Leila Slimani's New Book Reckons With Sex in the Arab World

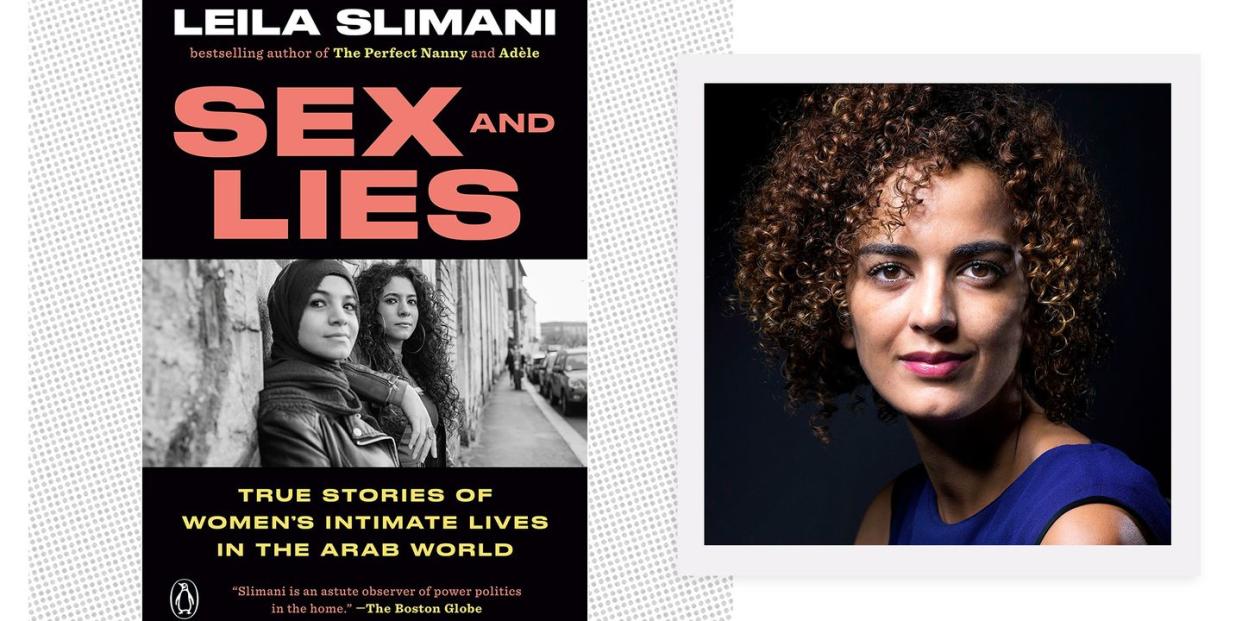

Moroccan-born, Paris-based author Le?la Slimani uses writing to take the cultural temperature. Her first novel (published in English as Adèle) examined sexual addiction in a twist on the Dominique Strauss-Kahn debacle. Her follow-up, The Perfect Nanny, unpacked social hierarchies and was inspired by the true story of a caregiver who killed her young charges. It was a widely translated bestseller and won the prestigious Prix Goncourt in 2016.

Slimani’s latest work, Sex and Lies: True Stories Of Women's Intimate Lives in The Arab World—published in 2017 in France and translated into English this year with a new preface—compiles firsthand accounts of repressed desires and forced discretions, collected while on a Moroccan book tour in 2015. Slimani relays the stories alongside her own impassioned commentary: a call-to-arms for legal reform in Morocco and a reset of antiquated, misogynist values that drive people to dangerous duplicity. One of the women interviewed, a doctor and theology researcher, summed up the situation thusly: “We are fed a zealot’s diet of Islamic discourse of what’s halal and what’s haram and which, while claiming to cover women up, manages to effectively hyper-sexualize them.”

Morocco’s punitive laws regarding virginity (Article 490), marriage (Article 491), heteronormativity (Article 489), and abortion (Article 449) are anchored in traditions that don’t match modern-day conduct and relationships. The laws act in service of a “morality that’s both penny-pinching and vague,” Slimani states, and are upheld arbitrarily. “People are sick of the injunction to lie about their private lives,” she writes, which only “engenders violence and confusion, inconsistency and intolerance.”

In the book, out in the U.S. today, Slimani thoroughly explores the ambivalence of North African countries to confront these issues. Below, she discusses the socialization of shame, the new wave of ambition young women, and how her anger prevents her from ever feeling defeated.

Throughout the book, people note that the topics once considered taboo in Morocco have very gradually shifted, over the last few years. But you’re calling for radical, immediate change. What could effectively rupture the dominant traditionalist thinking?

Right now, the most important thing is to change the laws. It would be a utopia to think, "First we wait for society to be ready for this change"—I don't believe that. We need first to change the law and then society will accept the situation. Because right now it is an emergency. Every day there are 600 abortions—illegal, of course. There are so many rapes—within marriages, of young girls who don't dare go to the police because they are in fact more afraid of their own families and how people are going to look at them.

Can you talk about the manifesto you created in September 2019, precisely trying to facilitate legal reform? You also started the @morroccan.outlaws.490 Instagram account.

When the journalist Hajar Raissouni was arrested at a clinic, along with the medical staff tending to her, it was a huge scandal in Morocco. A lot of people defended her. My friend Sonia Terrab, a director and writer, and I decided it was important to shed light on the hypocrisy of Moroccan society, and even more so on the Moroccan government. This is the paradox—it is impossible to apply these laws. Because they know that we are all outlaws. We have sexual intercourse while not being married. We have abortions.

When we published the manifesto, we were surprised by how successful it was; we got responses from all over. The Moroccan constitution gives us the opportunity, once we have 15,000 signatures, to propose a change of the law to parliament. That’s exactly what we did. Now, with the virus, the parliament is closed; but when everything starts up again, we can continue to fight.

?? Send us your story anonymously using the link in bio ? #moroccanoutlaws #article490

A post shared by Moroccan outlaws (@moroccan.outlaws.490) on Jun 30, 2020 at 5:52am PDT

Legal structures need to change, but so does the microcosm of the family. There’s a compelling line about this: “Stop telling your daughter she’s a target, stop telling your son he’s a hunter.” How can change happen within the family unit?

What makes me optimistic right now is that the best students in Morocco are young women. I spoke with many, and they all tell me the only solution—the only way to be emancipated—is by studying. The truth is a lot of parents, especially fathers, are very proud of their daughters; more than of their sons. Boys can go out, but the girls are at home studying. If they become doctors or lawyers, it’s upward social mobility that reflects well on the family. I think this generation of women is going to change a lot of things; they are going to educate their own daughters in very different ways than how they were educated themselves.

While this book is very tied to the North African region, the problems of power and gender it addresses often transcend place. Do you find these themes resonate in similar ways everywhere, or are they received differently in different contexts?

What is interesting is that in France, for example, people have said to me: "Oh, but I love Morocco! I go there on holidays… Moroccans are so nice at the hotels I go to," or some kind of ridiculous comment.

Oh my god.

[Laughs] I think through cinema and literature, you have more and more stories about North African women, and how they fight to gain a place in society. That’s what I’m trying, also, to do with this book. I didn't just want to say: "Moroccan women are suffering." No. I wanted to say: "We want to change the situation. We are fighting every day, and we try to find ways to love, to make love, to have children or not have children."

People were impressed by the women in the book, by their strength. Many are anonymous—but some of them gave their real names, and that’s a risk.

You place sexual deprivation within a wider context of social deprivation. Can you talk about this interconnectivity?

For one, there is the concept of hshouma, the idea of honor. Women have to assume the burden of hshouma all the time, ever since they’re little girls. Women grow up with this idea that any mistake she makes will have terrible consequences not only on herself but on her family and in the eyes of the neighborhood. There is this idea that you are responsible for everyone. You don't have the right to intimacy or privacy. But I think that is something very important for women: to have the right to have secrets. A woman is thought to be a mother or a wife, full of love and sacrifice for others. But it’s important to be able to say: you don't know everything about me. I have a secret mind.

In the book, you use the phrase “sexual citizenship”—meaning that to fully participate as an individual in society, one must be comfortably embodied on their own terms.

Exactly. When you are humiliated in your body, and people want the right to know who you’re having sex with and where; you feel you have no place in society. It’s very, very violent.

I also think the big problem is that we don't consider sex in terms of consent. The question around sex is not "did you consent?" but "are you married?"—and if you’re not, you go to jail. Sex should only be illegal based on consent. The rest does not matter.

Despite the discouraging status quo, you have a hopeful outlook. How do you maintain it when society seems so resistant to change?

You can't fight if you don't have hope. I’m optimistic by conviction—I force myself to be optimistic. I don't want to accept what the Islamists and especially the terrorists are trying to do. They want you to be afraid, to be hopeless, to think that nothing can change. I would never accept that. Never. For me, it’s something very subversive. It’s like a violence towards them, to tell them, "I think we will win and I think things will change." I can't imagine that women will not have this freedom. It feels so important to me. Of course I’m full of hope.

You Might Also Like