Last February, Jerika Binks Went for a Run. No One Has Heard From Her Since

In hindsight, the weather seems like a metaphor. It was 52 degrees in American Fork, Utah-oddly warm for February, when temperatures typically drop below freezing. Jerika Binks, 24, seized the opportunity to go for a run, the early spark of spring offering her a chance to log some serious miles-she regularly ran 15 or more at a time. But off in the distance, a storm was brewing. A gray haze of snow clouds formed over the Wasatch Mountains, looming above the city from the East. By nightfall, a blizzard would white-out the town and Jerika Binks would be a missing person.

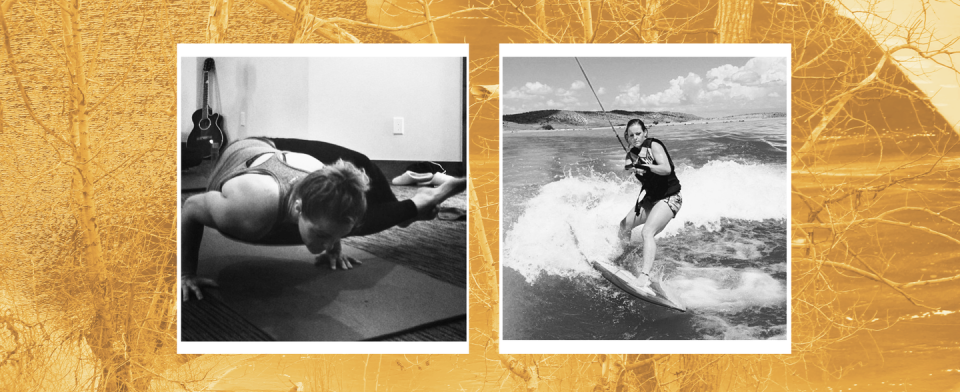

She had actually been planning to run that day with her roommate. But it was Sunday, February 18, and the roommate decided to go to church instead. This was not a deal-breaker for Binks, a natural athlete who loved the outdoors and frequently ran alone. Running was her religion. She also took self-defense classes and went duck hunting with her 20-year-old brother, Porter. She dreamed of opening her own gym someday. Her mom, Suzanne Westring, describes her as “pure muscle.”

Around 9 a.m., Binks put on her new running shoes-the so-called “barefoot” kind that look like gloves for toes-and put on a pair of dark green leggings and a two-toned gray hoodie. Leaving her wallet and ID at home, she grabbed her phone, water bottle, and earbuds. She often listened to country music to set her pace, but had lately been obsessed with a Pandora pop workout station suggested by her sister, Sydney, 22.

Binks didn’t use a tracker-no Apple Watch or MapMyRun app. But shortly before 9:30 a.m., she turned left onto North Country Boulevard, a busy street lined with chains like McDonald’s, Chase Bank, and Dollar Tree, in addition to ranch-style houses. Surveillance footage charted her path past the Mormon temple, where bridal parties gather for pictures in the garden outside and patches of lollipop-colored tulips sprout in the spring.

At 9:38 a.m., she was recorded jogging at a steady pace past the Utah State Developmental Center, a state agency that provides support to people with disabilities, and at 9:50 a.m., past Wal-Mart-the place where she bought her groceries, including peanut butter, bananas, and high-fat foods like tuna (she'd been thinking of going keto). From there she headed East towards the snow-capped mountains, and American Fork Canyon, a wooded paradise of trails popular with hikers and rock climbers.

At this point she was clocking a pace of just under nine minutes per mile, according to surveillance video timestamps. She reached the entrance to the Highland Trail at 9:55 a.m. This route would wind her through scenic parts of the canyon, a haven for moose, bald eagles, and mountain goats, where the fir trees are fit for Christmas and families wade in a glassy reservoir in summer. This was supposed to be the peaceful part of her run. But there’s no evidence Binks ever made it out.

Running is increasingly popular among women. They comprised over half of road-race participants in 2017, versus previous years when men made up almost 70 percent of competitors, according to Running USA. But women also feel increasingly unsafe while running. Disturbingly, in one Runner’s World survey from 2016, one-third of female joggers reported having been followed by someone in a vehicle, on a bicycle, or by foot, while out for a run; nearly half reported experiencing some form of harassment.

Meanwhile stories of women being attacked while running have lately dominated the news: In July of this year, Mollie Tibbets, 20, went missing in Brooklyn, Iowa. A suspect was identified after his car was seen driving back and forth in the area on surveillance cameras; he told police he'd followed Tibbets and ultimately parked and run alongside her. When she rejected his advances, he became angry and blacked out, he says; he later found her in his trunk.

Two months later, Wendy Martinez, 35, a chief-of-staff at a tech start-up, was brutally stabbed while running in Washington D.C. In 2016, there was Alexandra Brueger, 31, a nurse shot four times in the back during her normal 10-mile jog outside Detroit, Michigan (her case is still unsolved); Vanessa Marcotte, 27, a manager at Google, found dead, naked, and burned after going for a run near her mom’s home in Princeton, Massachusetts (a father of three is currently awaiting trial after DNA evidence linked him to the scene); and Karina Vetrano, 30, a speech pathologist for autistic children and was strangled, sexually assaulted, and killed while out for a run in Queens, New York (a suspect is awaiting retrial after a mistrial).

In 2017, Kelly Herron, 36, successfully fought off an attacker in a public restroom in Seattle during a mid-run bathroom break (she later launched the site Not Today Motherf@#!er to encourage women to learn self-defense); in October of this year, Maria Ball, 26, screamed so loud when attacked during a 16-mile training run for the New York City marathon that her potential rapist fled; and this past June, an anonymous woman in Massachusetts escaped a man who was attempting to force her into his car as she jogged around her neighborhood.

No wonder 73 percent of women say they will only run if they have their phone with them, and 60 percent will only run in daylight, according to the Runner’s World survey. And that brands have rushed to create products to help women protect themselves: GoGuarded makes a $14 ring that doubles as a sharp weapon; for the same price, Kuba-Kickz makes spikes that can be used to kick an attacker in the shins. Sabre introduced a $22 runner-friendly pepper spray.

Binks didn’t have any of these things, though. American Fork is the place where she had lived for over a decade, graduating high school with a trade certificate qualifying her to become a medical assistant. It's a place where a common newspaper headline reads, “Utah Valley University Continues Its Jazz Jam Series.” Binks had run in this town countless times, past apple trees and waving walkers, and up into the canyon trails, similar to ones she'd grown up navigating with her mom and siblings. Maybe that’s why she wasn’t wearing a ring that doubled as a weapon. Instead, she wore a green-stone band that she'd bought with Sydney at the mall-it was the only thing missing from her jewelry box.

That February, Binks’s life had been looking up. When she left for her run, it was from the voluntary sober-living facility where she'd been staying for four months, since October. She had struggled with drug addiction in the past, but her family says she was clean and committed to rebuilding her life. “We had a very open and honest relationship,” explains her mom, Suzanne. “I know she was doing well, spiritually, mentally, physically.” Searches of her cell phone records proved she hadn't been in contact with anyone from her old days. She had just started a new office job at a construction company, and saved up for a little black Mazda. Binks had even made plans to go car shopping with her mom and 28-year-old big brother, Jed, later in the week. She was also looking forward to a spiritual day-trip she’d booked for late February to a sweat lodge.

When she didn’t return to the sober-living facility on February 18, an employee called Binks’s mom, who lived nearby, to let her know. Westring was immediately worried. A search of her daughter’s room turned up all of her belongings, including two uncashed checks on her desk, along with her wallet and ID. Calls to her phone went immediately to voicemail. Something wasn’t right.

Westring reported Binks missing the same day. But as darkness fell, so too did the snow, furiously, piling up over a foot as the temperature dropped. Car accidents-217 over 12 hours-tied up all the emergency responders in the area. Conditions were slippery in the canyon, making a search for Binks impossible. To make matters worse, the missing persons report had been filed in the wrong district due to a police error, resulting in bureaucratic red tape instead of immediate action. “We lost really crucial time in the beginning,” Westring says. When search crews finally set out to look for Binks, eight days had passed.

The crews focused at first on preliminary cellphone pings from Binks’s phone: one recorded at 10:30 a.m. at the opening of American Fork Canyon, and another at 1:30 p.m., from a tower in Saratoga Springs 10 miles away. These efforts proved to be misplaced. Three weeks later when more accurate cell phone data was obtained, it showed that searchers had been focused on the wrong area (pings don’t always go to the closet tower). They refocused their search to the canyon ever since.

Brittany Lisenby, a 31-year-old photographer who had been hiking in the canyon with her boyfriend and dogs the day Binks went missing, reported to police that she heard gunshots that day. “It wasn’t hunting season, and it sounded more like a hand gun than a rifle,” she told Cosmopolitan. The noise freaked out her dogs. And she had already been feeling jittery after passing a camp that “looked like someone had done some sort of ritual there,” she says. She’d seen sticks sharpened into spears placed into symbols along the ground. But shockingly, Lisenby’s tip didn’t result in any concrete leads. For a while she became obsessed with reaching out to anyone who had posted on Instagram from the canyon on February 18. Did you hear the gunshots, too? Did you see anything suspicious? These days, she refuses to go hiking without her dogs.

Weeks went by and nothing. Binks’s uncle, Paul Conover, started going door-to-door along her running route to see if anyone had seen anything or had any video footage that might contain a clue. Desperate to keep momentum going, the family offered a $5,000 reward for any information about Binks’s disappearance.

On March 28, as the snow melted into Little Cottonwood Creek, a break seemed to emerge in the case: wildlife camera footage retrieved by park staff in the canyon showed a woman running down the Timpanogos Cave Trail at 1:30 p.m., in an area of the park that was closed for the winter. Binks would have been outside for four hours by that point, which was not unusual for her. She was heading towards the road, and the canyon's exit. Pictured only from the back, at close range, she is wearing dark green leggings and a gray two-toned hoodie, her brown ponytail bouncing.

Police combed the area thoroughly. “We searched that trail three or four times for days with search and rescue, planes, helicopters, and drones,” said Detective Pratt of the Utah Sheriff’s Office. “We went down the shoots, across ledges, we went everywhere a person could go.” Searchers repelled down cliffs; dogs searched for her scent on well-worn trails and in more remote spots. The family searched on their own, too. “We organized four primary searches and multiple small searches, and many volunteer drone flights,” Conover said. (They continue to review weeks of drone footage with the help of technology provided by the Wings of Mercy, a volunteer group that analyzes drone footage for the families of missing persons.) No one found anything-none of Binks’s clothing, no water bottle, no trace of her at all.

“Something was very wrong, terribly horribly wrong,” Westring said. “I felt it as a mother.” But what happened?

Theories started to develop. Could Binks have been attacked by a mountain lion? It’s possible. The animals have been spotted in the area, and they’re known to drag their victims out of sight, which could help explain the lack of evidence. But mountain lions typically hunt in the morning and evening, not in the middle of the afternoon, and attacks on humans are rare. “We’ve never had a person killed by a mountain lion in the state of Utah,” said David Stoner, Ph.D., a researcher at the Utah State University Department of Wildland Resources.

Could she have slipped and fallen in a remote spot of the canyon? It is possible she ventured into some tricky areas. But then how to explain the 1:30 p.m. photo that shows her on a well-maintained trail just half a mile away from the entrance to the park? It seems unlikely that just as she was about to exit the park after four hours of exercise, she turned around and ventured back up into dangerous territory. And even if she had, wouldn’t a drone, a helicopter, a foot search have found her? Other hikers have gone missing in the canyon and they’ve been found.

Had she run away? Binks had expressed interest in leaving the state earlier that year, and she loved the ocean. But her sober-living facility was voluntary-it’s not like anyone was keeping her there. And wouldn’t she have cashed the checks she left on her desk or grabbed her wallet? Or at least waited until the snowstorm passed, and she had bought that little black Mazda? Instead, her bank account sat unused, with thousands of dollars in it. Nearly a year later, there has still been no activity.

In the wake of depressingly regular attacks on female runners-Mollie Tibbets, Wendy Martinez, Alexandra Brueger-it’s hard not to consider the darkest option: someone attacked her that day.

This is the theory that Westring chooses to believe. “Foul play is the only reason Jerika didn’t return from her run,” she says with certainty. “I know that.” Detective Pratt admits that abduction hasn’t been ruled out.

Runners are more vulnerable than other athletes. Some carry pepper spray, but most lack a way to defend themselves, while hikers often have knives or poles and cyclists can move faster.

Some experts say that the current focus on running is misguided-and that the attention these cases attract distorts the real threat to women, which is violence committed by men they know. A report by the United Nations this year revealed that domestic violence is the most common killer of women around the world. “It’s not that violence against runners isn’t a major issue-women are being murdered-but the truth is, there aren’t any spaces that are completely safe for women,” says Callie Marie Rennison, PhD, a professor and director of equity at the University of Colorado. “You stay home, and that’s where most violence happens. Then you go for a run, and you can’t stop thinking about the women who have been murdered, attacked, and harassed.” (Police interviewed men who had been connected to Jerika in some way and did not find any suspects.)

Westring never would have imagined that running would be dangerous for Binks-it was her happy place, the meditative constant in her life and a key agent of her recovery. Running was how she took care of herself. It wasn’t supposed to be the thing that caused her harm.

It’s been almost a year now, but Westring hasn’t stopped looking for her daughter. She worries that Binks’s previous issues with drugs caused some people to write off her case, or for interest to wane. “Because she had gone through some problems before, some of the media coverage made it seem like maybe she had run away,” Westring said. “Kind of manipulating the story into saying that she left most of her belongings. No. If she wanted to move, she would tell me.”

The night before disappeared, she had gone bowling with her roommates and called her mom when she got home. There was not an inkling of anything wrong in her voice.

And Binks was close to her family-she dyed Sydney’s hair, was Porter’s biggest fan, counted her mom as her best friend. She wouldn’t have left them, they all agree.

So Westring searches the canyon weekly, aimlessly wandering through trails and paths looking for something. A shoe, a clue, a sign. She approaches random strangers to talk about the case. Could they be the ones who share the small detail that leads to a big break? Park workers at the ticket booth recognize her burgundy car and waive the $6 entrance fee. She continues to email running groups, hoping that maybe someone's memory will be jogged or they’ll have come across a runner in the canyon who saw something that day.

The family also created a Facebook page to spread awareness and made videos of Binks laughing and smiling in hopes that people will share them on social media. The dream is that they’ll go viral and lead to her return. In the meantime a Utah advertising agency donated a billboard along the local interstate reminding the public to call if they have info about Binks’s case. Detective Pratt says the case is still open, but until something new presents itself, police aren’t actively searching for Binks. They currently have no suspects.

One day in October, I decided to set out on the same route Binks ran. I wanted to see what she might have seen, to feel how she might have felt.

I start by sprinting north on North Country Boulevard. When a car slows down alongside me, my muscles reflexively go tense. I am aware that just like Binks, I am a woman running alone-brown hair, 120 pounds. But when I look up, the driver sends me through the intersection with a friendly wave.

Did Binks’s killer pull up in a car, just like this one? Did she exit the park and head for home, and after four hours, was she just too tired to fight him off? I run past the Mormon temple, the one where people take pictures-today, there are tulips-and also by the Wal-Mart. The canyon looms, large enough to blot out pieces of the sky. There are fall leaves sprinkling the path in front of me. They are beautiful. They are also unsettling, because they represent another season Binks is gone.

All around me, I see a normal suburban tableau, of people, cars, chain stores, turning right and left, coming and going. But I cannot outrun the reality that women like me have been murdered for doing this very thing. I am trapped by fear even as I propel my body forward. My nerves are firing. Did he come from behind and grab her? Did anyone even notice? I walk through the canyon and wonder,Was this the part of the trail where it happened? Was the wind blowing that day, too, just slightly? Did it carry away her screams?

Don’t run alone, Binks’s mom had told me. I did, and I will continue to, because I am a runner, and that’s what we do. But I’ll always be looking over my shoulder now, worrying, wondering. That’s what we do now, too.

If you have any information about Jerika’s disappearance, please call Detective Pratt at the Utah County Sheriff's Office: 801-851-4013. No detail is too small.

('You Might Also Like',)