I was kidnapped and raped at 14. Then 25 years on, I confronted my attacker

On a cold evening in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1978, 14-year-old Debora Harding was walking to school for late choir practice, which she soon found out was cancelled because of the weather. She was on her own and ill-prepared for what was turning into an ice storm – the zip of her coat was broken and she had no hat or gloves.

Meanwhile, Charles Goodwin, 17, was waiting in the school parking lot to pick up his cousin. He had been released from a young offenders’ institute only 10 days earlier and was in a stolen van – he was an inveterate carjacker. But he was broke. And at some point, it occurred to him that kidnapping might be a good option. He had a ski mask and he had a knife. And minutes later, he had a victim.

He jumped from his van, held the knife to Harding’s throat and shoved her into the footwell of the passenger seat. For the next couple of hours, under very challenging circumstances, she managed to stay calm; when he noticed she was wearing a cross, they talked about God and discussed how much money her dad might give him in order to get her back.

But the mood changed. Goodwin manhandled her into a pay-phone booth and, with the knife still at her throat, made her call her father and tell him to bring $10,000 to a parking garage that evening or he would kill her. At first her father thought she was playing a trick on him, but he agreed. Goodwin put a burlap bag over Harding’s head, tied her hands, shoved her back in the car and drove her to a remote place. Then he made her get out of the van and he raped her.

She lost her religion that night – literally, the little cross she had been fingering for comfort came off in the back of the van. Goodwin left her in some cattle stockyards and told her he was going to pick up the money, and then come back for her. She was outside, her hands still tied, with a bag over her head and she was terrified. If she moved, the coat would fall off her shoulders and the temperature was minus six degrees.

‘I was 14 and I had no experience of sex, I didn’t know what had happened to me,’ Harding tells me. ‘I didn’t know what way I’d been violated until I got the hospital report many years later. What I mainly remember from that night was standing in the freezing cold screaming at God and trying to work out how I was going to get out of this situation, and if I would live or die.’

She was scared that Goodwin would kill her father and, spurred on by this, she managed to get the burlap bag off by scraping her forehead against the wall. She inched forward across the ice, until she saw a woman coming out of a trailer office. The woman called the police and the three-and-a-half-hour ordeal was over.

Goodwin, meanwhile, went to the appointed meeting place, realised the police were there– called by Harding’s father – and went home. Eight days later, he was arrested. The evidence was irrefutable, he pleaded guilty to kidnapping and first-degree assault and was sentenced to 12 to 20 years in jail.

Debora Harding has a soft American accent, a warm, welcoming manner and a purposeful stride. Since 2011 she has lived in a Hampshire village with her husband, the writer Thomas Harding, and their daughter Sam, 21, who is studying history and politics at Cambridge.

I am here to talk about her book, Dancing with the Octopus: The Telling of a True Crime – a superb literary memoir of violence and its consequences. She marches me down to the lovely village pub, and it is in this idyllic setting, surrounded by cornflowers, roses and daisies, and dive-bombed by robins and blackbirds, that we sit in the sun and talk about rape, kidnap, abuse, suicide and tragedy.

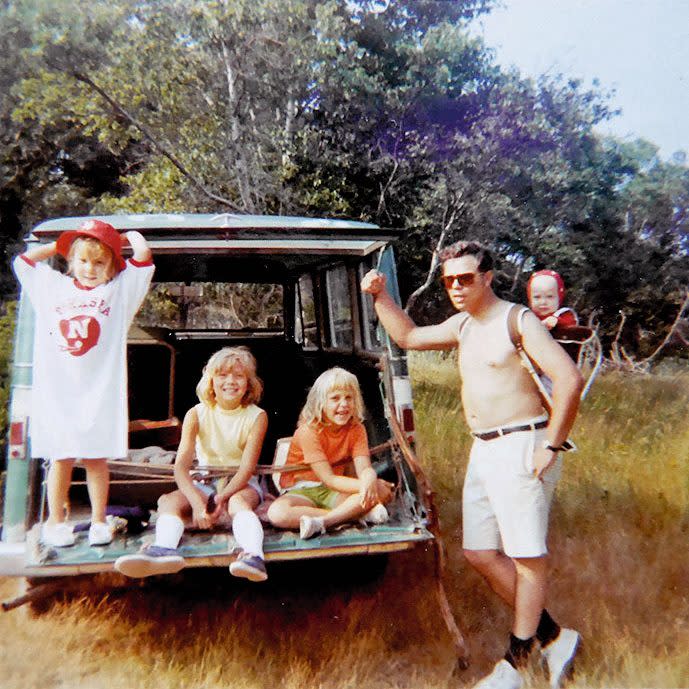

Debora was the second of four girls. When she was five, the family moved to Lee Valley, Omaha, and she and her sisters - Genie, Jennifer and Gayle - were trained, she says, in running a household. ‘By the age of six, I could clean the kitchen, wash the clothes, vacuum and change my baby sister’s diapers.’ They adored their father, Jim. Their mother, Kathleen, was a nightmare.

One day their mother shut all four of them – aged between one and eight – in the garage for several hours. It was freezing cold and they had no coats, hats, gloves or shoes on, until their father came home and rescued them. Another time, she beat the sisters with a belt until their flesh was flayed as a punishment for Harding drinking some of her Coke.

Kathleen was a sociopath and a narcissist. Later, the girls struggled to understand why their father had not left her.

‘He felt he had ruined her early life,’ Harding explains. ‘She had four children by the age of 25, when she was clearly not fit, because of her nervous state, to be able to take on that kind of stress. I think he felt that it broke her, and that he had a responsibility, not to abandon her, but to see that she was properly medicated so she wasn’t hurting people. But what he didn’t see was that she was also cruel and duplicitous – she was a different person when he wasn’t around.’

But after the garage incident, he got professional help for her. ‘And it was shortly after that she found Jesus Christ and we had a couple of years that were very different,’ says Harding. But then she started drinking.

In the days that followed the kidnap, Harding didn’t really discuss what happened with her father. It was his way of protecting her. She went back to school the following Monday and school became her respite. She was helped by her favourite teacher, Kent Friesen, who gave her ‘the championship coaching speech of my life’. Shortly after the kidnap, her father moved the family to the neighbouring state of Iowa.

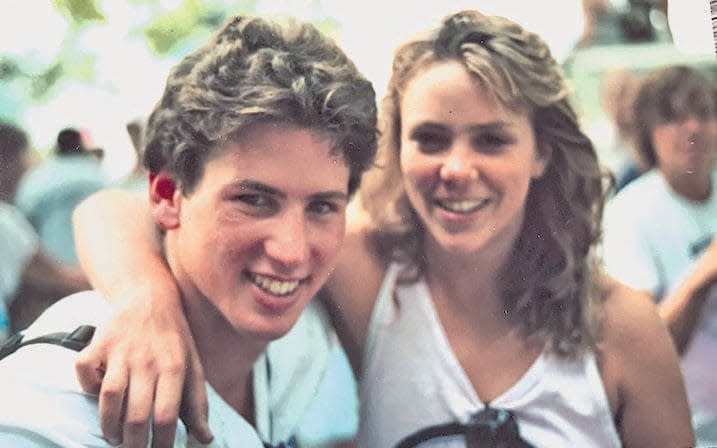

When she was 18 her mother kicked her out of the home and she moved to Washington, DC, where she did a degree in politics at George Washington University, while working for US Senator Gary Hart’s campaign. She was 23 when she encountered her first bout of depression, which she tackled by embarking on a cross-country biking expedition to raise money for charity. On the trip she met Thomas Harding, a British student on a gap year. She moved to England in 1992 and they were married 10 years later.

At 28, Debora started to experience psychosomatic fits and episodes of sudden paralysis. Then anxiety took hold – but still she didn’t associate it with her trauma. She was happy and had met a man she loved. In 2001, they moved to West Virginia. Thomas was writing a book and they were home-educating their children, Kadian and Sam. It was here that her anxiety became acute, taking the form of a fear she might harm her children, and she saw a psychiatrist. When she told him about her mother’s treatment of her, and being kidnapped at 14, he was awed by her resilience and suggested that the reason she had survived the kidnapping was because of the skills she had learned coping with her mother.

Harding was further unnerved by a series of coordinated sniper attacks in the Washington, DC area, in which 10 people were killed. This again triggered her PTSD and a specific fear of Charles Goodwin – that he might come after her – returned. Her husband suggested it could be helpful to find out where Goodwin was and what had happened to him. With help from the FBI, they tracked him down. He was back in prison but coming up for parole in six months’ time. Harding obtained the police reports and court testimonies, and Goodwin started to become a human being, rather than a faceless monster, in her mind.

Before he kidnapped Harding, he had been arrested for carjacking and, having spent six months in Douglas County Jail, where he was beaten up and had his jaw broken, he was sentenced to five further months in a young offenders’ institute. Released in November 1978, Goodwin went to the courthouse with a gun, intending to kill the judge, but bumped into him in an elevator, and when the judge was friendly and solicitous, he lost his nerve.

Then he came up with the kidnap idea.

Harding tells some of Goodwin’s story in the book, reconstructed from police reports and interviews: how he was bussed to Norris Junior High (bussing was a system aimed at desegregation whereby black pupils were bussed across town to white schools); how he’d never known about racism until he was attacked at school and in jail.

‘There’s a hell of a lot of personal anger at the state,’ says Harding. ‘He felt like he was an innocent kid who had been thrown into an adult holding tank at the age of 14, where he was assaulted. Omaha was one of the last places in America to be desegregated and bussing was an exciting thing to be part of because you felt like you were actually doing something. But we didn’t quite understand what racism was at that age – none of us did. He was in his neighbourhood, I was in mine, and we weren’t really aware that there was a big difference between black and white because we were in our own little universes.

‘But then as teenagers you’re suddenly thrown into this social experiment and he went to white school and was a constant victim of racist attacks, and the teachers weren’t taught the skills to manage things.’

The references to racism about two thirds of the way through the book are the first indication that Goodwin is black. Harding made the decision not to point that out at the beginning after careful consideration. ‘The racist trope of the black man raping the white girl is grossly still alive,’ she wrote in an email to me. ‘We live in a racist society that is not colour-blind, and I did not feel it right to deny him the oppression that shaped his external world. But I do feel that to suggest the kind of devastating pain that Goodwin inflicted is the fault of society, is to err grossly in a different direction.’

While researching what had happened to Goodwin, Harding came across the idea of restorative justice: a practice that facilitates dialogue between victims and offenders. There are many reasons for doing it – if the victim has questions, or is seeking some sort of reconciliation, or wants the perpetrator to be made aware of the consequences of their crime. Harding contacted the Nebraska Department of Correctional Services and, via a mediator, Goodwin agreed to the victim offender dialogue – he had a parole hearing coming up after all (‘I don’t think he was doing it for personal growth reasons,’ she comments wryly). She was warned about the pitfalls of such an idea – including the possibility of re-traumatisation or the fantasy that there might be some kind of happy ending.

‘After all these years, I just wanted to rid my brain of the image of that ski mask and to see the human with the eyes,’ she writes in the book. ‘I wanted to establish that the person who attacked me was not an evil monster lodged permanently at the back of my head like that blade he had pressed into my skull. I wanted to dispel the ghost of him in the same way Dad had taught me when he offered me a nickel to look under the bed all those years ago in Maine when I was frightened of monsters hiding there.’

She also wanted to know if she had been specifically targeted. Her questions were relayed via a mediator; Harding did not speak to Goodwin directly and his answers were emailed to her. He admitted to everything – it was exactly as she remembered it. He said that after the assault she ‘had gone so limp he thought she had died’.

After reading the email, her fear and rage ebbed away and she was somehow grateful that he had verified her own memory of the attack. It was followed by a cassette of the interview in the post which she and her husband listened to; they were surprised by how soft-spoken Goodwin was. Harding wanted to see what he looked like, so she requested a filmed interview. Goodwin refused. And she caught him out in a lie – he lied about a letter he had written her from jail, after he had obtained her address by subterfuge. Harding became angry, and decided to testify at his parole hearing. ‘I thought, I’ve got a duty of care to let the parole board know who they’re releasing,’ she says. ‘And so I went back to testify.’

So in September 2003, Harding found herself in the cafeteria of the correctional facility in Lincoln, Nebraska, which served as a holding space for inmates before they went into their parole hearing. She had just wanted to see what Goodwin looked like, but she knew immediately which one he was and, without planning it, heart thudding, she went up and introduced herself.

Goodwin stood and shook her hand. She talked to him for about 20 minutes – about his plans for the future, about work, about the family and friends who might look out for him on his release. And she told him the devastating effect the attack had had on her life. And she wished him good luck.

‘How did you feel after that?’ I ask her. ‘I felt high as a kite,’ she says. ‘I’d walked up to my worst fear in life.’ What surprised her, she says, was ‘his likeability. It was a bit unnerving. He didn’t miss a beat. He’s a charming psychopath – he certainly wasn’t scared of me approaching. And you so want to root for these guys. You so want them to be able to change.’ He answered all her questions and apologised to her. He promised to ‘honour her’ by not committing acts of violence again.

By the time she met him, Goodwin had spent a quarter of a century in Nebraska state prisons. Three years after their meeting, he was arrested in Omaha and sentenced to seven years in prison and four years of supervised release for conspiracy to commit extortion.

It took a very long time for Harding to even contemplate writing this book. She had wanted to write ever since discovering Henry Miller in her early 20s. She knew she had a story to tell, and had interest from agents and publishers, but kept getting distracted by events in her life.

But then something happened that derailed everything. Her 14-year-old son, Kadian, was killed in an accident. He had just picked his bike up from the repair shop and had been cycling with his father, cousin and friends, when his brakes failed as he went downhill at speed, into the path of a van. He was killed instantly.

This was eight years ago, but Kadian is still everywhere in their lives. A huge photo of him dominates their kitchen; his father wrote an amazing memoir called Kadian Journal. A mannequin covered in hundreds of buttons sits in the hall – his mother made this after he died, it was her meditative way of building a second skin. July 25th was the eighth anniversary of his death, and the family have just returned from an annual camp-out that they hold in Kadian's honour, with up to 30 or 40 of their friends and relations.

‘Tell me about Kadian,’ I say. And her face lights up. ‘He was my first child. I’ll never forget the moment I laid eyes on him. My world was 100 per cent OK – there was nothing, nothing I couldn’t fight, and everything that came before it was immaterial. Our personalities just aligned, and we were always on the same page. That total love bubble – for 14 years. My daughter is amazing as well.

‘It’s absurd,’ she goes on. ‘I just got shocked out of being shocked any more, which is why later I was able to write the book in the disassociated manner that I did. One of the things that makes me sick is – he was 14. I know how much life I’ve had since I was 14. He loved life, he loved people, he was so sharp and tuned in and creative and he would have been a magnificent adult. But it’s not helpful to try and imagine a future he didn’t have, because he had a perfect 14 years, and that’s a blessing – and he died a painless death.’

On the way back from the pub, we walk past Bedales school, which is where Kadian and Sam were educated. It’s a school with glorious grounds and lovely buildings dedicated to arty pursuits, and Harding cannot speak highly enough of its head, who orchestrated a memorial tribute at the school for Kadian, a few months after he died: eight set pieces highlighting all the things Kadian had loved. ‘We wanted people to walk away with a sense of Kadian.’

It was a lifeline for Harding. At that point, she says, ‘We were out of our minds.’

Like many other bereaved parents, she and Thomas will never get over their loss but they have learned to accommodate grief. It took several years for her to be able to pick up a book or write anything. ‘My brain, my emotional compass – none of it worked the way it once did. I literally had to learn how to put sentences together again.’ But when she found herself able to read books again, it was the essays of the 16th-century philosopher Michel de Montaigne, who was himself grieving over losing people close to him, that inspired her to write the book.

‘Life would be tragic if it weren’t funny’ is a quote from Stephen Hawking on the frontispiece. And Harding’s book is funny, in a deadpan, oddball way. Each short chapter has a heading, like a little series of essays – ‘In which I learn of the existence of ghosts’, ‘In which Charles graduates to being a violent criminal’ – which makes some of the difficult material somehow easier to digest. The detail of her childhood is extraordinary and builds up a vivid picture of her wayward family, particularly of her father and what she calls his ‘creative genius for comedy’. (The octopus from the title comes from an imaginary octopus that he pretended they had picked up in Florida, and which lived on the roof of their car and had to be rehoused in a pond.)

‘I wouldn’t have survived my son’s death if I hadn’t gone on that journey [confronting Goodwin] and come out of it the other side feeling as though I have the power, which I have at the end of the book,’ she says. ‘I also have a civic responsibility to talk about violence and its long-term effects, which is something we don’t do enough for victims. If you’re a survivor and you’re a high-achieving professional – but then sometimes you find yourself staring at the walls, or hallucinating, or not being able to function. But I took care of it. That’s not to say I don’t have a lot of heavy lifting to do when it comes to self-management – working out and sleeping well, all the things you do to look after your mental health – I’m pretty razor-sharp on that, but I’ve never had those other issues again.’

In 2007, Harding’s beloved father killed himself. He was 67, and in perfect health, but had been suffering from depression. The last contact Harding had with her mother was when she asked her for some of her father’s ashes. Her mother refused. ‘I didn’t think she could actually hurt me any more,’ says Harding. ‘But when my son died I thought, I hope she can put a card in the mail, or make some kind of acknowledgement of the loss – and there was nothing.’

Her mother now lives alone in Arizona. Harding is close to her sisters, except for her older sister Genie, who removed herself from the family orbit early on. There is no conventionally happy ending to this story. But there is an unconventional one. Goodwin was not a reformed character, and along the way Harding lost her father and her son. But her book is a beautiful and exacting monument to resilience and recovery, and a memorable tribute to her father; and the power she drew from writing it is immeasurable. She looked under the bed and she survived to tell the tale.

Dancing with the Octopus: The Telling of a True Crime by Debora Harding is published on 27 August (Profile Books, £16.99)