Old School Jewelry Heists Are on the Rise

It happened in broad daylight, just before 10 a.m. on January 3. A team of burglars entered the exhibition of rare Indian jewels on view at the Palazzo Ducale in Venice and left with two items valued in the millions of dollars. One, a set of diamond earrings, featured two 30-carat teardrop-shaped centerpieces, each arrayed amid a chandelier pattern of dozens of smaller diamonds. They were almost modest compared to the second piece, a giant confection of a brooch, in which a 10-carat flawless diamond was saluted by rows of rubies, more diamonds, and tassels of strung pearls.

While many of the contents of the exhibition, more than 270 pieces of jewelry from the collection of Sheikh Hamad bin Al Thani, of Qatar’s royal family, were antiques (some dated back 500 years, to the Mughal Empire), the two stolen works happened to be modern. They had been purchased just a few years earlier from Viren Bhagat, a jeweler in Mumbai. According to the Associated Press, Al Thani was drawn to their modern style, “the unique, minimal platinum settings that make it look as if the jewels are floating.”

Float they did. The thieves may have numbered as few as two: a lookout man and another who quickly and effortlessly managed to open a fortified glass case “as if it were a tin can,” as Venice’s chief of police was quoted as saying, then slipped the goods into his pocket. The display had been designed by the sheikh’s own foundation and used at each previous stop on the collection’s tour: the Grand Palais in Paris, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the Met in New York, and the Miho Museum outside Kyoto. This was the final day of the collection’s four-month stint in Venice.

The burglars did nothing to make themselves invisible. The whole operation was captured by security cameras, which also recorded them leaving the museum, before they vanished into the throngs of tourists in the Piazza San Marco.

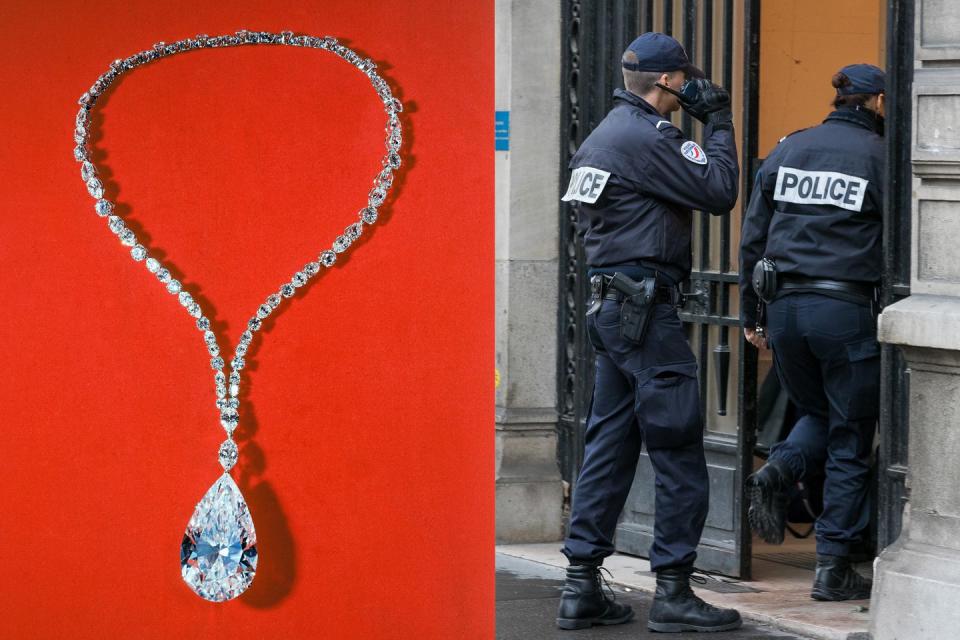

Just a week later thieves hit the jewelry shop inside the lobby of the Ritz Hotel in Paris and made off with an estimated $5 million in merchandise. This one was a smash-and-grab: They used sledgehammers to break open the glass display cases. They were also armed with guns and knives; they fired some shots and were in and out in a couple of minutes. Predinner patrons at the hotel’s Hemingway Bar retreated to the basement. The culprits fled on motorbikes. Three were caught and arrested, but two escaped. Despite the modern world’s obsession with security and all the scientific advances devoted to ensuring it, old-fashioned jewelry heists continue to occur and continue to arouse alarm. Part of the reason for their prevalence, experts say, is the enduring appeal of the bounty. “There’s always a market for fine jewelry, and typically you can take the entire inventory of a store and put it in a duffel bag,” says Jacque Brittain, digital editorial director at LP Magazine, a publication for the loss prevention industry.

But other factors are at play, including our society’s new open access, social media–driven lifestyle. “People just don’t realize what they open themselves up to by being public about certain kinds of assets,” says Christopher Falkenberg, the founder of the NewYork–based Insite Risk Management. There’s also the Robin Hood element of this kind of crime, which has long made it appealing to movie executives as well as criminals. (Ocean’s 8, Hollywood’s latest jewelry heist caper-staged at the annual Met Gala-stars Cate Blanchett and Sandra Bullock. It opens in June.) “It’s almost normal for people to see the theft of luxury objects as a victimless crime,”says Simon Atkinson, a former British Army officer trained in covert operations who now works for the Glasgow-based Athena Security & Intelligence Consultants. “The public often do not have a great deal of sympathy for those who flaunt what they own.”

One way to understand modern jewelry heists is to take a look at who is committing them and where and who the targets are. Security experts are quick to mention nerve as one thing that sets these crimes apart from other thefts, whether the act in question unfolds in plain sight or via invisible Rube Goldbergian machinations. The whereabouts of expensive caches of jewelry are frequently already known to the public: behind the glass in a store or a museum, on the shelves in a vault or storeroom, even on a person’s hands or neck. Guarding it, therefore, is usually front and center in the owner’s mind-something prospective robbers know from the start.

“The recent cases in Europe certainly demonstrate a degree of brazenness,” says Christopher Hagon, a former Scotland Yard officer who spent years protecting the royal family. (He now runs Incident Management Group, a security consulting firm based in Florida.) “The attackers circumvented security purely by being outrageous, by seizing the objects in an unanticipated way.”

Consider some of the major jewelry robberies that have occurred over the past few years. In 2016, Kim Kardashian was held up in Paris at gunpoint by two men (part of a gang of low-level French criminals ranging in age from their mid-fifties to their seventies) who stole an estimated $10 million in jewelry, including her 20-carat diamond engagement ring, two Cartier diamond bracelets, a gold Rolex watch, diamond earrings from Lorraine Schwartz, and a gold and diamond Jacob necklace. Kardashian was staying in a private apartment at the anonymous No Address Hotel at the time and had traveled to France with an entourage that included a personal bodyguard. She was surrounded by people almost constantly during the trip, but the thieves managed to target her during a brief moment when she was alone.

In 2015 a squadron of mostly geriatric burglars managed to make off with about $30 million in jewels, gold, and cash from an underground vault at the Hatton Garden Safe Deposit Company, in London’s diamond district. In 2013 an armed thief stole a sack containing gemstones and watches worth $136 million from an exhibition room at the Carlton Hotel in Cannes, where the jewelry was to be featured at a promotional event. The hotel, by the way, was the setting of the classic Alfred Hitchcock heist film To Catch a Thief. Also in 2013, robbers stole approximately $50 million in gems from a twin-engine jet as it sat on a runway at Brussels Airport. (The jewels had just been transferred from a Brink’s armored van and were bound for Zurich.)

All this might be enough to make you wonder if the Europe of today is like something out of The Pink Panther, or at least a New Gilded Age version of it. (In fact, the largest band of criminals-which has its origins in the former Yugoslavia and is made up of hundreds of loosely affiliated jewel thieves believed to be responsible for more than 400 heists all over Europe since 1999-is known as the Pink Panthers.)

Here in the United States, the most enterprising jewelry thieves have been less cinematic in technique, but their resourcefulness can still be seen as a nose-thumbing to the retailers and brands that make their names catering to the one percent. Between 2012 and 2014 a ring based in Detroit committed a string of robberies around the country, which were followed by dozens of arrests. Their focus: Rolex dealerships, for obvious reasons.

And there was Abigail Lee Kemp, “the Diamond Diva,” a 24-year-old former lingerie model and Hooters waitress from a privileged background who in 2017 was convicted of going on an armed robbery spree of jewelry stores in five states. Her weeklong string of holdups, it emerged in court, had followed a carefully scripted playbook provided by three older men-one of whom, her boyfriend, followed her into jewelry stores with a gun while she stood lookout. In a series of rehearsals at an auto body shop in Atlanta owned by the other two men, they chose Kemp’s outfits (casual exercise clothes), taught her how to use zip ties to bind clerks’ wrists, and developed a list of code words to use during the act.

If the recent rash of crimes has a common thread, it’s something that might actually be a silver lining for jewelry lovers: Many of the culprits are on the old side and endowed with a tolerance for risk and chipped nails that their would-be successors have failed to inherit. “Criminals younger than 40-like most people their age-would rather not have to perform on the ground,” Atkinson says.“They’re interested in electronic scams, white collar crimes like identity theft and credit card fraud. You can rob a bank in Moscow without leaving your living room in San Diego.”

One can’t help marveling at the preparation that goes into some heists. “The level of planning the big jewelry cases depend on is phenomenal,” Atkinson says. “The first part is broad target selection, looking at dozens of potential targets via open source research. Then, from that they’ll pick a couple of them and do detailed reconnaissance and surveillance.” This means casing the joint-taking pictures of the premises, making drawings of escape routes, figuring out the location of security cameras, and determining the gaps in protection. “Generally, if you pick a high-profile target, you’ll come up on someone’s radar. That’s what made the Hatton Garden case so remarkable.”

Hatton Garden-the London street and commercial district that housed the industrial-grade vault that was attacked-is a location synonymous with valuable gemstones, the United Kingdom’s answer to the jewelers row on West 47th Street in NewYork City. The 2015 burglary was so intricately choreographed that for months afterward it was assumed that responsibility for it lay with the Pink Panthers, who are known for military speed and tactics. The fact that the culprits turned out to be a bunch of aged ex-cons beset with Crohn’s disease, artificial hips and nicknames like “The Gov’ner” and “Billy the Fish” made their caper all the more surreal.

Along with diamond-tipped drills, wire cutters, walkie-talkies, and a white van, some of the other equipment they put to use included utility worker uniforms, the book Forensics for Dummies, and a senior citizen discount bus ticket.

Their maneuvers involved gaining access to the building via a fire escape door that was opened by a redheaded man (according to closed circuit cameras) whose identity remains unknown, getting past an iron gate and disabling the electronic alarm system, and boring three overlapping holes through a reinforced concrete wall so that the skinny perp who was able to shimmy through the opening could gain access to...a steel wall. When the men realized their efforts had not gotten them inside the vault but merely reached the back of a cabinet of safe deposit boxes that was bolted to the floor and ceiling-and when they were unable to pry the cabinet free with a 10-ton hydraulic ram-they left the scene for two days. Two quit, but some returned with a newly purchased ram that they used to dislodge the cabinet, then cracked open 73 of the vault’s 996 safe deposit boxes with crowbars and sledgehammers.

The loot consisted of loose diamonds and sapphires in large quantities, bundles of cash, and gold and platinum bullion. Nine men were arrested in the case the following month; eight were convicted, one acquitted, and at least one-the redhead-is still at large, along with two-thirds of the haul, worth more than $15 million.

The Brussels Airport heist, by contrast, unfolded with razor-like precision, all during the 18-minute window between the moment the jewels were loaded onto the plane and takeoff time. Eight masked men, armed with assault rifles and dressed as police officers, ordered the pilot and crew to stand by while they methodically took about 120 boxes of diamonds from the hold. No shots were fired. They sped away in vans that had been rigged with blue police lights. The authorities eventually charged 16 men and three women with carrying out the robbery and helping to hide the gemstones, most of which have not been recovered.

And the lone gunman who pulled off the Carlton Hotel robbery in Cannes? He walked away with a bag without incident and was in and out of the building in less than 60 seconds. Many reports put forth the theory that he couldn’t have acted alone and must have had inside help, and some noted that just three days earlier one leader of the Pink Panthers had escaped from a Swiss prison. It wasn’t quite the perfect crime-the perp slipped and dropped the entire haul as he made that exit (through a window), then quickly scooped up the items of greatest value and ran away. Still, the case remains unsolved.

These burglaries involved such complex and painstaking efforts on the front end that it’s not difficult to understand Hollywood’s tendency to slap “the perfect crime” on movie posters. A simple safecracking story, on the other hand, would have to work a lot harder to justify a three-act plot.

In To Catch a Thief, Cary Grant plays a reformed cat burglar whom the police suspect in an ongoing wave of jewel robberies on the Co?te d’Azur. To clear himself, his character, John Robie, has to return to his old milieu and nab the actual villain red-handed. He tells the insurance agent he drafts to aid him in his pursuit that he is no Robin Hood, but he still can't help rationalizing his crimes: “For what it's worth, I never stole from anybody who would go hungry.” When the righteous Lloydsman, played by John Williams, calls him “frankly dishonest,” Robie says, “I try to be.” He is all but imputing a degree of blame to anybody whose possessions he relieved them of. After all, jewelry’s worth is so closely bound up with the person who wears it. And perhaps its very showiness, its status as the most non-essential of luxury objects, serves as a dare: Those comfortable enough to afford such riches and gaudy enough to show them off are asking for trouble.

That perspective, albeit with a modern twist, is used by many to explain Kim Kardashian’s ordeal in Paris. In the weeks preceding the robbery, the reality TV star posted numerous pictures of her engagement ring and other jewelry items on Instagram. Once she arrived in France, regular coverage by paparazzi, as well as her own social media updates, showed her at events and parties, which made her whereabouts easy to track. Even the bodyguard was compromised by the camera. Personal security staffers are theoretically more effective when they remain anonymous, but Kardashian had recently joked on one of her social media accounts that he was “always getting in the frames of pictures.” At the time of the robbery he was accompanying her high-profile sisters to high-profile parties.

“Kardashian was letting the world know what she owns and where she was going at virtually every moment,” Christopher Hagon says, which is exactly the kind of behavior a high-net-worth individual should avoid. “I mean, how much do you hear about Jeff Bezos traveling around? How often do you see pictures of him standing in front of his own jet?” Christopher Falkenberg points out that Kardashian was in fact fortunate she was traveling with such valuable goods. “It was a very dangerous situation she was in and would have been worse if she hadn’t had the jewelry to give them.” Falkenberg stresses that pride in one’s jewelry (as in the old adage about fools’ names and fools’ faces) is best never registered in public places, including party pages and social media feeds. “I think there are many people who have difficulty dealing with all the moving parts of a very affluent lifestyle,” he says.

While the Kardashian case was covered extensively by the media, many jewelry thefts do not make it into the public eye-often because of who committed the crime. When it comes to jewelry, experts agree that security begins at home, especially if there’s staff. “In Manhattan, theft by building employees is far more common than people let on,” Falkenberg says. “We’re constantly brought into the fanciest apartment buildings to investigate a loss, and in many cases the perpetrator turns out to be an employee of the co-op or a household employee.” From May to July 2013, for example, a rash of at least four jewelry burglaries was reported in different apartments at 740 Park Avenue-the building believed to house the highest concentration of billionaires in New York-on the third, sixth, and 14th floors. ( The New York Post’s coverage, which name-dropped some of the hedge fund managers, investors, and heirs who live on those floors-David and Danielle Ganek, Ezra Merkin, Spyros Niarchos-added that the police estimate of the value of the loot at $250,000 might be low: “There could be further stolen items that were never reported because the residents are so wealthy that some might not have even noticed that some of their valuables went missing.”)

Whether the thieves were on the pay-roll or not, the history of jewel robbery is full of friendly perps-and our fascination with them is of long standing, apparently. In 1964 the New York Times ran a feature titled “The Aristocrats of Crime,” which quoted an insurance investigator’s estimate that America had about 4,000 “good” jewel thieves (“good in the sense of highly professional”) and then asserted that of those, only 100 or so were the elite “ ‘masterminds’ who operate on an international scale, who are capable of stealing almost any jewel in existence, and who come romantically close to emulating Raffles, the cool, suave, inscrutable jewelry thief of fiction.”

A real-life archetype was Arthur Barry, a gentleman cat burglar of the 1920s who was believed to have stolen more than $10 million in jewelry and was known for crashing black tie parties at mansions on the north shore of Long Island. “Wandering upstairs, he would make a mental note of the floor plan, seek out likely places where jewelry might be kept, and unlock half a dozen strategically placed windows,” the Times said. “If noticed, he would skillfully feign drunkenness and pretend to be looking for a bed.”

In the 1990s we saw a variation on this model in Mitch Shaw, an old money Texan who, with his girlfriend as getaway driver, stole millions in jewels from some of Dallas’s richest homes. More recently came the Bling Ring, eight well-off young adults from Southern California who burgled jewels from the homes of a handful of young celebrities, including Paris Hilton, Lindsay Lohan, and Megan Fox. Though they never met their marks, the boys and girls of the Bling Ring blended into their environment easily enough; they began by driving to Hilton’s house in West Hollywood and simply locating a key under the doormat (they didn’t use it, because, even more simply, the door was unlocked). Hilton not only permitted the movie director Sofia Coppola to shoot scenes for The Bling Ring, her faithful adaptation of the events, at her home-she played herself in the film.

Is there a next generation of jewel thief waiting to take over with new methods and new technology? Probably not. Experts agree that the tactics-and, in some cases, the perpetrators-haven’t changed much in recent decades. Evidence? One of recent time’s most active jewel robbers (until she was caught-again-last summer) was Doris Payne. Age: 86.

When jewel thieves are caught these days, it’s often because they have exhibited the same traits as their victims: carelessness, vanity, lack of restraint. “Criminals may be smart when it comes to operational planning,” Simon Atkinson says,“but the unintelligent ones are often caught because they flaunt what they’ve done: buying expensive cars and posting pictures of them on Facebook. It also makes it easy to find informants.” The biggest challenges involve fencing stolen jewelry and dismantling the most significant pieces to sell as loose stones. “You’ve got to be able to turn the jewelry into cold cash. Anything from a high-profile robbery cannot easily be sold on the open market, because legitimate traders will question the source of the items. A lot of these burglars don’t want to wait 10 years for the temperature to go down.”

How, then, can you protect your jewelry? After the recent heists, collectors and purveyors of jewelry alike have wondered about the efficacy of modern security systems. Fair enough, says Timothy Bradley, a former FBI agent who specializes in corporate and travel security at Incident Management Group. “A place like the Ritz in Paris might have a higher-technology alarm system, but that’s not necessarily something that can prevent a low-tech theft. Any solution to protect valuable assets can be studied and defeated.” For Christopher Falkenberg, the answer is prudence: “You don’t want to be quoted praising a fancy jewelry store, and you don’t want to be photographed wearing fancy jewelry. To spread information about the assets is not sensible.”

This article appears in the May 2018 issue of Town & Country. SUBSCRIBE TODAY

You Might Also Like