Justice tied together with clotheslines

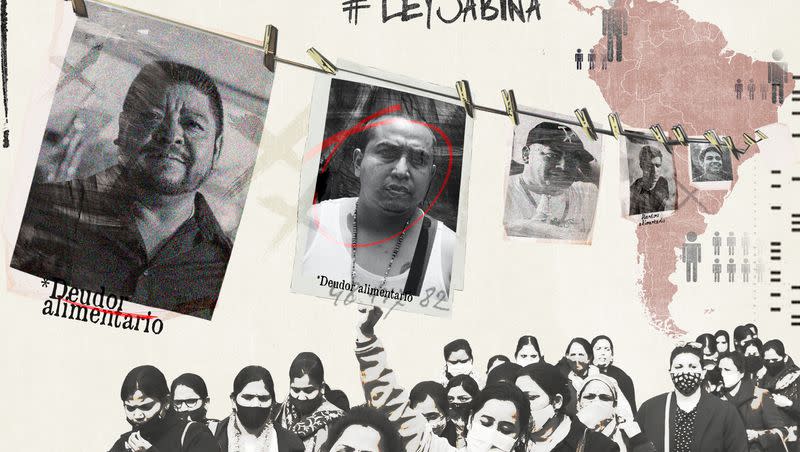

In July 2021, more than 300 women and their children gathered under clotheslines strung across Oaxaca’s Santo Domingo Square, the threads weighed down with photographs of wanted men, plastered with accusations: “DEUDOR DE PENSIóN ALIMENTICIA” (child support debtor). Some women penned their children’s father’s full name, job title and the amount of pesos they’d left outstanding.

Each poster represented a story of paternal absence enabled by a culture with few avenues to offer reprimand, a fact that fueled Diana Luz Vázquez to organize the “Debtors Clothesline” protest in the first place. “If justice doesn’t reach them, let shame do it,” says Luz Vázquez, who is herself a daughter and granddaughter of child support debtors. “Our grandmothers and mothers say ‘leave it to God’ or ‘leave it to karma’ and never take action. They don’t want to provoke scandal. But many moms have now realized that this is not normal and this is not OK.”

In Mexico, about 67 percent of single-mother households don’t receive child support. Even though the right to receive these payments is protected by federal law, the power to determine what’s owed and enforce those transactions falls on the nation’s court system. Discretion belongs to judges, unlike countries with government bodies solely dedicated to child support oversight like the United States’ Office of Child Support Enforcement. The backlog of cases and high costs of legal fees mean court proceedings often take too long and grow too expensive for many single-parent households to pursue. Debtors can regularly evade child support payments without consequence, which further enables a culture of shame, cyclical poverty and strict gender roles.

Related

“There’s a real issue with men not recognizing their paternity. … And of course, there’s no economic commitment,” says Monse Torres, a single mother of two from Zacatecas, Mexico, who now volunteers for Frente Nacional de Mujeres Contra Deudores Alimentarios, an organization focused on uniting women against child support debtors. She says her son’s father does not recognize his 18-year-old child and has not paid his child support for 15 years. That lack of parental and financial involvement can cause children to perform poorly in school, suffer behavioral problems and hurt their self-esteem. “When I was a child, I always wondered why my father wasn’t with me,” says Torres’ son, Emilio. “Besides the money, what’s important is that a father shows love and willingness to meet their kids, to be with them, to support them and love them in other ways.”

What are ‘Debtors Clothesline’ protests?

The “Debtors Clothesline” protests and the larger movement they represent use these deep-set cultural norms in Mexico to create change. In 2021, a federal bill titled “Ley Sabina” (Sabina’s Law) was introduced to the Mexican Senate. It included a directive for Mexico to create its first national registry of child support debtors — to function as a transparency tool women could reference before starting families with men who have a proven record of disappearance, as well as streamline the government’s ability to identify debtors and enforce harsher consequences. The first protest in Oaxaca was meant as a last-ditch effort to bring attention to that bill. It went viral. The movement has since spread to each of Mexico’s 31 states, the capital city and throughout Latin America. It has outed high-profile athletes, musicians and politicians as child support evaders. It placed a massive spotlight on the issue, and unprecedented pressure on the Mexican government to exact accountability.

In March, the Mexican government approved the creation of the national registry proposed in “Ley Sabina.” The registry is updated monthly and makes debtors’ identities public. Judges review the cases of the parents listed in the database to determine whether they ought to be barred from obtaining driver’s licenses and passports, as well as from running for public office or judicial positions at both the local and federal level.

Re-creations of the Oaxaca protest still echo across Latin America. A similar string of fliers and demands appeared in Paraguay’s capital this May; printed faces lined the exterior of Argentina’s Supreme Court in June. In Mexico, mothers like Luz Vázquez and Torres continue to push for more changes. Their proposals include laws to forbid debtors from receiving custody of their children, and for the government to impose credit score repercussions and deny consular IDs as further incentives to honor payments. Luz Vázquez is convinced it will take all the moral and financial encouragement possible to correct a culture of fatherlessness that spans generations. But she’s equally convinced that correction is more possible now than ever before.

“Besides the money, what’s important is that a father shows love and willingness to meet their kids, to be with them, to support them and love them in other ways.”

Monse Torres works overtime as an accountant assistant in Zacatecas, located in central Mexico. She can’t take family vacations or request any time off in order to care for her four-year-old daughter and 18-year-old son. “When a mother is alone,” she says, “the culture around her says to her, ‘You can do it alone. You must be strong, you don’t need to ask for help.’” In the state where she lives, about 20 percent of residents experience moderate poverty and women make up only 39 percent of the workforce. The realities of parenthood are shaped by community and geography. In a patriarchal culture like Mexico’s, gender roles play a substantial role in what it means to be a mother or father.

Only about half of single mothers in Mexico are employed and make up to 20 percent less than their male counterparts. Single mothers who are informally employed — as domestic workers, for example — can’t access social security or health benefits. Yet when mothers speak out against the economic and cultural forces that bind them, they’re characterized as “scorned women,” demanding and difficult. Meanwhile, the men are yoked with the role of “provider.” A study of single fathers from Mexico City in 2010 published in the Autonomous University of the State of Mexico’s quarterly academic journal, Papeles de Población, found that fatherhood is culturally defined as an obligation of men to fund a home. If a father is unable to afford child support, that can label him as a failure.

Luz Vázquez, who functions as the spokesperson of the international “Debtors Clothesline” movement, has faced her own critics. In February 2022, she received harsh scrutiny after she got into a minor car crash while intoxicated with her daughter in the passenger seat. Neither mother nor daughter was injured, but a video posted online made her a target for accusations of hypocrisy. The assumption was: How could she speak out against irresponsible fathers after this? How could anything she advocates for be trusted? She says her mistake is wrongly used as a way to discredit the movement, and that she still receives hateful comments across social media.

These societal expectations can mean men and women are expected to act as caricatures of the masculine and feminine. Since women are idealized as caring, subservient and self-denying homemakers, they are also typified as the parent responsible for raising their children, while fatherhood is seen as a largely transactional and voluntary relationship. “Mexico has a very patriarchal culture, and that culture is the education that men get from their homes,” Emilio says. “These ideas are that the man has more privilege than the woman, that men are never responsible for when a man gets a woman pregnant. It is seen in Mexico as something funny, something to laugh at … and the woman is always the one who’s degraded.”

‘Other kinds of legal guardrails’

Civil codes from the 19th century established a man as a father only through marriage or if he chose to formally recognize his child either with public displays or financial support. Nara Milanich, a professor of Latin American history at Columbia University’s Barnard College, dissected this notion in her 2017 academic paper for the World Policy Institute, “Daddy Issues: Responsible Paternity as Public Policy in Latin America.”

“The protests seem to me part of a long history of contestation over the role of fathers and the responsibilities of fathers to children in Latin American societies,” Milanich says. “The large majority of children are born outside of formalized unions. Marriage is not a normative practice (in Latin America). But what that means, perhaps, is that we need other kinds of legal guardrails or assurances to ensure that whether or not parents are formally married, fathers still have responsibilities to their children.”

“I f justice doesn’t reach them, let shame do it.”

Children haven’t always been a priority of the Mexican government. The General Law for the Protection of Children and Adolescents, Mexico’s legal framework for addressing social issues involving minors, is less than a decade old. It only passed in December 2014 as a result of international treaty requirements. The law created the nation’s first federal agency to oversee policies that involve children’s and family rights. Prior to its passing, a jumble of government bodies with a lack of structure caused child protection issues to go underreported and overlooked. This extended to issues involving child support, which, while legally required in Mexico, went frequently unenforced for generations.

But the creation of the national registry for child support debtors now means the government’s enforcement of these laws is more visible than ever. The database is publicly accessible and updated by a federal agency every month. A single parent who is owed child support payments can report the debtor to have them put into the system. The debtor will then have to provide the courts proof of payments to have their name removed. This gives single parents who don’t have the financial means to afford legal representation a chance to prove their case in court. For those who owe payments and possess the means to afford them, penalties like revoked travel documents and even difficulty acquiring real estate offer solutions. Rather than jail time, which is the traditional penalty in Mexico, financial repercussions motivate debtors to pay in a way that benefits the children who are owed support. Incarceration costs everyone through taxpayer dollars and prevents the debtor from being able to pay what they owe, but these new sanctions minimize harm by costing only the debtor. “What we really want is for mothers not to end up paying for the process of getting justice,” Luz Vázquez says.

Children living in poverty

Of the more than 37 million children in Mexico, UNICEF estimates that more than half live in poverty. That rate has steadily climbed over the last few years with an uptick in shuttered businesses and layoffs prompted by the Covid pandemic, a reality that’s hit working-class families the hardest. As poverty has worsened, so too have nutrition and school attendance among children. Though the burden of poverty on children isn’t unique to Mexico, it’s more relevant here than most anywhere else, as more single-mother households exist in Latin America than any other region in the world.

An academic study published this year by Rutgers University assistant professor Laura Cuesta in the Journal of International and Comparative Social Policy found the poverty rate for single-mother families is substantially higher than both two-parent families and single-father families in 36 of 37 surveyed nations because of factors like gender pay gaps and diminished social standing. Less than half of these households in Colombia, the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, Panama and Paraguay receive any child support.

Yet families have taken action into their own hands to change what’s possible for the next generation. “A positive outcome of the life I have lived is that I want to be present,” Emilio says. “I want to be the opposite of what my father was.” He’s accompanied his mother to the “Debtors Clothesline” protests for nearly three years. “He’s very passionate about the movement because he doesn’t want other children to go through what he has been through,” Torres says. “I owe some justice to Emilio. The tiny piece of the world that I’m leaving, … I want it to be a better place for when they’re older.”

This international movement simply started with a day of posters dangling from clothespins in Oaxaca two years ago. Today, Luz Vázquez is seeing it make real changes. As of last year, Sabina’s father began paying child support. “He said that had he known it’d come to this,” she says, “he’d have given me the money already.”

This story appears in the December issue of Deseret Magazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.