Independent stations fear they face a death knell in David v Goliath battle

When the BBC announced plans earlier this month to launch a new Radio 2 spin-off station focusing on music from the 1950s, ‘60s and ‘70s, it promised a “distinctive take on pop nostalgia”.

The as yet unnamed station would, the corporation said, “curate the story of pop music from these eras by some of the people who shaped the cultural landscape at the time”.

The new venture – one of four proposed spin-offs, would, moreover, “provide a soundtrack unmatched by anything in the current marketplace”.

One senior figure in the wider radio industry says the BBC has the “bit between its teeth” with the heft to “steamroller the opposition”.

Critics of the plans say the BBC used to have a station – quite a successful one – that did a lot of what is now proposed by the spin-off. It was called Radio 2.

And after Radio 2 arguably “abandoned” its older listenership by pivoting towards a younger audience from about 2018, commercial radio stepped in with a plethora of innovation to serve those Baby Boomers.

Numbers grew, while at the BBC they declined (only 6 Music increased its audience last year).

For the state-funded monolith now to seek to muscle its way back in, at a precarious time financially for these enterprises, is flat-out unfair, commercial radio leaders are saying.

New station to focus on calming classical music

They are therefore gearing up for what they see as a David vs Goliath battle to get it stopped.

Alongside the Radio 2 spin-off, a proposed Radio 1 extension would focus on music from the 2000s and 2010s, while Radio 3 will also get a new station to focus on calming classical music.

The existing Radio 1 Dance station, currently only available online, would also be launched on DAB+ with extra content.

These would be the first new stations to be launched on the BBC DAB network since 2002.

“Arrogant”, “panicked” and “effing cheek” were just some of the words chosen by Phil Riley when he spoke to The Telegraph this week.

A doyen of commercial radio, four years ago Mr Riley was gliding towards a well-earned retirement after more than 40 years in the industry, with the launch of Heart FM radio in 1994 among his many successes.

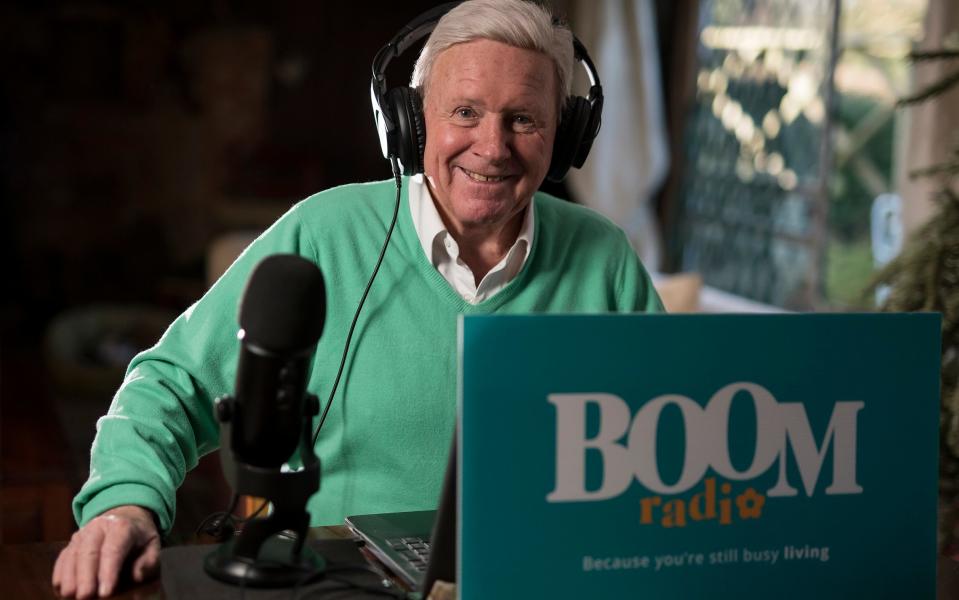

But, aware of the growing number of “homeless” older listeners, he and business partner David Lloyd dug deep into their pensions, put their reputations on the line and in 2021 launched Boom Radio, a station explicitly aimed at the 1946 to 1964 generation.

With no central studio, veteran presenters such as David Hamiton and Nicky Horne began presenting from their gardens sheds.

Boom now has more than 627,000 listeners a week, with the average listening time at 11 hours a week, higher than Radio 2’s 10.2 hours.

Eighty per cent of these listeners are aged 55 or over, the exact target of the new Radio 2 service, according to the BBC’s consultation document.

“The commercial market essentially said [to the BBC] ‘“Well if you’re going to abandon these people, we’re going to serve them’,” said Mr Riley, 64.

“The arrogance of the BBC saying six years later, ‘Maybe we made a mistake, maybe we ought to go back and serve them again’, it makes my blood boil.”

In simple terms, with the BBC’s inbuilt advantages of licence fee funding and formidable power to market its new products across existing platforms, a new Radio 2 spin-off could quite plausibly crush the likes of Boom and similar commercial stations.

“When the BBC gets the bit between its teeth it can steamroller the opposition,” said Mr Riley.

“We’ve seen it on multiple occasions over the years, both on TV and radio.”

“It’s typical. They wait until someone else has a good idea and then they say ‘Well that’s a good idea, we’ll do it’.”

Mr Riley candidly admits that, while things are going well at Boom, they need to roughly double their listener numbers to truly be considered a commercial success.

It is why the proposed entry of the BBC into their part of the market at such a fledgling moment leaves such a bitter taste in the mouth.

Their great hope is Ofcom.

To launch on DAB+, the BBC must convince the regulator that its new stations are in the public interest.

With a formal letter this week, Mr Riley and others are making the case as strongly as they can that it is not.

“The balance just isn’t there,” he said. “There is no public benefit to this radio station whatsoever and there is clearly going to be significant damage to commercial competitors and in particular to Boom Radio.

“We’re going to fight this proposal tooth and nail.”

The formal process is not likely to start for at least six weeks, while a consultation runs.

However, executives at Boom fear the corporation may try to present Ofcom with a fait accompli by launching the new stations online first via BBC Sounds.

Radio 1 Dance is, after all, already broadcasting online.

When asked by The Telegraph, on Friday, the BBC did not rule this out.

Instead, it said it would conduct a “materiality assessment” which would involve engagement with commercial players

If the BBC does launch online, it could be hugely damaging to their commercial competitors – in the case of Boom Radio, 54 per cent of listeners currently tune in over the internet.

Mr Riley describes this as an “immediate threat” and has explicitly asked Ofcom to prevent it.

For its part the BBC is adamant that its proposed Radio 2 spin-off would provide a distinctive offering, not least because of the extensive archive of concerts and sessions to which it would have access.

The mix would include some existing Radio 2 content, such as Sounds of the 60s and The Paul Gambaccini Collection, alongside “bespoke commissions”.

According to the consultation document, the station would “draw on a library of 5,000 tracks a year”.

All of which raises the obvious question in the BBC’s favour: isn’t more listener choice better than less?

Mr Riley is unimpressed, however, pointing out that 5,000 tracks is not “some miraculous number”, and “every radio station in the world plays Elton John”.

He said: “At Boom we’ve played 10,000 separate pieces of music over the last three months.

“We know they love listening to Whiter Shade of Pale by Procol Harum or Good Vibrations by the Beach Boys. Of course they do.

“But we play a huge repertoire of other material: secondary hits, album tracks, things that got away. And our listeners love hearing those.

“But if you’re up against someone playing far fewer tracks than that, which by the sound of it the BBC spin-off would be, you run the risk that every time you play something a bit left-field they go ‘I wonder what the BBC service is playing’ and suddenly they’re off.”

More broadly, the BBC hotly contests the charge that Radio 2 has abandoned its older listeners, a spokesman saying that it had always been aimed at audiences over 35 and that the station currently has seven million over-55 listeners.

However, it is hard to dispute that for some years now the station appears to have been prioritising a younger audience, specifically those 35 to 44-year-old “mood mums”.

The roster of presenters, critics argue, is ample evidence of that, with the departures of the likes of Ken Bruce, Simon Mayo, both of whom have now found themselves at commercial rival Greatest Hits Radio, which added 2.8 million listeners last year.

Meanwhile, Radio 2 lost about a million listeners last year.

Mr Riley said: “I’ve been in commercial radio for 45 years and for most of that time we’ve been behind the BBC.

They’ve been rattled by that

“But recently we’ve been ahead, because in the past 10 years we’ve relentlessly innovated, online and on DAB – country stations, ethnic minority stations, specialist music stations, you name it.

“They’ve been rattled by that.”

Then there is the question of money.

The BBC estimates that its four new proposed stations will cost £3.09 million a year, including music rights, with the Radio 2 extension comprising £420,000 of that, or £35,000 a month.

Mr Riley said this was “fanciful”, pointing out that Boom currently operates off £35,000 a month, despite their veteran presenters being “not well paid” and mainly “operating from their garden sheds”.

He accused the BBC of “hiding” the true costs in other budgets, arguing that the real expense of just one new spin-off station would be at least £3 million, when you take into account the increased music rights the BBC would be likely to have to pay given the extra listeners, plus other factors.

The BBC said in response that it had set out the budget “clearly and transparently” and repeated that the new stations would be “good value” for the licence fee payer.

The issue of cost is particularly sensitive in the light of significant cuts to BBC local radio output in recent years, although the corporation emphasised that the overall budgets for BBC local services had not been cut.

A spokesman for Ofcom said: “We are aware of the BBC’s plans to make changes to its audio services. At this early stage, it’s for the BBC to consider the impact of these changes on competition, and we expect it to engage with industry stakeholders as part of this process.

“In addition, we have extensive powers to thoroughly scrutinise the BBC’s plans once they are further developed. This will also involve listening to the views of interest or affected parties.”