There’s No Excuse for Buying or Decorating With Blackamoors

The design world, like many industries, has faced a much-needed reckoning over the past several months as important conversations about race, diversity, and social justice rose to the forefront of American consciousness. The conversations have happened and continue to happen at House Beautiful, too. We are learning, evolving, and looking more closely at the role we’ve played in injustice and what we can do to contribute to equality moving forward.

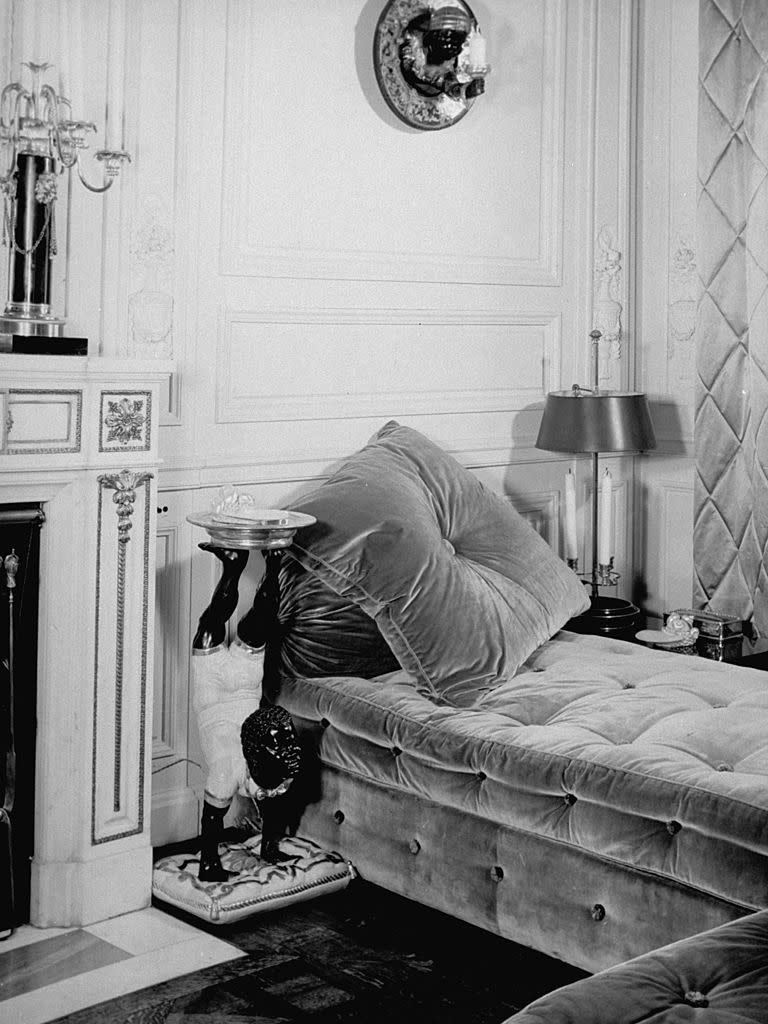

One of those actions is to call out art and decor that, no matter its stated intention, is rooted in racism or bigotry. Among them: the Blackamoor, a depiction of a dark-skinned person—generally a slave or servant—of Moorish descent, which is used as ornamentation. Blackamoors can be found in the form of jewelry or in pieces of home decor. No matter the context or time period of the object, though, the motif is one that is undeniably damaging.

“They might have become synonymous with Old World luxury, but these items exploited servitude as ornamentation,” says Adrienne L. Childs, PhD, an art historian, curator, and author of the forthcoming book Ornamental Blackness: The Black Body in European Decorative Arts.

Blackamoors began appearing in European decorative arts in the 17th century. “They became popular in aristocratic homes, including the court of Louis XIV, at a time when Europeans were engaged in the slave trade. The notion of the ‘exotic’ Black body became a symbol with Baroque ostentation,” Childs says. Early Blackamoor figures, made from expensive ebony and silver, were almost always shown in servile positions—as as the base of a table, or supporting a candelabra, or even acting as a seat. “Basically, they were used as figural supports, the same way that you might have seen a dolphin or a cherub holding up a table.”

Their popularity continued throughout the 18th century; in the 19th century, an entire industry of more cheaply made Blackamoor decor—"kitschy knockoffs of the originals," says Childs—emerged in Venice. And by the 20th century, as American designers embraced the neo-Baroque movement, they also embraced the Blackamoor. “It’s something you might see in a Park Avenue apartment as a throwback to that time,” Childs notes.

It was within this exact context that House Beautiful recently included an image of a room that contained a Blackamoor, specifically a table with a sculpture of a dark-skinned person as its base. While the image and its story were reviewed by many staffers, the table was not spotted until after publication—and we were sickened when it was brought to light. This oversight has reminded us that our efforts have not been enough: House Beautiful must take a stronger stance identifying such motifs and using our platform to eliminate them from the American design vernacular.

While collectors might argue that an antique Blackamoor figurine is more a celebration of 18th century European craftsmanship than an endorsement of the slave trade, the way they represent Black bodies is unquestionably grotesque. “The fine materials, the ‘beauty’ of these things, they all divert from the very troubling nature of what you’re really seeing, which is an enslaved body,” says Childs.

Surprisingly—or perhaps not—Blackamoor decor is still widely available, both as newly made items (most often coming from Italy) or via antiques dealers. But that’s beginning to change: This past June, the Winter Show, a major art and antiques fair in New York City, announced that it would no longer be displaying Blackamoors or other racially insensitive items (like blackface or Mammy dolls) at its yearly event. Christie’s and Sotheby’s similarly removed such objects from their catalogs, and many digital antique dealerships have imposed similar strategies.

To remove these objects from auction blocks, antique showrooms, and House Beautiful’s own pages does not erase their damage, nor does it sweep their troubled history under the rug. These changes make clear that Blackamoor figures have no place as ornaments in the home—they were unacceptable items of decor in the past, and they are unacceptable today. House Beautiful deeply regrets the inclusion of this image, and will take steps to ensure such hurtful imagery never appears in the magazine again.

You Might Also Like