How Isaac Asimov’s dark alchemy helped defeat Hitler

In 1942, as war clouds gathered over the world, three of the greatest science writers of their generation joined forces to defeat Hitler and the Empire of Japan. Surface-to-air missiles, space-suits and futuristic battleship defences – at a gizmo-packed laboratory on the outskirts of Philadelphia they brainstormed technologies that could have come from their rocket-fuelled novels.

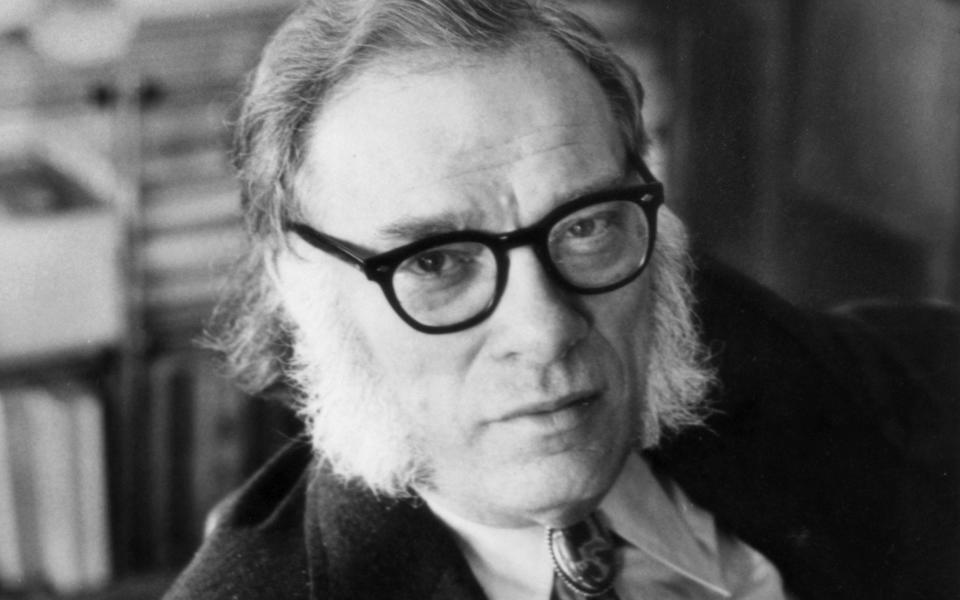

One of the trio was Isaac Asimov. Among the most influential sci-fi authors of all time, Asimov was the author of best-sellers included I, Robot, The Caves of Steel and The Stars Like Dust. He was also one of the first in science fiction to grapple with the concept of artificial intelligence, formulating his “three laws of robotics” (hardwired fail-safes that would ensure robots didn’t go gaga and take over the world).

But if long considered the kingpin of science fiction, his reputation has arguably faded in the past decade or so as his unfussy pulp style and gee-wiz optimism about the future have gone out of fashion. Asimov’s name is once again lit up in stars as a $45 million adaptation of his Foundation saga comes to Apple TV + (though it is telling that the series has been thoroughly eclipsed by Denis Villeneuve’s imminent take on Dune by Frank Herbert, an author regarded as far less significant than Asimov during their lifetimes).

Apple’s Foundation is alas unlikely to fuel as Asimov renaissance. It lacks the wide-eyed charm of the source material and instead serves up a lugubrious Game of Thrones pastiche, with Lee Pace’s villainous Emperor Cleon (who barely features in the novels) bumped up to a grown-up Prince Joffrey. Warning fans of the book, sci-fi website io9 said the show would make Asimov readers want to “tear your TV in two with your bare hands” It isn’t just Asimov devotees who have been left cold. The Telegraph's Benjii Wilson described Foundation as “overblown sci-fi dross”.

But there was nothing dull about what Asimov got up to in Philadelphia. Experimental zero-g suits, technology to intercept Japanese Kamikaze fighters and self-guiding missiles were among the military-industrial breakthroughs Asimov worked on during the war. He did so at the Naval Aviation Experimental Station – an Avengers-style facility at the hulking Philadelphia Naval Shipyard.

There, he collaborated with two other sci-fi giants, Robert Heinlein (Starship Troopers) and L.Sprague de Camp (a star of the pulp era who coined the term “E.T” for extraterrestrial). And though their contribution to the war effort was top secret, who is to say they didn’t help give the Fuhrer a bloody nose?

That, at least, was the version of events put forward Heinlein in a 1986 essay he wrote for an anthology by sci-fi writer Theodore Sturgeon (whom he claimed was likewise recruited by the military). By the author’s telling, those years brainstorming with Asimov and de Camp at the Naval Aviation Experimental Station on the Delaware River in South Philadelphia were full of ceaseless innovation. He further claimed that L.Ron Hubbard, another sci-fi icon and later, the creator of Scientology, assisted the trio in their research.

But military records show Hubbard was actually in Boston at the time, overseeing the conversion of a fishing trawler into a naval patrol vessel. De Camp and Asimov’s recollections of their years at the Naval Aviation Station are meanwhile far less dramatic than Heinlein’s.

De Camp recalled spending weekends with Heinlein. However, he insisted that this was the extent of their interactions. And Asimov look back on his time in Philadelphia as a disaster. Writing to his wife in Brooklyn, he revealed that he constantly feared being fired – so lamentable was his contribution to the war effort (which he stated largely consisted of conducting laborious chemical experiments).

Still, it’s clear Asimov relished the opportunity to bask in the glow of Heinlein’s protean personality. He was slightly in awe of Heinlein – as were most who crossed his path. A charismatic libertine, Heinlein and his wife had an open marriage while both held revolutionary political views which owed more to the free-thinking 1960s than the buttoned-down 1940s.

These opinions could sometimes come across a massively contradictory – and would grow even more so in the years that followed. In 1959 Heinlein published Starship Troopers, a fascistic space opera that argued voting rights should be restricted to those who earned them though martial valour.

Yet just two years later, he wrote Stranger in a Strange Land – a hippy text that advocated free love and universal harmony. He also, in his 1966 novel The Moon is A Harsh Mistress, coined the aphorism, “there’s no such thing as a free lunch”.

All of that was in the future however when, in December 1941, Heinlein turned on the radio to learn the Japanese had bombed Pearl Harbour. Heinlein had qualified as a midshipman at the US Naval Academy at Annapolis in 1925, graduating near the top of his class. Alas, he’d been forced to resign his commission after contracting tuberculosis in 1934 –a blow to his dignity with which he never came to terms.

With war now declared, he was determined to do his bit (prior to his discharge he had served on the USS Lexington, one of the ships sunk by the Japanese). His opportunity arrived when Lieutenant Commander Albert “Buddy” Scoles, in charge of the Aeronautical Materials Laboratory at the Naval Aviation Experimental Station, asked Heinlein to write a piece about the work undertaken at the laboratory, for pulp magazine Astounding Science Fiction.

The Naval Air Experimental Station was a cutting-edge research facility established at the outset of World War I and tasked with developing new technologies of use to the Navy and Air Force. In other words, the perfect environment for a sci-fi writer with a boundless imagination and a firm grasp of science, as Heinlein possessed.

The Astounding piece led to an offer of a permanent position in Philadelphia. This came with the caveat that Heinlein was to be hired as a civilian rather than re-enlisted in the military. He said “yes” anyway and recommended the laboratory recruit two other writers of his acquaintances.

De Camp agreed to come to Philly more or less immediately, though was delayed from joining Heinlein when he fell ill. Asimov, though, had started courting future wife, Gertrude Blugerman – they would marry in the summer of 1942 – and was reluctant to leave New York.

And yet, like many young American men, he heard the patriotic call. And he felt that, as an Ivy League-educated chemist, the Naval Air Experimental Station was where his skills could be best deployed. “I might serve as directly useful for that war effort,’ he reasoned in his 1979 autobiography, In Memory Yet Green. “I knew I could do more as a reasonably capable chemist than as a panicky infantryman, and perhaps the government would think so too.”

The Naval Air Experimental Station was, recalled de Camp, “an awe-inspiring bustle of activity”.

“The ground floor was a huge, open shop,” he wrote, “with gantry cranes rumbling overhead, conducting engine tests (very loud) and structural stress tests.”

Asimov was meanwhile in the process of creating quite a rumble himself. Earlier in 1942 he sat down with his editor John W Campbell in New York for a meeting that would alter the trajectory of science fiction (Heinlein later claimed Campbell was also hired by the military, to help in the development of radar).

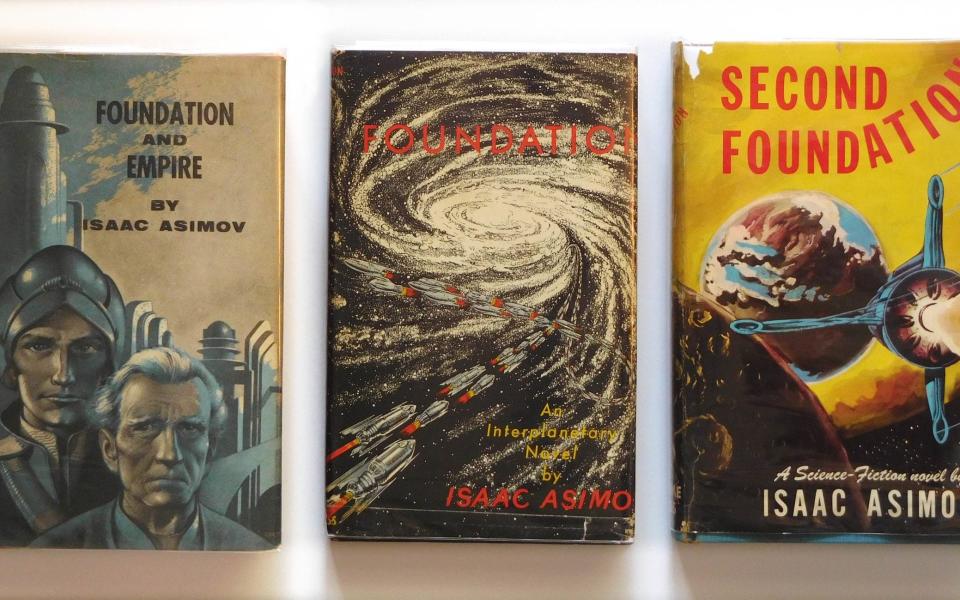

In Campbell’s Astounding offices Asimov set out his vision for a new sci-fi saga. He had in mind a series of linked stories inspired by Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire – but set in a far future Galactic Empire starting to come apart at the seams (Campbell is today a figure of derision in science fiction owing to racist views that included a defence of slavery).

Foundation, first published as a sequence of short stories, brought that vision thrillingly to life. The Empire was crumbling and only one man – pioneering mathematician Hari Seldon – could read the numerical runes and save civilisation.

Asimov was hugely ahead of his time with the idea that rigorous data analysis could predict enormous societal shifts. That is, after all, the dark alchemy by which Google and Facebook anticipate trends and reap millions today. In 1942, Asimov’s belief in the power of algorithms was massively out in front of the curve.

Seldon is portrayed by Jared Harris in the Apple series and, on page and screen, is a hero carved in the image of Asimov himself. He’s bookish, socially awkward – yet unyielding in his defence of logic. Here was a geek who had not just inherited the earth – but could potentially save it too.

Did Heinlein, de Camp and Asimov likewise help save America in 1942? It’s possible we shall never know. Heinlein claimed much of the work was top secret. And de Camp and Asimov never really dwelt on this phase of their lives (Philadelphia receives a fleeting mention in Asimov’s autobiography).

And yet the facts are undeniable – from 1942 until the end of the war, three of the biggest brains in sci-fi were hired by the US military to put their grey matter to work in the struggle against fascism. Once Apple has completed its adaptation of Foundation (which runs to five novels and a number of prequels), it’s a story they might consider bringing to the screen.

Foundation is streaming now on AppleTV+