Inside the murder that brought down NYC City Hall

It was 11:30 p.m. and Vivian Gordon was heading out for the night.

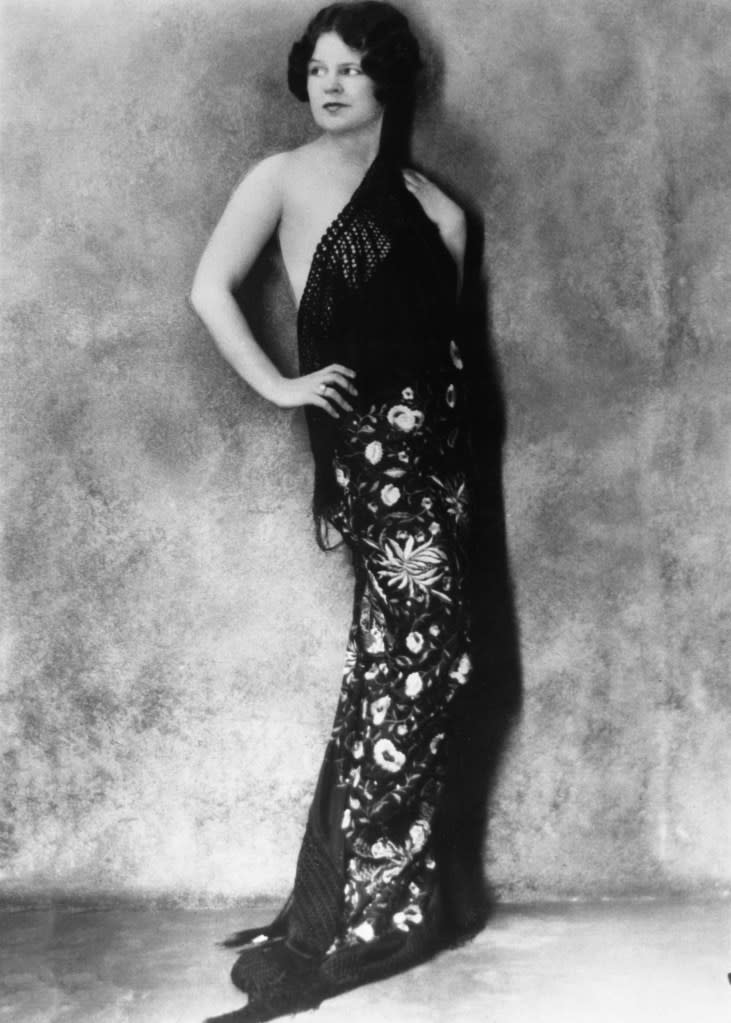

The flame-haired beauty wore a black velvet dress and mink coat, along with her usual array ray of diamonds.

She claimed she was an artist, and the staff in the East 37th Street apartment building where she lived noted her late hours.

She often didn’t come home till after dawn.

But that evening, Feb. 25, 1931, Gordon never returned.

Her dead body was found dumped in the Bronx’s Van Cortlandt Park the next morning.

A dirty clothesline encircled her neck.

Her face was bruised; her dress, torn.

Someone had stripped her of her fur and jewels.

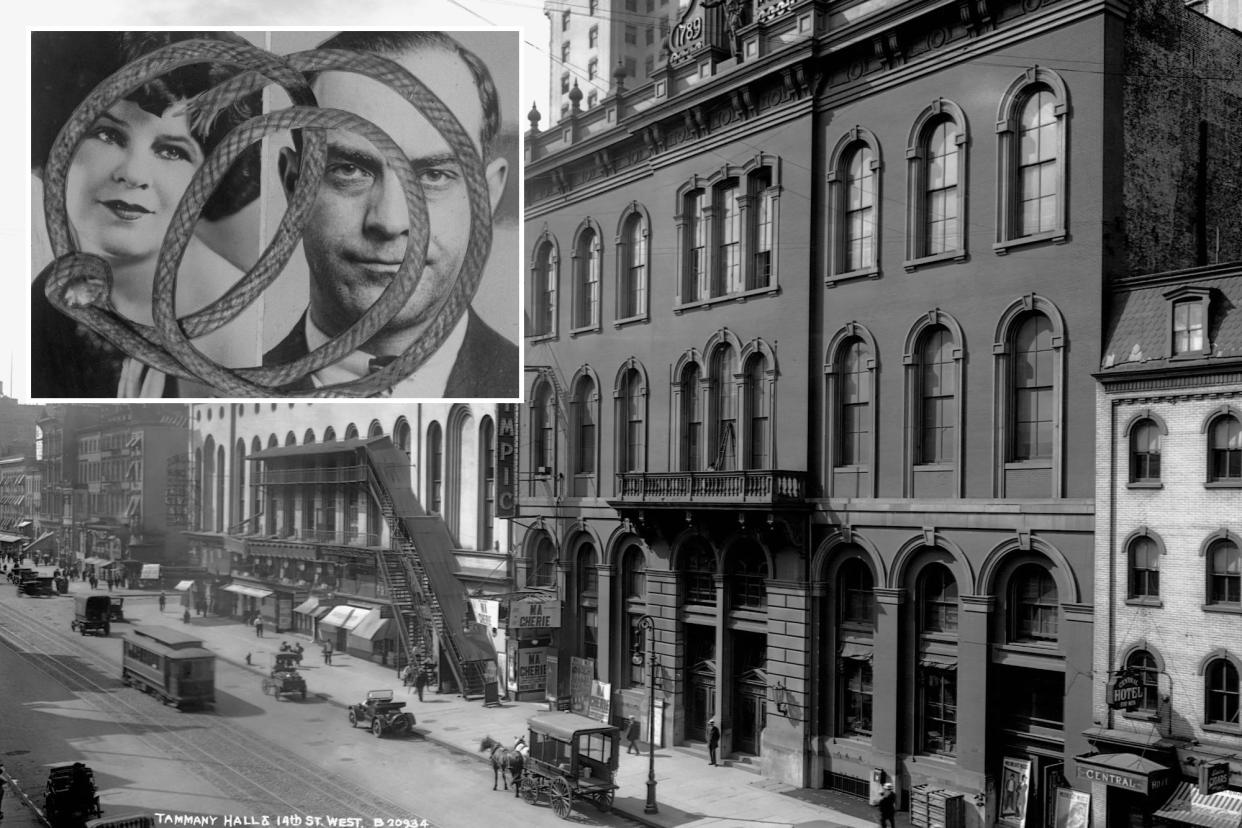

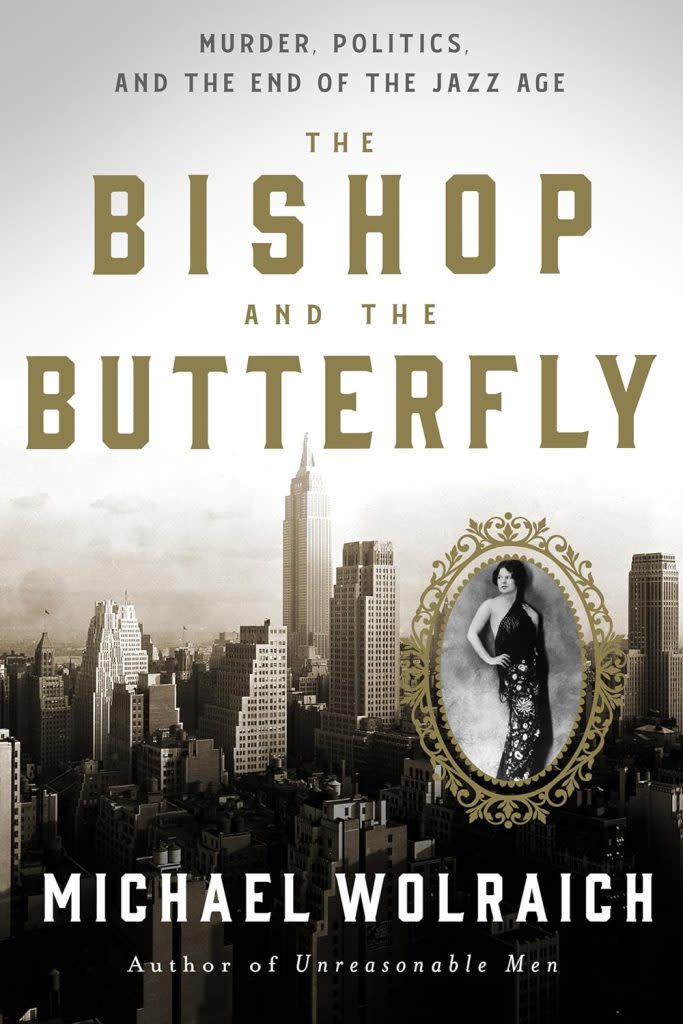

The grisly killing sent shock waves beyond the five boroughs, writes Michael Wolraich in “The Bishop and the Butterfly: Murder, Politics, and the End of the Jazz Age” (Union Square & Co., out Feb. 6), a new book about this sensational — and consequential — crime.

It turned out Gordon, the “Broadway Butterfly,” wasn’t your typical Jazz Age party girl.

When detectives searched her apartment, they found notebooks filled with the names of prominent businessmen, politicians and gangsters.

They discovered a diary detailing extortion plots and gold-digging schemes.

And amid all this, they uncovered a letter from an anti-corruption commission established by New York Governor Franklin Delano Roosevelt.

That commission — led by Judge Samuel Seabury, known as “the bishop” for his unimpeachable morality — had recently exposed a conspiracy between Manhattan police and prosecutors to frame innocent women as prostitutes.

Gordon had met with the commission five days before her death.

Was Gordon one of these framed women?

What did she know?

And had she been executed in an attempt to shut her up?

Gordon is now largely forgotten, Wolraich writes, or at most reduced to a titillating tabloid tale.

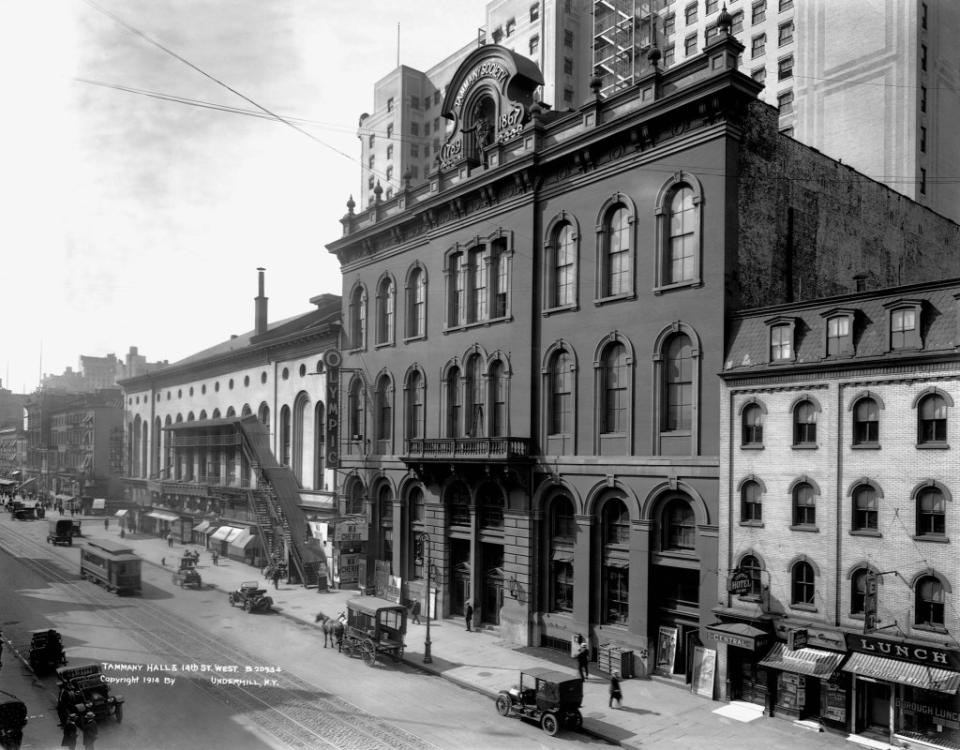

But he argues that the ramifications of her murder changed Gotham forever, bringing down both its corrupt mayor and Tammany Hall, the political machine that had ruled the city for a century.

“Her spirit is woven into the history of her adopted city, one small forgotten thread in the glorious tapestry of New York City,” he writes.

Vivian Gordon — then named Benita Bischoff — arrived in New York City in 1921.

A former vaudeville actress, she had ditched her touring career to become a housewife in Philadelphia. Yet, she missed the theater.

So the 29-year-old rounded up her 7-year-old daughter and left her husband for the bright lights of Broadway.

Two years later, a crooked vice cop named Andrew McLaughlin picked her up for prostitution.

In one version of the story, the plainclothes officer claimed to be the roommate of an acquaintance and then arrested Gordon when he let her into his apartment.

In another he picked her up on the street and gave her $20 out of kindness.

He arrested her, she said, because she took what she thought was a charitable gift.

But McLaughlin was actually part of a “shakedown scheme” between the police and prosecutors.

The judge who ruled these cases always accepted the cops’ testimony.

So, if the accused paid a bribe, the police would skip the hearing, and the case would be dismissed.

“Otherwise, the officer would testify, and the suspect would invariably be convicted,” writes Wolraich.

Gordon didn’t have money to pay bail, and her lawyer suggested she plead guilty to soliciting a cop in order to get a reduced sentence.

Instead, the judge sent her to Bedford, a notorious women’s reformatory.

That decision, writes Wolraich, “depriv[ed] her of her young daughter and destroy[ed] her reputation, consigning her to a life of crime.”

“You can’t imagine what I learned at Bedford,” Gordon later wrote to her sister.

The other inmates “showed me and told me how to do everything in the underworld.”

When she was released 2.5 years later, she became an actual prostitute.

Yet Gordon — smart, artistic and with a sparkling wit — had more finesse than your average lady of the night.

She could reel in the big spenders.

Soon, she had her own gold-digging schemes, seducing and then blackmailing (usually married) rich men, extracting expensive gifts and large sums of cash from them.

She also ran an escort service, had several rental properties and collaborated with the city’s most notorious madams, bootleggers, mobsters, and crooked lawyers.

When money was tight, she wasn’t above turning the occasional trick with wealthy drunk men for a quick buck.

Yet she was desperately unhappy.

She frequently feared for her life.

She seethed at her wrongful conviction, convinced that it was a scheme set up by her husband to retain custody of little Benita.

Then she read about Seabury’s commission investigating the city’s magistrates and the prostitution racket that he uncovered.

And she decided to speak up.

When Franklin Delano Roosevelt read about Gordon’s killing in the papers, and her tie to the Seabury commission, he immediately took action.

The New York governor didn’t normally get involved in homicide cases, but he saw how the story could have political consequences beyond the state.

Roosevelt wanted to be president.

But New York City was a cesspool of corruption and crime, which had “exploded” during Prohibition and looked especially bad during the Great Depression.

“The scandals and murders had tarnished FDR’s reputation for effective leadership,” Wolraich explains. “A sensational news story about the murder of a beautiful extortionist threatened to draw more national attention to the city’s broken justice system, which would be especially damaging if the police turned out to be responsible for her death.”

Roosevelt had already asked Seabury to investigate the city’s judges for corruption and graft.

Now as he pressed the police to find Gordon’s killer, he expanded Seabury’s inquiry to include the Manhattan D.A., the entire police force and the top of New York’s political machine, Tammany Hall.

Seabury found a link between police and illegal gambling rings (with many big games played in Tammany’s clubhouses).

One Tammany boss in Queens sold New York Supreme Court nominations.

Bribes were rampant.

Particularly galling in a time when so many New Yorkers were suffering during the Great Depression, the commission found that Tammany leaders had diverted millions of unemployment relief to “loyalists.”

The flagrant corruption led to New York City’s mayor Jimmy Walker to resign in disgrace.

In 1933, New York elected a Republican mayor, Fiorello La Guardia, who served three terms and cleared out much of the rot leftover from the Walker administration.

Tammany Hall grew weaker; Seabury retired in glory — FDR became president in 1933.

As for Gordon — her story does not have a satisfying end, writes Wolraich.

She was not a proto-feminist hustler who used her beauty and brains to outsmart rich, dumb men.

By the time she was killed, she was broke and desperate.

Her murder wasn’t a police cover up.

It was likely something more personal, hastily planned by one of her lovers and business associates and executed by two violent henchmen, who couldn’t even pawn off her fur coat and diamond ring.

Yet, Wolraich points out, “the popular outrage unleashed by her murder” changed New York City, and the country, for the better.

“Vivian Gordon did exact vengeance in the end, not on one or two men but on the entire institution that had destroyed her life and so many others.”