Meet the Black Women Who Rode Motorcycles Cross-Country to the March on Washington

Porsche Taylor is, as she puts it, “definitely being attacked by the road” right now. She’d hit rain in New Mexico (translation: slick roads and slow speeds). In Texas, her 80-mile-per-hour pace often not possible (traffic was merged into one lane due to construction). And pretty much everywhere in between, unlit highways meant not riding past sundown. Still, with only four days to get from Long Beach, California to Washington D.C. she was determined to stick to the itinerary. All 2,700 miles of it.

“Yeah we’ll need to pick it up and go a bit faster,” she says, speaking from the road, which thankfully, has opened up again. She’s cruising through big-sky country, passing by wide-open plains and dusty cattle ranches and…then she’s got to go. “I’ll call back once I maneuver around these big trucks,” she says. “I’ve got to get my girls past them or we could really get hurt.”

These are the realities when your ride is a candy-gold 2020 Indian Challenger—a motorcycle. Behind Porsche: a group that includes an EMT, a community college employee, a former member of the Army. One on a purple, three-wheeled Spyder, another riding a black and chrome Harley Davidson. All headed for the March on Washington with Black Girls Ride, a movement founded by Porsche to increase the representation of women in motorsports.

When they left from the west coast at 6 a.m. on Monday, there were just four women taking part in the cross-country trek, but two more joined in along the route. Once in Washington, they’ll meet-up with hundreds of other riders who all traveled from around the country.

For the women of Black Girls Ride, being on a bike is all about “wind therapy” and a sisterhood and a passion, but this time, they’re riding for something else. “After watching what happened to George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and so many others, it really stirred something up in us,” says Porsche, speaking from the road using a hands-free system that allows her to take calls from her helmet. “We knew we wanted to fight these injustices from the front line. I feel like I’m watching civil rights regress in this country and if we don’t stand up and speak up, we’ll be right back where we started.”

It was in Arkansas that the ride got especially emotional. There, checking into a hotel at the end of a long day of riding, the group heard the full story of Jacob Blake when a video of what happened to him appeared on television. “It was just a feeling of disbelief,” she says. “The thing is, I should have been outraged, but it happens so often that the element of surprise is kind of lost. It was just a reminder that this is what we’re fighting. This is why we’re riding.”

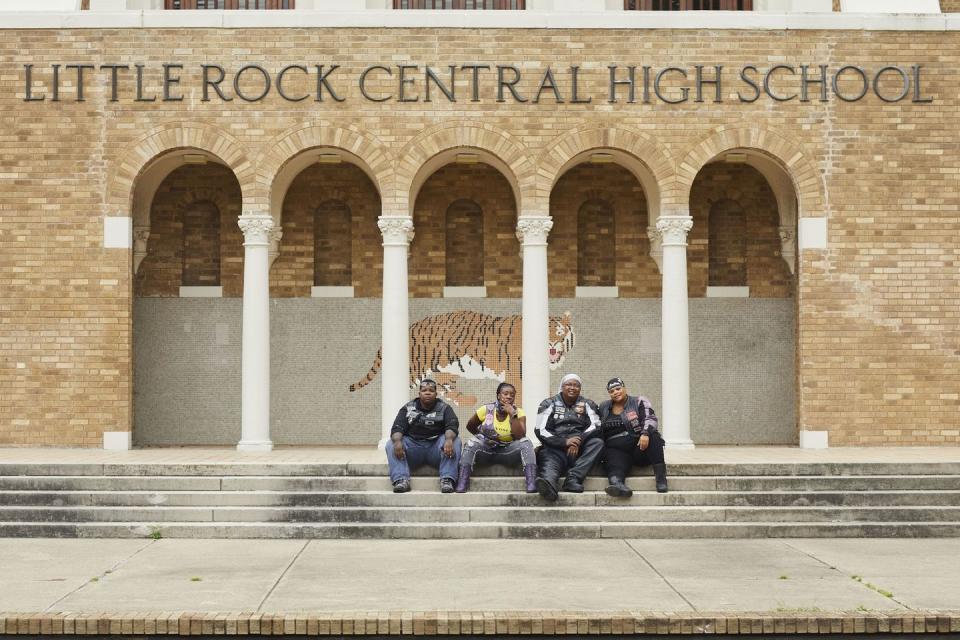

It was also there that they made time for a stop at Little Rock Central High School, which was forced to desegregate in 1957. “It was a really surreal moment for us,” she says. “We talked to a security guard who had been working there for 31 years. She told us the story of a young Black student who was spit on by so many people in the community as she walked to school that her dress was dripping with spit by the time she got inside. But she was not going to be bullied or deterred. This was a motivating factor for us to keep going. If these young people took it upon themselves to stand firm, we need to continue their work. As we take this ride, these thoughts are definitely on our mind.”

It's a constant balance, the heavy emotion with the physical exhaustion of riding for thousands of miles—the latter of which Porsche is used to, though. She’s driven across the country on her bike—to music festivals, events, or just to see friends—dozens of times.

“I have kind of a cheesy history of how I got into motorcycles,” she says. It happened after a trip with her cousin to see the movie Biker Boyz, a film about an underground group of Black motorcycle racers in Los Angeles. “The takeaway from that movie for me was the images of strong Black women riding their own bikes,” she says. “They weren’t accessories. They weren’t on the back. They were riding right alongside the guys.” It gave her a mind-bending idea: She didn't have to be a passenger. She could be the one in control.

It was around then that Porsche, who worked in marketing, got a big bonus. She would either spend it on a big-screen TV or a bike. “I obviously bought the motorcycle and never looked back," she says.

Soon she was hooked on the thrill of riding—the way you could feel speed, a physical force against your body—but as is often the case with thrill-seeking sports, Porsche realized that Black women were often overlooked. “The reality is, women, and Black women in particular, didn’t have a lot of representation in motorsports," she explains. "When you think of someone who rides a motorcycle, you think of someone middle-aged, white, and male. But Black women have always been in motorcycling, you just didn’t see us. Instead of complaining about that, I decided to be the change I wanted to see.”

Porsche quit her corporate job and started Black Girls Ride in January 2011. At first, as a magazine. A place to show the women who were active in motorsports and to add "diversity and texture" to the riding community. In just a few years, it become something bigger, a space for women interested in motorcycles to get together through meet-ups, rides, and and other events. It also became a way to create change.

“This is what’s so cool; I really believe motorcycles unite people, no matter your background, political affiliation," says Porsche. "If you see a cool bike, you’re going to stop and talk to the rider.”

Somewhere between Texas and Tennessee, Porsche was approached by a man wearing a Trump hat. “My bike, it gets a lot of looks because it’s the newest model and most people haven’t gotten a chance to see it in person yet,” she says. “So I'm talking to this guy about motorcycles and it’s all good and then he asks me where I’m going,” says Porsche. “I tell him I’m headed to the March on Washington. And he said, Wow okay, well you’ve got a really nice bike there, and he went on his way. We didn’t get into some big political discussion, but if as people we can find common ground on something as simple as biking, we can get to a place where we can find common ground on other things.”

With only 300 miles left to go, it’s not running late that’s worrying Porsche anymore. It’s what she’ll say when she gets there. Right before pulling out of town, Reverend Al Sharpton invited Porsche to speak at the March. While on the road, the details were confirmed: she would deliver a two-minute talk to the gathering of tens of thousands.

“It was like, whoa, this is a pretty big deal,” says Porsche. “My mind wanders back to the March on Washington 57 years ago when Dr. King stood in front of the crowd to give his speech about how he had a dream. I do believe we are a manifestation of that dream—I am, after all, a free Black woman motorcycling across the country unimpeded—but I also believe it’s our job to make sure that dream doesn’t turn into a nightmare.”

She used the long, seemingly-endless stretches of highway to come up with what she’s going to say. “I don’t want to let my community down,” she says. “But ultimately, my message is simple: We’re all here at the March because we’ve still got a long road to travel. And if we don’t start at Mile One—voting this November—we’ll never get to our destination.” This time, we can't just let it ride.

You Might Also Like