Hollywood’s blackmailer-in-chief: the dirty cop behind Confidential, the tabloid the stars feared

“Being a private detective is a dirty job. There is no two ways about it,” Fred Otash admitted at the peak of his reign as Hollywood’s most notorious, sleazy private investigator. The former vice cop worked for anyone who paid him: The White House, the mafia, film studios, politicians and gossip magazines. He drew the line only at working for “communists”.

James Ellroy, author of L.A. Confidential, has featured Otash as a fictional character in four books, including his newly-released novel Widespread Panic. For nearly a decade, the best-selling crime author, along with director David Fincher, has been trying to get an HBO series about Otash, called Shakedown, off the ground.

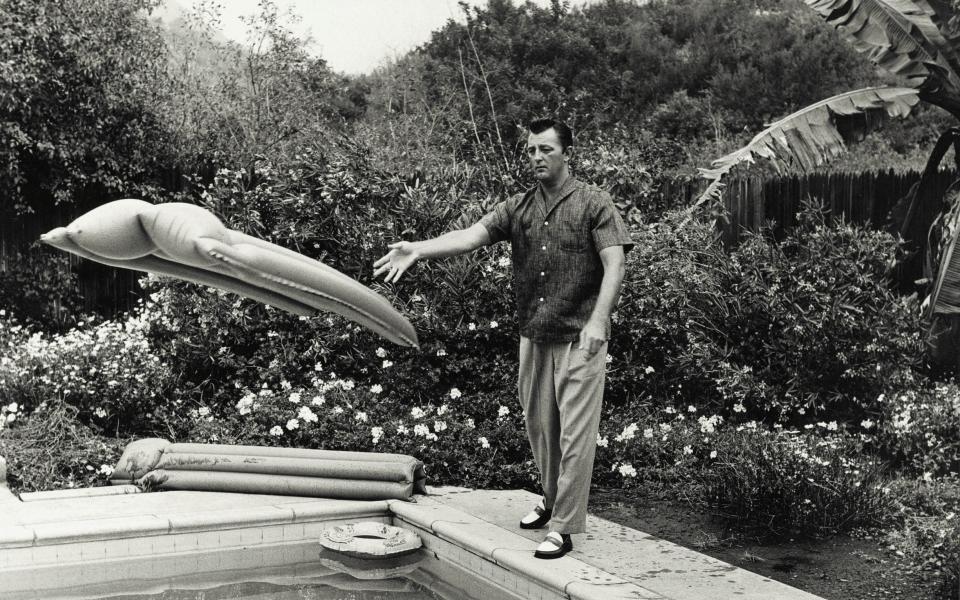

Otash’s resumé reads like a who’s (slept with) who of the 20th-century movie world and he was up to all sorts of dirty tricks in cases involving Marilyn Monroe, Barbara Payton, Bob Hope, Rock Hudson, James Dean, Bette Davis, Judy Garland, Robert Mitchum, Edward G. Robinson and Lana Turner, among many others. Ellroy, whose new novel imagines Otash in purgatory, confessing his sins, described him as “the hellhound who held Hollywood captive”.

Otash, the youngest of six children of Lebanese immigrants Habib Otash and Marian Jabour, was born on January 6 1922 in Methuen, Massachusetts. After being thrown out of high school for fighting, he worked as a lifeguard at the Miami Biltmore Hotel, before enlisting in the Marine Corps in 1942. “I did intelligence work for the marines,” the burly, 6’ 2” soldier later admitted. After being discharged in 1945, he joined the Los Angeles Police Department, working first as a traffic cop and quickly moving to vice, where he worked for the following decade.

He soon became a well-known figure on Sunset Boulevard, catching drug dealers and sex offenders for the LAPD during the day and mixing with celebrities at the Hollywood Palladium at night. One of his regular details was arresting the sex workers who preyed on ex-servicemen, getting them drunk and “rolling them for their money”. He also worked at Santa Monica beach, “drilling holes in the men’s changing rooms” to arrest those he described offensively as the homophobic slur “f__”. The experience only deepened his morose view of human nature. “We caught plenty of priests, rabbis and politicians,” he told television interviewer Skip E. Lowe more than three decades later.

Otash quickly developed a sharp nose for celebrity scandal and soon became a “fixer” for top stars. He later bragged that he helped James Dean get off a charge for stealing caviar from a food shop, and managed to get a case against Eroll Flynn dropped after the star of Robin Hood was arrested for stealing an off duty policeman’s badge.

In 1950, on his 28th birthday, Otash married Doris Houck in Beverly Hills. She was a struggling actress, whose most recent film – 1947’s Brideless Groom, a comedy starring the Three Stooges – had done little for her career. The honeymoon period was soon over and their relationship was fractured by a paternity battle over Houck’s daughter, Colleen Gabrielle, who was six months old when they wed. Houck at first claimed that Colleen was fathered out of wedlock by her previous husband, an oil worker called Edward G Nealis. She then claimed that “she really didn’t know who was the baby’s father”. Although paternity was decided in favour of Otash, the relationship was permanently soured. They agreed to divorce after only nine months, by which time Houck was working as a clerk at an aircraft plant.

Although their first divorce petition was halted after they agreed to a reconciliation, it was not long before his philandering and appalling domestic violence caused a permanent split. In June 1952, under the headline ‘Vice Squad Officer’s Wife Given Divorce’, the Los Angeles Times reported on the tawdry revelations at the Santa Monica Superior Court. “She received an uncontested divorce on testimony that Otash struck her while she was pregnant,” the paper reported, adding that the blow caused her to suffer a miscarriage. Houck shocked the court with her testimony about Otash’s behaviour. “He gave me one day to get out of the house and told me he would not be responsible for his actions if I did not,” she said.

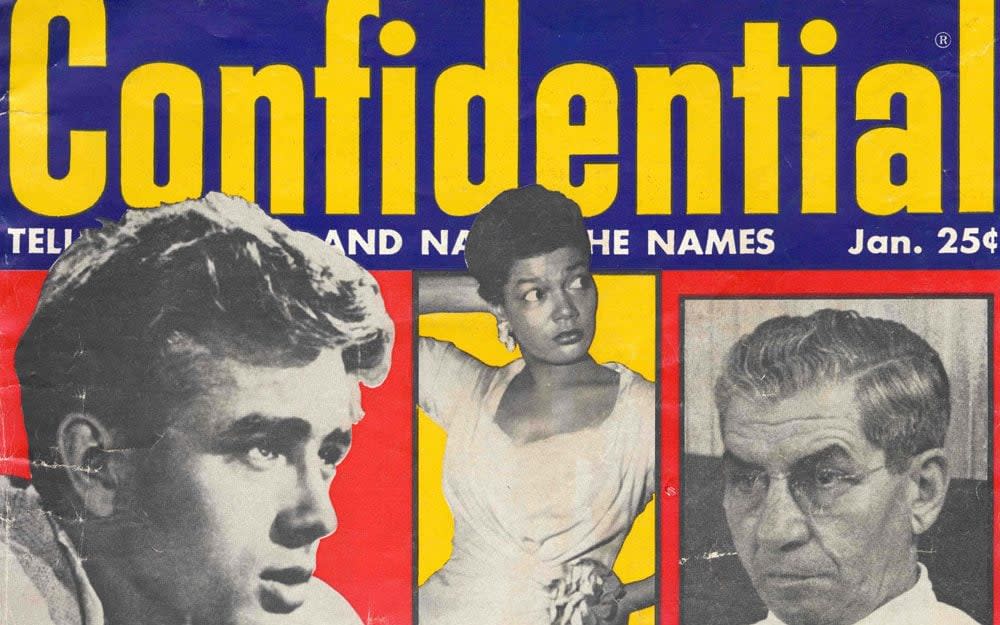

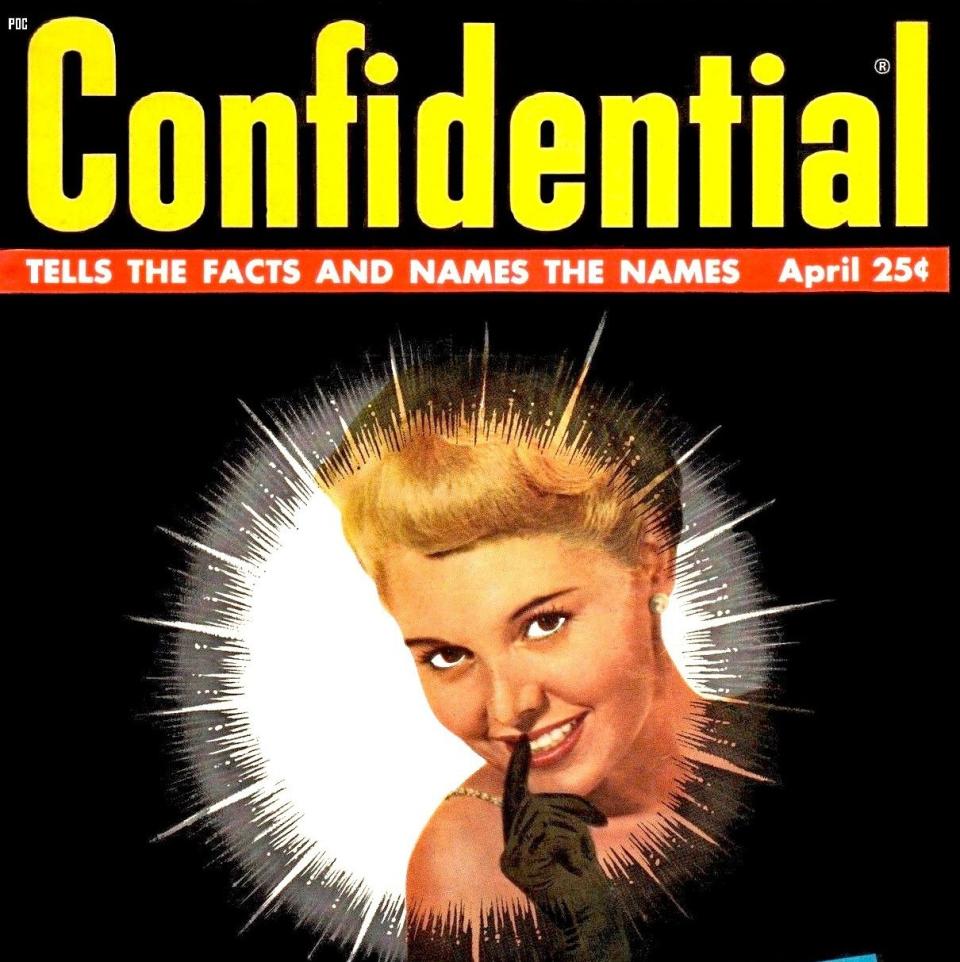

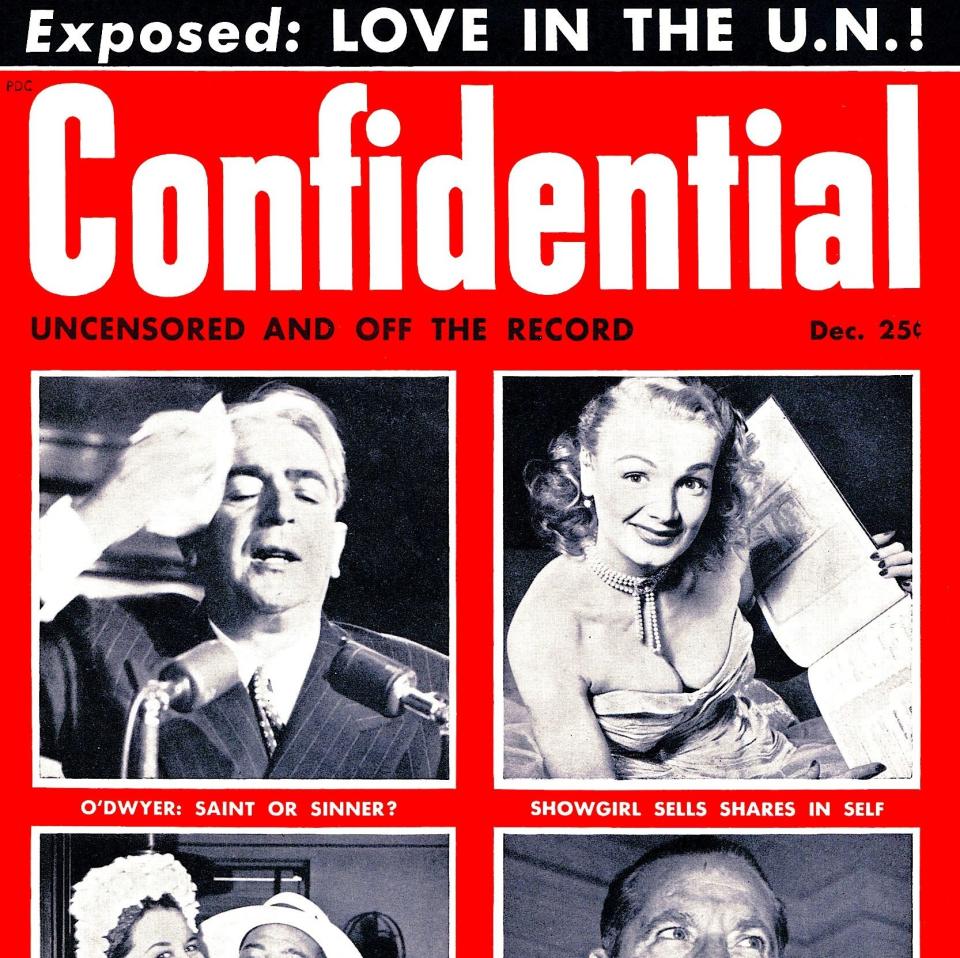

Luckily for Otash, the court case came before the launch of Confidential, a monthly magazine which started in December 1952. The publication, whose pursuit of scandalmongering was described as a “reign of terror”, thrived on revelations about Hollywood celebrities, and Otash knew he could feed their hunger for smut. Confidential became one of his primary sources of income after he left the police force in 1955 – following what was described as a “personality conflict” with LAPD Chief William H. Parker – along with the money he earned doing work for studio bosses such as Howard Hughes, and top Hollywood attorneys such as Melvin Belli and Jerry Giesler.

Otash, a master at strong-arming witnesses, gathered evidence to help them defend clients. “I spent 10 years putting people in jail and the next 20 years keeping them out of jail,” he joked to Lowe.

Otash made few press appearances in this decade. He did one interview with prime time host Mike Wallace, who described him as the “most amoral” man he’d ever had on his show. Otash admitted to Wallace, in this 1957 interview, that he earned more than £100,000 a year (around $1m in today’s money) for his activities. When asked how he could “justify invading people’s privacy”, he replied unabashedly that “if you can see it or hear it, you are not invading any privacy.”

Wallace grilled Otash about his reputation for violence when he was a vice cop, specifically asking how he earned the nickname ‘Gestapo Otash’. “Well, I have batted a few heads,” replied the man known affectionately in the movie world as ‘Mr. O’. Otash later inspired Jack Nicholson’s hard-boiled private eye Jake Gittes in Chinatown. Screenwriter Robert Towne said he studied Otash’s detective work, especially his antics in marital dispute cases, admitting “I drew on him for the character” in Roman Polanski’s 1974 classic.

Wallace was not alone in taking a dislike to Otash. Over the years, Ellroy has described Otash, whom he met several times in Miami in the 1970s, as “a rogue cop,”, “a shakedown artist”, “a dips__”, a “c__sucker”, “a sack of s__”, “a con artist”, “a bulls__ter, and a man it was “impossible to trust”. Otash has been a character in The Cold Six Thousand, Blood’s a Rover, Shakedown and July 2021’s Widespread Panic – and Ellroy admits to a fascination with a man who spent much of his life making money by revealing people’s most intimate secrets, unconcerned by how many lives he wrecked in the process.

In an interview in June 2021 with the LA Times, Ellroy talked about Otash’s modus operandi. “He went out and greased all the bellmen, and he went in there and hot-wired specific rooms and suites at all the high-line LA hotels. He paid desk managers a retainer to steer cheating celebrities into those suites and rooms, which were bugged 24 hours a day. He was down in the nitty-gritty of that first decade of big-time bugging, wiretapping and electronic surveillance.”

After moving to America, fledgling actor and screenwriter Steve Hayes, who was born in Streatham, London, became the manager of Googie’s Coffee Shop on Sunset Boulevard. In 1955, he met Otash there and started working occasionally for Otash’s private investigation bureau. His tasks included taking surreptitious photographs of actress Anita Ekberg to “catch her screwing”. Otash sold them to Confidential. “I hated the job and as my writing progressed, I gave up PI work. I found it sleazy,” Hayes admitted.

Otash was well-rewarded by Confidential for any stories of adultery and he became a specialist at “outing” homosexual celebrities. Otash boasted about his exposé stories on pianist Liberace and actor Tab Hunter. He even did a “background check” on Ronald Reagan, who was an acquaintance. “I’ll work for anybody but communists. I’ll do anything short of murder,” he said. For many years, his work as an FBI informant meant the authorities ignored his activities.

Otash originally came to the attention of Hughes during his cop days, when he was paid in cash to help get a drugs charge against actor Robert Mitchum dropped. Although the ploy was unsuccessful, Otash remained a friend of the Mitchum family. Mitchum’s younger brother John, also an actor, once gave a memorable account of a visit to Otash’s luxury apartment in Beverly Hills, published in the 2001 book Robert Mitchum: Baby I Don’t Care, in which he described desks covered with recording and listening devices, and a room full of cameras with zoom lenses. It was clear that Otash, “a big, mean man”, was at the centre of a “quasi-blackmail” operation. “It was command central for Confidential’s fact-gathering and surveillance agents,” said John Mitchum. “The place was filled with big, tough looking guys, and some of them looked like they were packing heat.”

Otash himself always carried a gun strapped to his calf, driving around in a surveillance van that was disguised as a television repair truck. He knew almost every scrap of Hollywood gossip and became the go-to ‘fixer’ for the stars. Bette Davis hired him to snoop on her husband Gary Merrill, in full knowledge that his methods were dubious. An FBI file on Otash stated that he used “a seemingly inexhaustible list of call girls” to gather information, prowling Hollywood by night in a chauffeured Cadillac full of the women he called “his little sweeties”. He had sources who were higher-placed than sex workers, though, and later confessed that, during the 1950s, he was being fed information by people on his payroll within the FBI, CIA, LAPD and Department of Justice.

One of the most highly-publicised cases of the era was when a grand jury convened in Los Angeles in May 1957 for a libel and obscenity trial against Confidential. The magazine’s young Irish attorney Arthur Crowley instructed Otash to serve subpoenas on 117 stars – including Ava Gardner, Frank Sinatra, Gary Cooper and Elvis Presley – who had appeared in Confidential articles. The move prompted a rush of celebrities leaving America for a sudden vacation in Mexico, desperate to avoid becoming embroiled in what was dubbed “The Trial of a Hundred Stars”. Crowley quipped that “it looked like the Exodus from Egypt”.

Otash later admitted that he tipped off friends such as Sinatra, “that ballsy guy John Wayne” and Clark Gable. He let Gable “off the hook” by telling him the best time to “sneak out of his ranch”. The jury were unable to reach a verdict in the case, and Confidential later cut a deal with the studios agreeing that they would no longer “publish exposés of the private lives of movie stars”.

It may have been anxiety over lost income from Confidential that caused Otash to branch out in a risky direction the following year, when he became involved in horse racing crimes for mobsters eager to knobble horses owned by rivals. Otash was caught injecting depressant drugs into horses at Santa Anita racetrack. In 1959, UPI reported that a grand jury investigation found Otash guilty of bribing jockeys and conspiracy to dope horses. Otash called in favours, however, and his felony conviction was later downgraded to a misdemeanour and eventually expunged from his record. He got away with a suspended sentence. “I was in jail a couple of times but always got out the next day,” he joked to Lowe.

Eager to drum up new business, he ran promotions for the Fred Otash Detective Bureau in local newspapers. His marketing did not go without hiccups. The adverts printed in November 1960 were full of typos (his surname was spelled ‘Ostash’ and the copy suggested choosing your ‘investor’ carefully, when it should have said ‘investigator’). He also got in trouble with additional ads after adding bogus recommendations from the FBI and the United Nations. He was ditched by the FBI as an informant and, in 1965, had his licence revoked by California's Bureau of Private Investigators.

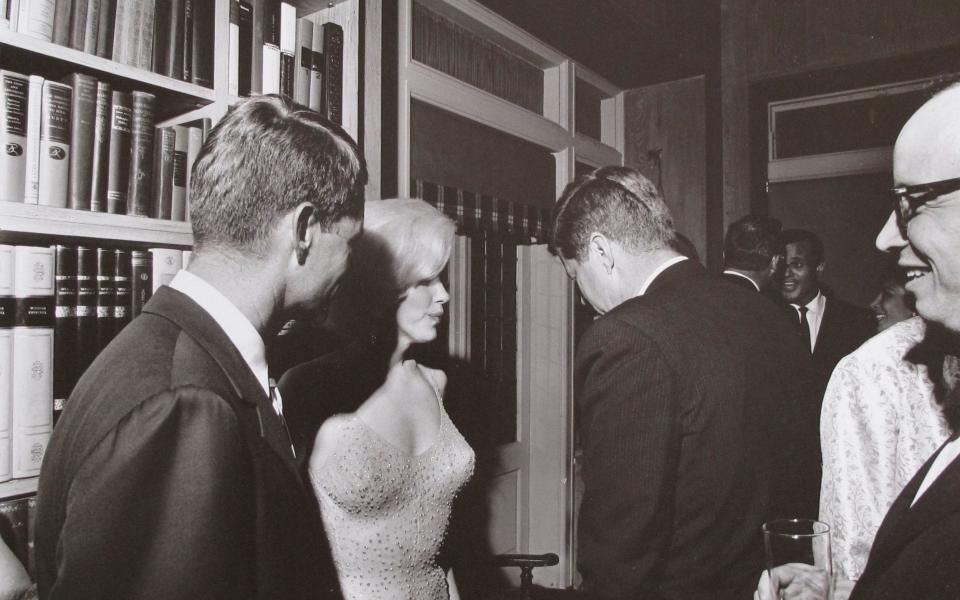

His most notorious activities in this era centre on his skulduggery with Marilyn Monroe and President John F. Kennedy – and it’s here, if that’s even possible, that the Fred Otash story becomes even murkier and more complicated. Otash later claimed that, around 1961, he was hired by mafia bosses to “dig up information on Kennedy”, reporting back on any rendezvous the politician had with women. He bugged houses Kennedy visited for liaisons and gained access to the most intimate scenes, later telling Ellroy that Kennedy was a “two-minute man”, who was “hung like a cashew”.

Otash often said that he knew all the true stories from “the greatest time in Hollywood history” and there is no doubt he was fond of spreading rumours. In Widespread Panic, Ellroy includes a scene in which Otash dishes the dirt on dozens of stars, including Natalie Wood, Johnny Weissmuller and Burt Lancaster, whom Ellroy’s fictional private eye calls “a sadist with a well-appointed torture den in West Hollywood. Pays call girls top dollar to inflict pain on them”.

Otash claimed he was bugging Monroe from 1961 and he gave numerous conflicting accounts of her mysterious death. In one interview he insisted it was “an accident”, in another he claimed, “I know for a fact that she committed suicide. She felt she was passed around and used and having nothing left to live for”. In 1985, he told the LA Times that on August 5 1962, the night of the actress’s death, he had been hurriedly hired by actor Peter Lawford, to “do anything to remove anything incriminating” from the death scene that linked Monroe to Lawford’s brothers-in-law, President Kennedy and Senator Robert Kennedy, both of whom allegedly had affairs with Monroe.

A year later Otash played 11 hours of tapes to writer Raymond Strait – the man who had ghosted Otash’s 1976 autobiography Investigation Hollywood: Memoirs Of Hollywood's Top Private Detective – that were supposedly recorded during and after Monroe’s death. In the book Marilyn Monroe: A Case for Murder, Strait told author Jay Margolis that “Fred was afraid of the tapes” because they included evidence of a row with Robert Kennedy and a disturbing altercation hours later with two other men, moments before she died. “It was horrible,” Strait later told television host Joan Rivers. “After hearing those tapes, there’s no doubt in my mind that Marilyn was murdered.”

In June 2013, 21 years after Otash’s death, it emerged that the former private detective had kept 11 boxes of secret files in a storage unit in the San Fernando Valley. His daughter Colleen, “aggrieved” by what she called Ellroy’s “insulting” portrayal of her father in his novella Shakedown, decided to counter this “horrible fictional depiction” of Otash by making public the notes he left her, one of which claimed he’d been conducting surveillance of Monroe on the day she died. “I listened to Marilyn Monroe die,” he alleged.

The audiotapes and transcripts, including those in which Otash claims “I did hear a tape of Jack Kennedy f___ Monroe”, have never been publicly released. Matt Belloni, chief executive of the Hollywood Reporter, later told CNN that the files his journalist reviewed, “contain elements that are not 100 per cent verifiable… they are his recollections to his daughter. So what he said and what is actual truth is not necessarily the same.”

Colleen, who was listed as General Partner/Manager of Fred Otash Productions in Redondo Beach, California, also released other surveillance tapes made by her father which revealed more of his nefarious dealings. They included accounts of how he covered up an “emotionally disturbed” Judy Garland’s drug use, and they also featured recordings made in January 1958 in which Rock Hudson’s wife Phyllis confronted her husband about whether he was gay.

Hudson was caught admitting “physical” relationships with young men. At the time, the tape would have created a sensation – his homosexuality wasn’t public news until 1985, when he issued a press statement announcing he had AIDS – and instead of making it public, Otash played it privately to Columbia Studios president Harry Cohn, who reportedly agreed to become an informant in return for Confidential suppressing the information.

This was a common tactic for Otash, and it’s no surprise that he was known as Hollywood’s “blackmailer-in-chief”. He didn’t care and would usually reply “alimony is just legal blackmail” to anyone who questioned his morals. Asked late in life whether he had any regrets, he said the only thing he would have done differently in life would have been to “study law”.

The 1970s were perhaps the quietest time for Otash, who moved to Miami at one point to work as head of security for the cosmetics company, Hazel Bishop, Inc, and its subsidiary, Lilly Dache. When the New York Times asked him about this job, he said he was happy to have no more involvement in investigating “adultery, child neglect, prostitution and those things.” His opinions on the Watergate Scandal were sought and he dismissed the amateurs who used a Xerox machine rather than camera equipment during their break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters in 1972. “I still can’t believe the Republican party could have hired such a bunch of idiots,” Otash said. “I’ve been on about 25 Watergates and never got caught. I’ve tapped about 600 phones in countries all over the world and never got caught.”

The lure of Hollywood proved strong, however, and in the late 1970s Otash made his way back to LA to take over the management of the Hollywood Palladium. In 1978, he tried to stage boxing events at the nightclub, but the city denied him permission. He continued to work as a freelance security consultant, later claiming that he was employed by Universal Pictures during the making of The Blues Brothers, helping them solve the problem of “John Belushi shoving coke up his nose” on set.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Otash did a few television interviews – Ellroy said “Fred was making a lot of ancillary dough… getting 7,500 bucks a pop to talk about JFK’s womanising, James Dean, the inner workings of Confidential” – and began working on a book called Marilyn, Kennedy and Me, which was supposedly optioned by Penguin. He spent about six months a year at his flat in Cannes, even though he said he disliked the French. “At the end of the war we should have let the Germans keep them,” he remarked. When not working on the draft of his book he said he loved nothing better than “checking out the topless and nude beaches”.

On October 4 1992, after returning to his West Hollywood home, he attended a Friars Club dinner to celebrate completing the first draft of Marilyn, the Kennedys and Me. He went home in the early hours, before suddenly calling for a taxi to take him to Los Angeles International Airport. When there was no answer at his apartment, the doorman, alerted by the driver, called Otash’s friend Manfred Westphal – a publicist who was Colleen’s business partner – who found the 70-year-old under the kitchen table, dead of a heart attack. Otash, who smoked four packets of cigarettes a day as an adult, and regularly consumed large quantities of bourbon, had been sickly for years with emphysema and high blood pressure.

Otash is buried at Hollywood Hills’ Forest Lawn Memorial Park in a plot called, appropriately, Murmuring Trees. Before he was even in the cold ground, and only two hours after his death, Otash’s executor, Crowley – the man he’d worked with on the famous Confidential trial 38 years previously – stripped the apartment of tapes and documents, removing the red filing cabinet that contained the former private detective’s most sensitive files. “He put a shackle on the door, emptied the condo, and nothing inside was ever seen again,” Westphal told the Hollywood Reporter. Crowley died in 2010 and with him, it seems, went some of the answers to Otash’s darkest secrets about Hollywood’s sleaze.