The Journalist and the Pharma Bro

Almost every weekday for six years, Christie Smythe took the F train from Park Slope downtown to her desk at Brooklyn’s federal court, in a pressroom hidden on the far side of a snack bar. Smythe, who covered white-collar crime for Bloomberg News, wore mostly black and gray, and usually skipped makeup. She and her husband, who worked in finance, spent their free time cooking, walking Smythe’s rescue dog, and going on literary pub crawls. “We had the perfect little Brooklyn life,” Smythe says.

Then she chucked it all.

Over the course of nine months, beginning in July 2018, Smythe quit her job, moved out of the apartment, and divorced her husband. What could cause the sensible Smythe to turn her life upside down? She fell in love with a defendant whose case she covered. In fact, she broke the news of his arrest. It was a scoop that ignited the internet, because her love interest, now life partner, is not just any defendant, but Martin Shkreli, the so-called “Pharma Bro” and online provocateur, who increased the price of a lifesaving drug by 5,000 percent overnight and made headlines for buying a one-off Wu-Tang Clan album for a reported $2 million. Shkreli, who was convicted of fraud in 2017, is now serving seven years in prison.

“I fell down the rabbit hole,” Smythe tells me, sitting in her bright basement apartment in Harlem, speaking publicly about her romance with Shkreli for the first time. The relationship has made her completely rethink her earlier work covering the courts, and as she looks back on all of the little decisions she made that caused this giant break in her life, she says she has no regrets: “I’m happy here. I feel like I have purpose.”

More than four years earlier, in January 2016, Smythe stood outside the Bryant Park skyscraper where Martin Shkreli’s company Turing Pharmaceuticals had its offices, clutching a camera, about to meet the man himself for the first time. She was so anxious that she hadn’t eaten all morning. One month prior, Shkreli had been charged with defrauding investors at hedge funds he’d run earlier in his career, and he made a habit of regularly taunting journalists like her. How do I manage the situation? she remembers wondering.

Growing up outside Kansas City, Missouri, Smythe “was terrified of the sound of my voice,” she says. In high school, however, her passion for reporting helped her finally overcome her shyness. Smythe had a stubborn streak, railing in her Catholic-girls’-school newspaper about fines for wearing uniforms improperly. When her parents asked her to take her brothers to church, “she would defiantly take us to McDonald’s" instead, her brother Michael Smythe says.

Smythe attended the journalism school at the University of Missouri and worked for two small newspapers before moving to New York in 2008. After working for a legal news company, she started covering Brooklyn federal court for Bloomberg News in 2012. It was a high-pressure job—Bloomberg tracked how many seconds its reporters filed stories ahead of their competitors—but she was well regarded at the company and churned out reliable stories over the years. Her personal life was going well, too; in 2014, she married her boyfriend of five years, who worked in investment management.

By early 2015, Smythe learned from a source that Shkreli was under federal investigation for securities law violations. At that point, Smythe had no idea who he was—few people did—but she did some research and learned he was a brash, self-taught young executive who’d started hedge funds in his twenties, then moved on to found pharmaceutical companies Retrophin and Turing. When Smythe phoned Shkreli, she was expecting a standard “No comment.” Instead, he argued she “had no idea what I was talking about.” Confident in her sourcing, she published the story anyway, breaking the news of the investigation. But because Shkreli wasn’t well known yet, it didn’t make much of a ripple.

That fall, though, Shkreli turned himself into a self-styled villain overnight when he raised the price of a drug called Daraprim, which is used to treat a type of parasitic infection that can be life-threatening, by 5,000 percent. Outrage followed, with headlines like “Martin Shkreli: A New Icon of Modern Greed,” and “Martin Shkreli Is Big Pharma’s Biggest A**hole.” Then–presidential candidate Hillary Clinton said the “price gouging” was “outrageous.” Her opponent Donald Trump said Shkreli looked like a “spoiled brat.” Shkreli responded with livestreams and Twitter fights: “In DC. If any politicians want to start, come at me,” he tweeted.

So when Smythe learned the federal investigation of Shkreli had moved forward and he was about to be arrested, “I had the sense that there would be massive schadenfreude,” she says. The charges alleged that Shkreli had made bad bets in his hedge funds and tried to cover up the losses by lying to investors about how the funds (and investors' money) were performing. He was also accused of plundering his pharmaceutical firm Retrophin to pay back the hedge-fund investors. In December 2015, Smythe broke the story of Shkreli’s arrest, and “the internet lit up,” she says.

In a packed courtroom for Shkreli’s arraignment, Smythe watched as Shkreli, dressed in a gray hoodie, pleaded not guilty. He was allowed to go home and continue working at Turing after posting a $5 million bond. The next month, Shkreli called Smythe. I was sitting next to her in the Brooklyn pressroom, where I covered courts and the Shkreli case for the New York Times, when she took the call. I overheard her startled conversation with him, in which he told her, “I should’ve listened to you,” referring to the first time they spoke about the investigation, back when he said she didn’t know what she was talking about. During the call, she managed to wrangle an in-person meeting with Shkreli four days later. She was hoping to profile him and brought along her camera, just in case.

When Shkreli walked in for the one o’clock meeting, this time wearing a black hoodie, his hair greasy, he immediately “started giving me a spiel,” she says. He wanted the talk off the record, and proceeded to show Smythe spreadsheet after spreadsheet with investors’ holdings in his funds. He argued that they were all ultimately paid back. “You could see his earnestness,” Smythe says. “It just didn’t match this idea of a fraudster.”

After that, “he kept toying with me for a while,” Smythe says. He would dangle an on-the-record interview and then grant one to one of her competitors. Smythe had to remain cordial; Shkreli kept making news—he bought the Wu-Tang album, he smirked when testifying before Congress about drug pricing—and coverage of him at Bloomberg fell to her. One evening when Smythe called him for comment, a tiny shift occurred. Shkreli was looking for a new lawyer and asked her for advice. She felt flattered, she says, and offered her opinion. “It really felt like he didn’t have anybody to talk to that he could bounce ideas off of,” Smythe says. “I was like, ‘All right. I guess I can do that.’ ” He sounded “ragged and fragile, and I got concerned he would commit suicide because all this stuff was all happening at once.” Still, her job came first: She pre-wrote an obituary for Shkreli in case he did, in fact, kill himself.

She continued to angle for a profile, asking Shkreli to meet her in person again in the spring. He chose a wine bar near his Murray Hill apartment. When they arrived, he greeted the waiter in Albanian—his parents are Albanian—and ordered a Cabernet; she, unable to focus on the menu, did the same. After he said he’d consider letting her write a feature, they started talking about his childhood. The Brooklyn-born son of immigrants who worked as janitors, he’d skipped grades and dealt with serious anxiety as a child. Smythe had anxiety, too, and they connected over how they’d both succeeded in competitive New York fields as outsiders without Ivy League educations. When he said he could probably get the wine for free, given his Albanian connection, she, conscious that journalists shouldn’t take freebies, declined.

Through the summer, Shkreli kept up his game of cat and mouse, offering Smythe tantalizing hints about evidence, then ghosting her for weeks over some perceived offense. In fall 2016, Smythe started the prestigious Knight-Bagehot Journalism Fellowship at Columbia University. That spring, she wrote about Shkreli for a class, “describing how manipulative he was to reporters,” says her professor, Michael Shapiro. She wrote “quite candidly about how he had so successfully drawn her in.” Shapiro worried that Shkreli was stringing Smythe along in order to make “her evermore grateful for access.” And “once that happens, you’re at a profound disadvantage as a reporter,” Shapiro says. She showed the essay to Shkreli, and after he read it, he told her, “You should write the book”—as in, a biography and memoir of Shkreli. Shapiro felt that the journalist/source relationship was already muddy, and cautioned Smythe against writing a book on someone “so manipulative.” Smythe remembers Shapiro telling her, “You’re going to ruin your life.”

“Maybe I was being charmed by a master manipulator,” Smythe tells me. But she felt she could maintain control. She had wanted to write a book since she was a kid and decided to do it, so she found an agent and started drafting a proposal. In April 2017, Shkreli invited Smythe to a talk he was giving to a Princeton University student corporate finance club as fodder for the book. The club sent an SUV to pick them up; a dean shook their hands. Smythe felt a stir when Shkreli mentioned her: “Even if you find an honest reporter—I made friends with one, she’s here right now,” he told the audience. Afterward, Shkreli met with students at a brewpub. “Martin’s mobbed with kids, people talking to him, and he’s really animated and excited,” she remembers. When Shkreli went to the bathroom, Smythe stepped in to entertain the students. “It almost felt like I was a political wife,” she says.

A line snaked outside a sixth-floor courtroom in Brooklyn’s federal district court on the first day of Martin Shkreli’s trial in June 2017. Inside, spectators wedged onto hard benches, supporters of Shkreli to the left, journalists to the right. Even jury selection had been eventful, with potential jurors dismissed for saying Shkreli was “the face of corporate greed” and that “he disrespected the Wu-Tang Clan.” A prosecutor accused Shkreli of “telling lies on top of lies on top of lies” to investors, as Shkreli made faces and took copious notes. After his defense lawyer argued he had good intentions and had ensured investors ultimately made their money back, Shkreli stood and patted him on the shoulder.

Smythe wasn’t covering the trial for Bloomberg (she was on book leave), but she was there in the courtroom every day, sometimes sitting with Shkreli’s supporters—friends from the internet who’d rarely interacted with him in person until then. Once they all ate lunch with Shkreli in the court cafeteria, and they also went out for drinks a couple of times after the proceedings adjourned. Smythe went to court to find out "who are his core people, who should my sources be,” and hear “backstory” from Shkreli on each day’s testimony.

Shkreli’s antics didn’t stop during the trial. He rolled his eyes at testimony. He told a roomful of reporters that the prosecutors were “junior varsity,” causing the judge to bar him from talking publicly in or around the courthouse. He livestreamed at home after court, meowing at his cat and playing online chess. When Emily Saul, then a New York Post court reporter, was covering the trial, Shkreli or one of his fans created a fake Facebook page for her and boasted that he and Saul were in a relationship, Saul tells me. He also bought emilysaul.com for less than $12 and offered to sell it for thousands.

Smythe’s take on this is, “He trolls because he’s anxious,” she tells me, and “he really, really wants to be somebody.” She began defending him publicly as she emphasized her access to him to publishers in an attempt to sell her book. During the trial, she visited his apartment and listened to the Wu-Tang album—“for research,” she says. Afterward, Smythe tweeted a photo of her holding the album, tagging a female journalist whom Shkreli had harassed online and writing: “I don’t think he would hurt a woman, even a journalist. Behold: me and the #wutang album.” Of her increasing involvement with Shkreli, she tells me now, “These are incremental decisions, where you’re, like, slowly boiling yourself to death in the bathtub.”

In August 2017, Shkreli was convicted of three of eight counts; his sentencing hearing was scheduled for January. Shkreli bragged he’d do minimal, if any, prison time.

"He's just using you," Smythe’s husband had told her early on, after she had just gotten off late-night call with Shkreli. “For what?” she had replied. The argument escalated. Her husband felt she was risking her journalistic reputation by “getting too sucked into this bad person,” Smythe says. She felt he was trying to micromanage her career. They scheduled a couples counseling session.

In September 2017, Smythe went to see a high school friend named Meredith Hartley on the West Coast, where she also conducted some book research. Hartley says Smythe talked about Shkreli the whole weekend. “I asked if Martin had ever made a move on her, and she said no, he’d always been very professional with her,” says Hartley, who was a bridesmaid at Smythe’s wedding. Hartley figured Smythe just had a little crush.

Later that month, Shkreli offered his online followers $5,000 for a strand of hair from Hillary Clinton, who’d criticized his drug pricing. His lawyer said it was his usual online “immaturity, satire,” but prosecutors filed a motion asking that he be jailed until sentencing in response. By then, Smythe’s book leave was over and she was back covering Shkreli for Bloomberg. She called him when she heard about the Hillary hair incident, and “he just railed at me about freedom of speech,” Smythe says. But the judge jailed Shkreli; he walked into court with his lawyers and, after, was placed in a holding cell by U.S. marshals. The minute she left the courtroom, Smythe texted and emailed Shkreli’s friends, asking if he had his medications and arranging for someone to retrieve his cat. Then she filed a story from the pressroom. "Ms. Smythe’s editors did not know about these actions,” a Bloomberg News spokesperson told me. “Had they been aware of them at the time, at a minimum, she would have been immediately taken off the beat.”

At home later that night, she couldn’t sleep; her Fitbit measured her resting heart rate at 10 beats higher for a week afterward. “I was still in denial about it, but this really hit me hard,” she says of Shkreli’s sudden jailing. Her physical reaction made it harder for her to ignore that something more than a journalist-source relationship might be developing.

Smythe pressed Shkreli to let her visit him in jail, and he agreed to a November date. In the visitors’ room, unsure of what Shkreli liked, Smythe spent $30 on vending-machine snacks. When he was brought in, she hugged him, and they sat down to talk, struggling to hear each other over the other visitors. She microwaved a hamburger for him, and they talked about jail. When the hour-long visit ended, she hightailed it to the first counseling session with her husband. He had refused to move the appointment, and she wouldn’t reschedule with Shkreli. She arrived at the hour-long session 52 minutes late.

Who was “Individual-1”? That was the question reporters asked as they read prosecutors’ sentencing submission. Asking the judge to give Shkreli a lengthy 15-year sentence, prosecutors cited emails between a person known as “Individual-1” and Shkreli, sent through the jail email system, where all messages are monitored. Prosecutors excerpted the emails to argue that Shkreli was faking remorse, telling Individual-1 that he would do “everything and anything to get the lowest sentence possible.”

Seeing her conversation with Shkreli, knowing full well she was Individual-1, was the moment Smythe realized she could no longer cover Shkreli for Bloomberg. “I knew I was a part of the story at that point,” she says. She alerted her editors and switched to covering different cases. By then, book publishers had passed on her proposal; they wanted a caustic take on Shkreli, which she refused to write. So she focused instead on selling movie rights to the book proposal, attending Shkreli’s March 2018 sentencing for research. Zipping between supporters, journalists, and lawyers in the courtroom, Smythe says, “it almost felt like I was giving a dinner party.” Reading Shkreli’s unremorseful correspondence with Smythe aloud, the judge sentenced him to seven years. Smythe remembers Shkreli telling her that his lawyer opined that the emails had added two years to his sentence, which Smythe says she feels sick about to this day.

With Shkreli in prison, Smythe “definitely felt like an advocate for him,” she says. He sent her letters from other journalists he’d received, and she tweeted photos of them with derisive comments on the reporters’ approaches. She challenged tweets disdainful of Shkreli, and told supporters how to contact him. She says she did this partly to correct false information—he didn’t increase the price on the EpiPen, for instance, and he is 5'10", not 5'7"—and partly out of “professional jealousy.” Says Smythe, “Lots of reporters were tweeting or writing stories about interactions with Martin, and I had a rich store of knowledge I hadn’t been able to use in my book or an article.” Smythe wanted to tell a different narrative of Shkreli: that he’d built his companies from scratch, that he could summon data with a near-photographic memory, that his villainous public persona was a mask. “I wanted to get the rest of the story out there,” Smythe says. “And I couldn’t.”

In summer 2018, her editor summoned her to a conference room at Bloomberg headquarters. When she arrived, her editor and an HR rep sat waiting. They’d already warned her about her tweets regarding Shkreli, which she believed she'd complied with, though she continued tweeting about him some. Now her superiors told her that behavior was biased and unprofessional. Smythe understood their concern and quit on the spot, hugging her editor on her way out of the building. "Ms. Smythe’s conduct with regard to Mr. Shkreli was not consistent with expectations for a Bloomberg journalist,” the Bloomberg spokesperson says. “It became apparent that it would be best to part ways. Ms. Smythe tendered her resignation, and we accepted it."

At home, Smythe’s stress over Shkreli and her now-uncertain work future compounded her problems with her husband. “I’m not going to say it was wrong for him to be concerned,” she says, but the fights got too sharp and too frequent. They’d been considering divorcing since the start of the year, and decided to move ahead.

At the time of their separation, Smythe had been visiting Shkreli for months. She took a 6 a.m. prison van from Manhattan to see him when he moved to a New Jersey prison. When he was transferred to a prison in Pennsylvania, Smythe, who used to get panic attacks when driving, got a license so she could still see him. They talked about Picasso, about philosophy, about her dog and his cat, their conversation flowing “like water.” He told her she was one of the only people allowed to visit him, and mused about running for office or starting a podcast when he got out. “That belief in himself, although it may seem delusional at times, it draws you in,” she says. “I don’t know if everything he was saying was true, but maybe like 1 percent is, and that’s awesome on its own.”

Soon after quitting Bloomberg, Smythe visited Shkreli again, fuming about the book industry’s rejection of him—and her. “I was so angry at the establishment, and people who wouldn’t let me tell my story in the book: publishers, Bloomberg, everybody,” she says. Without her job or her marriage “that totally eroded any defenses I had left.” Before, she had tamped down the sparks between her and Shkreli, but now, she gave them air. She thought about when he’d teased her about being a nerd in an old photo he glimpsed, and how she felt when he added her to his visitors’ list (he’s not a big fan of visitors, but wanted her to come). A realization hit her. In the visitors’ room, “I told Martin I loved him,” Smythe says. “And he told me he loved me, too.” She asked if she could kiss him, and he said yes. The room smelled of chicken wings, she remembers.

They couldn’t touch beyond a chaste hug and kiss, per prison rules, and have never slept together, but the relationship moved forward through continued visits, phone calls, and emails. “It’s hard to think of a time when I felt happier,” Smythe says. “At first he’s like, ‘Can I call you my girlfriend?’ ” she says, and “this led very naturally into thinking about a future together.” Soon they were discussing their kids’ names and prenups. After Smythe worried about being too old to have children when Shkreli got out of prison, he suggested she freeze her eggs. She did so last spring. Rita Cushenberry, who befriended Smythe while visiting her own boyfriend in prison, observed Smythe and Shkreli together there. “He has the biggest, warmest smile ever,” she says, and “it was a beautiful thing to see how her eyes would just light up.”

When Smythe told her family about the relationship, her brother Michael says he and their parents were “stunned,” but Smythe seemed “significantly happier.” “She can handle it,” says Alyssa Haak, a friend who met Smythe in college. “She fully knows what she’s quote-unquote getting into.” Smythe says she’s considered the downsides of life with someone as infamous as Shkreli and is undeterred. “I’m expecting it to be messy and difficult,” she says.

Each time she visited Shkreli, Smythe became increasingly attuned to the indignities of life in prison. “It gave me a tiny, tiny glimpse of the emotional trauma of incarceration,” she says. Smythe wrote stories on Medium arguing that the sentences of two prisoners Shkreli had become friendly with, Daniel Egipciaco and Charles Tanner, were unfair. (Both were later released, Egipciaco with a sentence reduction and Tanner through clemency.) Now Smythe is rethinking the legal stories she used to write. “You’re never getting the defendant’s side,” she says. Hearing Shkreli’s perspective throughout the trial and watching his experience in prison has “changed my perspective enormously,” she says. “I start to sound like a defense lawyer when I talk now.”

She sold movie rights to her book proposal last year, although the book itself hasn’t been bought, for a small sum. She now works remotely for a journalism start-up, where her boss is aware of her relationship with Shkreli. Because COVID safety protocols have ended most prison visits, Smythe hasn’t seen Shkreli since February 2020. In April, when he asked for early release because of coronavirus spread inside prisons, Smythe wrote a letter, which he approved, describing their commitment and proposing he live with her. (Though his lawyers called her his fiancée in their own request for early release, Smythe says she and Shkreli are actually “life partners.”)

When Shkreli found out about this article, though, he stopped communicating with her. He didn’t want her telling her story, she says. Smythe thinks it’s because he’s worried about fallout for her. While she waits to hear from him, she monitors Google Alerts for his name, posts in support groups for loved ones of inmates, and—because inmates must place outgoing calls and can’t accept incoming ones—hopes one day he will call or reply to one of her emails. “It’s completely out of her control,” Haak says; all she can do is “sit around and wait and hope.”

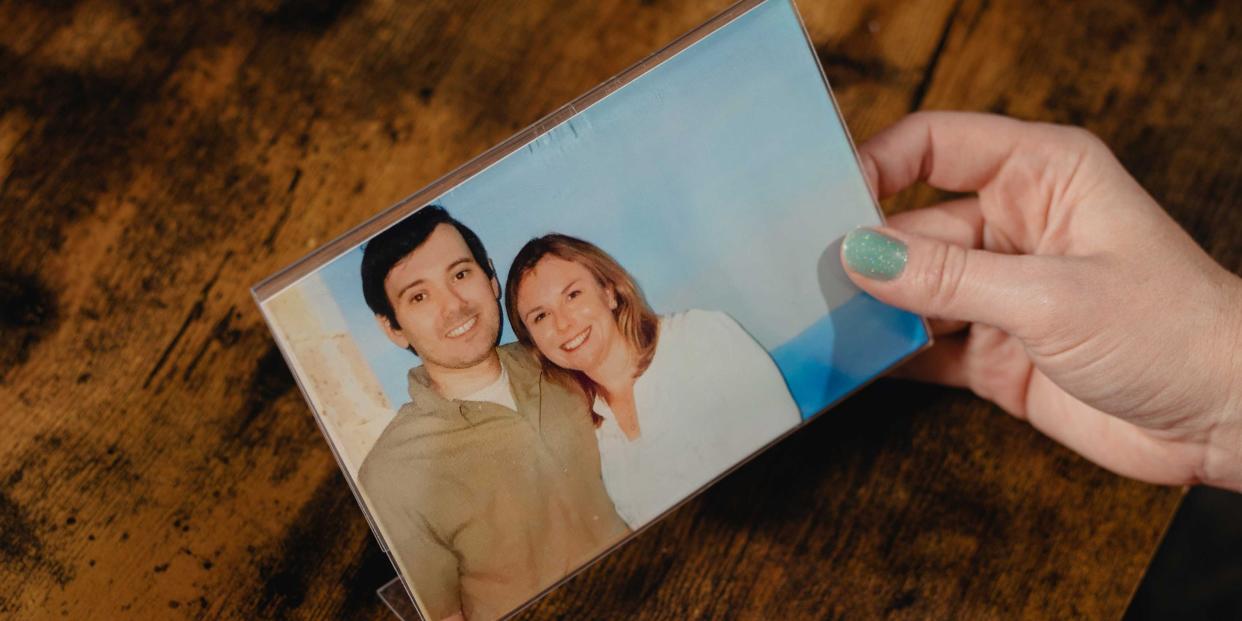

Smythe has only one photo of the two of them, propped next to her bed. Shkreli, his arm around Smythe, has a wide-open smile. “Doesn’t he look human there?” Smythe says, laughing. Cushenberry made a blanket for Smythe with the photo on it, with a caption that reads, “All my better days are the ones spent with you.” I tell Smythe I’ll need to ask Shkreli for comment. “Maybe this will be a reason for him to reach out to me,” she says. Later, when I relay Shkreli’s statement—“Mr. Shkreli wishes Ms. Smythe the best of luck in her future endeavors”—to Smythe via video chat, she says, “That’s sweet,” quietly, not convincingly.

I can’t gauge Shkreli’s motive, and ask Smythe what she thinks. “That’s him saying, You’re going to live your life and we’re just not gonna be together. That I’m going to maybe get my book and that our paths will”—she sighs—“will fork.” She tears up, and I think about what her journalism professor said, about everyone having an agenda. Watching Smythe, I finally realize her motive for telling her story. She wants Shkreli, and hopes putting their love on the record might at last give her some power in the relationship. “He bounces between this delight in having a future life together and this fatalism about how it will never work,” Smythe says. “It’s definitely in the latter category now.” Sitting in her basement apartment, her eyes wet, her voice quavering, she says she will continue to wait for him while he serves the remaining years of his sentence: “I’m gonna try,” she says. “I’ll be here.”

This story appears in the March 2021 issue.

You Might Also Like