Making The Lost Legends of Redwall: The Scout Anthology, and why size matters

The Lost Legends of Redwall: details

Publisher Soma Games, Forthright Entertainment

Developer Soma Games

Engine Unity

Release Out now

Formats PS5, Xbox Series X / S, PC

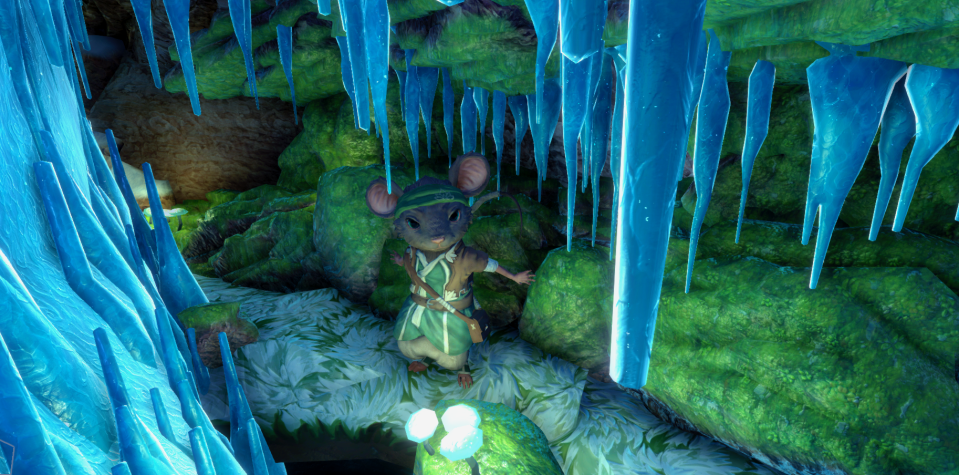

The Redwall books have sold over 20 million copies worldwide and is one of the most loved children's series of all time. So when Soma Games was tasked with turning this fantasy world, one in which moles, mice and other countryside animals battle against rats, weasels, and foxes within Redwall Abbey and the surrounding countryside of Mossflower Wood, it was an exciting but daunting task.

Soma Games' Unity-made adventure, The Lost Legends of Redwall: The Scout Anthology, released this week for all the best game consoles, so I sat down with two of its creators, executive producer Chris Skaggs and art director Erin Marantette.

What is interesting about the Redwall books is no single illustrator has defined the style, many have painted covers and interior art, such as Sean Rubin, Pete Lyon, Troy Howell and Gary Chalk, but they have all interpreted Brian Jacques' world in a slightly different way. For the Soma Games art team, this was something of a plus, as it meant Soma's artists could approach the game with fresh eyes.

"So there was at least an opportunity to start over," says Chris Skaggs, explaining it's not like Lord of the Rings where over the decades the art of Tim and Greg Hildebrandt defined Lord of the Rings to an extent Peter Jackson's film trilogy needed that as a reference. "Redwall wasn't like that, and so in that regard, you know, when Erin started working on this, she had a pretty free rein," he says.

Erin Marantette jumps in and explains there were some boundaries, for example when it came to the architecture of Redwall Abbey, and it was more a case of ignoring certain influences, such as the TV animation popular in America.

The biggest challenge the art team faced was turning the beautiful 2D illustrations and concept art that was being created into 3D models. Mice and other countryside animals, points out Erin are made up of simple shapes that can lose their readability in 3D. "[Learning] how to keep the appeal and charm of the 2D in the 3D is one of the harder processes, and it's a challenge, and it's when it's done right, it's great. It's beautiful. It's wonderful. But it's a challenge," she says.

For the Soma art team it was a matter of designing 2D character concepts to work in 3D, and this affected the character design. The team needed to ensure the mice and creatures of Redwall worked in 360 degrees and required "and extra bit of thought," says Erin.

Likewise, creating Redwall characters to work to scale was a big part of the game's character design. "No one could agree on how big these creatures are," says Erin, who tells me she spent a whole summer of "race work", designing non specific characters with the sole aim of determining form and proportions of the game's animals before any actual character design was done. She laughs and tells me, when you draw a mouse in its basic form it's "just a bag… Really a mouse is just a little circle with legs on it. […] If you get super-stylised a mouse is just a literal circle with a tail on it, and people know that's a mouse because it's so similar to the real thing".

That work early on developed into some key design ideas that subtly affect how players view characters in The Lost Legends of Redwall: The Scout Anthology. For example, all of the good characters in the game walk with their heels down, while all the villains walk with their heels up. This creates different walking patterns and animation styles for heroes and villains. Characters walking with their heels up "feel more unbalanced and more threatening because they're taller," says Erin, while characters walking with the heels down "feel more at peace, they are more settled, like the woodlanders are supposed to be".

Character designs also went through a "gut check" where the team would scan the art to ensure the game's animals didn't simply look like humans with mice masks on. The work to ensure animals look, feel and move like animals even when dressed in armour and walking on hind legs complex.

"It's a lot harder to do when you have to figure out a bunch of new animations and how that might work with the anatomy of a hare, because the hare doesn't walk on two legs naturally," says Erin. "We had to make sure we knew the limitations of how far into human versus how far into an animal-like skeletal structure we could go and find a balance."

Erin shares how the game's animal designs do break reality; they have, for example, ball shoulder joints as a necessity to make animation work (and really, mice don't usually carry swords).

Can't see the trees for the wood

"We went three through three different iterations of trees," laughs Erin when I ask about creating this aspect of the game. "Not just like, hey, here's one type, or here's one version, I'm talking about three different stylistic iterations, three different technologies," she says.

The nature of the The Lost Legends of Redwall: The Scout Anthology is it's set in a forest, and getting a complex alive woodlands to feel dense and natural, and keep the game's performance up across multiple platforms, is hard.

We wanted to do is make sure this place is beautiful and alive

"One thing that we wanted to do is make sure this place is beautiful and alive," say Erin. "And one thing that makes a forest look alive is having variation, which means you can't save by having the same model over and over."

She continues: "It means having different layers, it means having short bushes and tall bushes and then having short trees and tall trees, which means having different types of trees." The team also wanted aspects of the trees, like leaves, to be translucent… "That was a big tech question that took a solid, I think, five years just to get to our final solution."

Unity helped when it came to crafting the forest, but the team worked through a number of off the shelf solutions, including SpeedTree, until eventually simply modelling the tree and foliage themselves. In all there are around 15 variations of tree and foliage types that make up the game's forest, and all come in various shapes and sizes.

Why size matters in Redwall

Character and environment design and modelling comes together in an eye-opening aspect of Redwall: The Scout Anthology, and that's how this game uses size, scale and its game-camera.

"Because you're playing as a mouse, we want you to seem small, so everything is larger than it should be," says Erin, before bluntly revealing, "Our mice are about three feet tall. Our Badgers are about nine feet tall."

We are experiencing this world as if we are human child and that gave us a good frame of reference

That was unexpected. Erin giggles a little and shares that everything in the game is measured in "mice". This unique scaling system ensures a certain uniformity of scale to everything in the game, but importantly keeps the player centred, who controls the mouse.

Redwall is a series of books for children, and as such the team wanted their game to emulate how the world feels from a child's viewpoint - at three feet tall, or one metre, the game's mice are child-sized. "So we are experiencing this world as if we are human children and that gave us a good frame of reference for us as the artists. Everything should be slightly bigger, slightly too big." explains Erin.

Chris tells me this idea to use scale to immerse players in the Redwall world was inspired by the books' author who wanted his stories and fantasy world to be seen through the eyes of a child, "that became kind of a real keynote for us, like, let's really make that into 3D".

The Redwall: The Scout Anthology is out now for PS5, Xbox Series X, PC and Mac. If you're inspired by the work of Soma Games, read our guides to the best laptops for 3D modelling and our Procreate tutorials for game art and character design, and get started yourself.