The real reason diets fail, by a leading bariatric surgeon

Mr Johnson weighed around 150kg (23 and a half stone). He had always been on the big side but just could not lose weight, even when he carried out the instructions of numerous dieticians, nutritionists and fitness instructors. He had recently developed diabetes and had sought a referral to my bariatric surgery unit at University College London Hospital.

His semi-naked body was now being prepared for surgery. Every muscle had been paralysed by an injection of curare and he was connected to a breathing machine via a throat tube. Wint, our anaesthetist, had administered a form of hypnotic so that all memory of this event would be erased. She had topped him up with a shot of morphine.

He was lying flat on the operating table, arms outstretched and legs apart, as if mid-star jump. I was reminded of Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man sketch, but with a very large modern-day individual.

I stood between Mr Johnson’s legs, then sliced a 12mm cut through his skin with a blade and placed a thin surgical telescope (an instrument relaying the images of the surgery, via a digital camera, to the TV monitor) into a plastic tube and aimed it in Mr Johnson’s abdomen, so that each layer of his abdominal wall – fat-fascia-muscle-fat – was visible on the screen as I carefully pushed the tube into his abdomen.

The sleeve gastrectomy procedure I was about to perform would be life-changing. A year from this day, after I surgically removed 70 per cent of his stomach, he would weigh around 90kg (just over 14 stone), his diabetes would have disappeared, he would not crave bad food, and his quality of life would be immeasurably improved.

We had an audience that day – two young medical students watching the process. I wanted to make sure they learned from their experience, and started by pointing the camera at Mr Johnson’s engorged liver. “Twenty per cent of obese people have this type of liver. It’s due to too much fat and sugar storage and can cause inflammation, and liver cirrhosis in the future.”

I swung the camera to point out the omentum – the inflamed yellow fat hanging like an apron from the large bowel – as well his vast pink stomach, indicating the part that was going to be removed. “The stomach will be reduced in capacity from the size of a Galia melon to the size of a banana, going from a 2-litre capacity to around 200 to 300cc… but the question I want to ask you is why is this man having this surgery? Why can’t he just go on a diet?”

“Maybe he tried but lacked the willpower,” one replied. “Could it be that he has a food addiction?” the other answered.

“Haven’t they taught you anything about leptin in medical school yet?” I enquired. After a long pause, one student replied, “Oh yes, we had a lecture, which mentioned it. I think it comes from fat cells and influences appetite, but that’s all we were told.”

I silently shook my head – medical schools were still not explaining obesity to students.

I started to dissect the outer edge of Mr Johnson’s stomach away from its fat and blood vessels using an instrument called a harmonic coagulator. “Leptin is the master controller of our weight, and when it stops working properly people lose control of their weight.

“It’s a hormone that comes from fat, and the more fat someone has, the higher the leptin level in the blood. [So] this man will have a lot of leptin in his system.” I grasped Mr Johnson’s abdominal belly fat between my finger and thumb to demonstrate. “Leptin acts as a signal to the hypothalamus, the part of the brain that controls how hungry or full we feel…

“When things are working normally, your hypothalamus will be able to sense if you have put some weight on. It will sense the increase in the leptin level in the blood and will respond by increasing feelings of fullness, and decrease your appetite. The response is that you naturally eat less… until your leptin level returns to normal.

“So, what has happened to this signal in Mr Johnson? His leptin level would be very high if we measured it.” I looked up. The students seemed to be stumped by this question… then one suggested that the leptin signal might somehow be being blocked.

“Yes! Mr Johnson has a condition called leptin resistance. He has lots of leptin in his blood but it is not being seen by his brain. It’s being hidden. And the culprit is the hormone insulin. Leptin and insulin have a common signalling pathway within the hypothalamus. If insulin levels are high, then the insulin will block the receptor that leptin is supposed to activate.

“Mr Johnson has a typical Western diet that includes lots of sugar and refined carbohydrates. In addition, he will be much more likely to snack between meals. This leads to lots of insulin being produced, and that blocks the leptin signal from getting through.”

I pointed to the TV monitor, and focused on the gleaming fat hanging off Mr Johnson’s stomach. “You see this fat looks abnormal – it’s too moist, it’s inflamed, and the inflammation is caused by his obesity. All this fatty inflammation sends a chemical called TNF-alpha into the blood, which causes inflammation directly to the hypothalamus in the brain, again blocking the leptin signal.”

I had finished the dissection; the stomach was now mobilised enough for its division to begin. “Most people suffering with obesity are getting signals to eat more. Their appetite is high all the time. It’s embarrassing for them to eat too much in public, so often they binge-eat in private.

“Mr Johnson weighs over 23 stone, has an unhealthy appetite and is tired all the time,” I said to the students. “Our conventional understanding of obesity would point to his supposed greed and laziness as being character flaws. This is the problem with obesity – people blame those things for causing it but it is a condition that causes this behaviour. These are its symptoms, not its cause. Just like the symptoms of a cold might be a cough and a fever.”

It was time to staple Mr Johnson’s stomach into two – the small tube-like new stomach that would remain, and the bulk of the old stomach that was to be removed. Without its blood supply, this part was already turning blue.

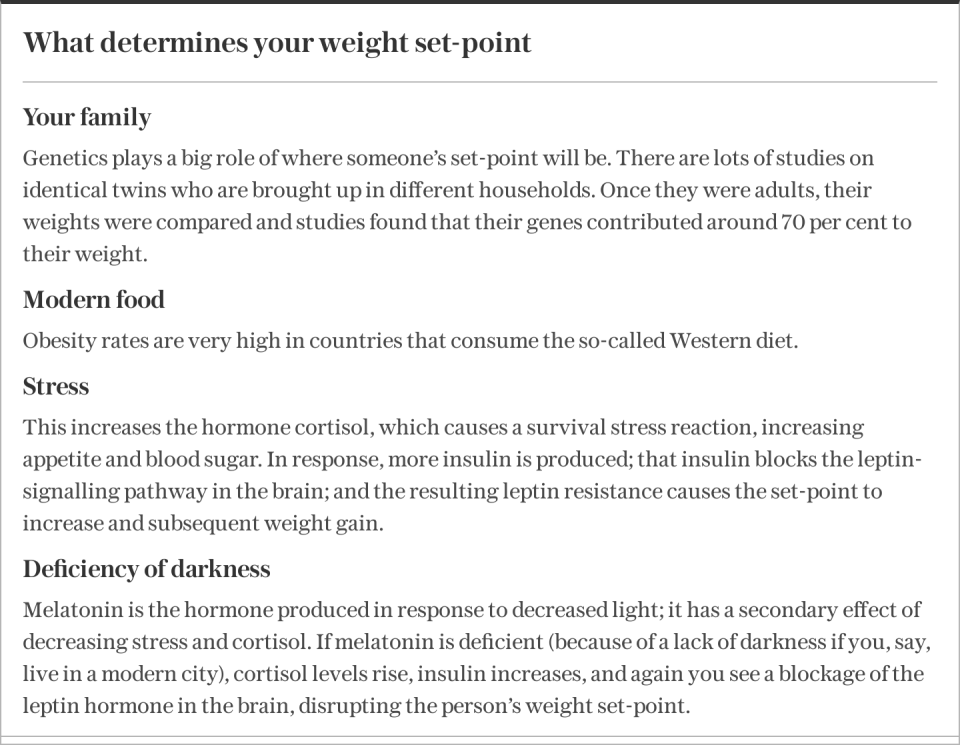

I continued: “The problem with Mr Johnson and all people who suffer with obesity is that the weight that they are, is what their brain thinks is a healthy weight. This is called their weight set-point.”

The problem comes, I explained, if your weight set-point is in the overweight or obese category. “If this happens, then every effort to force your weight down by simple calorie restriction and exercise will ultimately fail.”

The operation was finished. Faisal, my assistant surgeon, closed the skin and I had my students’ attention again. “I mentioned that tug of war that goes on when someone tries to lose weight by dieting… But when you speak to patients in the clinic, they commonly say that not only do they put all their lost weight back on, but they end up being heavier than before.

“This happens because the brain senses that the environment has become hostile. It senses the calorie restriction that occurred due to the diet and has calculated that this might happen again. So, low-calorie dieting is counterproductive as far as weight loss is concerned.”

“What’s the best way for someone to lose weight if low-calorie dieting doesn’t work?” Wint asked.

I told them to imagine that a person’s weight set-point is a ship’s anchor. “The ship can try to sail away from the anchor, but it’s always eventually stopped… This is what happens if you try to diet and exercise your way to a new weight. The more effort you put in, the more forcefully you will eventually be pulled back.”

“But,” I continued, “if you understand how the brain calculates where it wants your body’s weight to be – its weight set-point – then you don’t have to fight against the anchor by forcibly sailing away from it, ie, dieting and exercise.”

One way the weight anchor can be moved is through dietary choices. “Rather than cutting calories, if you change the types of food you eat away from those that block the leptin signal, you will shift the position of your set-point anchor. We know that stopping sugar or going on an ultra-low-carb diet means people no longer need to produce so much insulin.”

“So, if all our patients gave up sugar and went low-carb, would they no longer need bariatric surgery?” Wint was playing devil’s advocate. Asking the difficult questions for our students’ benefit.

“That’s a very good point. They would certainly lose some weight. But because they are usually very obese, they also have a great deal of inflammation, which can block leptin signalling, so there will still be leptin resistance present even after lifestyle changes. Also, we have to consider the addictive nature of foods once someone has struggled with obesity for many years…

“So, yes, in answer to your question, if someone obese cleans up their eating behaviour they will lose some weight, but they will still have a degree of leptin resistance caused by the inflammation, and this will signal for them to continue eating. Combine these strong hormonal appetite signals with deeply ingrained reward pathways, habits and food addictions, and it’s going to be very difficult to continue only eating healthy foods.”

What most obese people tell me is that their problems really started when they began their first diet. They may have only been in the overweight category, but it led to that weight-loss tug of war and eventually becoming heavier than before the diet. Because most doctors, dieticians and nutritionists don’t fully understand obesity, they will still advise calorie restriction to lose weight.

I was concluding the teaching session now. Our students were nodding enthusiastically. I hoped that their newfound knowledge of obesity would make them more compassionate when treating people struggling with it in their future careers.

I turned to Wint, who was waking Mr Johnson up. He had now been transferred to his extra-large hospital bed and was coughing out his breathing tube.

“Operation is over, Mr Johnson, everything went OK, just relax.” It was time for coffee.

Abridged extract from How to Eat (and Still Lose Weight): A Science-Backed Guide to Nutrition and Health, Andrew Jenkinson (Penguin Life); pre-order a copy at books.telegraph.co.uk You can read the first extract here