Michael Ball: ‘Young people should get a grip – actors can’t work from home’

Michael Ball is describing how he reads music. Or rather, how he doesn’t read music. “I can see where the melody goes up and down. I can see which notes are longer than others. But ask me what a baritone is and I haven’t got a clue.”

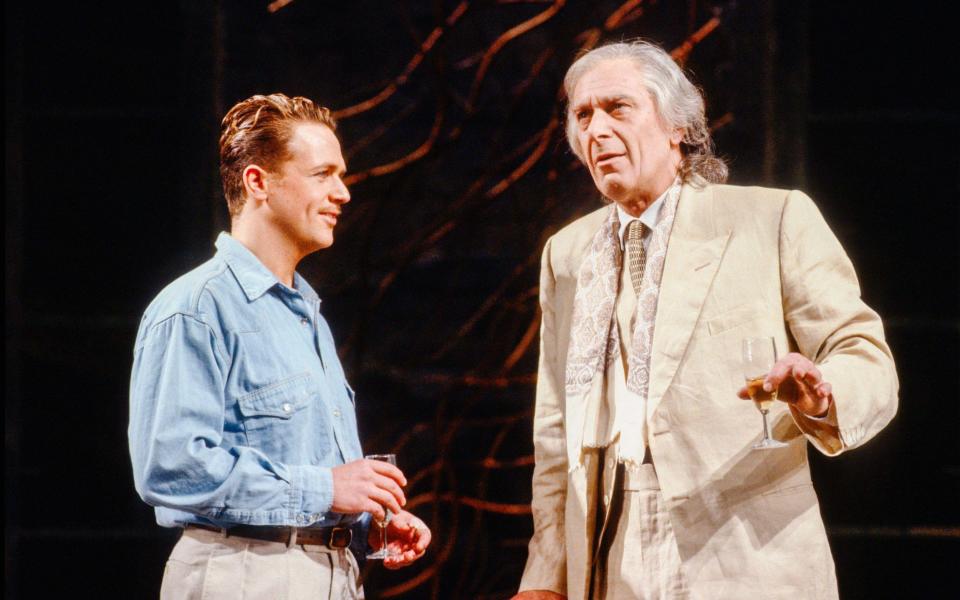

The man who had a smash hit single in 1989 with Love Changes Everything has had precisely two singing lessons in his entire life. “I’m a terrible student. But I do have an instinct.” Instead, he learns by ear. Play him a tune and he’s got it. Love Changes Everything was written by Andrew Lloyd Webber for his 1989 musical Aspects of Love, which made Ball a star, and Ball once suggested that the second time the song is sung in the show, the melody ought to go up at the end. “Andrew said ‘What? To B flat?’. I said I’ve no idea. But he agreed I was right.”

Some singers hate being defined by the song that made their name. Ball, 60, is not one of them. We are sitting in a pub in Barnes, near where he lives, to talk about his new memoir, Different Aspects, which splices his career to date with an account of his ill-fated attempt earlier this year to revive Aspects in the West End.

The production closed early after three months, felled by poor sales, and Ball is heartbroken. He thinks the show’s subject – which in its original version includes a romantic entanglement between a 15-year-old Jenny and Alex, her mother’s former lover – put people off. “Icky is the word people kept using,” he says.

Ball is certainly not one to shy away from critics: in 2022 Marianka Swain wrote a piece for this newspaper expressing strong misgivings about the proposed revival, calling the plot “queasy”. The piece led to anxious meetings with the show’s producer Nica Burns, and the decision was made to raise Jenny’s age to 18. Marianka, says Ball in his book, had “put the cat among the pigeons”.

Now he says: “Actually, in raising Jenny’s age, I had worried we were sanitising the story. But I think Aspects is simply too close to home for people. No one wants to think about their teenage daughter being looked at by a dodgy member of the family.” Yes, but doesn’t the musical romanticise that idea? “Sure, but in the show that potential relationship doesn’t happen,” he says. “Some shows are simply of their time. To be honest, Aspects was never a great hit anyway.”

Ball is full of candid, off-the-cuff observations like this. They litter his memoir, an intimate self-portrait delivered in the same chummy banter with which he speaks.

There are some amusing behind-the-scenes tales, from the cast playing ‘hunt the squirrel’ during performances of Les Miserables, in which he starred as Marius in 1985, to Gillian Lynne instructing Roger Moore how to dance with the useful advice “nipples to the stars, bumholes to the back”. Moore, who had been cast as George in the original Aspects, audibly struggled with the score during the rehearsals and “sensing Andrew wasn’t happy” fell on his sword two weeks before the show opened, to be replaced by the understudy, Kevin Colson.

There is also a brief reference to the composer Joe Brooks, who wanted Ball to star in a musical version of Metropolis, and who was later accused of several “casting couch rapes”; he killed himself in 2009. Has Ball ever witnessed anything similar during his career?

“I can only speak from personal experience but no, not at all. But musical theatre is a very tactile profession. People strip naked in the wings [during costume changes] all the time in order to keep the show moving. You don’t give a s--t about showing your bits. And if you do, then of course that will be accommodated, but don’t miss your cue.”

There is, however, plenty about Lloyd Webber, with whom Ball has worked several times. For instance, his ruthless casting process, whereby Lloyd Webber would invite performers to workshop new material in front of an invited audience at Sydmonton Court, his country house, only to give the actual role to someone else. This happened to Ball who, having played Joe Gillis at Sydmonton during an early tryout of Lloyd Webber’s adaptation of Sunset Boulevard, which premiered in 1991, lost the role to Kevin Anderson.

“It’s awful,” Ball writes. “Andrew, if you are reading this, it’s awful.” Then there was the screaming fit during tech rehearsals for Aspects in 1989, during which Lloyd Webber – in a fit of fury – tore the score from the hands of conductor Mike Reed. “When the composer starts threatening to pull his score is when you really start to worry for the future of the show,” writes Ball.

There is also the unexpected fact that Lloyd Webber used to loan Michael Jackson his private jet. And my favourite detail: Ball singing Itsy Bitsy Teenie Weenie Yellow Polka Dot Bikini at Lloyd Webber’s wedding to his third wife Madeleine Gurdon in 1991. He sounds like a complicated person, I suggest. “Oh come on, don’t pretend you don’t know he is complicated!” says Ball. “But look, his legacy is extraordinary. He’s a genius. And the British public love him.”

In the book he says Lloyd Webber has always craved the critical reverence accorded to Stephen Sondheim. Does the fact critics tend to dismiss his work as lightweight hurt him? “He’s pragmatic. But yes, of course it does. We don’t do this job because we have something we absolutely need to share with an audience. That’s b------t. We do it because we want a Niagara of unqualified praise. Of course, we need critics too. But sometimes critics don’t understand a show. Andrew always writes and plays to the heart. And sometimes critics don’t seem to be able to say ‘this is something completely different’. Andrew has produced musicals that do something completely different all the time.”

Ball grew up singing to Ella Fitzgerald while never imagining a life as a singer could be for him. He boarded at Plymouth college from the age of 11 (his family lived in Farnham) but flunked his exams. “No one expected anything from me. Least of all me,” he says.

Nagged to come up with a career, he told his dad, who became head of sales at British Leyland, he thought he would like to become an estate agent. But he had also been attending Surrey Youth Theatre and a teacher there spotted his promise. An audition at Guildford School of Acting was hastily arranged, and he got in, much to the delight of his theatre loving father, who’d been taking him to the RSC for years.

On leaving Guildford, Ball almost immediately got a job in Godspell in Aberystwyth and then in Pirates in Penzance at Manchester Opera House. Roles in Les Mis, Phantom of the Opera and Aspects of Love quickly followed, his rich, unashamedly emotive baritone a perfect match for the era of the big romantic musical of the late 1980s. Since then he’s carved out a steady career in musical theatre alongside an equally successful one as a recording artist. He remains the Peter Pan of light entertainment – the original poster for Love Changes Everything carried the line: “Take Michael home for a Mother’s Day Treat” above a photo of Ball’s alarmingly youthful face, and honestly, 30 years on, he’s barely changed a bit.

Except it almost didn’t happen. In 1985, Ball left Les Mis after a bout of glandular fever incited a series of panic attacks on stage and then a catastrophic breakdown at 23. For months he mouldered in his flat, gripped by an “awful, terrifying” state of mind. It was only when Cameron Mackintosh rang to offer him Phantom (playing the love interest Raoul) that he saw a route to recovery.

“I had been ill-equipped to deal with what was happening. Imposter syndrome took hold. And I went into this spiral that got completely out of control. Back then depression wasn’t talked about. It was particularly hard because I’ve always tried to present myself as a positive sunny side up sort of person.”

He is deeply sympathetic to those, like him, who have suffered a mental health crisis. He is less sympathetic to what he calls “snowflakery”. In his book he doesn’t hold back on the younger members of the cast in the 2021 revival of Hairspray, in which he reprised his role as Edna Turnblad, who wanted to take time off because they were feeling “tired”.

“That would really get me. You’re tired, are you dear? Get a grip. I’ve done Hairspray in Dublin with buckets in the wings because I had Norovirus. In London one cast member actually left during the interval because they had a sore throat. You let the entire team down when you do that. Younger people don’t understand that getting the job is about seeing the job through. Acting is not a profession from which you can work from home.”

Ball lives with his partner of 35 years, the former TV presenter Cathy McGowan and shares McGowan’s daughter, Emma, from a previous marriage. Fresh faced he may be, but he worries about getting old. “Can you think of a musical role for a 60-year-old man?” Before I can reply he says “It’s why I diversify. There’s the writing [he also published his debut novel The Empire last year] and the radio show [he presents a weekly show on Radio 2]”. But he’s hardly out of work – next year he embarks on an extensive UK tour. They might not have flocked to Aspects of Love, but I can’t see the British public tiring of Michael Ball anytime yet.

Different Aspects by Michael Ball is out Oct 12 (Blink Publishing)