The Price of Using Social Media in Saudi Arabia

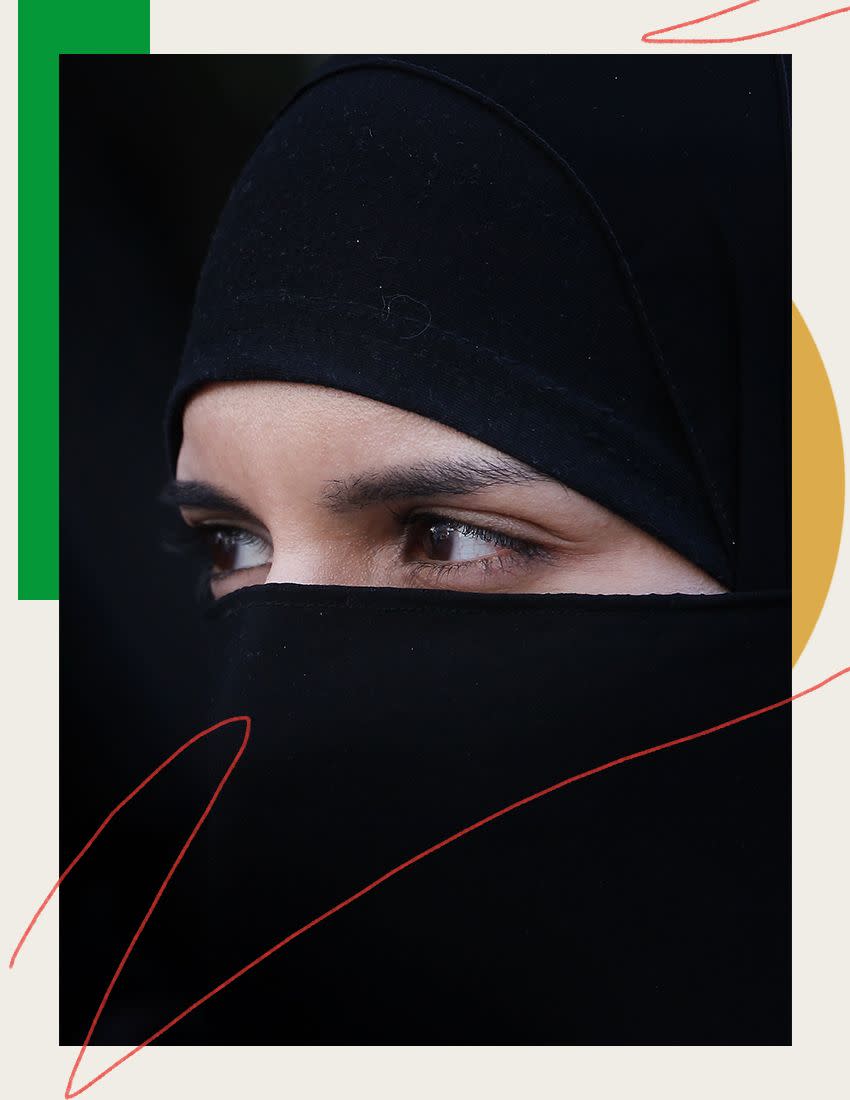

In Saudi Arabia, a woman being active on social media is seen by some families as breaching the so-called “honor code,” which demands female family members be morally pure and modest, or risk tarnishing the family name. In some families, simply posting a profile picture on social media is considered immoral.

A few years ago, a woman went missing from the apartment she shared with her family near the capital of Riyadh. Her younger sister had returned home that evening to find the apartment empty. This wasn’t unusual—her older sister was often out socializing or shopping when the coolness of the evening wafted in to soothe the sweltering city. It was only when she saw that her sister’s purse and abaya were still in her room that she knew something was wrong. She called her parents, who alerted the local police.

Days later, her older sister still missing, the young woman turned to social media hoping the public would be able to help find her. On Twitter, she alleged that her brothers may have been responsible for murdering her sister. They were conservative, she claimed, and had recently become aware of her sister's public Snapchat account which showed photographs of her face and hair exposed under a loose fitting headscarf.

The next day, her sister’s body was found in the desert outside the city.

The older sister had gone for a job interview the day before she disappeared. “It was her first job interview and she was so excited about it and had been preparing for weeks,” a friend of hers told me. “She said once that all she wanted to do was to be able to take care of her younger siblings.” She describes the woman as talented and life-loving, someone “had big dreams to be famous and ideas of what she could do with her future.”

“But mostly,” she adds, “she wanted the freedom to work.”

Millions of Saudi women remain powerless under the tight grip of country’s defacto ruler, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman Al Saud (known as MBS), despite the country being classified as “the global top reformer for women's rights” in 2020 by the World Bank. Though Saudi Arabia has made headlines for its reforms, including allowing women to get a passport and travel without the approval of a male relative, critics say such measures are superficial. In March 2022, Saudi Arabia passed its first Personal Status Law, further codifying aspects of male guardianship; women still need permission from male relatives to marry, to leave prison, and to obtain certain sexual and reproductive healthcare. While women no longer officially need permission from male guardians to work, in practice, some employers still require it. And although there is nothing official that says Saudi women need a male guardian’s permission to leave the house, if they do so against their male guardian’s wishes, the guardian can file a claim of disobedience against them which have previously resulted in arrest, forcible return to their male guardian’s home, or imprisonment in secret detention centers.

Those who take high risks in fleeing the country can still be forcibly returned by male family members, sometimes with the help of Saudi authorities, according to Rothna Begum, senior women’s rights researcher at Human Rights Watch. Begum points to the case of Dina Ali Lasoom, a Saudi woman who was filmed by a passenger in 2017 on a flight from the Philippines to Saudi Arabia her arms and legs bound, her mouth gagged with tape as she was forced by male relatives kicking and screaming onto the plane. Dina has not been heard of since. Begum says that Dina’s uncles worked for the interior ministry and that the Saudi embassy was also involved in having her forcibly returned. “The male guardianship system continues to render women perpetual minors, and facilitates abuse against them,” Begum adds.

Many female Saudi human rights campaigners have been detained for speaking out against such policies and remain in prison; some report being subjected to abuse including electric shocks, flogging, sexual assault, and water-boarding. One of those who reported abuse was Loujain al-Hathloul, a prominent activist who doggedly campaigned for years for women’s right to drive and against the country’s male guardianship system, only to be detained in 2018 on terrorism charges—even after the country allowed women over age 21 to drive. “Voicing your rights is not only labeled as rebellion. It is now considered terrorism,” Loujain’s sister Lina al-Hathloul told me. Loujain was released in February 2021, but is subject to a five-year travel ban, and a suspended sentence of nearly three years (meaning authorities can return her to prison at any time if she resumes her activism). The Saudi government has previously denied allegations of torture, saying it does not "condone, promote, or allow the use of torture."

MBS’ control extends to social media, where the government has waged a campaign against virtually all forms of activism and dissent. This crackdown began, in part, on Twitter, which is used by approximately 10 million people in Saudi Arabia. More than 40 percent of all active Twitter users in the Arab region are in Saudi Arabia, making it the platform’s largest Middle Eastern market.

In January of 2021, British resident and Leeds University PhD student and mother of two Salma al-Shehab was arrested while on holiday in the Kingdom for retweeting Twitter accounts that supported women's rights. She was charged with using the internet to “cause public unrest and destabilize civil and national security” and, in August 2022, was sentenced to 34 years in prison followed by a 34-year travel ban. Amnesty International said that authorities intend to use her to set an example amid their unrelenting crackdown on free speech.

The same day that al-Shehab was sentenced, another Saudi woman, Nourah bint Saeed Al-Qahtani, was sentenced to 45-years in prison after using Twitter to peacefully express her views. Al-Qahtani was accused of “using the internet to tear Saudi Arabia’s social fabric” and for using social media to “violate the public order.” Little is known about the circumstances around her arrest and conviction other than that she criticized Saudi rulers.

A year later, in January 2022, prosecutors pushed for the death penalty against 65-year-old Awad Al-Qarni, a prominent pro-reform law-professor in Saudi Arabia, for alleged crimes including having a Twitter account and using WhatsApp to share news considered “hostile” to the kingdom, according to court documents. The court has yet to make a formal judgment in the case.

And there may be countless others. Bethany Alhaidari, the Saudi Officer at the Freedom Initiative, a Washington D.C.-based human rights non-profit which works to free political prisoners in the Middle East, says her organization has received reports of hundreds of young women who were detained over social media posts. “Some have been sentenced to jail by courts already,” she adds.

The younger sister took an extraordinary risk tweeting about her older sister’s disappearance. But she wasn’t afraid, her friend says, “she wanted justice for her sister, even if it cost her life.” In addition to accusing her brothers, she called for justice for her sister and even posted photos of the crime scene. Then, the police visited the family’s home and told her not to publicize her claims. Under pressure, she deleted the tweets, telling her friend that she feared for her safety.

But she may have created a movement she could not control. Many Twitter users were concerned that the young woman was now facing similar danger after publicly sharing details about the case. Users created hashtags in support of the sisters and slammed MBS for not taking action against honor killings.

Amid the online outrage over the incident, Saudi Arabian authorities released a statement saying that two citizens in their 30s had been arrested on suspicion of their involvement in the incident that caused the woman’s disappearance and death. According to the sister, those two citizens were her brothers.

At first, it felt like a victory, but then, the sister was also arrested—for “obstructing the investigation.” She was not formally charged, but her phone was taken by police and officers threatened that her bank account would be frozen and her access to other government services barred if she did not sign a pledge saying that she would stop speaking about her sister's death. She signed it.

“This is the state of women’s rights in Saudi today,” her friend says. “And we’re talking about incidents that actually reach social media—think about all the other unreported incidents hidden behind gated compounds. Under MBS, everything is monitored. Our social media accounts are being suspended and our voices are being silenced for talking about anything from foreign policy to women's rights and religious reforms, where can we turn? Freedom for women and freedom of speech is not dying in Saudi Arabia, it’s dead already.”

After the younger sister was released, she tweeted again—this time saying that she was leaving the investigation to the authorities. Several social media users noted a change in her tone, prompting concerns that she was being silenced or coerced. But their bigger fear was that she would disappear altogether.

Since the older sister’s death, other disappearances across the Kingdom have followed. On February 17, 2021, Refa Al-Yemi, a 40-year old, single mother of four children, went missing from her home in Jeddah. #Where's _ Rafa _ Al Yami started circulating on Twitter. On May 8, 2021, Ayesha Mohammed, a women’s rights activist, shared a video detailing the death of Hadil al-Harthi, a young Saudi woman who was found dead; users on Twitter speculated she may have been killed for sharing photos of her face on her TikTok account. Along with the tragic stories, users post hashtags including #TheSaudiWomanIsAfraid.

In July 2021, Saudi Arabia’s Social Service Department at the Ministry of Health revealed that they were investigating 2,726 cases of domestic violence, including 2,035 against women. Yet reports continued to emerge on social media of women going missing or being killed by family members in honor killings. In April 2022, an English newspaper in Saudi Arabia reported that a Saudi woman had been killed by her husband in an acid attack in Jeddah. Her daughter had also been seriously burned in the attack. The man was arrested by the police.

Months after her older sister’s funeral, the younger sister turned to social media again, saying that her brothers had been released and returned home. She asked the public to keep pressure on the case if she is arrested again or imprisoned. The tweet has since been deleted and her account has been deactivated.

Years later, her friend still fears for what may happen to the younger sister. “I call her daily,” the friend says, “not even to ask if she is fine, just to check that she is alive and hasn’t been taken away. What else can I do?”

You Might Also Like