys (1760), groceries from Fortnum & Mason (1707), tea from Twinings & Co (1706), wine from Berry Brothers & Rudd (1698), and hats from Lock & Co (1676).

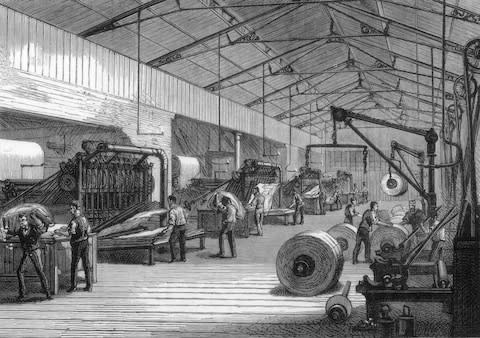

The people were mad for news

A media revolution took place in the 18th century following the relaxation of pre-publication censorship laws in 1695. Within 40 years Londoners had 31 newspapers - six dailies, 12 tri-weeklies and 13 weeklies - to choose from, and around 42 per cent of the city’s population consumed news on a daily basis.

Fleet Street was the perfect location for the burgeoning industry. Dr Matthew Green writes: “Ever since Tudor times [it] was renowned for its profusion of ale-houses and taverns and by 1700 there were 26 coffeehouses too. Because Fleet Street was one of London’s main arteries transporting people and mail between Westminster and the City, these became lightning rods for political, financial, and overseas news.

Journalists capitalised upon this and would mingle and eavesdrop in local establishments, returning to their offices with fresh gossip. Here, editors sifted through what their reporters had gathered looking for good copy for their four to six pages, each containing two columns of tightly packed news with no headlines or illustrations.

“For Fleet Street editors, the best way of building up and sustaining a loyal readership was to make their coverage as partisan as possible. Londoners dismissed ‘balanced’ papers as phoney and bland, slants needed to be bold and vivid. In spite of posthumous attempts to glorify newspapers as vessels of truth and enlightenment (the titles Sun, Star, Mirror, Guardian capture something of this), 18th-century Fleet Street was unprincipled, devious and corrupt. Plagiarism was rife, taking bribes from ministers was common and early hacks like Daniel Defoe sold their pen to the highest bidder.”

There were fairs on the Thames

There were vineyards in London thanks to the Medieval Warm Period, but hot on its heels was the Little Ice Age. Average temperatures dropped across much of Europe during the Georgian era, which, combined with the fact that the unembanked Thames was wider and slower, saw London’s main river freeze over on a regular basis. On at least five occasions (1683-4, 1716, 1739-40, 1789 and 1814) the ice was thick enough for Londoners to celebrate with a “Frost Fair”. An eyewitness account of one such shindig reads: “The Thames was so frozen that a great street from the Temple to Southwark was built with shops, and all manner of things sold. Hackney coaches plied there as in the streets. There were also bull-baiting, and a great many shows and tricks to be seen.” Another from 1789 boasted fairground booths, puppet shows and roundabouts. In 1814 an elephant was led across the river below Blackfriars Bridge and a pop-up pub, called the City of Moscow, served booze to revellers.

The fairs lasted hours, days or weeks, depending on the weather, and rapid thaws often ended with a mad scramble for dry land and loss of life.

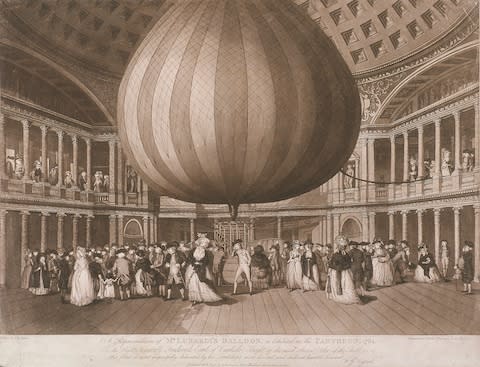

We had an answer to the Pantheon

One of London’s greatest lost buildings, opened in 1772, was named The Pantheon for its spectacular neoclassical dome that bore a passing resemblance to the Roman original. Envisaged as a venue for the winter “season”, when cold weather put Ranelagh Gardens off the menu, it occupied a large plot on the south side of Oxford Street. The opening night, January 27, saw 1,700 members of high society pay up to £50 each for tickets (the equivalent of more than £7,000 today). Handel performed there in 1784 and soon after the Italian aeronaut Vincenzo Lunardi showcased his giant hydrogen balloon inside the vast building.

It was briefly converted into an opera house before a large fire struck in 1792. The rebuilt venue was a failure, and in 1833 it was turned into an indoor market, before the wine merchants W. and A. Gilbey bought the property in 1867 to use as an office and showroom. It was finally demolished in 1937 and a branch of M&S now occupies the site.

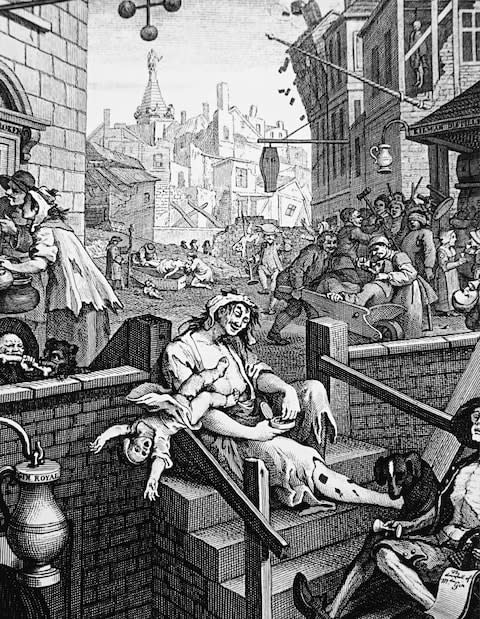

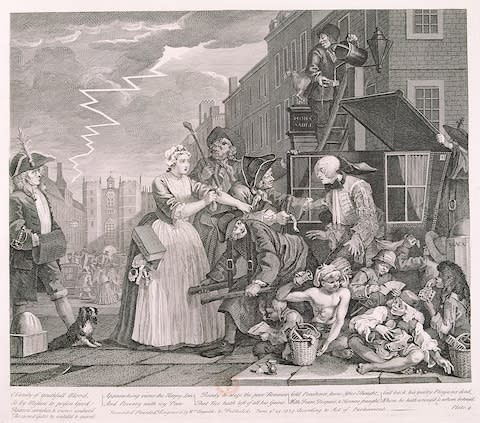

Everyone was soused on gin

English soldiers discovered gin fighting alongside Dutch troops in the Thirty Years’ War (their habit of downing vast quantities before going into battle may well have given us the idiom “Dutch courage”) and by the 1730s, encouraged by the Government to embrace the industry of distilling, Londoners had caught on too. As many as 1,500 distilleries were flooding the streets with cheap spirits, often mixed with turpentine, sparking public drunkenness on a scale never seen before or since. Pubs, until then only familiar with beer, served gin by the pint, and one establishment at the time advertised it wares thusly: “Drunk for a penny / Dead drunk for twopence / Clean straw for nothing.”

“In 1741 a group of Londoners offered a farm labourer a shilling for each pint of gin he could sink,” writes Mark Forsyth, author of A Short History of Drunkenness. “He managed three, and then dropped down dead.”

He adds: “The most notorious single incident of the gin craze was the case of Judith Defour, a young woman with a daughter and no obvious husband. The daughter, Mary, had been taken into care by the parish workhouse and provided with a nice new set of clothes. One Sunday, in January 1734, Judith Defour came to take Mary out for the day and didn’t return her. Instead, she strangled her own child and sold the new clothes to buy gin.”

Efforts to crack down on the craze bore little fruit. A blanket ban sparked full-blown riots and a tax hike simply drove distillers underground (while suspected informants were beaten to death).

While we drink rather more responsibly these days, the spirit has experienced something of a renaissance in recent years with specialist gin bars popping up across the capital.

Sedan chairs clogged the streets

Long before black cabs and Uber there was the sedan chair, a small cabin with a seat and a detachable roof mounted on two poles and carried by a pair of stout footmen. A common sight in London from the middle of the 17th century, they were used by wealthier citizens to avoid the crowds and muddy streets. And they moved faster than you’d think. Bearers would run at high speeds, ordering startled pedestrians out of the way (“By your leave, sir!”), a practice that resulted in frequent accidents. Just like today’s cabbies, chairmen were licensed and waited for business in sedan stations – or else servants were sent out to fetch one by shouting “Chair! Chair!”

People wore patches

Beauty patches, or “mouches”, were tiny pieces of black velvet, silk or thin leather that were attached to the face to cover blemishes, smallpox scars – or simply as decoration. They depicted stars, diamonds, suns, trees and doves, with the shape of the patch, and its position on the face, sometimes holding a hidden message.

Ladies, according to handbooks from the time, would wear a patch near the lip as a form of flirtation, a heart-shaped patch on the left cheek to show they were engaged, or one on the opposite cheek if they were married. Political allegiances could be advertised too: Tories wore one on the right-hand side of the face, Whigs on the left.

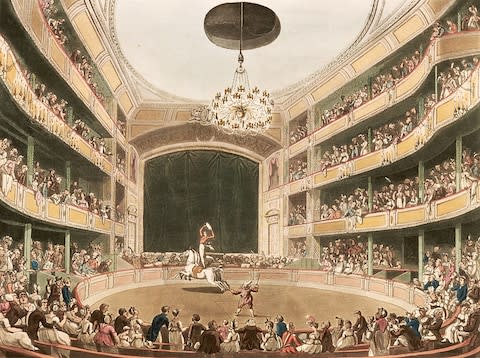

There was the world’s first circus

Astley’s Amphitheatre opened in 1773 on the Westminster Bridge Road in Lambeth. It evolved from a riding school and was initially an equestrian affair. One of Philip Astley’s acts involved the novel combination of riding and a comedy routine, while his wife Patty wowed the crowds by circling the ring with a swarm of bees covering her arms. The couple were soon joined by acts from the pleasure gardens of London and the streets of Paris, however, including acrobats, jugglers, clowns and strong men. It was considered the first modern circus and many continue to use the same ring dimensions as Astley’s original.

The rich gorged on chocolate

Coffee wasn’t the only hot drink to conquer London in the 18th century. Chocolate, served warm, sweet, and mixed with cinnamon, was considered - like tobacco - a miracle cure for all manner of ills. It was expensive, however, so only available to the upper classes, who flocked to a cluster of self-styled “chocolate houses” around St James’s Square to indulge in both cocoa and reckless gambling.

“The inner gaming room at White’s chocolate house, is depicted in the sixth episode of Hogarth’s Rake’s Progress in all its debauched glory (fittingly, it is also on fire, though few customers seem to notice or care),” writes Dr Matthew Green. “It is a picture of greed and despair; the posture of the ruined rake, hands held high as though for divine intercession.

“The legendary White’s betting book, an archive of wagers placed between 1743 to 1878, by which point the chocolate house had evolved into a club, lends credence to Hogarth’s attacks. Much of the time, it reads like a litany of morbid and bizarre predictions: ‘Mr Howard bets Colonel Cooke six guineas that six members of White’s Club die between this day of July 1818 and this day of 1819’, reads one typical entry (Colonel Cooke won). Elsewhere there are bets on which celebrities will outlive others; the length of pregnancies; the outcomes of battles; the madness of George III; the future price of stock; and whether a politician will turn up to the Commons in a red gown or not.

“To place the modern-day equivalent of £180,000 on the roll of a single die, as happened at the Cocoa Tree in 1780, may strike us as downright nihilistic today but for the Georgian nobility it was a brilliant way of projecting their status, giving every meaning to their frequently idle, chocolate-guzzling existence.”