Matt Damon, Anthony Minghella, and the chilling power of The Talented Mr Ripley

On March 24 1997, Anthony Minghella reflected on the extraordinary journey that he had undertaken over the previous two decades. He had gone from being a PhD student and lecturer at the University of Hull specialising in Samuel Beckett, to that night winning an Oscar for his 1996 film The English Patient.

Thanks to the then-influential and powerful producer Harvey Weinstein, he was in the rare position that any truly successful filmmaker can be: the opportunity to make a personal picture with the enormous resources of a Hollywood studio behind him.

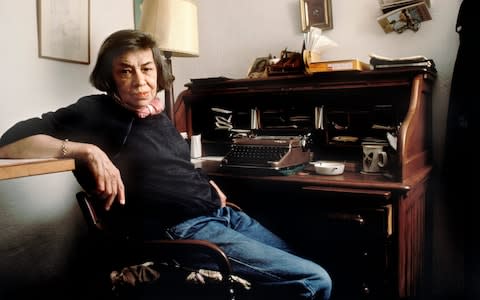

Others in his position succeeded admirably; some failed dismally. Michael Cimino’s all-consuming failure with 1980’s Heaven’s Gate, after his Oscar triumph in 1978 with The Deer Hunter, brought down an entire studio. Yet Minghella had no such vainglorious ambitions. He wanted to make the definitive film of one of his favourite books, Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr Ripley, and to transform a clever, chilling novel into something approaching great art. And he succeeded admirably.

Minghella had been thinking about an adaptation of Ripley for years, but now that he had Weinstein’s backing, he moved quickly. Reassembling most of the crew from The English Patient, several of whom had won Oscars for their previous work with him, he set about finding the right actors, aided by Miramax’s clout and a generous budget.

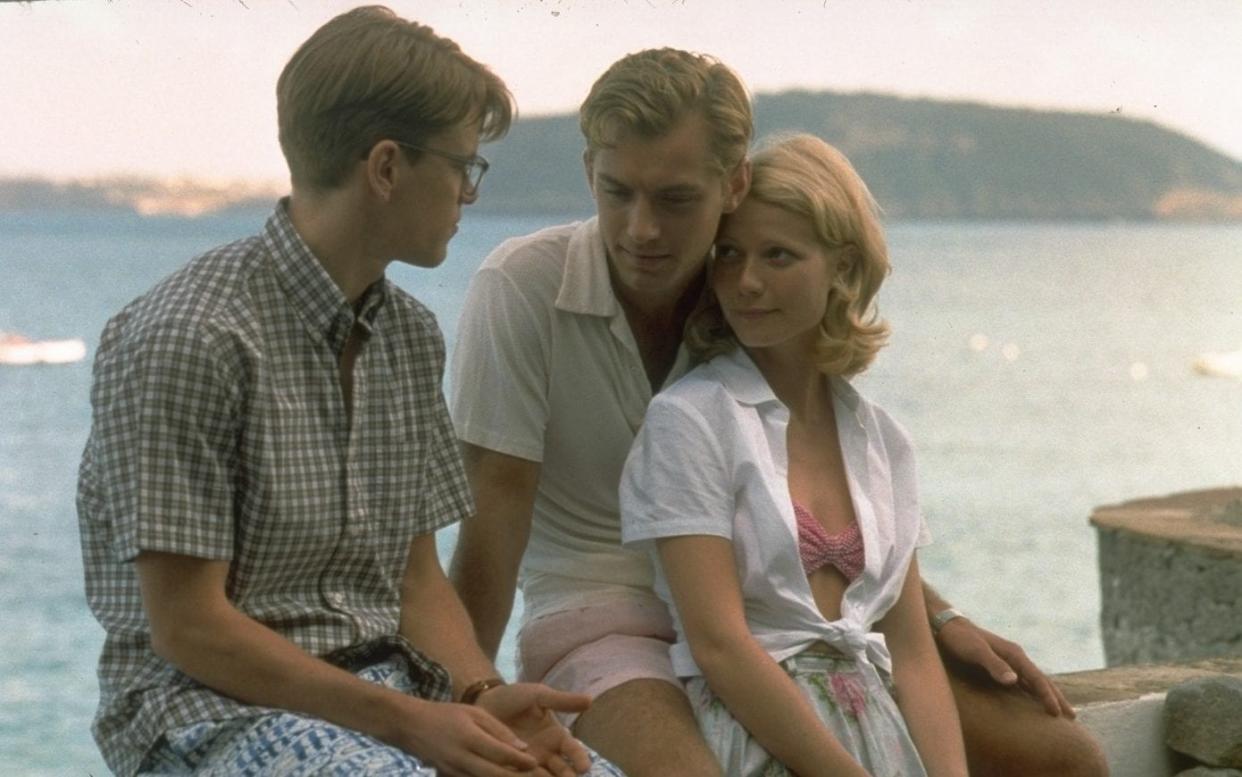

Initially he was interested in casting either Leonardo DiCaprio or (interestingly) Tom Cruise in the role of Ripley. But Matt Damon, after his acclaimed performance in Good Will Hunting, was Miramax’s golden boy, and Minghella saw something in him that would chime with his interpretation of Ripley – a boyish charm, hinting at a chilling capacity for violence and pain underneath. As Dickie Greenleaf, the object of Ripley’s imitative obsession, Jude Law was equally perfect, combining matinee-idol charisma with petulance and viciousness.

The rest of the cast, typically for Weinstein produc was peerless: Damon and Jude Law, of course, but also Gwyneth Paltrow, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Cate Blanchett and, to heartbreaking effect, Jack Davenport as Peter Smith-Kingsley, the only man who ever really loves Ripley for who he is.

They were lured in by Minghella’s script, a masterclass in adaptation that deftly and intelligently added nuance and shadings to the original novel. After filming throughout Italy, most notably Rome, Venice and Positano, in late 1998 and early 1999, Minghella finally turned in his cut of the film for its release in December 1999, at a time when virtually every week seemed to bring a major piece of cinema to the screen (Magnolia and The Green Mile were released in the same month).

He must have been disappointed by its initial reception, although he was too gracious ever to say so in public. Unlike the rapture with which The English Patient had been greeted three years before, the initial reaction to The Talented Mr Ripley was muted. Amy Taubin wrote in The Village Voice that Damon was miscast, sneered at Minghella as ‘a would-be art film director who never takes his eye off the box office" and, in an unintentionally prescient touch, observed "by the end, it’s like you’re watching the Andrew Cunanan story".

Although some critics understood that they were in the presence of greatness (Roger Ebert gave it his maximum rating and called it "as intelligent a thriller as you’ll see all year"), there was a general sense that it was just another elegant but ephemeral Harvey Weinstein production, and a step down for Minghella after The English Patient.

It was nominated for several awards and did well at the box office, with Jude Law attracting particular praise for his performance as Greenleaf. But Damon was regarded as too lightweight and limited an actor to do justice to the complexities of Highsmith’s character. It seemed the film’s ultimate fate to become a throwaway joke in Kevin Smith’s 2000 Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back, when Damon (as himself) is sneered at by Ben Affleck saying "I'm sorry I dragged you away from whatever gay serial killers who ride horses and like to play golf touchy feely picture you were gonna do this week."

Sometimes, brilliance can transcend a gag in a Kevin Smith film. When Minghella died, far too young at 54, in 2008, the obituaries universally recognised that The Talented Mr Ripley was his greatest and most significant achievement, trumping his Oscar for The English Patient and his other work, including Truly Madly Deeply and Cold Mountain. It was some small consolation to those who had – sometimes, it seemed, vainly – argued about the peerless quality of Minghella’s work.

Calling films masterpieces is often hyperbole, but in the case of The Talented Mr Ripley, it is richly deserved. Two decades on from its release, it is widely hailed as a modern-day classic.

I still remember the circumstances in which I first saw the film. I was living in a small village in Suffolk, where the trains to the nearest big town with a cinema only ran every few hours. I had calculated that I would leave the film 20 minutes early and make it home easily. It’d be diverting entertainment, I thought, but surely little more. I was wrong.

As I waited for hours on Ipswich station, I attempted to digest what I had just seen. It seemed to me then, and even more so now, an extraordinarily rich and complex film, an operatic study of the nature of obsession and evil and of how someone can lose their very soul along with the rest of their identity. Minghella received some criticism for turning a page-turning (and very funny) crime novel into something far more sombre and mournful, which is understandable but misplaced.

He retains the narrative’s reversals and twists, maintaining a Hitchcockian level of suspense throughout the second half. But there is something else at play too. The Talented Mr Ripley speaks to us more clearly in 2019, in our age of identity uncertainty, than it ever could have back in its own time. In an era where it is almost de rigueur to suffer from impostor syndrome, it is salutary to look back on the greatest impostor of them all, with both pity and terror.

Much credit has to go to Damon as Ripley. Somewhat overshadowed at first by Law, at the peak of his screen-idol days, Minghella carefully directed him to be somewhat akin to Ryan O’Neal in Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon. When the film begins, Ripley is a blank, a ventriloquist and a dummy simultaneously, whose mission to head to Italy to retrieve the wastrel Dickie is only given to him because of a moment of mistaken identity.

Yet once Ripley arrives in the country of jazz and sex, an identity of sorts begins to emerge, one largely driven by his infatuation with Dickie, who, amused by his faltering crush, simultaneously indulges and patronises him. When his friend tires of him and wishes to move on, Damon chillingly and brilliantly suggests the rage of a man who, emerging from his shell for the first time, is bluntly told to return inside it. He will not, and that leads to murder, before he is, like Macbeth, "in blood stepped so far" and cannot regain his humanity.

Its legacy is keenly felt. 2018’s excellent series The Assassination of Gianni Versace frequently seemed, in its laser-like focus on its psychotic yet resourceful anti-hero Andrew Cunanan, as if it was telling a similar story relocated to Miami in the 90s – albeit with the difference that it was based on fact - and the Oscar-winning writer-director Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck has not only cited it as one of his favourite films but has used everything from the Venetian setting to its creative personnel in his own work.

Highsmith-esque novels as disparate as Sebastian Faulks’s Engleby and Elizabeth Day’s The Party all owe as much to the film’s mood of stylish decadence as they do to the original book. And countless fashion designers have been quoted as saying they wanted to do something "a bit Mr Ripley" for their linen suits and Fifties-inspired dresses.

Minghella’s film was not the first time that Ripley had been portrayed at screen, nor the last. Alain Delon and Dennis Hopper had given their interpretations in 1960’s Plein Soleil and 1977’s The American Friend, and John Malkovich and Barry Pepper played him in, respectively, 2002’s underrated Ripley’s Game and 2003’s never-released Ripley Under Ground.

Recently, it was announced that Andrew Scott is to embody Highsmith’s great creation for an eight-part miniseries for the premium television service Showtime. It will be written and directed by Steve Zaillian, the Oscar-winning writer behind the HBO series The Night Of, and it will called, simply, Ripley. Expectations are high, given Scott’s ability to convey charm, menace and inner sadness simultaneously: three characteristics essentially for any interpretation of the character.

The bar has been set extraordinarily high for Scott and Zaillian in their new adaptation, but both men are capable of greatness. And I, for one, cannot wait to watch what they come up with – hopefully without any two-hour waits at train stations. But the curiously intense power of Anthony Minghella’s greatest film shows no signs of losing its grip on our collective imagination, two decades on. Time will tell whether Ripley can do the same.