The International Brigades by Giles Tremlett review: the rag-tag army who took on Franco’s fascists

This is a fine, massively detailed monument to a lost cause. According to the fascist Nationalists – and there is no other kind of nationalist – the Spanish Civil War was a holy war, though far from holy in its prosecution. In reality, it was a despicable Catholic crusade against socialists, communists, anarchists, secularists, -modernists, liberals and unaffiliated adventurers who – despite their common cause and common enemy – were seldom unanimous, and invariably squabbling.

Franco’s Nationalists were more or less monolithic, and disciplined (even if some wore wire necklaces from which hung the ears of their victims). The Spanish army’s troops were loyal to him. They followed orders, as soldiers unquestioningly, unthinkingly do. The Moroccan savages in their ranks raped and mutilated at will: these were not the acts of “rogue” soldiers, but Francoist policy.

The Republicans, on the other hand, were not so much undisciplined as shakily organised. From the very outset, the seeds of fragmentation were discernible, even as they scored important victories. The rabble-rousing Dolores Ibarruri – the fellow traveller’s fellow traveller, known as La Pasionaria or “the Passion Flower” – claimed in the first weeks of the war that the gulf between her gang of Stalinists and the Trotskyists didn’t matter. A few months later, she changed her mind after the two factions enjoyed a bloody war-within-a-war in Barcelona and the Trots were annihilated. The many such sideshows of quasi-tribal and national rivalries, of personal and ideological intolerance, lend a rich density to Tremlett’s account of the Republicans’ International Brigades.

His method has affinities with collage. Numberless strands are interwoven. Although the structure is chronological, it is not sequential. The sources – letters, diaries, interviews, newspapers, memoirs – have determined the shape. Personae disappear, presumed dead, then show up again. Noms de guerre, some of them fanciful, were extraordinarily commonplace. Take Pierre Georges, a teenage brigader who, by 1941, had taken the name of Colonel Fabien, and made one of the first gestures of armed resistance to the German occupation of Paris. (He is commemorated at the metro station of that name.)

The parched landscapes of central Spain brutalised the men who crossed them, hid in them, hatched ambushes in them. They are an unrelenting feature of the book, vividly and pithily described. The fascist sympathiser Sacheverell Sitwell called the central meseta “the most magnificent monotony in the world”. To those who fought there, it must have seemed like a tomb in the guise of an endless cornfield.

Women were scarce. Few got to the front line. They were treated, at best, with disrespect by a cadre of martial misogynists. The bouquets and greetings they received on the “Red Express” from Paris as it passed through station after station to the Spanish border were in contrast to the sort of reception they might receive from the people like the nightmarish André Marty, an ill-tempered paranoiac and sometime naval mutineer turned senior French communist. Like many of his colleagues, he saw spies everywhere. He complained about the quality of recruits, not least those from Lyon whose mayor had slyly dispatched beggars to Spain in an effort to get them off the streets. When Marty formed a new battalion of volunteers hardly off the train, he named it after himself.

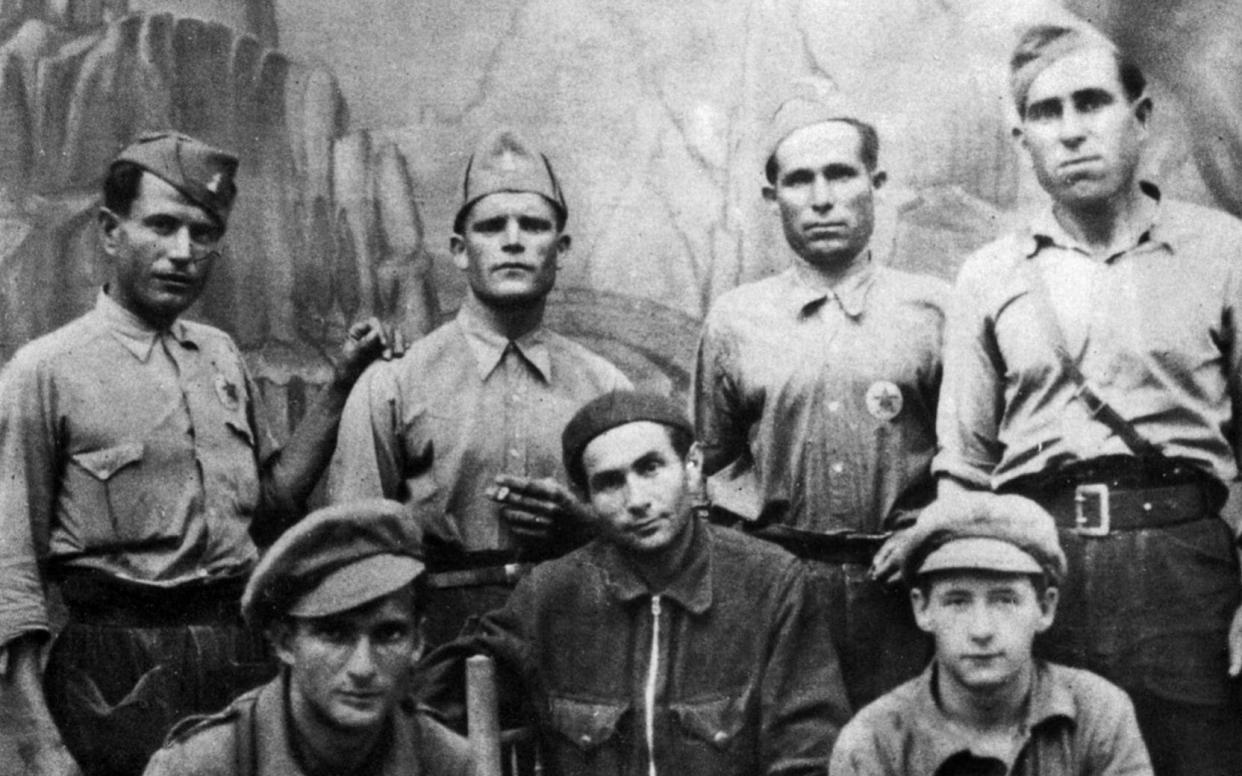

Recruits were sent into battle with no training. One who attempted to load a bullet into his rifle back to front was forced to admit that he had never fired a weapon, “not even in a fairground”. The International Brigades were, of course, not conscripted forces. Nonetheless, all the chaos, barracks humour, disease, lice, filthy latrines, martinets, permanent discomfort, absurdities and pettiness of military life were there: eternal, unchanging, regulation issue.

The Brigaders of Tremlett’s account do not accord with the bogus, death-obsessed “heroes” confected by Ernest Hemingway in his own image. Alvah Bessie, the (Abraham) Lincoln Batallion commander, screenwriter and future victim of Senator McCarthy’s House Committee on Un-American Activities, described Hemingway as “a cruel petty braggart… who wants to be a martyr”. Such self-mythologising was obviously not the desire of the majority, wherever they came from. Many merely shared a taste for excitement and a commitment to -democracy and the labour movement. Many did not realise how bloody the carnival would be. A Swiss anarchist swimmer was attracted by “the revolutionary tone”. Felicia Browne, a Slade School graduate, sought “artistic inspiration”: she died from bullet wounds while trying to help an Italian comrade. Two members of the east London Clarion Cycling Club cycled to war with the motto “nothing to lose but our chains”.

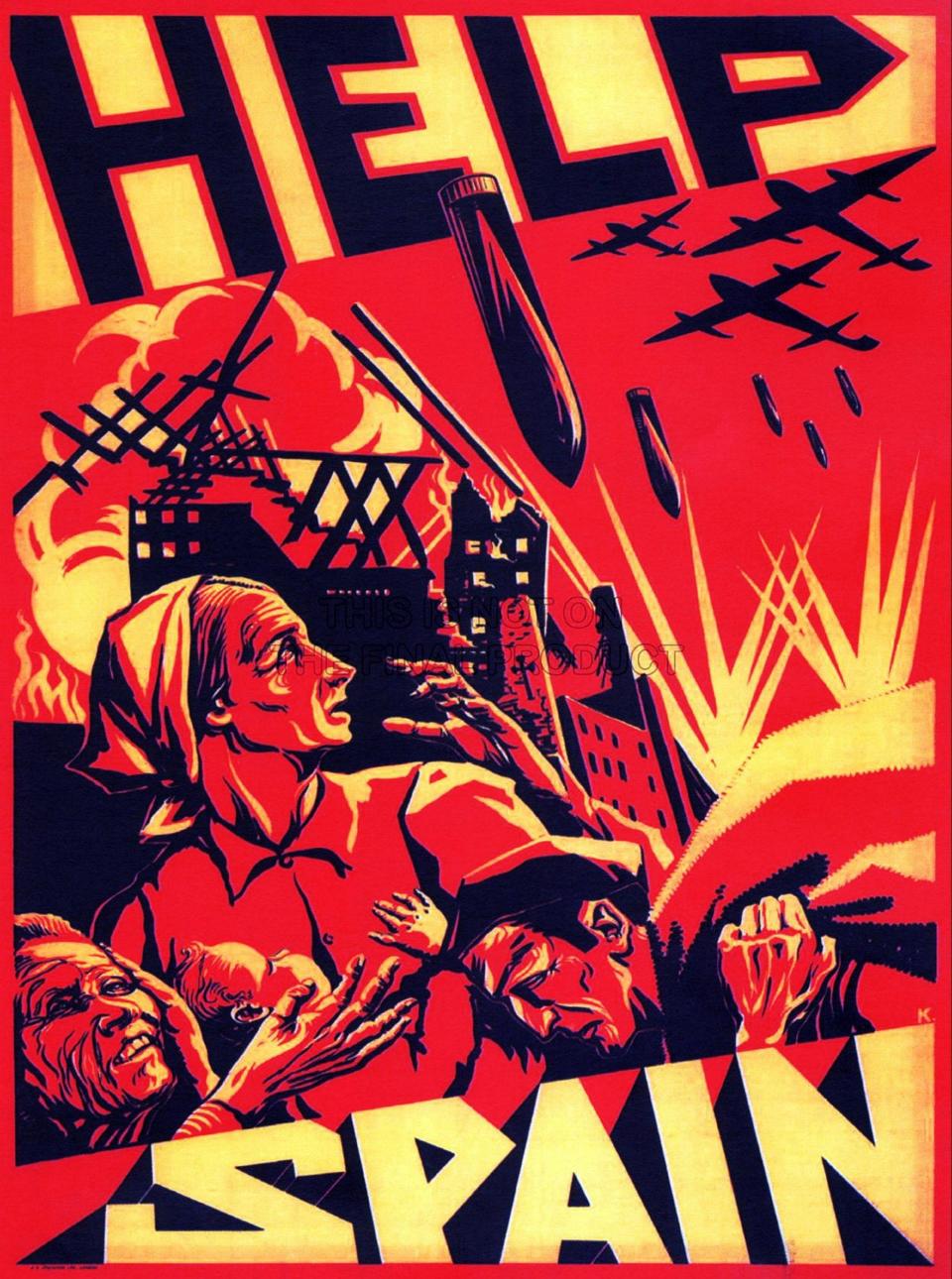

Tremlett describes how early volunteers from dozens of countries, some who had never before been abroad, understood the danger to Spain and were already gathering to defend the country while the ineffectual Republican government of Casares Quiroga did nothing, refusing to acknowledge the gravity of the situation, dismissing the coup as “guaranteed” to fail, even though northern towns were already falling to the rebels. And that indeed might have been the case had Hitler and Mussolini not intervened to -airlift Franco’s Army of Africa to Andalusia at the end of July and beginning of August 1936.

It was during those few crucial days that Stanley Baldwin and Anthony Eden, who like most men of their social class dreaded -communism more than fascism, pressured French prime minister Léon Blum to sign a declaration of non-intervention, a rehearsal for appeasement: more than 20 countries followed, effectively sealing the Republicans’ fate before the fighting had begun in earnest. The efforts of the French air minister Pierre Cot, who sold the Republicans aircraft on the sly, were in vain. Germany’s and Italy’s protestations of non-intervention were, of course, mendacious. Without them, Franco would have been defeated and democracy sustained. As it was, the Axis powers went unrewarded. When war broke out in the rest of Europe, there would be no quid pro quo. Franco had played them, skilfully and ungratefully.

Tremlett has accomplished a -tremendous feat of digging. He professes no stridently didactic intention, but he implicitly suggests that what happened in Spain more than three quarters of a century ago is not confined to those two years of squalor, risk and intermittent feats of bravery by modest people in pursuit of justice. It’s telling that the senile cretin Ronald Reagan announced that the Brigade’s Lincoln Batallion fought “on the wrong side”. That is, the side which lost.

There is a lesson here. We are reminded that even the most pitiful prentice politician covertly admires dictators because they are successful in accruing power for power’s sake. They are the ones whom the most unscrupulous and morally bereft emulate, they are the ones whom we must watch like hawks, to whom we must give a helping hand to send them on their way before they become fully self-crowned tyrants.

The International Brigades is published by Bloomsbury at £30. To order your copy for £25 call 0844 871 1514? or visit the Telegraph Bookshop