The lost mansions of London’s riverside Millionaires’ Row

Behold that narrow street which steep descends

Whose building to the slimy shore extends

Here Arundel’s famed structure rear’d its frame

The street alone retains an empty name

There Essex’s stately pile adorn’d the shore

There Cecil, Bedford, Villiers – now no more.

For several centuries, before the Georgians built Mayfair and when Chelsea was little more than a riverside village, London’s wealthiest citizens lived on the Strand. So called because it ran close to the strond, or shore, of the river, from the 1200s until the 1700s it was lined with great palaces and mansions.

Linking the commerce and squalor of the City with Westminster’s corridors of power, and with direct access to the Thames, it was only logical that the capital’s aristocrats and bishops should build their homes here. Riverside views, a ready supply of fish, a clean and cooling breeze – what could be better?

The only sticking point was the quality of the road itself. In his book, London: A Travel Guide Through Time, Dr Matthew Green highlights a royal proclamation from the 14th century lamenting its “deep and muddy” condition, “so deteriorated and broken that... great danger is likely to ensue for both men and carriages”. Luckily, the river provided an alternative route.

With only one exception, all the Strand’s great houses have now been lost. Here’s what we’re missing.

Salisbury Inn

At the eastern end of the road, where the Fleet River joined the Thames (before it was culverted), sat the London house of the bishops of Salisbury, a complex of timber-framed buildings surrounding a large quadrangle courtyard, all bounded by a crenellated wall. To the east a vast garden rolled down towards the water. The bishops vacated the property in the 16th century, trading the land to the Crown, and the mansion was soon torn down. The only clue to its existence in the modern city are the street names: Salisbury Court and Salisbury Square.

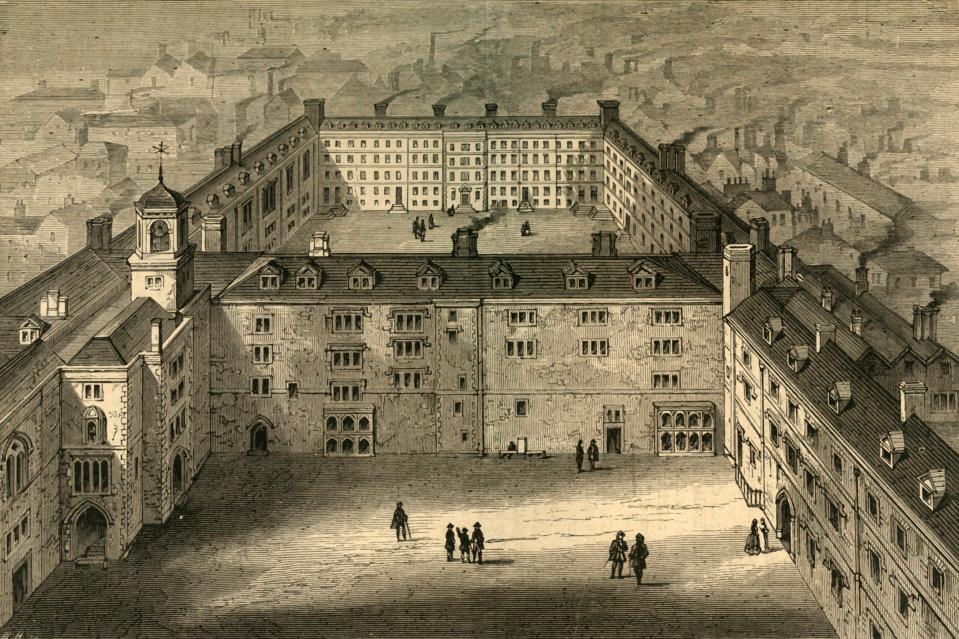

Bridewell Palace

Another property at the meeting of the Thames and the Fleet was Bridewell Palace, built at a cost of £39,000 – that’s around £40m in today’s money – on the site of medieval St Bride’s Inn. It was Henry VIII’s chief London residence between 1515 and 1523 and consisted of two courtyards and three storeys of royal lodgings.

The palace was leased to the French ambassador between 1531 and 1539 and one of its lavish rooms was the setting for Holbein’s famous 1533 painting The Ambassadors (on display in the National Gallery).

In 1556 Bridewell became a workhouse and prison. One book, White Cargo, tells how homeless children as young as 10 were swept from the city’s streets and held there before being shipped off with convicts to work as slaves in Virginia.

One of the prison’s most famous residents was Elizabeth Cresswell. The 17th-century brothel keeper who featured in contemporary literature and songs died within its walls. The young clergyman asked to perform the funeral rites reputedly said: “She was born well, lived well, and died well; for she was born with the name of Cresswell, lived at Clerkenwell, and died in Bridewell.”

The original Bridewell was gutted by the Great Fire but soon rebuilt. Its final chapter was as a school, before its was demolished in 1864. A rebuilt gatehouse in the style of the original is incorporated into the front of an office block at 14 New Bridge Street.

On the 21st-century map of London the location of the lost palace is marked by Bridewell Place, just off Tudor Street.

Exeter House

The first Exeter House was a little to the west of Salisbury Inn and built at the beginning of the 14th century for Walter de Stapleton, the Bishop of Exeter from 1308 to 1326, founder of Exeter College, Oxford, and twice the Lord Treasurer. He fell foul of the mob, however, and was beheaded in Cheapside, with his body thrown on a dungheap “to be torn and devoured by dogs”. It was later reburied by his supporters beside his grand abode.

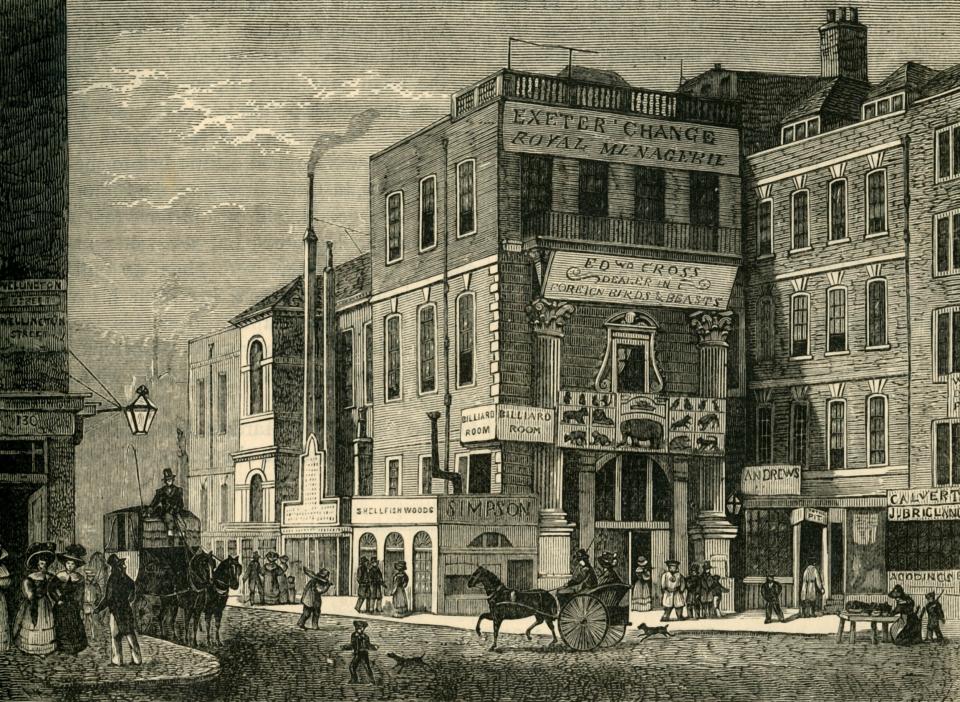

A second Exeter House, also known as Burghley House, emerged in the 16th century – but on the north side of The Strand. Built for William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley (who dubbed it his “rude new cottage”) it had three storeys with four-storey corner turrets and a garden big enough for a paved tennis court, a bowling alley and an orchard. Cottage indeed. It was converted into the Exeter Exchange in 1676, best known for the menagerie that occupied its upper floors for over 50 years. Lions, tigers and monkeys, among other exotic beasts, were kept for the entertainment of Londoners – the roars of the big cats could be heard from the street. When the building was demolished in 1829, the animals were transferred to the new London Zoo.

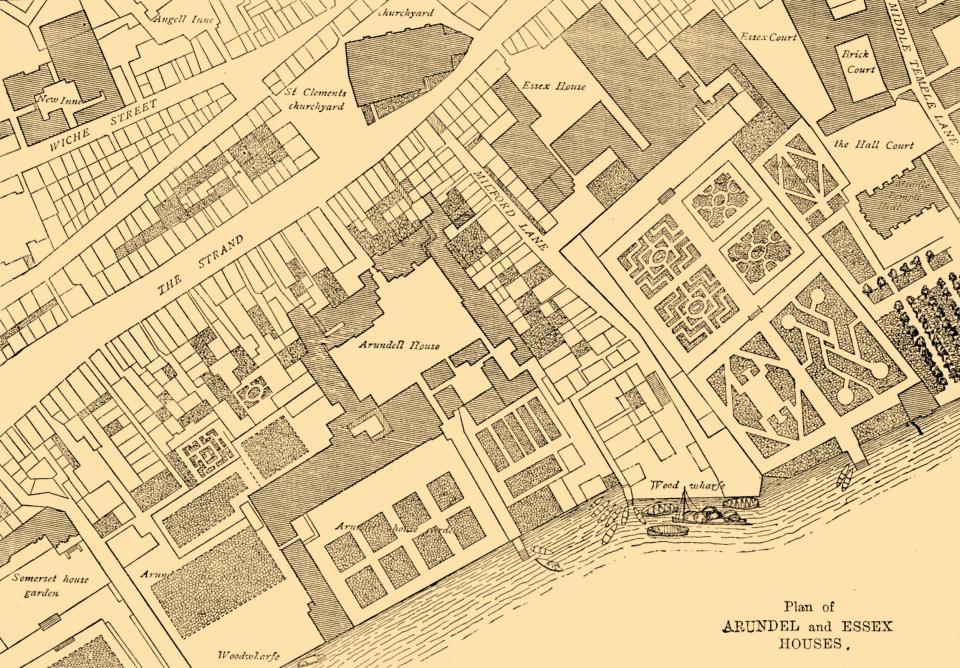

Essex House

The original Exeter House, facing the river, was replaced by Essex House, built around 1575 for Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester (and originally called Leicester House) and renamed after being inherited by Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex. Still with us?

“Large but ugly,” was Pepys’ assessment, but with 42 bedrooms, a picture gallery, kitchens, outhouses, a banqueting suite and a chapel, you wouldn’t catch many other Londoners turning their nose up.

The house was demolished in the 1670s; 21st-century Essex Street, beside Middle Temple, remembers it.

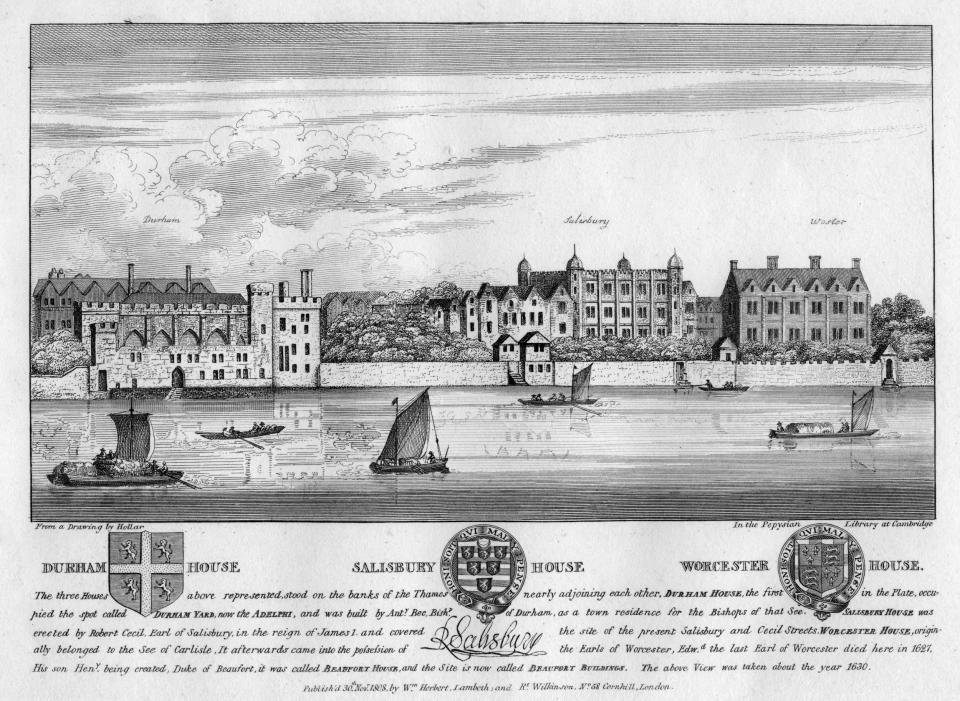

Worcester House

Next up, travelling west, was a mansion for the bishops of Chester and Coventry, followed by Worcester House, originally built for Carlisle’s clergy (and called Carlisle House) but handed to the Earls of Worcester under Henry VIII.

Its gardens extended right to the water’s edge. The historian John Stow records that there was “a very large walnut-tree growing in the garden, which much obstructed the eastern prospect of Salisbury House, near adjoining. It was proposed to the Earl of Worcester’s gardener, by the Earl of Salisbury or his agent, that if he could prevail with his lord to cut down the said tree, he should have £100. The offer was told to the Earl of Worcester, who ordered him to do it and to take the £100; both of which were performed to the great satisfaction of the Earl of Salisbury, as he thought; but, there being no great kindness between the two earls, the Earl of Worcester soon caused to be built in the place of the walnut-tree a large house of brick, which took away all his prospect.”

Worcester House became Beaufort House in the 17th century but was torn down soon after.

Arundel House

During the medieval period, the next plot was taken by Bath Inn, the townhouse of the (baby-eating?) Bishops of Bath and Wells. Henry VIII nabbed it for his cronies in 1539 – first William Fitzwilliam, Earl of Southampton and then Thomas Seymour. Alas, Seymour lost his head for treason in 1549 and it was sold for a bargain price of £40 (about £22,345 in 2024) to Henry Fitz Alan, 19th Earl of Arundel.

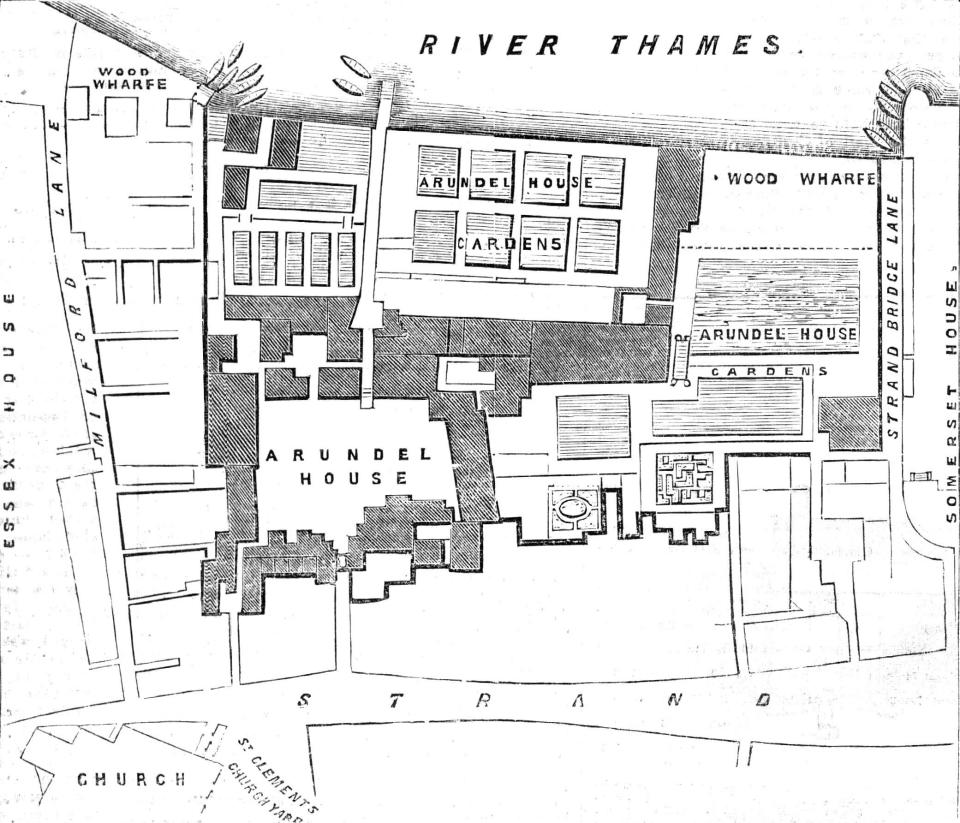

A new entrance gateway designed by Inigo Jones was added, and in the 17th century Arundel House was packed to the rafters with art, including an impressive haul of Old Masters and the Arundel marbles, a collection of ancient Greek sculptures now held by the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford (barring one 2nd-century relief from Ephesus which is at the Museum of London). At its greatest extent there were a reported 37 statues, 128 busts and 250 inscriptions, as well as a large number of sarcophagi, altars and fragments. Pepys visited in 1661 and described “fine flowers in his garden, and all the fine statues in the gallery... and thence to a blind dark cellar, where we had two bottles of good ale.”

The house was demolished between 1680 and 1682. Today, Arundel Street links the Strand with Temple Place, as well as statues of two lookalike liberals: Gladstone and John Stuart Mill. Look out too for Milford Lane, described at the start of this article in an excerpt from John Gay’s poem Trivia. The Arundel House of the 21st century is a conference centre.

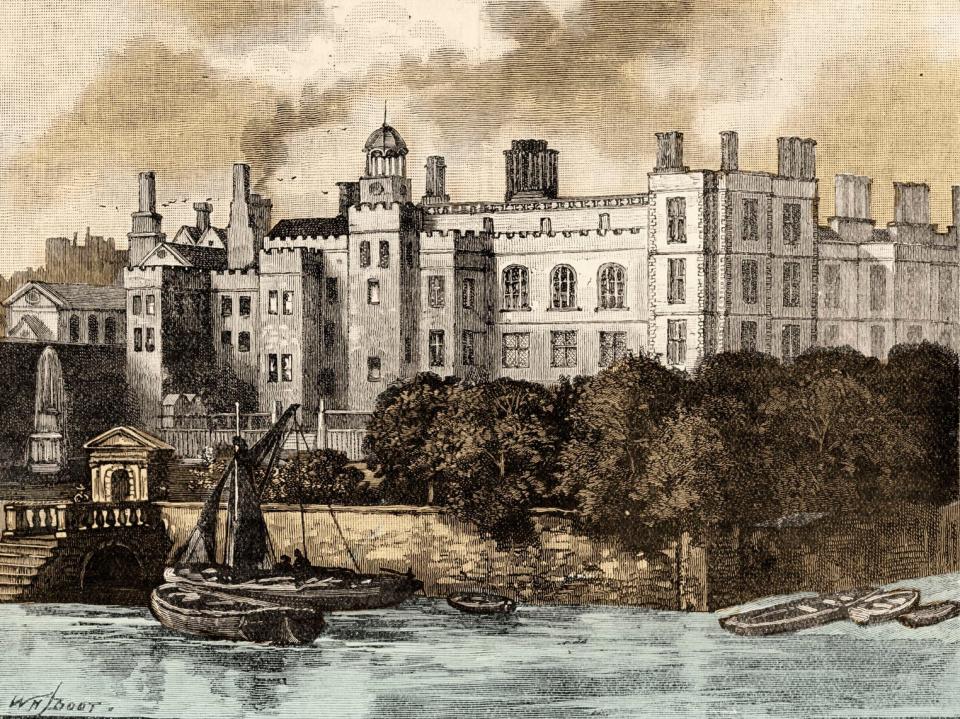

Somerset House

Next up is the sole survivor: Somerset House. The current version, however, wasn’t built until the end of the 18th century. Old Somerset House was built by Edward Seymour from around 1549 to celebrate becoming Duke of Somerset and Lord Protector. It had two storeys, with a three-storey gateway and a large quadrangle. Unfortunately for poor Seymour he upset the wrong people and was executed at Tower Hill on charges including “ambition”, “vainglory” and “following his own opinion” before his grand house had even been finished.

After passing into the possession of the Crown, the future Elizabeth I lived there during the reign of her sister; it later became the residence of James I’s wife, Anne of Denmark, and was renamed Denmark House.

During the English Civil War it was seized by Parliament, the contents sold for £118,000 (almost £20m today), and became General Fairfax’s army headquarters. Inigo Jones died at Somerset House in 1652, and Oliver Cromwell’s body lay in state there after his death in 1658.

Following the Restoration, royalty returned. The wife of Charles II, Catherine of Braganza, lived there for a time; Edmund Berry Godfrey, whose mysterious death in 1678 caused anti-Catholic uproar in England, was reputed to have been murdered in the property’s courtyard (he was later found face down in a ditch on Primrose Hill, impaled on his own sword).

Modern Somerset House was built to house the Royal Academy, the Royal Society and the Society of Antiquaries. Art remains today (the Courtauld Gallery is found there), while it serves as an HQ for various creative and cultural institutions. The central courtyard offers film screenings in summer and ice skating in winter.

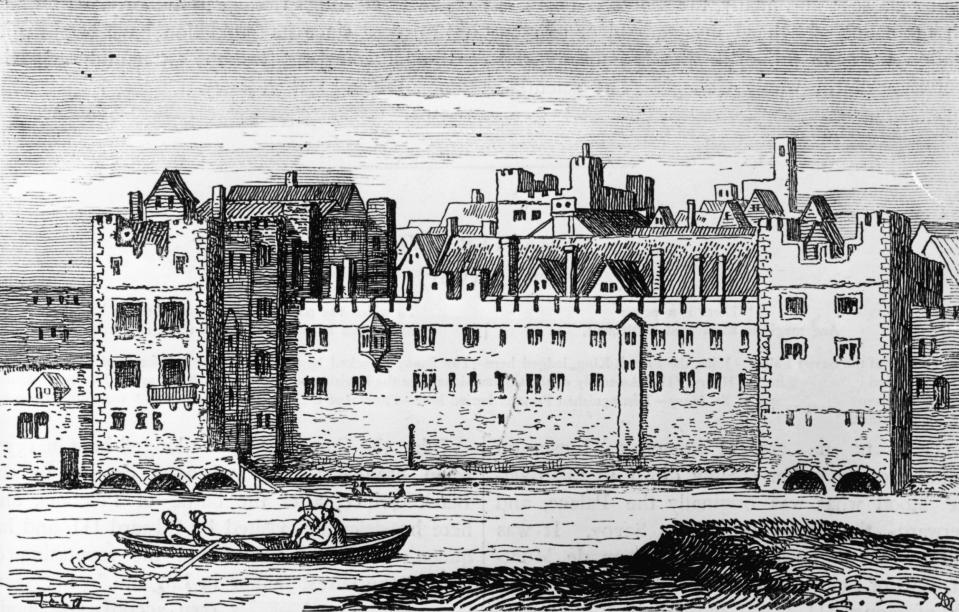

Savoy Palace

To the west of Somerset House once stood Savoy Palace, one of the most imposing of all the Strand’s mansions. The fortress-like former home of John of Gaunt, it was rebuilt between 1345 and 1370 at a cost of £35,000 – something like £46m today. That sort of cash could afford one a mansion “unto which there was none in the realm to be compared in beauty and stateliness”, according to John Stow. It had a library, chapel, cloister, fish ponds, orchards and a vegetable garden.

It 1381, however, it was razed during the Peasants’ Revolt. Wat Tyler’s followers did away with the guards, stormed the courtyard and broke into the treasury. They didn’t pocket the cash, however. Instead they crushed the precious gems they found with hammers, tossed coins into the Thames, and threw fine furs, silks and tapestries onto an enormous bonfire in the Great Hall. A barrel, thought to hold gold but actually filled with gunpowder, was then cast onto the flames, bringing down the roof and setting alight to the rest of the mansion.

“Tyler and his men were serious rebels intent on making serious points rather than plundering for plundering’s sake,” explains Dr Matthew Green. “One peasant caught stealing was cast into the flames like all the other tokens of gluttony.

“But not all the rebels were able to meet the high standards of parsimony demanded of them by their leaders. A breakaway platoon of peasants headed for the Savoy’s cellars. The aim, ostensibly, was to take an axe to the duke’s barrels of fine wines but instead they themselves got drunk. When the roof collapsed, trapping them in the cellars, they did what any reasonable person would have done: drank the rest of the wine. Seven days later, they were dead.”

The Savoy name stuck. Henry VII founded the Savoy Hospital on the site in 1512 (only a chapel remains today) and today’s travellers will find the Savoy Hotel and the Savoy Theatre.

Durham House

The Bishop of Durham’s London crash-pad came next, boasting a large chapel, great hall supported by marble pillars and ample courtyard.

Henry VIII pinched it, of course, and Anne Boleyn lived there in 1532 while the king courted her. It was later given to his daughter Elizabeth. The nine-day queen, Lady Jane Grey, was married there in 1553.

Elizabeth later granted it to Sir Walter Raleigh and two of the property’s most curious guests were Manteo and Wanchese, Native Americans brought back to England by early settlers in Virginia. Raleigh oversaw the first expeditions to Roanoke and explorers were able to persuade “two of the savages, being lustie men, whose names were Wanchese and Manteo” to accompany them on the journey back to London, whence they caused a sensation at the royal court (and were assigned digs at Durham House).

The Bishop of Durham reclaimed the building after Raleigh’s downfall but didn’t live there and it slowly fell into ruin. The last fragments were cleared away during the reign of George III.

Cecil House

The powerful Cecil family occupied the next plot, where today you’ll find an Art Deco masterpiece, Shell Mex House, the former London headquarters of Shell-Mex and BP.

Long after they moved out, one of London’s most luxurious hotels moved in. Hotel Cecil opened in 1896, three years before the nearby Savoy, and stretched from the Strand to the Thames. It had 800 spacious rooms – a staggering number when one considers that the Savoy today has just 268. Public areas included a bright and airy courtyard, a vast Palm Court ballroom (perfect for afternoon tea during the day and dancing at night) and three restaurants capable of feeding a total of 1,150 diners. There were terraces to lounge in – and even a beauty salon. Rates in 1907 ranged from five shillings for a single room (“including light and attendance”) to 25 shillings for a suite – that equates to around £600 today. Breakfast was an extra two and six.

One of the best contemporary descriptions can be found in Nathaniel Newnham-Davis’s 1914 book, The Gourmet’s Guide to London. He explains how the bustling courtyard at the Hotel Cecil’s entrance, known as “The Beach”, was a popular hangout for American guests who preferred it to the gilded parlours within. “The most American spot in London” was filled with cane chairs, piles of luggage, a newspaper stall, and “in the summer-time pretty girls sunning themselves and waiters hurrying to and fro with cold drinks and long straws”.

For the full story of the Hotel Cecil, which was demolished in 1930, follow this link.

York House

Our penultimate stop is York House, built as the London home of the bishops of Norwich (and called Norwich House, obviously), granted to the Archbishop of York in 1556, and then leased to various Lord Keepers of the Great Seal of England, including Nicholas Bacon, Thomas Egerton and Francis Bacon.

George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham, acquired it in the 1620s. Under his watchful eye York Watergate, the only surviving fragment of the stately home, was built as a grand Italianate riverside entrance. It is now marooned 150 years from the water thanks to the construction of the Thames Embankment. An inventory of the property’s contents in 1635 revealed that the interior was just as ostentatious, with 22 paintings, 59 pieces of Roman sculpture, and 31 other heads and statues listed.

Northumberland House

Last but not least was Northumberland House, which occupied the western end of the Strand from 1605 until 1874. Fifty metres wide, with a great hall, central courtyard and turrets on every corner, it was at first occupied by Henry Howard, 1st Earl of Northampton, before passing to the Earls of Suffolk, then the Percy family, who were the Earls and later Dukes of Northumberland.

Two 30-metre wings were added in the 18th century containing a ballroom and a picture gallery housing works by Titian, da Vinci and van Dyck. The Glass Drawing Room was celebrated as one of London’s finest interiors (surviving wall fittings are in the collection of the V&A). By this time, however, most of London’s wealthy families had moved west to Mayfair, leaving Northumberland House rather isolated in a neighbourhood of small shops.

It was knocked down in an act of vandalism in 1874 so a road could be built from Charing Cross to Victoria Embankment.