When Petula Clark touched Harry Belafonte – and caused a scandal

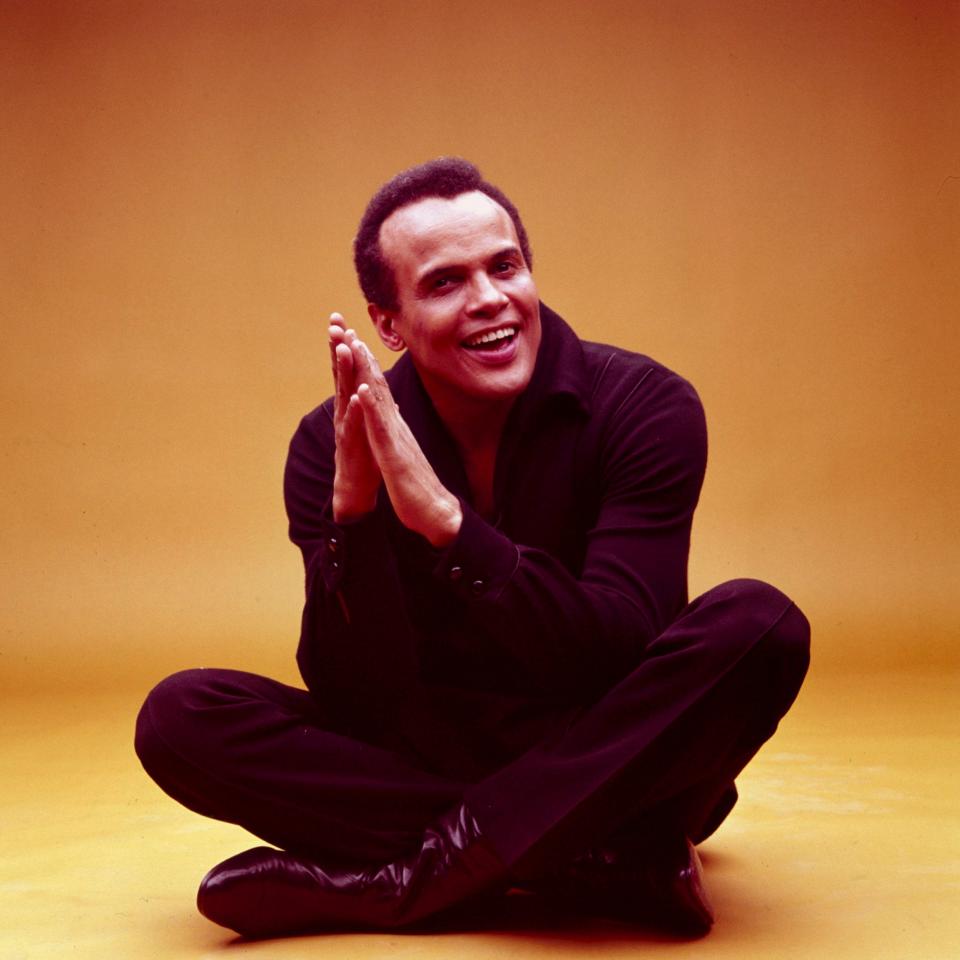

The singer and actor Harry Belafonte, who has died at the age of 96, led a courageous and trailblazing life in which he boldly stood up for humanitarian causes of all kinds, from being a leading voice in the Civil Rights movement of the Fifties and Sixties alongside Martin Luther King to condemning everything from apartheid to the policies of the George W Bush administration.

This dedication to liberal politics extended into his work as a musician and on screen, whether it was in the role-reversal drama White Man’s Burden, in which he starred opposite John Travolta in a story about an alternative America where the social and economic statuses of white and black citizens have been reversed, or his final on-screen appearance in Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman, in which Belafonte, now suffering from ill health, was appropriately cast as Jerome Turner, a civil rights pioneer who has a show-stopping monologue about a lynching taking place in 1916 in Waco, Texas.

Belafonte, along with his lifelong friend Sidney Poitier (who he referred to, upon Poitier’s death, as his “brother and partner in trying to make this world a little better”) was one of the most visible black celebrities from his first rise to fame in the Fifties, and beyond.

Yet while Poitier went out of his way to offer the predominantly white citizens of middle America reassurance that he was an uncontroversial and unthreatening figure, Belafonte was a less mollifying presence; one who followed in the footsteps of his idol Paul Robeson by refusing to compromise his principles and ideals, however much trouble it led to.

Belafonte's success as the so-called “King of Calypso” was matched with an unyielding dedication to the Civil Rights movement, which saw him – like Robeson – refuse to perform in the segregated concert halls and theatres of the southern States, and also to make public statements in support of Martin Luther King, for which courageous and steadfast actions he was blacklisted in the McCarthy era. Belafonte was fortunate in that the hugely influential broadcaster Ed Sullivan (who also gave the Beatles their big break in America) chose to ignore the blacklist and invited the singer onto his show anyway. The resulting exposure meant that Belafonte became one of the most famous and popular singers in America.

It is a telling difference between Poitier and Belafonte that, while both men made films dealing with the then-taboo subject of interracial romance, they went about it in entirely different ways. Poitier appeared in the now-dated but then-trailblazing picture Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner in 1967, in which any potential for controversy was diluted by the Poitier character – a doctor, no less – being portrayed as nothing less than a secular saint.

A decade before, however, Belafonte had appeared in the less artistically respectable drama Island in the Sun (based on a bestselling novel by Evelyn Waugh’s elder brother, Alec) as David Boyeur, an ambitious local politician on a West Indian island who captures the heart of a member of the white elite.

Although the film ends with Boyeur spurning his would-be lover’s advances, its depiction of their flirtation was still considered highly controversial. Joan Fontaine, who played the aristocratic woman, was sent death threats by the Ku Klux Klan, and the film was banned in Memphis, Tennessee for being “too frank a depiction of miscegenation, offensive to moral standards, and no good for either white or Negro.”

Belafonte – unlike the more cautious and conservative Poitier – relished both the controversy and the chance to stand against the small-minded and bigoted forces of oppression. In an example of art imitating life, the actor would have an affair with Joan Collins on the film’s set. She later recalled: “He was mesmerising, and we soon began an affair, away from prying eyes, in my tiny apartment. But, after a few exciting liaisons, we knew we had to cool it. He went back to his wife and I moved on.”

Yet this controversy would seem mild compared to what came at the end of the Sixties, by which time Belafonte was as famous for his political views as he was for his singing and acting. He had turned down several film roles (most notably in Otto Preminger’s film of Porgy and Bess) because he believed that they contributed to racial stereotyping. Poitier took on the role of Porgy, but the film’s indifferent reviews bore out Belafonte’s reluctance to play the part.

Instead, he continued his musical career. But his outspoken opposition to everything from the Vietnam War to racially-inflected poverty meant that he was regarded by jittery TV executives as unreliable. He may have stood in for the legendary Johnny Carson as host of the Tonight Show, but he was a polarising, endlessly controversial figure, especially when it came to network television’s all important advertisers, who were not known for their open-minded or liberal attitudes.

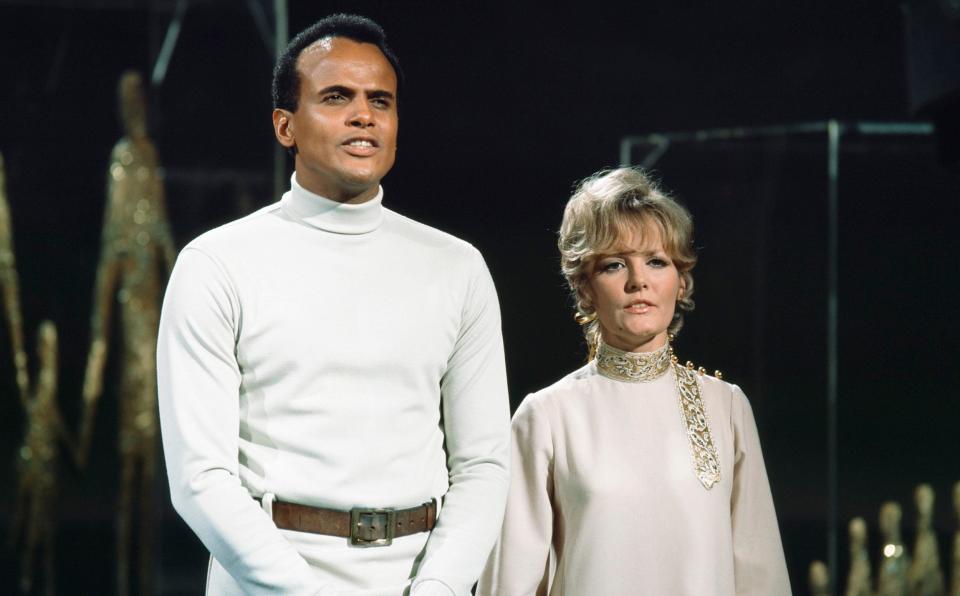

Belafonte was hired to appear on an NBC show in 1968 that was designed to showcase the British singer Petula Clark to American audiences. Clark had had a success with her single Downtown in 1965 – topping the US charts and winning a Grammy in the process – and was now famous enough to merit her own hour-long variety show.

Belafonte, meanwhile, was asked to do a 10-minute solo performance during Clark’s appearance, before the two singers would duet on Clark’s anti-war song On the Path of Glory – the sentiments of which were especially dear to Belafonte. Yet there had been disquiet about his appearing on the show at all, as the show’s sponsor Plymouth Motors’ head of advertising Doyle Lott had attempted to get Belafonte barred, albeit unsuccessfully.

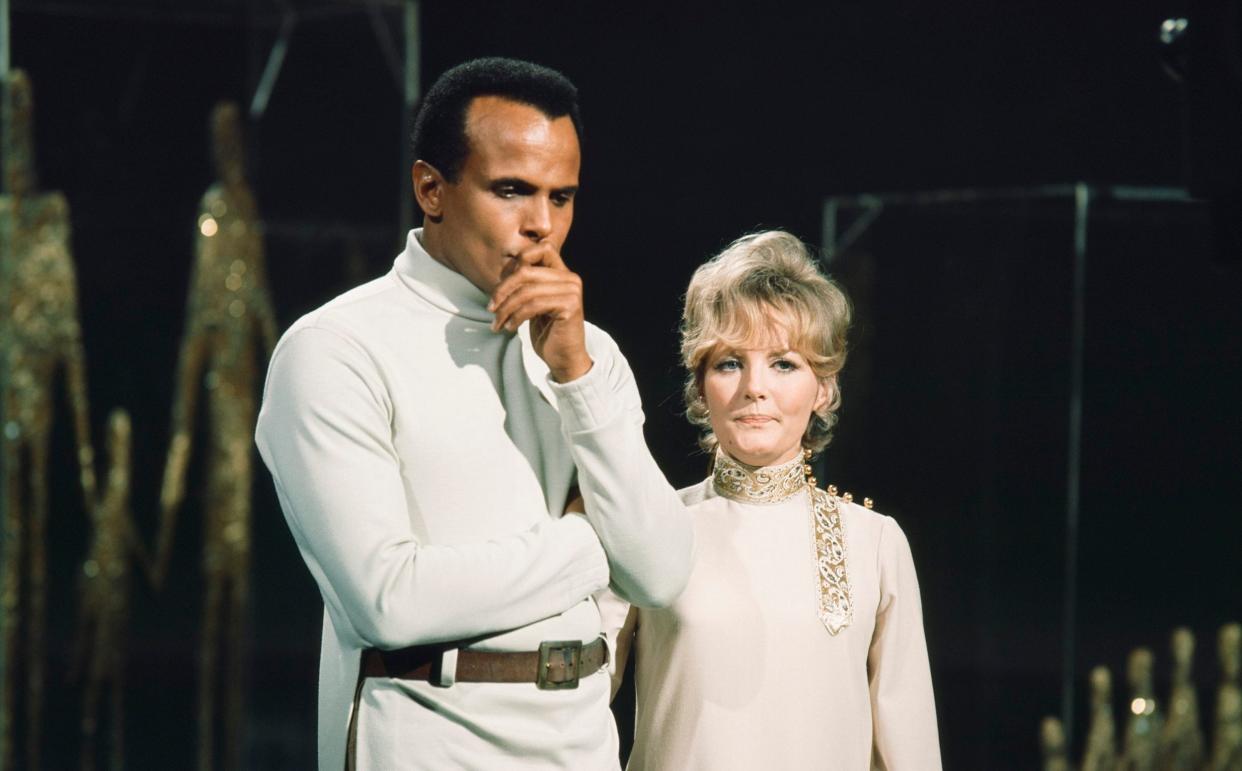

When Belafonte and Clark sang their duet, Clark lightly touched Belafonte on the arm. This small physical gesture led to an angry outburst from Lott, and initially even Belafonte feared that this would cause excessive controversy.

“I didn’t hear all the rumpus that was going on upstairs in the control area,” Clark would later say. “Touching his arm was just instinctive because we felt strongly about the subject. I just didn’t think about it.”

As Belafonte later recounted in his autobiography, he suggested to Clark that they redo the performance. “Perhaps, I told her, we should pick another fight, another day – at least while her best interests were at stake. ‘Forget my best interests,’ she said. ‘What would you do?’ I grinned. ‘I’d nail the b______.’ ‘So we will,’ she replied.”

While Poitier might have sought to be amelioratory, either asking for the performance to be reshot or keeping quiet about the actions of those around them, Belafonte publicly denounced the actions of Lott before the show was even broadcast as “the most outrageous case of racism I have ever seen in this business”.

He refused to accept Lott’s subsequent apology, saying: “Apologies in these situations mean nothing. They change neither that man’s heart nor my skin. Inside, he feels the same way because of how I look on the outside. He can apologise for the balance of his life but it won’t alter the attitude he has today. And a man with such an attitude has to be exposed.”

A few years earlier, there might have been outrage directed towards Belafonte, and the moment duly became an international news story, covered in the likes of Newsweek and Time magazine. Yet it was believed that he was a victim of the racism that he had spent his life campaigning against, and when the show aired – with Clark insisting that it be shown uncut or that she would withdraw permission to have it shown at all – it attracted high ratings and cemented Belafonte’s position as the most committed and courageous activist of his generation.

It proved a particularly bitter irony that, two days after the special was aired, its impact was overshadowed by the assassination of Martin Luther King; Belafonte was later photographed at his funeral next to King’s widow Coretta.

Throughout the rest of his life, Belafonte was unafraid to use his fame and cultural impact to espouse causes that he believed in. Some of these were more universally popular than others. His anti-apartheid views were held by most of his peers, but his consistent praise for Fidel Castro and his regime in Cuba caused him to stand apart from the political mainstream. When he attacked the Iraq war and Bush’s secretaries of state Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice, the latter was driven to say: “I don't need Harry Belafonte to tell me what it means to be black.”

Nonetheless, in 2006, Belafonte was asked what single epitaph he would like to be remembered by, and he said “Harry Belafonte, Patriot.” Few would disagree with this.