The Untold Story Behind the Most Famous Photo of Jackie Kennedy

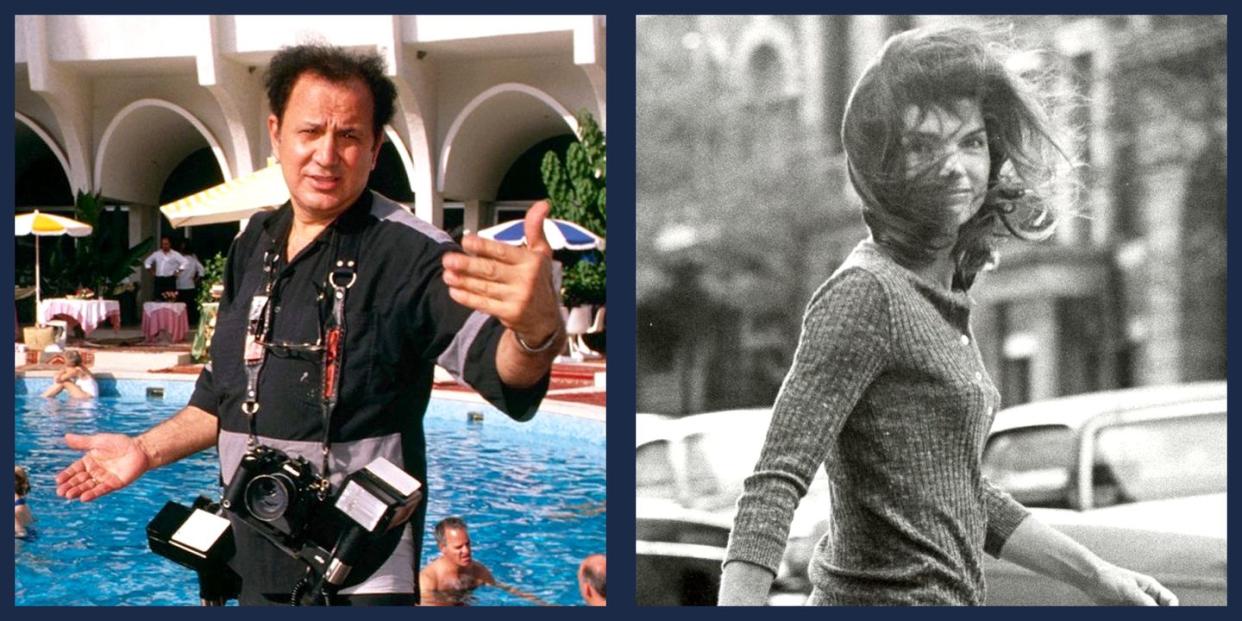

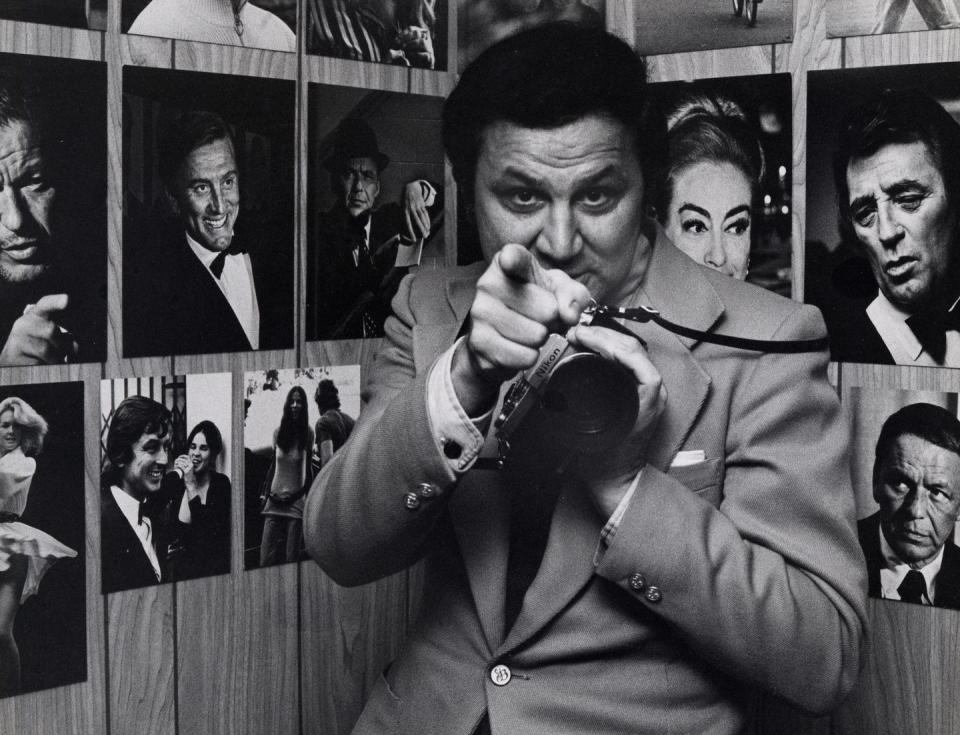

“I consider myself a great photographer,” says Ron Galella. “The greatest living photographer now,” he revises, then thinks on it for another moment. “The most famous. Google who’s the best. They’ll say Ron Galella. I mean Avedon and Irving Penn were great photographers. But they’re dead.”

It’s a cold, sodden afternoon in early 2019, and Ron Galella sits in a wheelchair in his room in a rehab facility in Lincoln Park, New Jersey, white hair fuzzy and uncombed. He's there because he fell out of bed at home, shattering his left femur. “The surgeon put screws and a plate, so it's healing pretty good,” he says.

The accident introduced an impediment to the tireless self-promoter’s efforts on behalf of his latest memoir-slash-photo book, but rather than rescheduling, Galella invites me to speak to him while orderlies deliver pills and hospital food and physical therapists pop their heads in.

At 89, he remains the only paparazzo most people know by name; he is mostly retired but still photographs the Met Gala every spring. His 20th book, Shooting Stars, is in his lap, dozens of Post-It Notes poking out, denoting talking points for his greatest career hits—stalking Jackie and Liz, getting belted by Brando among them. (Since this interview he has published his 21st, Costume Galas and Parties 1967-2019, and is working on his 22nd, tentatively titled The '80s.)

When not in rehab, Galella lives alone in a mansion in New Jersey. (It is where he's waiting out the coronavirus pandemic, with the help of a home health aide.) The entire first floor is a gallery of huge framed prints of his most famous images. The basement is stuffed floor to ceiling with his meticulously catalogued archive of photos, shot between 1952 and the present. It’s a staggering body of work, three million images taken by Galella and the 15 or so different photographers he employed over the years to be where he couldn’t.

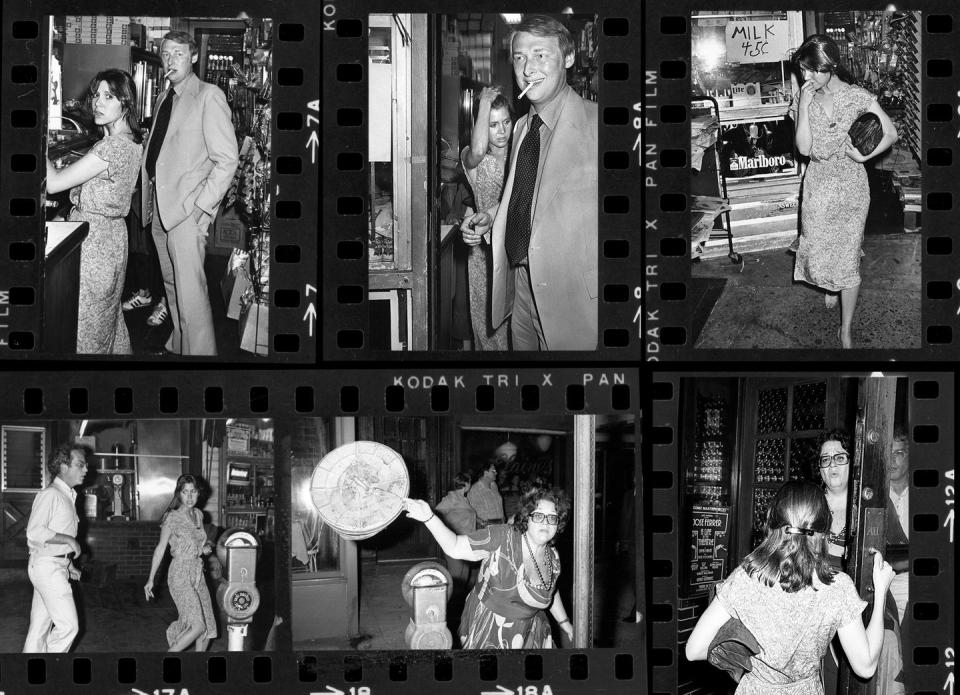

The archive is a testament to the fleeting nature of celebrity; a large portion of the files are labeled with the names of the once famous, or never-quite-famous, head scratchers like Phil Vandervoort and Dawn Lewis. Galella’s first rule was “shoot everybody” regardless of whether he actually know who they were. The frames he took of a couple of sexy randos at a 1975 Doobie Brothers party in Beverly Hills? “Guess who it was?” he says. “Don Johnson, 28-years-old, with Melanie Griffith, 18-years-old, before they were anybody!”

I remark that the silk pajama top he’s wearing in rehab looks like it might have come out of Hugh Hefner’s closet. As with any celebrity mention, this occasions a Galella tale of crossed paths and his status as “Paparazzo Extraordinaire,” the honorific he uses for himself and tends to call out aloud when he’s being photographed. “I was at the Playboy Mansion twice,” he says. “Lee Solters, the publicist would invite me because they know that my pictures get published. So he introduced me to Hugh Hefner, and Hugh Hefner says, ‘You're a celebrity in your own right.’ That's what he said!”

Galella unabashedly equates fame with success, and so it might not be surprising to learn that he’s a devoted Trump fan. His 19th book, 2017’s Donald Trump: The Master Builder, an opportunistic title he quickly produced after the 2016 election, is an admiring collection culled from his 32 years shooting Trump and family, and features Trump in a tux atop an illustration of a big gold escalator on the cover. “The only thing I don't like him for is he doesn't believe in the green,” Galella says, by which he means Trump’s environmental policies. (Galella’s Bronx accent and verbal shorthands sometimes yield amazing results. The French actress from The Umbrellas of Cherbourg? “Catherine Da Nerve.”)

He’d scribbled a personal inscription for me in the Trump book: “Let’s hope our president builds that wall!”

Beyond fame, Galella has, later in life, also earned the trappings of mainstream artistic recognition. An admiring documentary about him, 2010’s Smash His Camera, played Sundance and HBO. His work is shown by New York’s prestigious Staley-Wise Gallery, which also represents photographers like Richard Avedon, Helmut Newton, and Herb Ritts. Six of Galella’s works are in MoMA’s permanent collection.

Three of MoMA’s images come from one three day period in October of 1971, and portray Galella’s longtime prey and favorite subject, Jackie O, whom Galella pursued so aggressively over two continents that she went to court twice to stop him from following her and her children John and Caroline.

Galella’s Jackie legacy is complicated. His photos are revered by those who worship the iconic first lady for her poise and style, but according to Jackie herself, they came at an immeasurable cost to her own psychological well being. Galella, she testified, was ruining her life, his constant presence lurking outside her Fifth Avenue apartment and following her as far as Greece meant she had “no peace, no peace of mind, was always under surveillance, imprisonment in my house.”

Galella finally stopped in 1981, not out of compassion or boredom, but because a judge promised he’d throw Galella in jail for 60 years if he got anywhere near the former first lady. It’s this controversial association that made him the most famous paparazzo in the world and cemented his reputation as something of a charming sociopath, possessing an obliviousness clear even to his admirers.

“I think Ron's a guy that had no moral compass,” says Etheleen Staley, who first showed his work at her Staley-Wise Gallery in 2008, and is of the opinion that many of his images should be considered art. “He didn't see anything wrong with pursuing somebody, hounding somebody, not being respectful of a person’s privacy. It just didn't go into his head that you shouldn't do that. I think that's the secret of his success, that the boundaries that a lot of people feel didn't occur to him.”

Galella’s unrelenting pursuit of his subjects helped spawn an entire industry that treats celebrities as prey. Princess Diana’s 1997 death highlighted the real world danger of celebrity stalking, but back in the ‘60s and ’70s, when Galella was staking out Jackie, his pursuit was seen as a cultural curiosity, more rascally than predatory. Conversations about consent and the traumatic effects of a man pursuing a woman against her will were still, for the most part, decades away.

Post #MeToo, hearing Galella frame his pursuit of Jackie as a game of seduction is particularly jarring. Galella has referred to Jackie as “my girlfriend, in a way” and still maintains that despite taking him to court twice, Jackie secretly enjoyed the attention. He describes in breathless terms one of the few times she addressed him directly: “She comes out of the 21 Club with Ari Onassis and she approaches me, grabs my wrist, pushes my elbow against a limousine and says, ‘You've been hunting me for three months now,’ in a whispered voice. Yes, I was shocked that she said that. And she looked angry,” Galella continues. “I believe she liked to be pursued. She’d go to Jersey for those hunts with the fox and the horses, and she felt that I had pursued her like I hunted her. The press got it wrong. She liked being pursued.”

Galella's own childhood may explain his ability to conflate romance with antipathy. Growing up in Williamsbridge, on the northern edge of the Bronx, he remembers his parents fighting constantly. He recalls his father Vincenzo as an unsophisticated cabinetmaker, an Italian immigrant who spoke little English, while his Hoboken-born mother, Michelina, was consumed with the glitzier aspects of American life—fashion and celebrity. “My mother was Americanized, liked glamour and my father just liked… wine,” he says.

Michelina got naming rights on the third of their five children and called him “Ronald” after the dashing, British-born actor Ronald Colman; Galella writes that she came to favor him “because I was more handsome than my brothers.” Vincenzo, whom Michelina eventually exiled to the basement of their home, would get snockered on homemade wine and stay up all night drunkenly preaching to his children on the importance of making and saving money, a lesson repeated so often it apparently took; Galella never really drank, and his late wife Betty would often say that “Big Daddy,” as she called Galella, was “as tight as the bark on a tree.”

For a time, Vincenzo kept a rabbit that had been gifted to him in the basement, where its white fur turned grey from the coal used to fire the furnace. The children became enamored with the pet. One day, Vincenzo cooked it in a stew. “We cried,” Galella says, with a shrug. “He was foreign.” Galella, who never had children, would populate his estate in Montville, NJ with rabbits—both living ones and rabbit-themed tchotchkes, and a small cemetery, populated by rabbit statues, houses the remains of his six bunnies, “Pooper,” being his first.

Galella discovered photography in the Air Force. Anticipating he’d be drafted during the Korean war, he enlisted in 1951 and took his first photography lessons while being trained in camera repair. After reading glamour photographer Peter Gowland’s book, How To Photograph Women, Galella decided photography would be a diabolically good way to meet girls. (Galella claims he was shy back then, despite his current spaniel-like gregariousness.) After discharge, he used the GI Bill to fund his way through art school in California.

He made his first real money shooting kids with Santa at Christmas time in a discount department store in New Jersey (an avocation that would reemerge years later, when, realizing that no-one had shot Jackie O with Santa Claus, he hired a Santa to follow her through the city while he pursued). Galella began crashing movie premieres to shoot famous people and learned that there was a hungry market for such shots with down-market celebrity magazines like The National Enquirer and Photoplay. In 1970, he abandoned the Santa gig and became a full time paparazzo.

If there’s a chip on his shoulder, it’s about privilege and status. His was a career built on selling to publications what he termed “no appointment” portraits of the often unwilling for $25 a piece, the going rate for magazines and tabloids in the '70s and '80s. Meanwhile, Avedon and Irving Penn earned thousands to shoot willing models and actors in the comfort of a studio, a process that Galella deems criminally easy. “They were studio photographers and I'm glad that I didn't have the money to get a studio,” Galella says. “I could do studio photography but it was best that I was forced to make the world my studio. There's no other photos that's as great as my paparazzi photos.”

Galella never scrimped getting the shot. “Ron would shoot a whole roll maybe to get one frame that he really liked it and he could sell,” says his friend George Bernard, a longtime National Enquirer reporter who was often a copilot in Galella’s car. “The others were cheap, counted the pennies, wouldn't take many shots. Ron played the averages. He knew that if he kept shooting, he would get the right picture and he did invariably.”

In 1979, at 48, he married 31-year-old Betty Burke, a photo editor for a Washington, D.C.-based Sunday supplement called Today Is Sunday. He used to call her in a professional capacity, and her soft, sultry voice had initially reminded him of Jackie’s. They finally met face-to-face at the Washington premier of Superman. “I danced with her at the event, and then I shacked up with her in a hotel,” Galella says.

The married five months later (Tiny Tim came to their wedding), and Betty joined Big Daddy in the car with her own camera, pursuing the likes of Katharine Hepburn; she would soon take over all aspects of his business. The couple moved on up from a Yonkers duplex a few houses from Galella’s mother to their white palace in Montville, NJ, which Galella dubbed Villa Palladio. (Galella would eventually install a star with his name and his handprints in front of the house, because, he once wrote, “the Hollywood Walk of Fame doesn’t honor still photographers.”)

“She was a very good businesswoman,” he says of his wife. “She made me rich, really.”

In 2004, his knees shot from his decades spent in hot pursuit, he gave up shooting to devote his time to what he calls “a harvest of my life”—writing books and overseeing the digitization of his vast basement archive of 3 million images for Getty. Betty, a lifelong smoker, died in 2016 of emphysema. “She died in her sleep, thank God,” Galella says. “She didn't suffer. She was on the oxygen. I brought her the tray of food. I put it on her bed. I figured she's going to eat later, and I go back, and she was dead. She never touched the food. She was my love.”

Galella authored an entire book on what he calls the “Paparazzi Approach,” a phrase he trademarked. It enumerated 22 distinct techniques but could probably be boiled down to one of Galella’s favorite words: “balls.”

From the start of his career, Galella sported a size 5XL pair. Case in point: In 1968, Jane Fonda gave birth to daughter Vanessa Vadim at Belvedere Hospital in Paris. “So I did something that's got a lot of balls,” he says. “I knocked on her door in the hospital, and say, ‘Jane, Jane.’ I hear a shower, so I say let me go away, because it's a bad time.”

He eventually got the “Madonna” shot in front of the hospital, after which Roger Vadim sped away from Galella in a sports car with his wife and baby. “He went over 100 mph, this fuck!” Galella says. I suggest that there could easily have been a horrible, Diana-style accident. “I know!” Galella says. “He's crazy!”

He once told a writer that the only celebrity to ever shake him was Julie Christie, “going 90 miles an hour along a cliff in Malibu,” and boasted that he “passed ten red lights chasing Mia and André Previn when they were hot.” Galella’s bag of driving tricks included employing what he dubbed the “paparazzi lane”—gunning it into the right hand turn lane—to rush in front of traffic.

Funerals are most certainly fair game. “I did Lee Strasberg's funeral, even at the grave,” he says. “Al Pacino was there.” He did have a kind of vampire’s sense of decorum. “I've never gone into a house, unless I'm invited,” he says. Pools, however, were fine, and in 1971 he staked out Doris Day’s on Crescent Drive. After 30 days of seeing nothing, he finally discovered the actress in a bikini and got her “through the bushes with a long lens,” which became a four-page spread in Photoplay.

As was often the case, Galella didn’t take a photo credit to preserve his anonymity, but the secret was apparently too delicious to keep. “Years later, she came out with a book at Brentano’s in New York, and I said, ‘I was the photographer who shot those pictures,’” he says. “I had balls!”

Thirstier actors willingly played the game in exchange for the exposure. In 1968, after knocking on Natalie Wood’s door in Beverly Hills, the actress appeared and said, “I’ll be ready in five minutes,” and came out and posed in a cute tennis skirt and white boots and invited him to come shopping on Rodeo Drive with her.

But most of his subjects felt the invasion of their privacy keenly. In 1969, Galella packed some sandwiches, some cream soda, and gave a watchman $15 to lock him for a weekend in a customs warehouse full of cocoa and cat-sized rats that happened to have a perfect vantage point over London’s Thames River. He covertly shot Liz Taylor and Richard Burton aboard their yacht, the Kalizma; the National Enquirer paid him all of $400 for the shots.

Two years later, crewmembers on the Taylor/Burton vehicle Hammersmith Is Out, shooting in Cuernavaca, Mexico, discovered Galella trying to shoot Burton from inside a hotel pool pump house and exacted revenge. Galella ended up in a Mexican jail, but not before the crew confiscated his film and beat him up, breaking a tooth and splitting his lip. He’d lose five teeth—and win a $40,000 settlement—in 1973, after Marlon Brando belted him as he followed he and Dick Cavett through Manhattan’s Chinatown. “My paparazzi germs infected his hand, and he almost bled to death!” Galella says, delighted. “He spent three days in the Hospital for Special Surgery getting his hand fixed up.”

One of the most famous Galella photos wasn’t actually shot by Galella himself. The following year, Brando appeared at New York’s Waldorf Astoria Hotel to launch a charity for Native Americans, and Galella was there, with a customized football helmet emblazoned with “Ron.” Galella’s assistant dutifully took the iconic frame of a glowering Brando in a crushed velvet blazer ignoring Galella’s pursuit. His battles with Jackie—by then, already in full swing—had taught him that being part of the story could be good for the Ron Galella business.

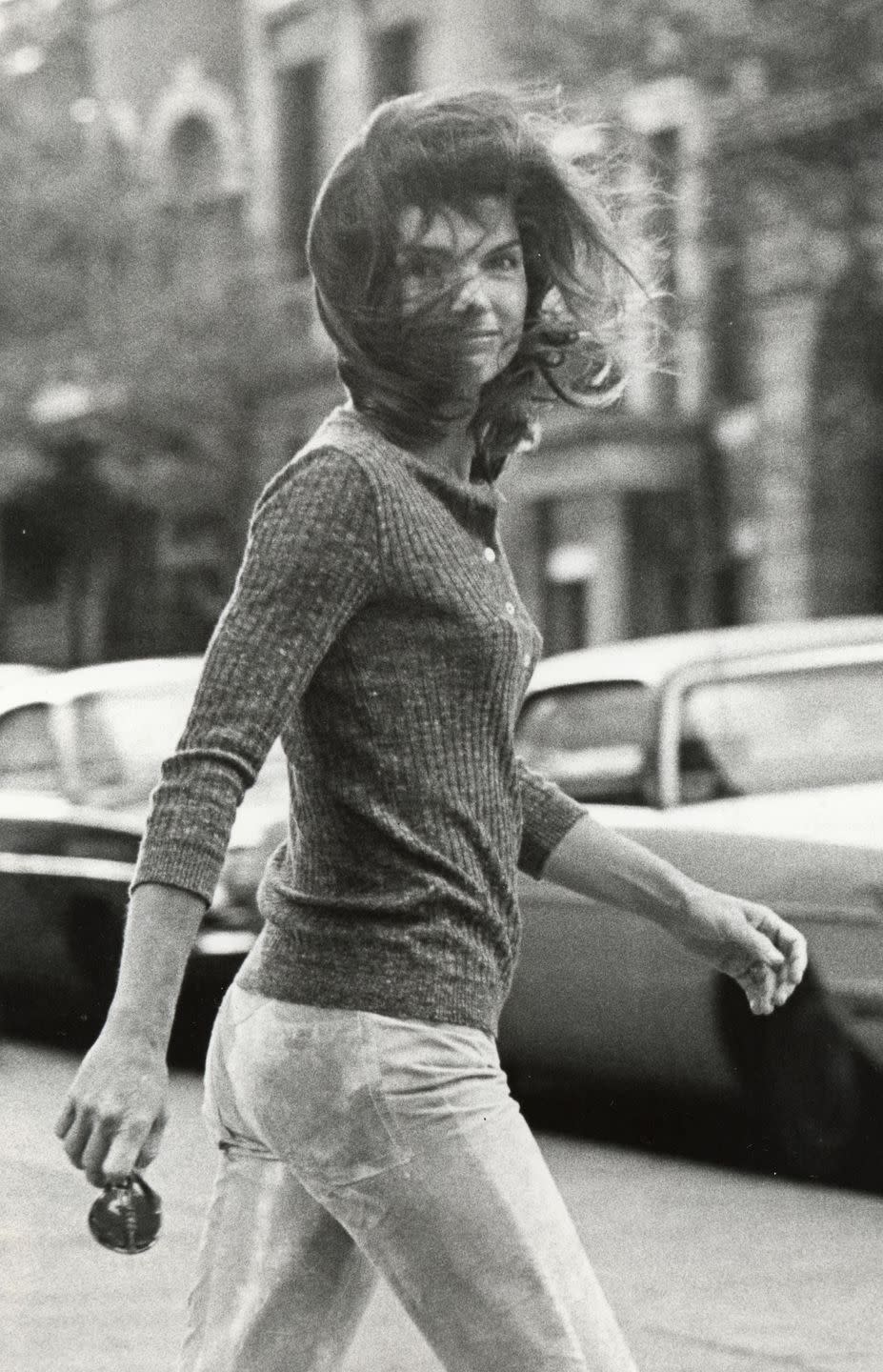

Despite the small percentage of his work that the Jackie images represent, they are undoubtedly Galella’s legacy—his “Windblown Jackie,” which he considers his masterpiece, is the print Staley-Wise sells the most of; the largest prints go for as much as $10,000. He took it on Madison Avenue from the back seat of a taxi on October 7, 1971, and unlike most photos he took of her, which feature either a pasted-on smile or a frightened-deer expression, in this one Jackie looks at the camera with a genuine expression of amusement.

“She didn't recognize me when I took the picture,” he explains. “The camera was blocking my face. So, she didn't know it was me.”

Jackie was by then firmly on record despising him. Since 1967, when he’d learned that she lived at 1040 Fifth Ave, Galella had taken to showing up at her house every day, often donning disguises—fake moustaches, hippy garb and afro wigs. He’d followed her into Broadway theaters, her son’s school Christmas pageant, and a Chinese restaurant, where he shot her from behind a coatrack. He dated her young housekeeper and pumped her for intelligence. He followed her to Capri, and Skorpios, and disguised as a Greek sailor, shot her sister Lee Radziwill doing yoga on the beach and Jackie swimming off of Aristotle Onassis’ yacht, the Christina O.

In September 1969, Galella leapt out of the bushes in Central Park to capture Jackie and eight-year-old JFK Jr. biking—according to Jackie, John nearly rode into Fifth Avenue traffic out of fright—and Jackie, according to Galella, shouted “smash his camera!” Secret Service agents handcuffed him and drove him to the nearest police precinct. He sued on first amendment grounds.

Aristotle Onassis approached him on Fifth Avenue and asked him what it would take to settle the matter. “A million dollars,” he told Onassis, and then sent the couple a Christmas card bearing the image of an Onassis look-alike in a Santa outfit, Galella on his lap, receiving cash. Jackie countersued, and in 1972, they came face to face in court, and she testified what it was like to leave the house knowing Galella was there.

“He lunged at me and he was grunting, and he was saying ‘Glad to see me back, Jackie, aren't you, baby?’ And then he took his camera strap and he was flicking me on the shoulders.” (Galella says he’s not a grunter, and never once flicked her.)

Galella’s justification for his obsession didn’t help: It came up in court that he’d told Ari Onassis that he thought his daily stalking of Jackie would “help her forget” the trauma of sitting next to JFK when he was assassinated in Dallas. A judge eventually ruled that Galella would need to stay 25 feet away from Jackie, and 50 feet from the kids.

In 1974, Galella published his first book, Jacqueline, in which he confessed, “I don’t want to take pictures of Jackie nude. In hot pants, yes. In a bikini, sure.” He confesses to me if he’d encountered Jackie in the raw, he naturally would have taken the shot, “but probably not released it,” as a Greek paparazzo did, when he sold a grainy nude sunbathing shot from Skorpios to Hustler in 1972.

In Jacqueline, Galella swore off shooting Jackie, musing sadly, “I don’t know if Jackie thinks about me anymore. Maybe she does… Does she miss me? Who knows,” but then the following year he flew to Los Angeles, posing delightedly three feet away from Jackie’s head with a measuring tape prop marked “25 Feet” and “Keep Your Distance.” In 1981, Jackie went back to court and enumerated Galella’s violations, and a judge ruled he’d be fined $120,000 dollars and jailed six years if he ever shot her photo again.

Galella has his defenders who claim that even if Jackie didn’t quite protest too much, she could have diffused Galella’s interest by occasionally giving him what he came for. And that as a famous person, she was fair game. “Jackie made a big mistake,” photographer Harry Benson says. “All she had to do was say, ‘Good morning, Mr. Galella,’ stand for a second, and walk slowly away. And she didn't. She ran. Her movement gave him a photograph. I always thought that the court case was unfair, you know? She was out in public.”

Galella maintains that Jackie secretly loved the attention and his work, claiming he had it on good authority a book he’d sent her were among her effects when she died. I share this with James Kalafatis, one of the Secret Service agents on Jackie’s detail. “What a crock of shit,” he emails. “I would say this was a manifestation of his paranoid delusion in which he felt she was his girlfriend. I will only say that in the many conversations I had with Mrs. Onassis (and Mr. Onassis) she detested him and found him repugnant.”

Before the trial, Galella’s Jackie obsession was seen as such a pleasant cultural curiosity. It landed him in 1971 a “Jackie Watching” cover and six page portfolio in Life magazine. The trial turned him toxic, into a villain. There is a photo of Elaine Kaufman throwing a trash can lid at him after he tried to shoot Richard Dreyfus in front of her eponymous Upper East Side restaurant, with an expression of revulsion on her face. Kaufman, like much of the rest of the world, treated Galella as one might an especially aggressive raccoon.

That reputation that largely stuck with him until 2002, when curator and editor Steven Bluttal dug deep into the archives to produce The Photographs of Ron Galella, which collected his best work from 1965 to 1989. It is precisely the hurried, invasive quality of his photos that has earned them artistic recognition. “Ron had always been not well liked, always sort of in the gutter with everyone, but I thought it was time for the snapshot aesthetic and paparazzi photography to be sort of highbrow,” Bluttal tells me.

Gucci sponsored its print run and Tom Ford wrote the introduction, acknowledging that Galella’s images had long served as an inspiration for his fashion and that “ironically, the very photographs that Mrs. Onassis resisted were the ones that defined her as an icon.” Over time, Galella’s method had become an aesthetic, and collectors felt comfortable spending large sums on them as works of art, no different than portraits of willing subjects.

Diane Keaton, one of Galella’s targets, conceded in her forward to The Photographs of Ron Galella that after looking at his collected work, she was grateful that he was there to annoy her and her famous friends, capturing them looking their unrehearsed best, noting, “to see Warren Beatty and Al Pacino in Ron Galella’s book is to be reminded of how remarkable they were. Now they, like me, are older.”

At Bluttal’s behest, Graydon Carter finally let Galella inside the Vanity Fair Oscar party. Gucci dressed him. A couple years later, Michael Kors, captivated by the book, acquired a number of Galella prints and titled his 2004 line, “Galella Glamour.” Soon the galleries and documentarians began calling. His knees and back were giving out by then, but Galella had finally arrived, just in time to retire.

As for Jackie, he’s now willing to entertain a dark suggestion Aristotle Onassis once offered many years ago on Fifth Avenue. “Maybe Jackie looked upon me as a sniper shooting her, like Oswald,” he says. “I can't know that. It's a psychological thing that's a mystery. We don't know what she was thinking. But I don't think so. Because the photographs show she's smiling, pleasant, positive. So, I feel that I was doing no harm, that I was doing good.”

For Galella, the camera’s gaze is all that matters in end.

You Might Also Like