Jared Leto Conquered Age, Gravity, and Hollywood.

Every morning I drink a gallon of salt water. Say that in the article,” Jared Leto says. “And then everyone’s gonna drink a gallon of salt water in the morning, which unfortunately will make people shit their pants.”

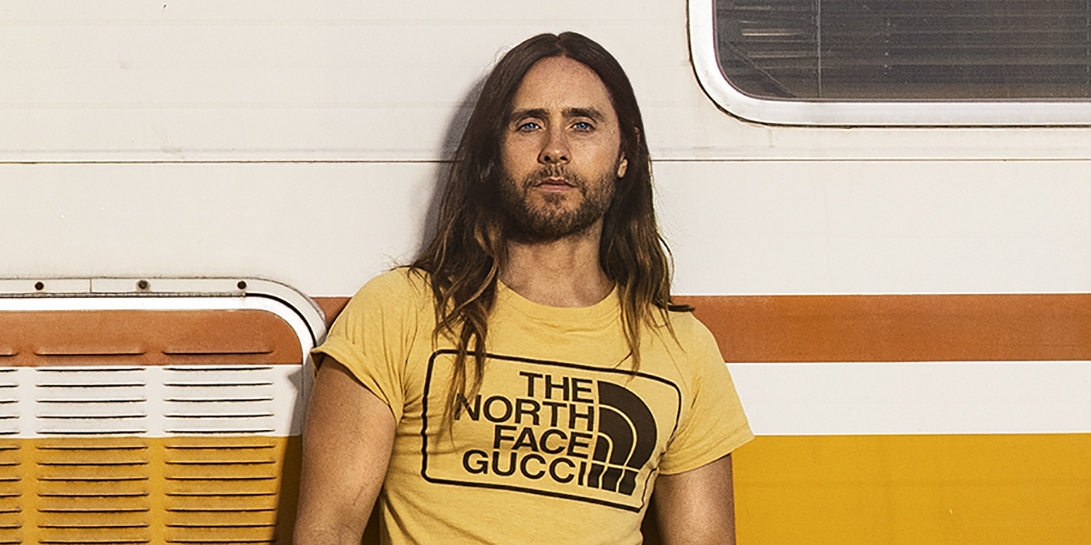

He doesn’t, and you shouldn’t. Leto, allegedly 50, won’t share why he looks so young. “I do have a good answer for that, but I probably won’t tell you,” he says, noting that genetics surely plays a role—his mother has always looked young and healthy. “Just to keep everybody guessing. Really, honestly, at the end of the day, it doesn’t really matter.”

It does matter to a certain writer, who spends a significant sum on injectables each year and who is currently mystified by the face before her. It’s challenging to write about a celebrity’s skin without evoking The Silence of the Lambs, but Leto’s face is healthy looking and apparently lineless. It would be hyperbolic to say it’s the skin of Jordan Catalano, the teen heartthrob he played on My So-Called Life in 1994, but it’s at least the skin of a 30-year-old who wears hats all the time.

Actually, Leto does seem to appreciate a good hat. In the five-part climbing docuseries he made in 2016, Great Wide Open, he often has a big straw number dangling from a strap around his neck, like a maiden in a meadow in a strong breeze. Maybe everyone was right about sun protection.

Another theory about his youthful visage: Leto doesn’t emote very much in casual conversation. He’s certainly capable of flamboyant expression, as when he played Paolo Gucci in last year’s House of Gucci. In that film, Leto has a significant Hitchcockian forehead and brow as well as a prosthetic nose and jowls, deployed to great effect. The juxtaposition of that character’s showiness and the actor’s stillness is jarring, like watching a famous comedian give a somber eulogy. But in our interview, his eyes, light blue and close together, are fixed. His hands fiddle with the cap of a large Acqua Panna water bottle, ripping out the lid’s plastic innards. Yet his face is very still. Between the calm intensity and the shoulder-length hair parted neatly to one side, talking to Leto is a bit like how I imagine interviewing a cult leader would be. While disconcerting to this interlocutor, his affect might also prevent the formation of fine lines.

“People started talking about my age and that sort of thing ten years ago,” he says. “As you get older, people start saying, ‘Ah, you’re still young.’ And then there’s this age where they go, Really? ” He concedes that it’s always nice to hear and he doesn’t mind talking about it, but again, he adds, it doesn’t really matter.

It’s what’s on the inside that counts, he tells me earnestly, then continues less earnestly. “Unfortunately, I’m not getting movie roles where I play, like, ‘a rather young-looking old man.’ Maybe I’m doing something wrong—not taking advantage of it enough. It just doesn’t matter. You can be 30 years old and live an amazingly exciting, interesting, fulfilling life, or you can be 60 and having a crisis.”

IF LETO IS NOT fulfilled, we’re all toast. In an era when many celebrities are multihyphenates, leveraging their platforms to dabble in several industries, Leto is a maxihyphenate. He is primarily known as an actor, and he won an Oscar in 2014 for his role in Dallas Buyers Club. But the rock band he formed in 1988 with his brother Shannon, Thirty Seconds to Mars, is a real band: The brothers have released five albums, selling more than 15 million copies. And Leto, who began climbing himself after making Great Wide Open, is a real climber, with designs on El Capitan in Yosemite. He doesn’t seem to half-ass anything he does. “Jared is uniquely talented and brilliant, all while being kind and humble,” his friend Evan Spiegel, the cofounder and CEO of Snapchat, emails, adding, “Few people realize what a successful

tech investor he has been over the years.” (Leto invested in Airbnb, Uber, and Spotify.)

Leto appears self-aware about being intimidating, and the humility Spiegel refers to seems almost compulsive—he defuses that intimidating persona whenever possible. As our Zoom call begins, for instance, Leto shuffles into the frame still buttoning his red flannel shirt. The slice of room behind him during the call, in a house in Nevada, is as neutered of personality as a celebrity’s space can be: The ceiling is white and the walls are beige; nothing else is visible. Still, his mastery of various verticals—when free-solo demon Alex Honnold asked him why he’d waited so long to start climbing, Leto told him he’d been “busy climbing other mountains”—can be toxically humbling to consider.

He points out that a lot of people do a lot of different things, but very few are so committed to advancing in such a pupu platter of them. He explains that he simply does whatever he is compelled beyond a reasonable doubt to do. For a few years, he made “no new projects” a New Year’s resolution, hoping to focus on the ones already before him. He attributes his capacity for hobbies and second and third careers in part to a commitment to, or maybe more of a mania about, protecting his time. He dislikes and avoids small talk, for instance, finding deeper conversations more productive.

Leto opted to conduct our interview virtually, because he couldn’t risk being sidetracked from his upcoming commitments by a Covid-19 quarantine. He’s preparing to start global press tours for both WeCrashed (debuting March 18 on Apple TV+), a romance-biopic miniseries in which he plays disgraced WeWork CEO Adam Neumann, and the film Morbius (out April 1), in which he plays a biochemist who, in an attempt to heal his own rare blood disease, turns himself into a vampiric monster-slash-hero.

“I’m impatient, and I guard my time really well,” he says. “And that’s probably why I’m able to do multiple things and achieve some of my goals with those things.” Soothingly, for those of us who have a lot of difficulty juggling opportunities, Leto wasn’t always able to do this so confidently. He had to accept that when you say yes to one thing, you’re always saying no to something else.

“If you want to achieve greatly, I can tell you how, but it may not be what you want,” he says, then delivers another long caveat that there are many high-achieving people out there, so he’s not speaking from a place of superiority. “I’ve worked really, really hard and I’ve achieved some goals in my life, and it’s been a beautiful thing. But there’s a price you pay for all of it. It just depends how important those goals are to you.”

But sometimes you can say yes to two beautiful things at once. Leto made Great Wide Open, for instance, partly because he figured filming a series about climbers was the best way to carve out the time required to learn to climb. The project also gave him the unique opportunity to observe, firsthand, some of the most impressive climbers; he learned by simul-climbing behind Alex Honnold and by getting tossed off a cliff by Tommy Caldwell. Seven years later, Leto has become a serious multi-pitch climber. He climbs in Joshua Tree, Yosemite, Red Rock Canyon in Nevada, and even Sardinia.

From a fitness perspective, he compares climbing to touring with Thirty Seconds to Mars (Leto is lead vocalist and plays the guitar, bass, and keyboards), which he says is still the most physically demanding thing he’s ever done in his life. “I’d put it somewhere between amateur bowling and . . . Usain Bolt,” he says. “It’s hard to explain because you’re up there having a good time, but it’s full on for a couple of hours. You’re singing and running around, you have so much adrenaline, and you’re performing at your limit. Your heart is pounding outta your chest, you’re dripping sweat, and you’re exhilarated, but you’re working your body in a really intense way.”

I ask whether he appreciates climbing because you’re so often isolated, which must be refreshing for someone who frequently receives so much attention when he’s out and about. No, he clarifies, he doesn’t climb as an escape from fame, though he does enjoy that many of the areas where he likes to climb have no cell service. And to climb, the weather typically has to be good. So he’s out there on a beautiful day, with a clear objective, severed from “the digital leash,” doing something physical.

Climbing is less an escape from being Jared Leto than it is the zenith of being Jared Leto.

LETO DRAWS A LINE between his approach to climbing—sustained, immersive—and his approach to acting. He’s gained a reputation as a Method actor; he reportedly terrorized his costars while he was playing the Joker in 2016’s Suicide Squad, allegedly sending them used condoms, anal beads, and even a rat.

He selects roles that lend themselves to over-the-top performances. His acting can have a caricatural quality, as can his public appearances. The 2019 Met Gala’s “camp” theme felt particularly well suited to Leto, who carried a replica of his own head on the red carpet. Audiences have been baffled by his extravagance in the past. But even those who aren’t necessarily fans of his high-intensity performance style admit to being transfixed. As one writer noted in an end-of-year Leto-spective for The Ringer, evaluating his performances in The Little Things, House of Gucci, and Justice League, “It finally feels like he’s in on the joke rather than the butt of one. Leto’s year in movies has turned him from an actor everyone loves to hate into an actor everyone hates but nevertheless loves to watch.”

His role in WeCrashed is quieter. He peers around—with brown eyes, thanks to contacts—with an alien’s remoteness and wonder. His aesthetic transformation for that role was much subtler than for Paolo Gucci, who looks like an old-timey Russian oligarch, but his acting in WeCrashed is as jarring.

I ask whether he ever feels ridiculous—thinking how self-conscious I would feel depicting a person who is still alive and who may see my performance. “I never feel ridiculous about that. I don’t think I would take on the job if I had any indication that that would be the case,” he says. Once he takes a role, he commits to it fully.

On set, Anne Hathaway, who plays Neumann’s wife, Rebekah, felt odd calling him “Jared” and instead just referred to him as “Adam” or “my costar.” “I am aware that sort of thing can be badly misunderstood if you don’t spend a lot of time with actors, so please allow me to say in the clearest way possible what a pleasure the experience was with whoever-that-was,” says Hathaway. Like Evan Spiegel, she describes Leto as very generous and kind. I like how she articulates Leto’s militant approach to maximizing his time: “It’s hard to put into words how much I learned from being around someone who builds his freedom from his phenomenal discipline and focus.”

Leto went straight from playing Gucci, with a thick Italian accent, to playing Neumann, with a delicate Israeli one. He worried about slipping into the mannerisms of one when he was portraying the other. “But of course,” he qualifies, “neither of these people are ever going to be those people. I’m never going to be Paolo. Your job is to bring to life the spirit of the person that’s depicted in the story, to serve the story.”

Though Leto is known to be very selective about his roles, the through line for those selections is difficult to decipher. What appealing commonality do Morbius and Neumann and Gucci have? Leto says he just hopes he’ll be able to enter a “flow state” with each character—the same state he enters when he’s writing music and it feels right.

Leto says the aesthetic features of his characters are just trappings. “I’m thinking about the heart of the character, the soul, the spirit,” he says. “Those other things—it’s the description.” I start to point out that Leto has made extreme changes to his own physique for roles, gaining and losing significant weight.

“But,” he interjects, “what’s more important is: How does it change the way you walk? How does it change the way you talk? How does it change the way people treat you? I gained over 60 pounds for a role once, and it was amazing. I remember asking someone for the time in New York and they, like, recoiled. I saw people I knew who didn’t know I was filming and thought I had fallen off the—I don’t know how to describe it—that I had ‘not been taking care of myself.’ They took it as a sign of something wrong in my life. It was a really wild thing to experience that.”

Leto feels limited by his own body “all the time,” he says—especially in the climber company he keeps. He mentions that in the past he has “dealt with some serious, years long issues with life-changing, intense levels of pain that have been quite brutal.”

When I ask him to tell me more about this pain, he deploys a very Leto-esque tactic, pivoting to the existential as a way to avoid the personal. “Hold on one second, hold on.” He changes positions slightly. The thread of the conversation momentarily broken, he offers up a recommendation for a book on pain: The Way Out, by Alan Gordon. He’s then lost to a philosophical discussion of the relationship between persistent, mysterious chronic pain and the emotional situation a sufferer might be in. It’s fascinating but impersonal. I ask him if he’s speaking from his own experience or broadly. “Broadly, but I understand that, too,” he says. A second later, he shifts to the stomach. “I don’t know if you know about ulcers,” he says before I have really caught up. And then he’s away again, on a tangent about ulcers: Did you know that they’re caused by a bacteria and not stress as people originally thought?

Later I ask him whether he regrets any roles he’s taken on, and he launches another nuclear defense: the ephemerality of this life. “No. Come on,” he says. “I’m gonna be dead soon. Who gives a flying fuck?”

His disregard for certain pressures of life and career—and, by extension, my questions about them—is a little bit intoxicating. For a few days after we speak, I feel better able to triage the bullshit in my own life: Engaging in the conversation gave me the same sense of control and clarity, however fleeting, as reading a self-help book.

LATER IN THE AFTERNOON, Leto calls me again, this time from an area on the edge of Red Rock Canyon. He appears onscreen wearing broad Gucci sunglasses and a neon-blue Thirty Seconds to Mars T-shirt with a psychedelic skull print under his red flannel.

The afternoon sun is weak through the blanched, leafless trees. It’s Super Bowl Sunday, almost time for kickoff, and the park is empty. This area is about to close—rather early, Leto notes—but he has come here to call before hiking because there is a cell-phone tower nearby. A park ranger, likely eager to get to his game-day plans, approaches and reminds him of the closing time.

Otherwise the spot is very quiet; the only sounds are Leto’s footfalls on the path as he walks and the occasional croaks of desert frogs. “There’s an old historic cabin,” he says, dizzily reorienting his phone until its camera frames a cabin with a stone foundation and wood siding. “This used to be part of the Old Spanish Trail back here, actually—people would pass through on their way west to California to settle.”

The weather is perfect, he says, maybe slightly warmer than 74 degrees. He seems content to stroll, especially because an excursion the day before had been “a little more climbing, a little less walking around in nature.” Today he’s feeling “a little shattered.”

Leto has never been good at resting, but he’s begun to warm to rest as a climber. You can only climb as hard as you rest, he says. When he’s on a climb, he treats breaks as tools. Learning when to take those breaks, he adds, is part of the strategy. “That’s a big thing to come to in life, resting and balance,” he says. And yet, at 50 (again: allegedly), Leto seems very unlikely to slow down. He hates the phrase “slow down,” and also its cousin, “settle down.”

“Why would you ever wanna settle?” he says. He admits that for Olympians who forfeited typical parts of their childhood in pursuit of incredible goals, a conscious decision to slow down may be appropriate when they transition out of their career at a relatively young age. And sure, he continues, “your physical body might give out on you, or your brain, and maybe then you turn away from some objectives and you can turn toward others. You can be a hundred years old and take a very deep, mindful breath. That probably has its own challenges and rewards.”

While he walks, he tells me about the time he came to terms with his imminent death as he began to fall during a climb with Honnold. As he looked up and saw the rope supporting him deteriorating against the rock, he says, “it was like an acceptance, and a little bit of sadness. It wasn’t even fear. It was like, ah, not now.”

He pauses and swings his phone around to show me Mount Wilson, which he plans to climb later in the week. “It probably looks small to you,” he says, but it looks huge and jagged and steep. He notes that the moon is out, then whips me around again to frame the faint white disk in the blue sky.

The park ranger reappears. They’re going to kick Leto out of the park at 3:30, so it’s time for him to move along.

He has nothing but respect for their time.

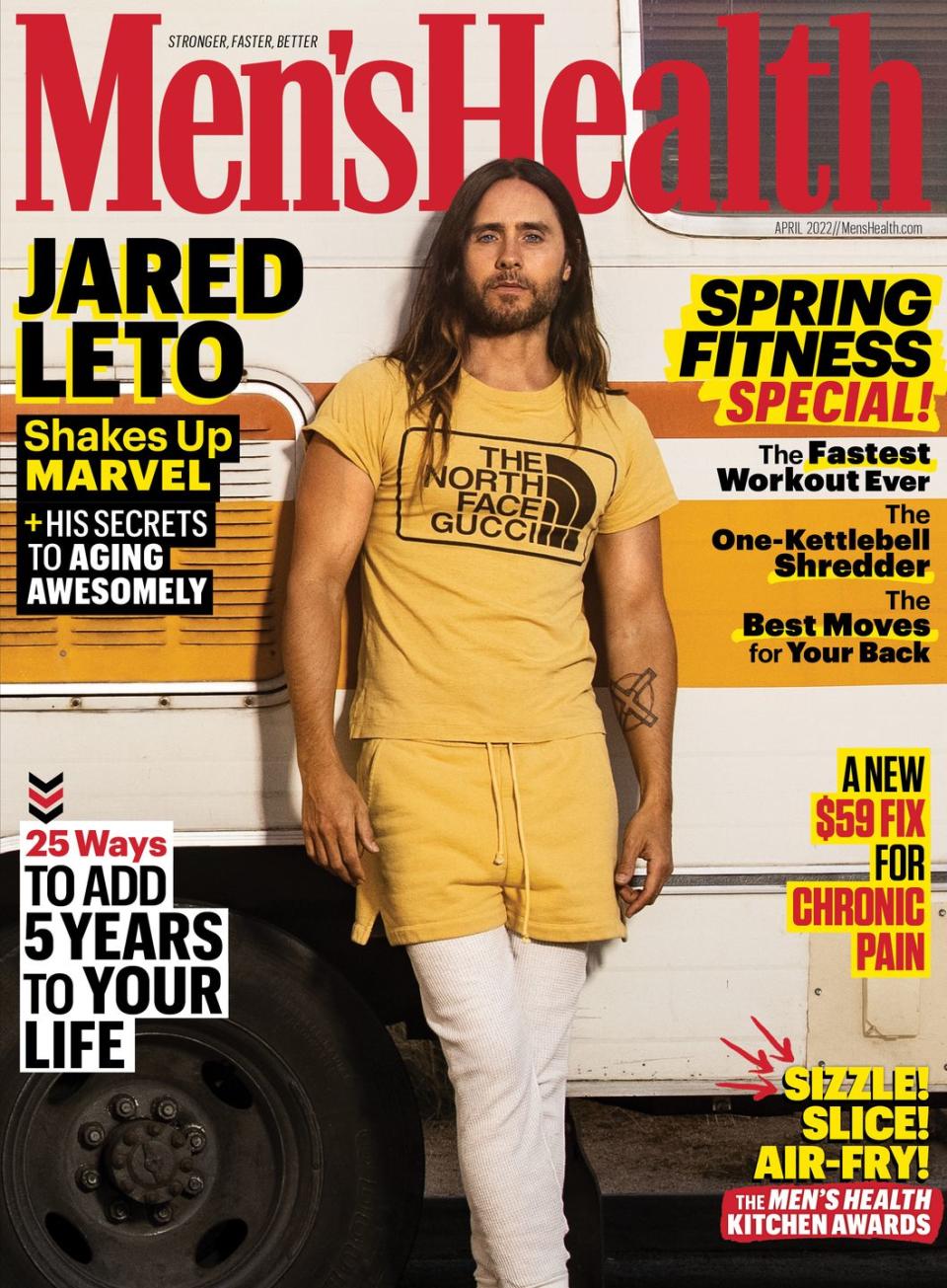

This story appears in the April 2022 issue of Men's Health.

You Might Also Like