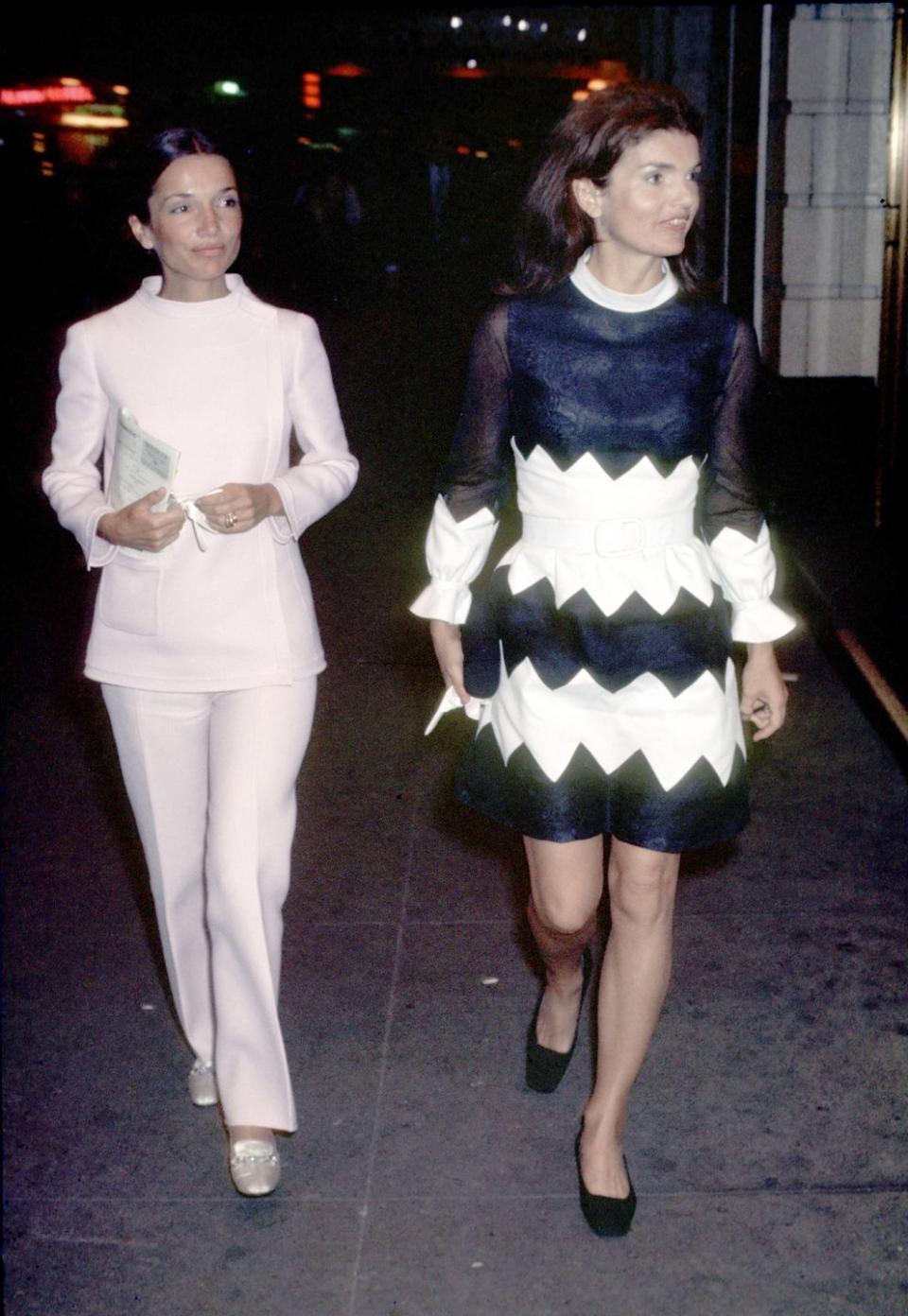

Jackie Kennedy and Lee Radziwill's Second Acts in the 1970s? Careers as a Book Publisher and TV Host

In honor of Lee Radziwill, who passed away on February 15, we're resurfacing this story on her career in the 1970s.

“For the first time, I really feel true to myself,” Lee Radziwill told Judy Klemesrud of the New York Times in a September 1974 interview. Since leaving her marriage to Prince Stanislaw Radziwill, Lee was experiencing a burst of creative activity. Besides going on tour with the Rolling Stones two years earlier, her involvement in documentaries by Jonas Mekas and the Maysles brothers, and trying to write a memoir, Lee had embarked on a television career. If Jackie was finally found, Lee refused to be lost.

Described by Klemesrud as a “society blueblood, ex-princess” and “little sister to one of the world’s most famous women,” Lee swept “into her bright red living room on Fifth Avenue…to talk about her latest endeavor: working.”

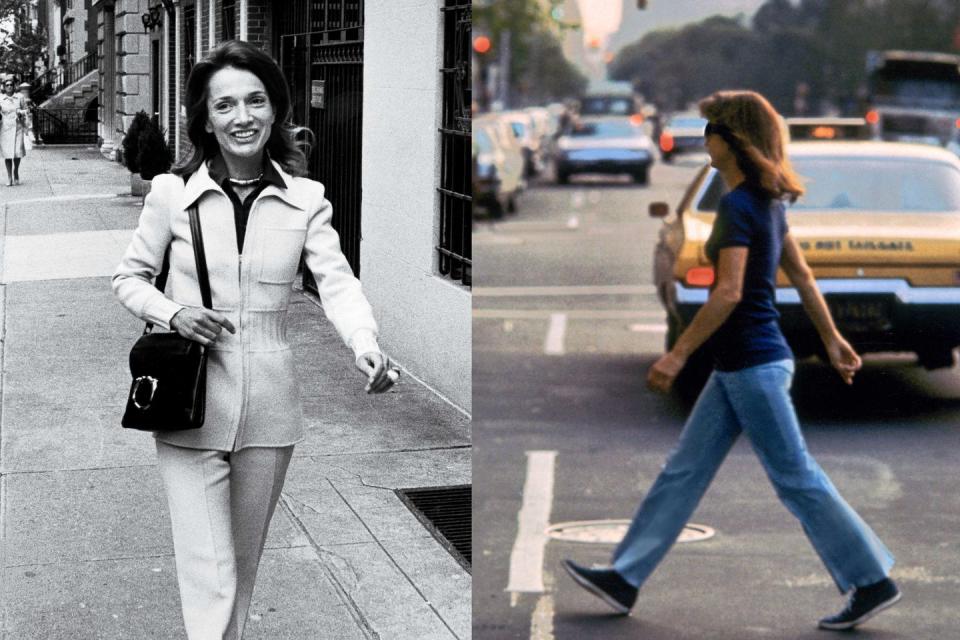

Throughout the 1970s this was how she was often portrayed: a storm looking for a port. Pencil-thin, dressed in a white silk shirt and navy pants, Lee chain-smoked throughout the interview. When Klemesrud asked why someone of her background wanted to “become a working woman,” Lee answered in the parlance of the times: “I’m obviously all for women’s lib, but…this is no classic case of women’s lib. The most important thing, I’ve found, is to be self-reliant. I just felt I was being true to myself by returning to New York and starting a life of my own. In London I found I was no longer able to contribute to anyone else’s life except my children’s, and they’re at an age now where they no longer need me very much.”

Her friend William Paley, founder and chairman of CBS, had agreed to create a pilot of six “Conversations with Lee Radziwill” to be made available to five CBS news programs, with the goal being the development of her own syndicated show. It was Lee’s “dream job,” a half-hour interview show of her own, with one guest at a time.

Lee conducted six interviews, mostly with celebrated friends of hers: John Kenneth Galbraith, Gloria Steinem, Rudolph Nureyev, Halston, Jaws author Peter Benchley, and the Harvard psychiatrist and writer Robert Coles. Nureyev rarely appeared on television, but he could not refuse Lee, nor could the fashion designer Halston.

Lee was often motivated as much by the things she disliked as by the things she admired. She clearly disliked the talk show hosts of the mid-’70s, describing them as “literally offensive. They’re so glib, and have done little homework on their guests’ backgrounds… The one exception is Barbara Walters, who is absolutely great.”

Lee had indeed done her homework, impressing Nureyev with her knowledge of ballet, and she especially came to life in her interview with Halston, displaying her deep appreciation of couture. At one point she asked Halston what a woman could buy with $25. “Nothing,” he said.

Galbraith characterized his interview with Lee as “thoroughly rehearsed spontaneity.” (Lee later described him as “the only man I ever met wearing a nightgown. It was madras with long sleeves, a Moghul idea he got when he was in India.”) When Lee asked Nureyev if he ever planned to get married, the great dancer blushed at the teasing question, but he gave back as good as he got: “One doesn’t expect close friends to ask silly questions.”

Curiously, the most winning of all the conversations was the one Lee was most nervous about because she knew the subject the least: Peter Benchley. She charmed and flirted with the writer, who later admitted that his time with Lee was “one of the most delightful afternoons I ever spent,” describing her as “one of the most charming, solicitous, sweetest women I ever met in my life… She framed interesting questions and was well prepared.”

But Benchley, who was acquainted with the medium, nonetheless felt that Lee was, if anything, too eager to avoid controversy. Seeing the interviews as nothing but “soft news,” most of the local stations turned their backs on Lee’s hard work. The time lag between when the interviews were conducted and when they finally went on the air made them seem out of date, especially in an era when television news was confronting the upheavals of the ’70s counterculture.

But Lee found another way to shine. The year 1974 also saw the publication of One Special Summer by Delacorte Press, with an initial print run of 100,000. On a visit to their childhood home, Merrywood, to see their mother Janet and their stepfather, Jackie and Lee came together and sorted through old diaries, letters, and artifacts stored in the attic. Lee was hoping to use what she found in her ongoing memoir. That’s when the two sisters discovered the sweet, funny, girlish record they had made of their first trip to Europe together in 1951 as a present to their mother. It had survived and was now a testament to how close they had once been.

After some persuading, Lee convinced Jackie, who was still shy about publicly revealing any aspect of herself, that they should publish it, just as it was. Ironically, Jackie’s desire for privacy almost eclipsed her editorial instincts, which would soon be on display when she took a job as an editor at Viking.

After the death of Aristotle Onassis, in March 1975, Jackie returned to the Kennedy compound in Hyannis Port for a brief visit. She felt overwhelmed there by memories of her life with Jack. “This was the only house where we really lived, where we had our children, where every little pickle jar I had found in some little country lane on the Cape was placed…and all the memories came before my eyes,” she remembered.

One evening Rose Kennedy invited her to take a walk on the beach, not wanting to leave her alone. “I can’t remember Jack’s voice exactly anymore,” Jackie confided, “but I still can’t stand to look at pictures of him.”

When she was left alone, she dipped into the works of two of her favorite poets, C.P. Cavafy and George Seferis.Even before her Greek sojourn she had loved these poets, and now the melancholy tone of Seferis’s “The Last Day” spoke to her mood:

"This wind reminds me of spring," said my friend as she walked beside me gazing into the distance, "the spring that came suddenly in the winter by the closed-in sea. So unexpected. So many years have gone…"

When Jackie returned to Manhattan in September, Tish Baldrige, her former secretary and close friend, noticed how listless she seemed. John Jr., 14, was attending the Collegiate School on the Upper West Side, and Caroline, 17, was planning to study art at Sotheby’s in London. They did not need her as much, and Jackie found herself at loose ends. Tish suggested that Jackie consider going to work.

“Who, me? Work?” Jackie had joked, but she immediately warmed to the idea. Tish, no longer her secretary but still her friend, and now the head of a Manhattan public relations firm, later told the New York Times, “I really felt she needed something to get out in the world and meet people doing interesting things, use that energy and that good brain of hers. I suggested publishing. Viking was my publisher, and I said to her, ‘Look, you know Tommy Guinzburg. Why don’t you talk to him?’”

Jackie arranged a lunch at Le Perigord, on East 52nd Street, with Guinzburg, Viking’s publisher, whom she had met years earlier through George Plimpton. It was not lost on Guinzburg that Jackie would be of inestimable value to any publishing house, given the cachet that her name would bring. “What author could not be lured to Viking by the promise of having Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy Onassis as his or her editor?” Christopher Andersen, one of Jackie’s chroniclers, commented. Guinzburg also felt that if Jackie ever decided to write a memoir, he would be there “to catch the bouquet.”

Jackie was offered a part-time job working four days a week as a consulting editor at a yearly salary of $10,000. Obviously not needing the money after her $26 million settlement from the Onassis estate, she accepted.

In the second week of September 1975, Jackie showed up at Viking’s office at 625 Madison Avenue to begin work, the first paying job she had taken in 22 years. Despite the fans crowding the lobby of Viking’s offices trying to get a glimpse of her, Jackie quickly made it apparent to her co-workers that she did not expect special treatment. She settled into her small office and was seen making pots of coffee for her colleagues. She also did her own typing, filing, and phone-calling.

“I expect to be learning the ropes at first,” she told reporters. “Like everybody else, I have to work my way up to an office with a window.” As much as she tried to fit into the editorial corps at Viking, there was no escaping her off-the-charts fame. No sooner had she begun working than renowned Life photographer Alfred Eisenstaedt was sent by the magazine to photograph Jackie in her new job.

Two of the books she edited for Viking reflected her interest in czarist Russia, which she shared with Lee: In the Russian Style, in 1976, and Boris Zvorykin’s The Firebird and Other Russian Fairy Tales, in 1978. Through her friendship with Andreas Brown, owner of the Gotham Book Mart, Jackie was introduced to the work of Zvorykin, the Russian artist and illustrator, and as an editor at Viking she was able to bring out a new edition of his illustrated collection.

Three years later Jackie would have another occasion to express her admiration of Russian artists. In December 1981, the poet and Nobel laureate Czeslaw Milosz was invited to be the guest of honor at a dinner held for patrons of Poets & Writers, the -nonprofit -organization devoted to the literary arts, but when Milosz bowed out, the development director at the time, Eva Burch, suggested replacing him with the émigré Russian poet Joseph Brodsky.

As this was five years before Brodsky himself would be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, there was concern that he was not well known enough to the assembled guests. Burch suggested that Mikhail Baryshnikov-a close friend of Brodsky’s-co-host the evening. So it was arranged and held at the home of investment banker and poet William Kistler, who lived at 1040 Fifth Avenue, Jackie’s building. Guests included Susan Sontag, Michael and Alice Arlen, David Rose, Timothy Seldes, the Arthur Schlesingers-and Jackie Onassis.

Everyone arrived before the guest of honor, and they were all dressed to the nines (except for Sontag, who wasn’t, and Brodsky and Baryshnikov, who arrived together in corduroys and jeans). Jackie appeared resplendent in a black-sashed red tunic and black wide-leg silk pants, looking for all the world like a Cossack.

As soon as Brodsky walked through the door, Jackie stood up and said as loudly as her whispery voice would allow, “I can’t believe I’m meeting you at last! Is it going to be as it’s been in my dreams?”

Abashed, Brodsky turned red and mumbled, “I hope we have a chance to talk later,” before spinning off to the bar for a glass of whiskey. When it came time to be seated for dinner, Jackie found herself across from the Russian poet, instead of at his side, at a table so wide that it made conversation difficult. Things got more awkward when the guest next to Brodsky told him he had the profile of Napoleon. Brodsky suddenly jumped up and left the table. Baryshnikov and Sontag followed him out of the room, and out of the party.

After he left, Jackie stayed a while longer, smoothing things over by telling Kistler, “Russians are so emotional. You should see how Nureyev behaved.”

But she had relished the evening. In Brodsky two realms Jackie admired merged: poetry and Russian culture. Ironically, a decade earlier the American poet Robert Lowell had become obsessed with Jackie during one of his manic phases, writing to her constantly. Perhaps if he had been Russian, she might have written him back.

Adapted with permission from Sam Kashner and Nancy Schoenberger from The Fabulous Bouvier Sisters: The Tragic and Glamorous Lives of Jackie and Lee, published by Harper, September 2018.

This story appears in the September 2018 issue of Town & Country. Subscribe Now

('You Might Also Like',)