The New Jordan Trail: Hiking From Dana to Petra

The town offers an orchestra of acoustics within its frame, and it’s easy to picture the hum of life that must have filled Little Petra’s temples and its famed painted house, a biclinium with one of the only known interiors still decorated in Nabatean paintings. I exit the narrow gap to glimpse the outskirts of Petra and Wadi Musa, the latter harboring a spring where Moses is believed to have quenched his thirst. To this day, the water is still considered holy.

The trial takes more than 40 days to complete, touches four biospheres, 52 villages, and is split into eight sections, a route both the Romans and Nabatean architects of Petra used for trade.

The six-day route from Dana to Petra is one of the most popular portions of the trail. Crossing the region’s molten ridges, undulating valleys, and sandstone mountains, it’s in these insular pockets of Jordan where I begin to learn about the country’s reverential history.

It spans the rise and fall of the some of the world’s most prolific empires, yet it’s brimming with cultural traditions as vibrant today as they were centuries ago.

Bird calls echo in the distance as I sink lower into the wadi, the Arabic word for valley, leaving the plateau where Dana Guesthouse resides. Shrubs dot the vertical rock walls, the only point of reference amid a sea of stone. Oleander is a signifier of water, I learn, as the plant’s salmon blossoms begin to fill our path. But as beautiful as they are, they’re funnel-shaped petals are poisonous; it’s best to keep a distance. “If you fall asleep near one, you may not wake up,” laughs Ayman.

Running exclusively on solar power, Feynan is illuminated by the light of nearly 300 candles. It’s mesmerizing. Refreshed each day, the candles are crafted by a women’s cooperative who live in surrounding Bedouin camps.

Bordering the lodge are some of the world’s oldest copper mines, and the oxidized mineral creates bright pops of green and blue in the gravel. Quarrying of the land first began in the Bronze Age, and during the reign of the Romans, the mines transformed into Christian slave camps; captors were forced to work without the aid of their Achilles tendon.

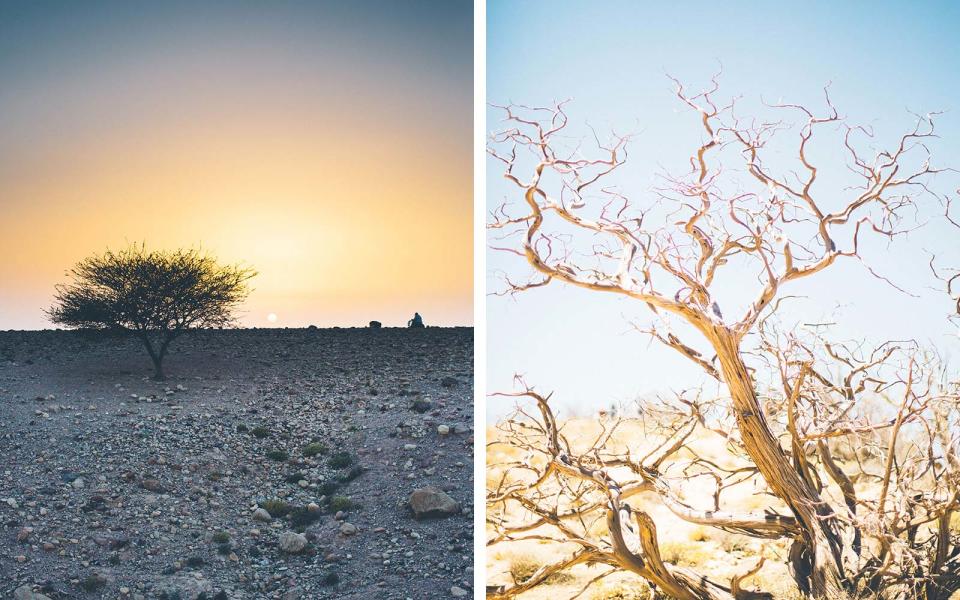

The prosperous trade eliminated the wadi’s tree forest, which was abundant with jujube, juniper, and wild oak trees. Wood was a necessity to smelt copper, and in turn, made Dana one of the most polluted, albeit profitable, places on Earth. Today, the barren area is a paramount point for Christian pilgrimage journeys.

Hiking in southern Jordan means traversing old shepherd routes, the paths used by Bedouin communities to herd goats. Although northern Jordan has a much more established trail system, it’s in these remote passages I find an exhilarating sense of place.

By the day’s end, I reach Wadi Araba. Beyond a silhouette of peaks, I see the lights of Jerusalem dance aglow.

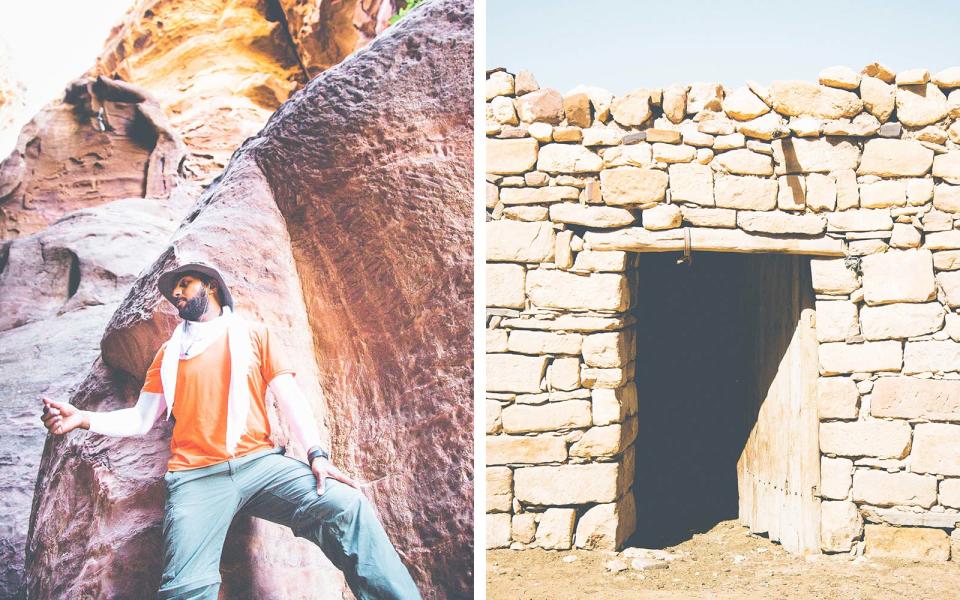

“Meet Marzuk,” says Ayman, as he pets our donkey cargo support. Marzuk is owned by Ali Bdul, who I meet next, a local guide from Petra who is believed to be a direct descendent of the Nabateans. Ali’s here to lead us on our final haul to Petra. His ancestors likely lived in the caves of Petra for centuries.

It was only in 1985 the site stopped being a settlement to gain protected status by UNESCO. Now, only locals like Ali can work in the rose-gold city.

I grab a barazek – a cookie made from butter, pistachios, and sugar – before I set off on day three of our hike. Scaling a tilted, flat mountain of stone, I trot skyward. Once at the top, I find an amphitheater where plateaus, peaks, and sediments merge; the onyx Sharah Mountains offer a poignant contradiction to a swath of sandstone. Before I descend into a basin of bulbous boulders, I see a former Ottoman Empire military base, now a mere heap of bricks: the perfect point to gaze at Wadi Araba below.

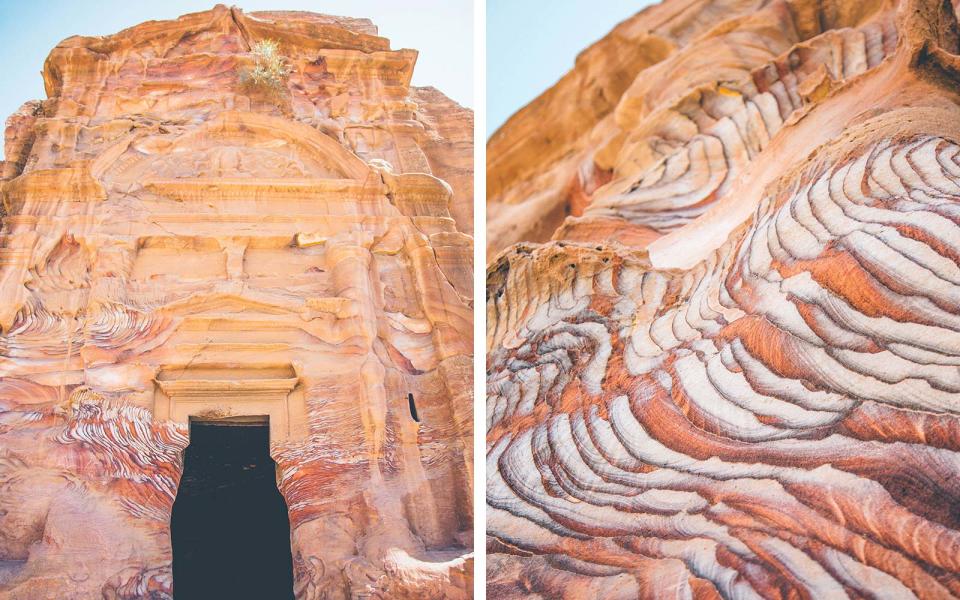

I reach our next camp by 4 p.m., the sun already at a friendlier, cooler tilt. Our neon green tents are set below sandstone towers. Small caverns called tafoni form in pitted circles, marking the entrance to hollow caves, some of which harbor hyenas. The camel and rusted hues of the stone roll into one another; during other instances, they swirl.

A water-influenced phenomenon known as liesegang bedding caused the sediments to curl in such intricately ringed patterns. It’s as if the entire scene melted then froze, instantaneously locking in a diffusion of colors and callouses for mankind to marvel.

“Sabah al-khair,” says Ayman, bidding me good morning. A smile adorns his face, as today is a joyous day; today we reach Petra. Our hike begins out of Gbour Wehdat. Remnants of the ancient Nabateans slowly begin to appear. A bevy of towering gorges reveal where the ancient civilization chiseled wells and aqueducts into a series of monoliths, allowing them to store water for year-round use.

Due to erosion, the aqueduct’s outward-facing lip is now receded, but the excellence of Nabatean craftsmanship remains. The carvers originally established Petra, which aptly translates to stone in Greek, as a religious burial site and began boring the city into stone in the 4th century B.C. Construction didn’t subside until the 2nd century A.D., and in the centuries following, Petra quietly slipped into obscurity. It wasn’t until 1812 that Petra was once again on the world’s stage.

Beyond the canyons is an ancient wine press circled by oleander trees. Wine was integral to Nabatean religious customs, as they believed the fermented grapes brought them closer to the gods. Beyond the press, I meet a Bedouin family: three little girls, one boy, and their grandmother.

The latter has a wooden cane, copper in color, and a necklace made of cloves replete with multiple tiers and silver notches. Cloves help clean her teeth, she tells me, as she fiddles with four silver rings encasing her fingers. Her grandchildren are holding dried yogurt balls, which they offer me: a delicacy consumed once dropped and melted in boiling water.

I continue to an opening where the Tomb of Aaron is visible. The resting place of prophet Moses’ brother is set atop the peak, the highest mountain in Petra, marking a permanent pillar to the horizon since the early 14th century when the tomb was transferred here from Mount Sinai in Egypt. Holding significance for many world religions, Jordan is the only country the prophets of Islam, Judaism, and Christianity – Mohammed, Moses, and Jesus – are thought to have traversed.

Before entering Petra proper, I scramble up a narrow, sandstone corridor to Siq al-Barid, or Little Petra. At the entrance, a Bedouin man plays a haunting tune on a rababah, an instrument lathered in horse hair and made by stretching the stomach of a goat. Nearby, a boy named Mohammad begins singing a song called da heya, a peaceful greeting for travelers entering the site.

The Nabateans created Little Petra as a caravan town, Ayman tells me; it was formed to host the myriad of traders who ventured to Petra for commerce. Nabateans are believed to have practiced idolatry. Empty square shrines fill the site where their statues once rested, but even in its golden era, some were left empty. When traders visited the Nabateans, they brought their own religious relics to display. Nabateans respected their gods, too.

In awe, I see a multitude of caves in the corridor. In contrast to Petra, almost no sunlight reaches the 1,000-foot alley. On both sides, stairs are carved into stone; they taper off with no foreseeable destination other than the sky itself.

“When you put this on, it's like putting on a tie,” says Ayman, as he lifts an agal, the rope used to tie the iconic shmagh – the red and white scarf of Jordan - in place. I’m stopped at a shop just before the back entrance of Petra; in typical fashion, I agree to a local’s offering of mint tea. The herb permeates the Bedouin shop as I browse through old coins and take cautious sips of the brew, careful not to burn my tongue. Although the tea is sweet and the shop is rich, my mind is on what lies ahead.

“Back to civilization,” says Ayman, as I slowly begin to see a crowd of people: a first. Beyond a stone staircase is Petra’s Monastery, the purported prize of the Dana to Petra hike. Atop the hike’s final slope, I pass a famed sinai agama, a turquoise-blue lizard, before glimpsing the Monastery’s iconic funerary urn, marking the highest point of the two-story wonder.

Although the grand reveal awaits, I find the most meaningful moments of the journey have passed. It’s in the remote lands of Jordan’s backcountry where I discover a multitude of truths. To know a Jordanian is to love them; the soul-penetrating smiles from locals are infectious and warm.

To walk past a Bedouin tent is to be asked if you would like tea, an elixir so potently sweet and endearing; there's no other answer you wish to say than yes. And to visit this country is to visit historic majesty on a scale almost incomprehensible, a place steeped in soul and mystery; it's all but impossible to crave more.

The newly opened trail extends from the Fertile Crescent in the north, to the Arabian Desert and the Red Sea in the south.