In Italy, Family-Run Shoe Factories Are Part of the Culture. What Happens If They Close?

Like so many industries, the COVID-19 pandemic has put the nation's artisanal footwear trade at risk.

A three-hour drive from Rome, through rolling hills and nestled between the Apennine Mountains and the Adriatic Sea, lies the region of Le Marche. With neither the Renaissance legend of Tuscany nor the dense forests of Umbria, Le Marche is quiet and rural, stretching nearly 4,000 square miles across Italy's sandy eastern coast.

However unassuming Le Marche may be, Italy is not quite Italy without it. It has long served as the ancestral home of the country's artisanal shoe trade. Today, it's still dotted with footwear factories of all makes and models, from large-scale facilities employing the better part of entire towns to hole-in-the-wall workshops lining cobblestone streets.

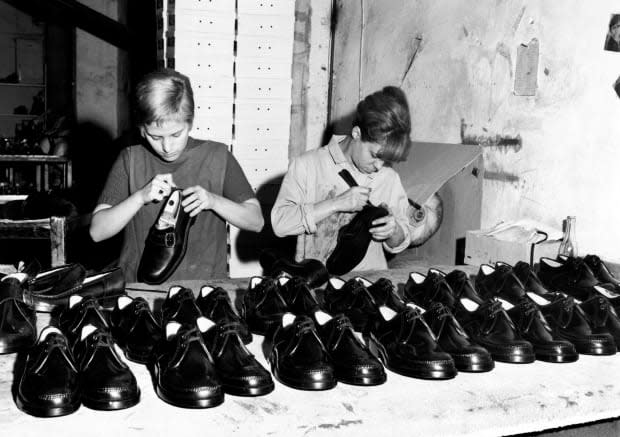

"There's a strong link with the territory," says Matteo Pasca, the director of Arsutoria School, a Milan-based institute for design and technical training in footwear and accessories. "Most of the factories are still small, family-run businesses that hire locally and promote from within. And most of these factories have a tradition of generations that pass the skills from parents to children."

Pasca is speaking from his home in Milan, where he's been in quarantine since Italy first went into lockdown in early March. The coronavirus crisis has grasped a particularly strong hold on the country, which, at press time, had seen more than 221,000 total confirmed cases and 30,000 deaths.

In a global pandemic, a craft-based service like shoe production is not exactly the focal point of a nation's fighting efforts to combat such a vicious virus. But these factories are not to be overlooked, and the current climate has threatened to dismantle them altogether.

Seventy-five miles up the coast from Le Marche sits San Mauro Pascoli, a commune that began establishing itself as the regional capital of high-end women's shoe manufacturing as early as the 1830s. So many civilians once worked as cobblers that in 1901, the shoemaking community was granted its own state flag. Here, footwear is not just of economic interest.

"It's a cultural thing, in a lot of respects," says Lauren Bucquet, founder of designer shoe label Labucq, which is made in Italy. "It's much more accepted to follow in your family's footsteps than it is in the U.S. where, when I grew up, I was ready to set my own path and move to New York City. I wasn't interested in doing what my parents did whereas in Italy, it's more culturally accepted, and almost expected, that you go into the family business."

Bucquet launched Labucq in 2018 after a decade-long tenure at Rag & Bone, where she worked directly with factories across Italy (as well as Portugal, Spain and China) and eventually climbed the ranks to become the brand's Director of Footwear and Accessories. With Labucq, she's partnered with two family-run factories in Tuscany, with her primary of the two dating back to the 1970s. Though still half a century old, it's a relative newcomer as compared to, say, the Magli Shoe Factory, which siblings Marino, Mario and Bruno Magli first opened in 1947.

In her years working with Italian factories, Bucquet has watched as some have evolved, scaled or specified, often when younger generations take over for their elders. Some manufacturers may become even more artisanal; others might pivot to take on more luxury-adjacent clients, like those of a Kering or LVMH.

While operations may have changed in the last century, the players themselves haven't. The industry was built on what Pasca calls a "spider network," with the actual shoe factories themselves at the center while surrounded by separate, independent suppliers.

Related Articles

Workers Who Form the Backbone of the Secondhand Market Are Especially Vulnerable in a Time of Pandemic

For Behind-the-Scenes Shoe Designers, the Glory Is in the Craft

When There Are No Red Carpets, What's a Celebrity Stylist to Do?

"You have an ecosystem that works together, and some of these companies are very, very small," says Pasca. "You can have a big factory like Prada working with an embroidery company of maybe 10 people. So you have this strange mix of very teeny companies working for very big brands."

It's already a delicate web, and under certain circumstances, it can very easily fall apart.

When Italy first entered lockdown, some manufacturers had yet to complete production of the Fall 2020 collections. Others had already completed delivery to retailers, but as stores were closing, those products were being sent back. For a system that's only as strong as the sum of its parts, that has posed a significant challenge.

"This industry is very connected," says Pasca. "If the retail stores are suffering, that means that along the chain, the manufacturing will be at risk. The factories already paid for the materials and may not be able to complete production because the retail orders are on hold. A lot depends on what the stores will do with the orders."

Some factories have received outright cancellations from larger-scale retailers. Others, like those with which Lacbuq has partnered, have asked that any outstanding orders be put on hold until facilities can reopen in full. This allows for brands themselves to hedge their bets and not overproduce inventory they might not need. But it also puts the manufacturers in a difficult position, having already purchased supplies for which they may not immediately turn a profit.

"They're obviously not going to force anyone to produce products that are going to put a brand in a worse financial position," says Bucquet, whose primary factory in Tuscany remains financially stable enough to be flexible with its clients. "They're holding steady and waiting to see how things pan out over the next two months as the economy slowly starts to reopen."

The reopening is already in progress. On Monday, May 4, Italy's Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte enacted a gradual plan enabling factories to resume production in phases. Right now, sanitation, not order fulfillment, is the top priority.

"Everybody is working on safety procedures, documentation and protocols," says Pasca. "We need to make sure workers can be in a safe environment without spreading the virus once they get back to the factories. It's really important because we know this situation will last a long time."

With the Fall 2020 footwear and accessories collections already in limbo, factories are approaching upcoming seasons with a realistic degree of skepticism. Most of the annual fairs or trade shows slated for the summer — like Lineapelle, Italy's leading leather fair, held in Milan — have been postponed.

Pasca believes the Spring 2021 fashion weeks, too, will be canceled or in the absolute best of scenarios, held online. This would only further necessitate support from manufacturers' larger clients, including the plush luxury houses that don't own or operate their own factories in the region.

"This will be not only an economic problem," says Pasca. "But the big brands and retailers should take the risk together with their small manufacturers because otherwise, the real risk is that this network of companies could die."

Some of the smaller factories, those that work with more bootstrapped brands or independent retail partners, may have the option to set up stricter payment terms. That includes generating a letter of credit through a bank that can guarantee financial compensation.

The pandemic also raises questions of the long-term stability of the workers themselves who make up the network — skilled craftspeople who understand just how long to leave a design on a shoe last, for example, because the knowledge has been in their family for generations.

"The Louis Vuittons or the Chanels are pushing to have very high-end products," says Pasca. "To be able to have these high-quality products, you need to have high-quality people making them because this job is really labor-intensive. You cannot substitute the workers with the machines. If you lose the people, you lose the value in the products."

Rosanna Fenili, with whom Bucquet works, has spent decades overseeing quality control in factories all over the Tuscany and Le Marche regions. The industry is so small that Fenili estimates she knows or has partnered with 70% of the artisanal shoe factories in Italy. She returned to work on that May 4 date, and while she's noted an understandable air of concern across the factory system, she's also detected something else: energy.

"It's strange even walking down the street now, so you can imagine how different it is when you go inside a factory," says Fenili. "But there's so much energy. Everyone is smiling. In Italy, there was a really long time that no one was smiling. Everyone was so distant from one another. But now, everyone is happy to go to work. There really is a lot of positivity."

The factories are not yet entirely open for business. Fenili speculates that manufacturing will be up and running by August. By this point, however, factory workers will be cued to take their traditional month-long summer holidays, when much of Europe closes down. But this year, for the first time in 50 years, factories will stay open, and not simply because their businesses are on the line.

"Employees will be happy to work," she says, laughing. "So it really is a revolution!"

Never miss the latest fashion industry news. Sign up for the Fashionista daily newsletter.