I realized the magic of lesbian women like me thanks to this 1970s photographer

For Women’s History Month, we are publishing Celebrate Her—an essay series honoring women who deserve more public praise for how they have inspired us individually and empowered their communities: Scientists, activists, and artists. Screenwriters, comedians, and actors. Burlesque dancers and wrestlers. Those who have passed on and those who are still with us. Here, HG contributor Hannah Brashers celebrates 1970s photographer Donna Gottschalk for her soft, magical, non-sexualized documentation of lesbian women. Read the rest of these essays here throughout March, and read about even more incredible humans in our Women Who Made Herstory series.

Lesbian art makes me cry. Last June, as I watched Todd Haynes’s 2015 film Carol for what was probably the 48th time, I found myself sobbing into my blankets. It wasn’t the plot of the movie that made me emotional—it was the beauty of the love between two women. I decided that night that I would come out to my family.

I’ll admit the second time I cried that hard over lesbian content, I was tipsy on a $2.98 bottle of Aldi wine. The newest catalyst for my tears was the music video for “Lost On You” by lesbian singer LP. While the lyrics are heartbreaking, seeing two openly gay women interacting so intensely is what did it for me. I was drunkenly curled up in a ball on my living room floor as my best friend stroked my hair, wailing, “How can people hate us? Lesbians are so beautiful!”

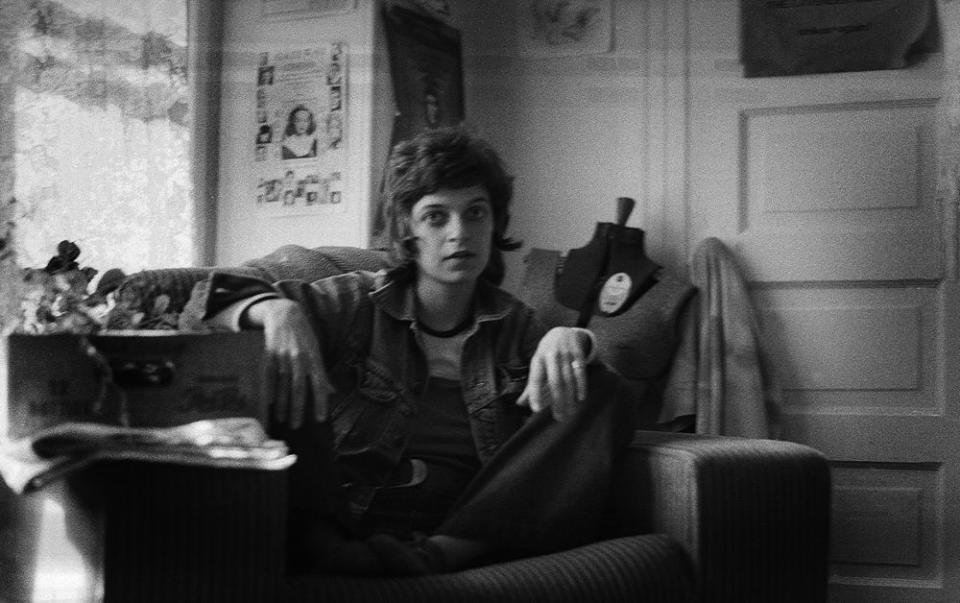

Just like Carol and LP make me cry, the first time I saw Donna Gottschalk’s photos, I was instantly moved to tears. I first stumbled upon Gottschalk when one of my favorite professors sent me an email with a link to the photographer’s work. Her black and white photos of 1970s lesbians provided a tangible reality for what I’d always intellectually known to be true, but perhaps had never believed—we’ve always existed.

It’s no secret that society hypersexualizes and fetishizes lesbians. Gottschalk’s photos provided an alternate narrative.

Her photographs show lesbian women as so much more than the butt of jokes about scissoring and U-Hauls. Many of Gottschalk’s photos are of nude women, and many capture women together in intimate situations that aren’t sexualized. Instead, they depict a connection that goes far beyond sex, a connection that is emotional and intellectual for two women bound by the common experience of womanhood. This illustration of women loving women—a reality captured in Carol, LP’s music, and Gottschalk’s photos—is what triggers a visceral reaction for me. Lesbians so infrequently receive representation that is this magical.

Donna Gottschalk, 69, was born and raised in a tiny apartment on New York’s Lower East Side. As a young art student, Gottschalk began taking photos of her working class family and the radical lesbian communities of the 1960s and 1970s. Although she’s been taking photos since she was 17 years old, Gottschalk has never identified as a photojournalist. She worked odd jobs for most of her life—from topless bartender to horse drawn carriage driver. For a period, Gottschalk was the operator and owner of a photo lab in Connecticut, and she now resides on a small farm in Victory, Vermont.

For the past 50 years, Gottschalk’s photographs have been locked away in her personal archives. Only in August of 2018 did the world get to see her moving collection. Since then, her photos have been on exhibition in “Brave Beautiful Outlaws” at New York’s Leslie-Lohman Museum. Looking through her photographs, it is hard to believe that art this wondrous has been hidden away for decades.

Gottschalk’s art was never created with the intention of sharing with the public, she tells The New York Times. Instead, her photos are personal, intimate, taken in bedrooms and yards. She took the photos to remember these interactions and would tell her subjects, “If I get to be old, I want to remember you. I want to remember you just the way you are now.”

Some of the photos also capture the dreamy spirit of Gottschalk’s transgender sister Myla before she transitioned. Gottschalk has also forever memorialized the powerful beauty of her lifelong friend Marlene. Marlene’s strength is viscerally communicated through the determined slant of her jaw as she poses with a beer in the back of a truck or with a quiet smile as she poses with her arms crossed in front of her chest. The photographs capture the women behind 1970s lesbian activism, but instead of photographing them combative and angry in the streets, she captured softness, love, and startling vulnerability.

Many of the people in Gottschalk’s photographs did not survive as they faced the challenges of poverty, addiction, AIDS, and queerphobic violence. Marlene, who was a sexual assault survivor and former foster child, struggled with mental illness and eventually died of cancer while living out of her van.

“These people were all very dear to me,” Donna Gottschalk said in an interview with The New York Times. “And they were beautiful. These pictures are the only memorial some of these people will ever have.”

My favorite photograph of Gottschalk herself is one taken by the formidable lesbian photojournalist Diana Davies. Taken at the 1970 Christopher Street Gay Liberation Day parade, a young Gottschalk holds a sign that reads, “I am your worst fear/ I am your best fantasy.” Her chin is uplifted as she looks down her nose at the camera and both of her feet are planted firmly in the ground. It’s a stance that is unflinching and unafraid.

A post shared by Saskia Scheffer (@saskiany) on Sep 30, 2018 at 5:57am PDT

Like the Davies’s photograph, Gottschalk’s art depicts the strength and persistence of queerness.

Gottschalk’s art will persevere for decades to come—unabashedly queer in the face of it all. This bravery is what is most stunning to me. As a lesbian existing in the Trump era, Donna Gottschalk’s art is a reminder that survival is possible and that loving women is timelessly beautiful.